It’s not rocket science: The importance of psychology in space travel

With manned missions to Mars expected to take 2.5 years, small astronaut crews will face a truly unprecedented form of isolation. Len Williams learns how they’ll cope

Before I went to space, I made a cassette with 90 minutes of music from every continent on Earth,” recalls Reinhold Ewald, a German physicist who spent 20 days on the International Space Station in 1997. In the hour and a half it took him to complete his orbit, he would watch the planet pass below him and listen to its people’s music. This timeout was a perfect way to decompress from his high-pressure job, far from his family and normal hobbies.

Over the past year, all of us have experienced some form of isolation due to coronavirus restrictions and the mental health issues it can create. But while those of us locked down on Earth can at least get out the house for a change of scenery, space travellers have no escape from their cramped quarters.

Most astronauts today spend a few months at a time in space, with the longest continual sojourn being a 14-month mission undertaken by cosmonaut Valeri Polyakov in 1994-5. However, if humans travel to Mars, as space agencies plan in the coming decade, the time away from Earth will be much longer. A one way, 170 million-kilometre journey takes roughly six months. If astronauts land on the red planet and spend time there, a mission will likely last two and a half years.

“Imagine being stuck in a motorhome with five people for six months,” says Dr Jack Stuster, an anthropologist who has advised Nasa, “except there are no windows, and you can’t go outside.” On this analogous Mars voyage, “you know everything about the other travellers, having trained with them for years. You know all their jokes, their family history, their annoying mannerisms. When you get to your destination, you will spend most of the next 18 months in a slightly larger habitat together, before facing another six-month journey home.”

The psychological strains of such intense and long-lasting isolation are easy to imagine. How much of a problem are they, and how do space agencies prepare their staff for the inevitable stresses that will occur on such missions?

Ever since people have thought about travelling to other celestial bodies, the psychological issues have been discussed too. In a 1954 article on the challenges of a voyage to Mars, engineer Wernher von Braun asked: “Can a man retain his sanity while cooped up with many other men in a crowded area, perhaps twice the length of your living room, for more than 30 months? Little mannerisms – the way a man cracks his knuckles, blows his nose, the way he grins, talks, or gestures – create tension and hatred which could lead to murder.”

In the early days of space flight, psychological preparation was more of an afterthought. But over the decades space agencies have come to see psychological and behavioural preparation as vital.

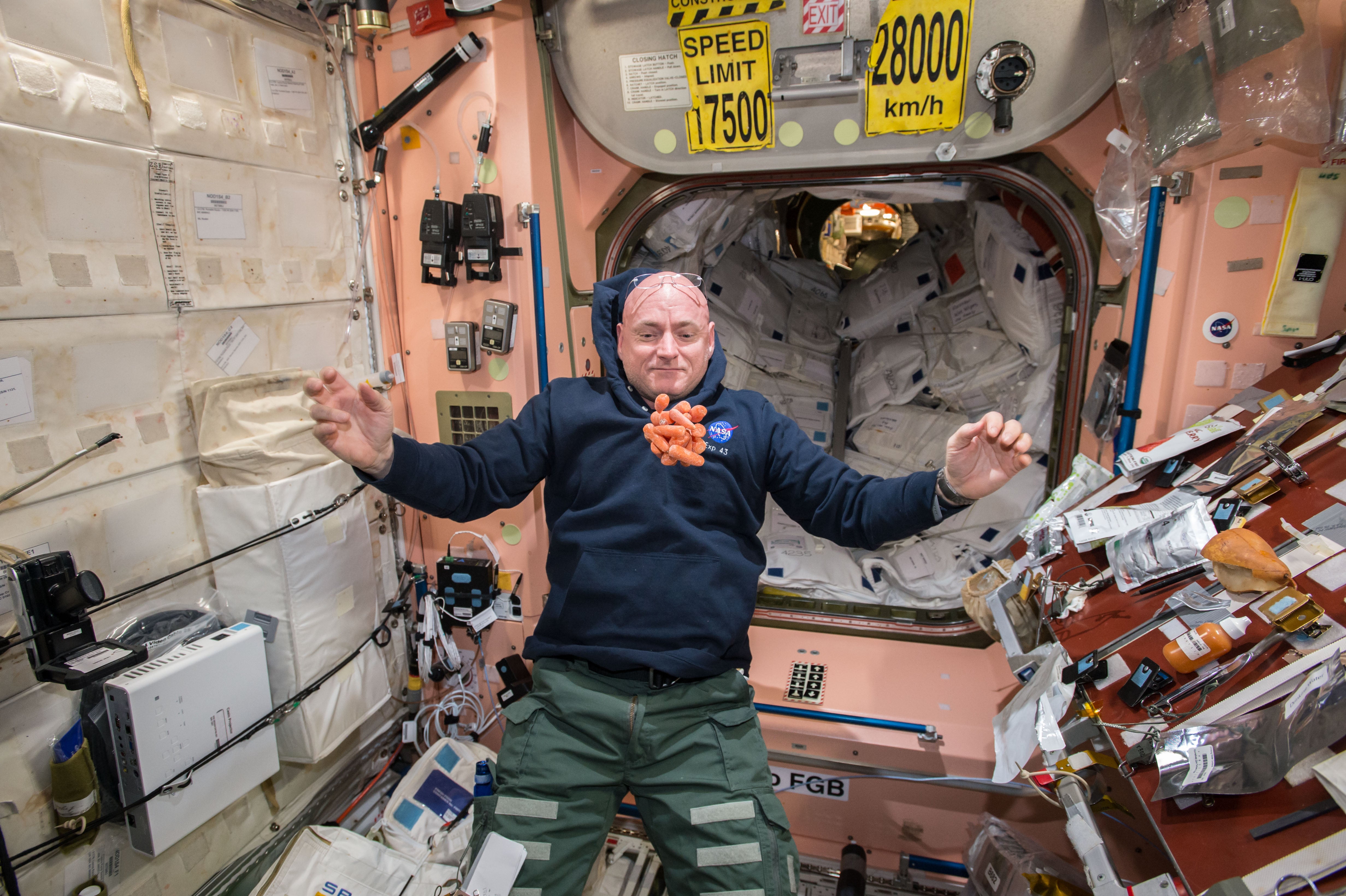

This makes sense since astronauts face enormous pressures. To start with, they spend their days in a hostile environment. Microgravity makes it much harder to do your job and does odd things to your body. Many complain of feeling worn down and fatigued as they adjust to the alien environment. You can’t get a proper night’s sleep either, since there are multiple sunrises and sunsets every “day”.

Then there’s the inevitable irritations with other crew – people not tidying up or forgetting to put the toilet seat down. And after a few months, space can get monotonous. The novelty wears off and being stuck in a box can start to grate.

Dietrich Manzey is a psychologist who works with the European Space Agency (ESA) and has regular one-to-one calls with astronauts. Many struggle with their inability to provide support to loved ones on the ground, he says. There is also a lot of work stress. “They feel pressure to perform very well, but you can’t do everything well,” he points out. And today’s astronauts must also be on social media representing the agency – that makes maintaining a work-life balance even more challenging. “Most astronauts want a weekend free, too!”

One of Stuster’s studies involved the analysis of 10 astronauts’ journals. Negative comments in the diaries include things like: “It is getting old being up here. The excitement has worn off after 2.5 months, but I still enjoy working here. It is the living up here that is old. It would be great to eat, sleep, shower, etc, at home and then go to work on the station.”

The one thing that almost all of them say improves the mission is the fact of seeing the Earth below them. They love seeing the planet and realising there are no boundaries between us, and that we are all one people

Sometimes space causes more significant psychological issues. For example, a 1976 Soviet mission was stopped when crew members began to report a strange odour in the ship. The source of the smell was never found, and the replacement team didn’t notice anything unusual, which suggests the first crew were experiencing a shared delusion. Another mission was affected when a cosmonaut fell into depression. And Ewald recalls the story of one astronaut whose relationship with mission control deteriorated to the point that he refused to talk with them.

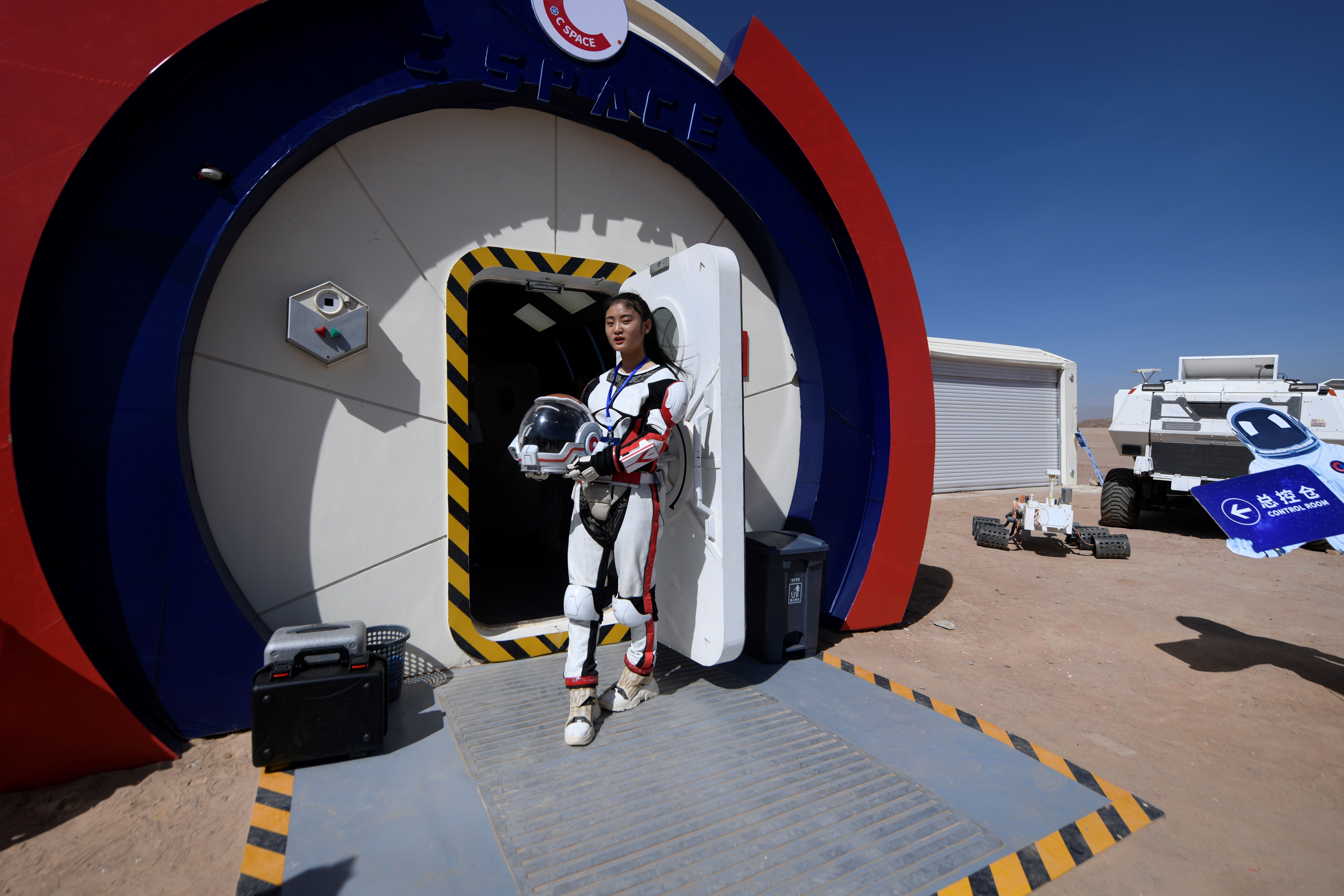

Kim Binsted, a scientist at the University of Hawaii, is the lead researcher on HI-SEAS, a project on a remote landscape of Mauna Loa that is reminiscent of Mars’ surface. Several crews of five or six astronauts have been sent to the location for up to 12 months at a time. Once they arrive they live in a pod and perform experiments as if they were on the planet itself. One of the research goals is to assess the psychological effects of time in this environment.

Isolation can do funny things to the mind, Binsted explains. One astronaut, Kate Green, reported a particularly long moment of jamais vu a few months into her mission. Jamais vu usually lasts no more than an instant, yet Green just couldn’t recognise one of her colleagues for about half a minute.

Then there’s loneliness. Until now, all astronauts have had the experience of seeing their home planet pass below them. But there is concern that the distance covered on a Mars trip could have profound psychological consequences. With their home planet either invisible or nothing but a faint blue dot in the heavens, what might this do to an already-stressed astronaut’s mental health?

“It is more of a philosophical question,” says Manzey. “What does it mean losing view of the Earth?” At the very least this Earth-out-of-view phenomenon could “strongly amplify feelings of loneliness” – if not outright despair.

It is important to note that in all of humanity’s space history, there have never been any serious psychological episodes reported. Even the occasional conflicts between crew members are largely ironed out and there is usually enough room to get away from one another.

Indeed, many astronauts have a wonderful time floating above the planet. Nick Kanas, a retired professor emeritus in psychiatry at the University of California has studied the psychological states of astronauts. “The one thing that almost all of them say improves the mission is the fact of seeing the Earth below them.” Watching the planet slowly spinning on its axis in all its beauty means many have something of a universalist experience. “They love seeing the planet and realising there are no boundaries between us, and that we are all one people.”

Early astronauts were normally selected from a military background and were portrayed as heroes in the popular media. Selection involved seeking out people with specific physical and mental characteristics, or the “right stuff” as a 1979 Tom Wolfe book on early astronauts put it.

Over time, however, our ideas around astronaut selection have advanced. Dr Manzey of the ESA describes the kinds of people that space agencies seek out. “It is not necessary for astronauts to have peak performance in all areas” – whether that’s in terms of mental abilities, emotional skills or interpersonal capabilities. “Instead, you need people who do not have weaknesses in any areas.” So besides being academically brilliant, selection teams are looking for an all-rounder who is fit and healthy, deals with stress well and doesn’t go to the extremes on any measure of personality. “This kind of person is quite rare,” Manzey notes.

Manzey adds that “it is beneficial for the mission to be a little more introverted”. Astronaut selection teams are looking for “the sort of individual who can be satisfied with just themselves and a little social company – not too introvert or too extrovert”.

An astronaut also has to be patient and determined. You could spend 20 years being officially employed by a space agency but never spend more than a few months or even days in space. Ewald, who is now retired, recalls that “you have to cope with a lot of disappointment”, having missions cancelled or not being selected.

Astronauts are also very high achievers, used to being the best in their class at most things they do. But in space they have relatively little control over their time and tasks. Manzey says: “You want a sort of brave, highly curious person, but at the same time someone who will accept having very little freedom over what they do.”

“In my humble opinion, you should have people who are interested in the voyage itself,” suggests Ewald, when thinking about how a Mars team should be composed. For example, “you want a particle physicist who is fascinated by every grain of dust captured just on the flight there”. These people should be fascinated by the trip itself, as much as the destination.

Psychological and social research with astronauts has led to a number of innovations in the way crews are composed and their missions planned.

At the HI-SEAS project on Hawaii, Binsted explains that astronauts are unlikely to tell mission control they are feeling anything but fine – they don’t want to get deselected for seeming like a complainer. So more passive measures are used to assess the crew’s mental state. For example, each individual has to wear psychometric patches on their skin. This could tell if certain staff are avoiding one another, or if their pulse rises in another astronaut’s company.

The research also reveals some interesting findings about crew formation. For example, having a more diverse crew is beneficial. “It’s not just in terms of gender or nationality, but also people with diverse experiences and skills.”

Astronauts who took part in the experiment have learned from earlier crews about what did and didn’t work. For instance, one group “decided to make crew cohesion a mission task, so on their white board they’d write a task to do something together each day”. That might be completing a puzzle, or telling each other about family members.

One of Stuster’s research projects for Nasa involved an analysis of historical journeys where people have been isolated for long periods in harsh circumstances – missions to Antarctica or the bottom of the ocean, for instance. By studying the coping mechanisms of earlier explorers, he developed several recommendations for activities that dissipate tension or avoid the formation of conflicting sub-groups on space missions. This might be things like writing a journal to blow off steam, eating a meal together each day or celebrating special events such as birthdays.

Stuster says that many of these recommendations would be appropriate for people stuck at home during lockdown too. He suggests celebrating special events to mark the passing of time and having frequent meals with the people you’re living with is good for morale. Board games are also helpful – although it’s wise to avoid competitive ones (Risk is particularly likely to cause fights, it seems).

Right now, several space agencies and private companies have talked about plans for a manned voyage to Mars, and it’s plausible that humans will have reached the planet before the end of this decade.

Whoever is finally selected for that first mission can certainly expect fame and glory on their return. After all, being the first people to set foot on another planet is rather special. But after living through several months of lockdown, the rest of us will also know that the realities that crew experiences might not be quite so pleasurable either.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments