The public information films that scared Seventies children for life

From stranger danger to a mysterious Death-like spirit luring children into a lake, the public information films David Barnett grew up watching were brutal, terrifying and, sometimes, utterly perfect slices of filmmaking

I firmly believe I have made it to my mid-century years relatively unscathed because I have never thrown a frisbee near an electricity sub-station, or been enticed away by strangers, or played with farm threshing machinery, or – in my later years – absolutely never put a rug on a polished floor (because, as any fool knows, you might as well set a man-trap).

In short, I am here to talk to you today thanks to the public information films of the 1970s and 1980s which put the fear of God into me so much regarding hazards both obvious and hidden that navigating those chaotic decades of my youth became a much safer process.

Public information films – or PIFs to the aficionado – still exist today. We have seen them recently with regards to Covid; government advice on washing our hands, wearing masks and being careful of hugging our friends.

But next to the PIFs of the heyday of the genre, these touchy-feely, nicey-nicey televised messages are like comparing the Teletubbies with the Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

The PIFs of the 1970s, especially the ones aimed at kids, were absolutely brutal, terrifying and, in some cases, utterly perfect little slices of filmmaking.

In the 1960s up to the 1980s, the PIFs were produced by the Central Office of Information (COI), the UK government’s marketing and communications agency, which closed 10 years ago and its responsibilities transferred to the Cabinet Office.

The COI commissioned short, instructive films on a variety of subjects from independent filmmakers and studios, and they were provided free to the television networks to run as fillers, in ad slots for ITV and between programmes for the BBC.

The first PIFs date back to the Second World War, when the COI’s predecessor the Ministry of Information produced them to show in cinemas between the news reels and movie shows, often fronted by the actor and producer Richard Massingham. They ranged from “careless talk costs lives” type warnings to not unwittingly hamper the war effort, to salutary instructions to cover your face if you sneezed, all delivered in the plummy, Home Service tones later aped by Jon Glover as Miles Cholmondley-Warner in Harry Enfield’s Television Programme.

But two decades after the war ended it became apparent there was another war being fought – this time for the survival of our children who were on the front line of a never-ending battle with impending injury and death from often the most unlikely sources.

One of the most (relatively) gentle and best-loved series of PIFs were the six Charley Says animated shorts made in 1973 featuring a tousle-haired youth called Tony and his cat Charley, who spoke in caterwauling meows (voiced by the late, great Kenny Everett) which only Tony could understand. And it was a good job he could, because without Charley’s sage advice Tony would be hospitalised, captured by paedophiles, or just plain dead.

Charley would warn Tony not to play with matches, or not to go near a pan on the hob in the kitchen. In one frankly terrifying 60-second episode, Tony and Charley are playing on the swings when a very normal-looking man comes up and asks him if he wants to see some puppies. Excited Tony actually takes him by the hand and is going off to whatever horror awaits him. Fortunately, Charley is on full nonce-alert and warns Tony that Mum has said he should never talk to strangers. Tony relates this message to the man who scarpers, no doubt thinking that a kid who talks to his cat is probably too weird even for his depraved tastes.

The Seventies was a wasteland of discarded domestic appliances. It was positively apocalyptic out there. If you think fly-tipping is a problem today, 40-odd years ago any available patch of land looked like a Turner Prize art installation sponsored by Curry’s. And one 1971 film warned us of the dangers of climbing into one of the abandoned fridges that littered the landscape, where an unwary child could be trapped until the air ran out, with no one hearing their screams.

The thing about public information films was the fact that they’d pounce on us viewers without a moment’s warning

Another animated series featured Joe and Petunia, quite the stupidest couple in Britain. They would tramp through the countryside, leaving gates open and letting their dog chase sheep, or drive up mountains in their Mini without realising the tyres were worn down to the rims. One particularly surreal film has a rather lustful Joe wanting to go swimming in the sea because there’s a gorgeous mermaid in there. Petunia is less bothered about her husband’s obvious amorous intentions with the sea-going mythical creature than the fact there’s a “no swimming” sign present. They move along the beach to where it’s safe to swim, but Joe has changed his mind as the lifeguard has copped off with the mermaid. Quite what the message there is, I was never very sure. But I have certainly rarely followed a mermaid into dangerous waters, so there is that.

For decades the PIFs were relegated to nostalgia status for my generation, until the advent of the internet and YouTube in particular where they started to get another airing, leading to a DVD release of some of the best of them in 2001.

So we can all enjoy once again the sight of a child getting his legs severed by an express train because he failed to heed the warnings about playing on the railway lines, or the boy getting fried for trying to retrieve his frisbee from some power lines, or the freeze-frame horror of a small kid running along the beach and forever about to step on a discarded, broken bottle half-buried in the sand.

And then we have Apaches. At 26-minutes long, this 1977 film is the magnum opus of the PIF genre, directed by John Mackenzie, who was Ken Loach’s assistant director on Up the Junction and Cathy Come Home.

Apaches features six children who are playing a Wild West game on a farm. It’s tense, violent, horrifying and utterly brilliant. One by one the kids are picked off in truly horrific fashion by farming machinery and hazards that seems to be powered by some malevolent, supernatural driving force. One drowns in a slurry pit, one is crushed by a gate, one falls from a tractor. The film is even narrated by the last child to die.

It’s no wonder we were scarred for life by those films which, in no coincidence at all, is what Stephen Brotherstone and Dave Lawrence called the two volumes of their books that look at the pop culture from the 1970s and 1980s that did its level best to scare us kids witless. Obviously, PIFs make a major appearance in the Scarred for Life books.

“The thing about public information films was the fact that they’d pounce on us viewers without a moment’s warning,” rememberers Brotherstone. “Some of the genre’s prime examples would be aired during children’s television. There you were, watching Magpie or Michael Bentine’s Potty Time without a care in the world, and during the ad break you’d go from the sheer adrenaline of a Scalextric advert straight to the unrelenting horror of The Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water, the Bergman-esque hooded monk voiced by Donald Pleasence who hung around ponds and lakes and got off on watching kids drown. Or Edward Judd rolling up the sleeves of his beige jumper as he urged us to ‘Think once. Think twice. Think bike!’ accompanied by footage of the most hideously realistic bike crash (there’s a section of smashed brake light next to the biker’s head which was, in those days of blurry TV sets, often mistaken for a bit of his kidneys). This particular PIF was, of course, ripped to shreds by The Young Ones in 1984, but it still put me off motorcycling for life.”

Ah, yes, The Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water. Considered the absolute classic of the genre. We’ll have more of that in a moment, because it truly is for all intents and purposes a horror movie. Like all the PIFs, it was unrelenting and pulled no punches.

Brotherstone agrees: “There seemed to be no filters back then, no sense of how far was too far. The Central Office of Information farmed out these fillers to a group of jobbing filmmakers who seemed to have a more instinctive sense of pure horror than a room full of Hollywood directors. The aforementioned Lonely Water is a complete Hammer or Amicus film condensed into a minute and a half of pure terror. And it worked, too, helping to reduce the number of child deaths by drowning by a huge amount in the space of a year or so.”

What was evident about the PIFs was, despite the fact they were almost throwaway filler material, the care, professionalism and dedication to absolutely pushing the boundaries that the filmmakers employed.

“I genuinely believe that they represent the last great unexplored corner of British fil-making,” says Brotherstone. “No subject was too out there for the COI. From the obvious: don’t muck about with fireworks, don’t drink and drive, look both ways before you cross the road, don’t go with strangers, to the not-so-obvious: don’t run into huge panes of glass, watch out for Colorado beetles, don’t, erm, over-polish a floor (‘Put a rug on it, and you might as well set a man-trap’).

“And the effect they had on my generation can’t be overstated. Certain images, sounds, and tag-lines from ’70s and ’80s PIFs still resonate in our heads.

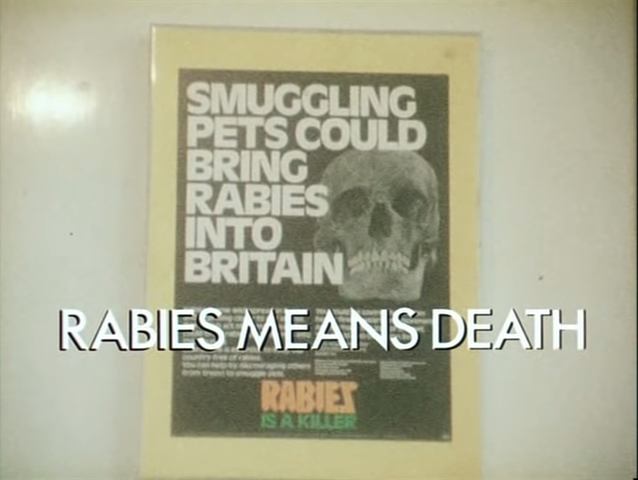

“And in case you’re still in any doubt as to their sheer power, there’s a certain rabies PIF, Rabies Means Death, which features genuine footage of a victim, spasming on a hospital bed in his death throes, which so traumatised me as a child that I still can’t watch it as a 51-year-old. And I’ve tried. When writing the PIF section for Scarred For Life Volume Two, I conceded defeat and handed Rabies Means Death over to my co-author, Dave Lawrence.”

So, The Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water. It was made in 1973, its role to convey the dangers of playing near water, and the device it employed was a hooded, Death-like figure which lurked, unseen, at rivers, points and flooded quarries, willing unwary and foolhardy children to acts of stupidity and bravado in the hope they would fall in and drown. Yes, the Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water wanted us dead, in the most horrible fashion. It fed on the drownings of children, haunting remote waterways, watching impassively as we played just inches from doom.

Lonely Water (to give it its official title, though it’s more widely known by the longer name) did indeed have British actor Donald Pleasence voicing the malign spirit, and was directed by Jeff Grant.

Grant had arrived in London in the late 1960s and entered the world of television, initially working for a number of advertising agencies.

In 1973 he was working at Illustra Films when the call came in from the COI with a commission for a PIF warning about the dangers of children drowning, following a spike in incidents over the previous year.

Grant, now 84 and living in South London, teamed up with writer and producer Christine Hermon for what would become Lonely Water.

I think you’ve got to be fairly tough on certain things, and tell the truth about things, and sometimes it feels we don’t do enough of that these days

He recalls: “Christine brought in this script she’d put together and said she’d had this idea of a monk-like figure. At the time I was obsessed with Ingmar Bergman, the Seventh Seal and all that, and I thought immediately of the guy with the hooded figure on the beach in that film.

“So I thought, yes, let’s go with that idea. I loved this script, it felt like something I could really get my teeth into. But it was quite a tough script, even for those days, and I wondered if we’d actually get away with it.”

Grant put together some ideas for visuals to marry up to Hermon’s script and she took it away to the COI who approved it. He says: “I was stunned, really, because we’d put quite a bit of tough stuff into it, like the bit where the spirit turns around and he’s got no face, but they just said yes.”

The film begins with a panning shot of a stagnant pond overhung with trees, and Pleasence intoning, “I am the Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water”, before the camera frames the ghostly figure, standing on the water (actually a platform 3mm below the surface), wreathed in mist. He is ready to trap the “unwary, the show-off, the fool”, and here’s one now, a boy trying to get a football from a flooded pit with a stick while his friends (among them Terry Sue Patt, who went on to play Benny in Grange Hill) egg him on. He falls with a splash and that’s the end of him.

The kids came from an acting school in Weybridge, but not a posh, middle-class one, says Grant. He’d used the school before because the children were down to earth and working class, and they perfectly fitted the bill for the procession of accidents that would feature in the film.

Elsewhere boy hangs over a pond on a rotten branch, the Spirit gleefully willing it to give way. Another child ignores a Danger, No Swimming sign, which only a fool would do… fortunately, opines the Spirit, there’s one born every minute.

One of the most fascinating devices Grant’s direction employs is scattering gravel pit with old cars, shopping trolleys and domestic appliances, representing the hidden dangers said to lurk in ponds and flooded quarries. And when the Spirit is eventually foiled by sensible children who he has no power over, he declares, “I’ll be back…”

The film was shot in two days, the opening shot at a lake about 20 miles north of London, the rest of it not far from Heathrow. Pleasence immediately agreed to do the voice over after seeing Hermon’s script, and the film was edited in a day, sent off to the COI, and within two weeks was on the air. Did Grant have any inkling that he was helping to birth a classic?

“I hadn’t a clue,“ says Grant. “The main reason for that is that I was so busy, going from one job to the next. And although it was a lovely and interesting job to shoot, and I enjoyed playing around with things in it, at the time it was just another film and after two days I’d moved on to something else and forgotten about it.”

Grant is currently working on his second novel – he published his first, Albatross, through Amazon five years ago – and although Lonely Water was just another job at the time, he’s been pleasantly surprised at the longevity of the short film, and the fact it’s picking up a whole new generation of fans in the internets age.

He says: “At the time there was never any official feedback so we never really knew what effect the films had, whether they actually helped. But people certainly seem to remember it, and I feel very privileged that something I did had such a long-lasting effect on people.”

Would such a hard-hitting PIF be made today? “I have no idea,” says Grant. “But I don’t think there’s anything wrong with driving a message home like that. I think you’ve got to be fairly tough on certain things, and tell the truth about things, and sometimes it feels we don’t do enough of that these days. Life isn’t all happy-clappy and kids are far more resilient that we think when it comes to messages like this, far more resilient than most adults, actually.

“I do feel very proud of Lonely Water, especially if it did help to save lives. With films like that, at least you do feel like you’re doing something useful, helping people, and not just selling someone cake mix or toilet paper.”

Though the heyday of the PIF was the Seventies through to the start of the Eighties, the convention as we know it really died in 1987, when the government released a series of films to warn against the dangers of Aids. Gone were the imaginative characters and striking imagery in favour of starkness and literally hammering the message home with no subtlety or finesse… a pair of hands chisel warnings to not die of ignorance into a monolithic tombstone.

The PIFs terrified us, but in a good way, an entertaining way, and their message was sound. The Aids films were apocalyptic and terrified everyone, not just their target audience. The classic PIF era was at an end.

To end on a higher note, I learned to swim because of PIFs, and specially because of one animated film, in which a cool dude called Dave (like me) who was replaced in the affections of a lissom blonde on the beach because he refused to get in the sea with her. A fairy godmother summoned up Phil, who swims like a fish, and gets the girl. A disgruntled Dave whistles up the fairy godmother, demanding, “I wish… I wish I didn’t keep losing me birds!”

The message to Dave is one for us all – and may just keep us safe from The Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water, should it ever make good on its threat to return. Learn to swim, young man. Learn to swim.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments