Despite a history of prohibition, Russians are still battling with alcohol – and not just vodka

In 1913 five per cent of the Russian population was alcoholic. Today, it's 15 per cent. Mindful of the ailing health of its citizens – and the economy – various governments over the past 100 years have sought to ban alcohol, with mixed results. Mick O’Hare explains

We can probably assume absolutist monarch Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and Vladimir Lenin, the Bolshevik revolutionary who displaced him in 1917, didn’t see eye to eye. Coming from opposite ends of the political spectrum they were always likely to have their differences. Travellers and Benito Mussolini wanted the trains to run on time, but that doesn’t mean they were constitutional bedfellows. But when it came to imbibing, Nicholas and Lenin were in accord.

They were not drinking buddies – one can only imagine the rancorous pub arguments had they been so. Instead both saw merit in the sobriety of their citizens and both saw drunkenness as politically damaging to their aims. And with successive Russian leaders demanding their citizens eschew the bottle, so was born Russia’s era of prohibition, the first of many attempts to get the nation to ditch the drink.

Many people have heard of Al Capone, the American gangster, bootlegger and, ultimately, tax evader who got rich on the back of selling illicit booze in Prohibition-era 1930s Chicago. Probably too many movies and TV shows have been devoted to his life of crime. Indeed the era of prohibition in the US has spawned a folklore all its own. But how many people have heard of Anatoly Gryzlov? No Russians outside the city of Vyatka (now called Kirov) 950 kilometres to the east of Moscow have heard of him, and today most of its citizens have no idea who he was. He doesn’t turn up on Google, and there are no movies and books devoted to his escapades. And it’s possible he had many an alias. Yet, according to Sveltlana Petrova, aged 82, Gryzlov was Capone’s Vyatka equivalent, moonshining his way through the First World War, the Russian Revolution and beyond.

Who for that matter knew that Russia, followed by the Soviet Union, even had prohibition, and that it predated the American era? Prohibition of alcohol began in the US when the 18th Amendment to the Constitution was signed in 1920. By then the Soviet Union was already into the sixth year of its sukhoy zakon or “dry law”.

“Just like America, bootleggers got rich on the back of Russian prohibition,” says Petrova. “But unlike in America, law enforcement often turned a blind eye. They were missing their booze too and Gryzlov knew how to keep them quiet. My grandfather often talked of him. Unlike the American bootleggers, he was a decent man. Sure he got rich selling his pretty rough samogon [or moonshine] to the locals, but he wasn’t violent and nobody would tell the authorities what he was up to because they wanted their weekly bottle. And anyway, he wasn’t stupid, people in the police station and local government were getting theirs too. My grandfather says Gryzlov was a tall man with a stoop and a huge nose, and nothing like Robert de Niro…” she jokes, referring to Al Capone’s most famous on screen-portrayal.

Of course, Russians still have a reputation as serious drinkers, but interestingly, back in the early part of the 20th century, they were downing less alcohol per capita than the populations of France, Italy, Germany and Britain. Crucially though, it was nearly always in the form of vodka, whereas the other European nations favoured beer or wine. And when Russians drank, they did so with gusto…

Just like America, bootleggers got rich on the back of Russian prohibition. But unlike in America, law enforcement often turned a blind eye. They were missing their booze too

In 1913 it was estimated that one-twentieth of the population of Russia’s urban areas were alcoholics. “It was a problem back then,” says Petrova. “My grandfather saw a drunk worker fall into a grain mill. There was nothing left of him. And in winter, men walking home intoxicated would get lost and sometimes only found when the thaw came and they could locate the body from the smell.”

The Russian government had long been concerned about the prodigious intake of its population but was reluctant to impose restrictions, fearing civil unrest and the creation of an illicit and unregulated economy. But the onset of the First World War in 1914 was a gift to prohibitionists in the Duma. Russia needed a ready supply of sober soldiers and Tsar Nicholas outlawed vodka and other alcohol sales for the duration of the war. He had seen the consequences of drinking among the ranks.

In the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-45 drunken conscripts had created grave disciplinary problems, contributing to Russian defeat. And as Nicholas travelled the nation ahead of mobilisation in 1914 the historian Sergei Oldenburg wrote that the tsar witnessed “family poverty and neglected business” as a consequence of insobriety. He had already vowed to end the sale of “something that destroys the spiritual and economic powers” of his people.

Ironically, the tsar wouldn’t see the end of the conflict, abdicating in 1917 before refusing exile and then being executed in 1918 following the Bolshevik revolution, yet his prohibitionist policy didn’t die with him. When Lenin seized power in November 1917 and Russia became part of the newly created Soviet Union he retained the edict, figuring that sober citizens, well-fed using the grain that would otherwise be used for making vodka, would more likely be supportive of his new regime.

But both the revolutionary and the monarch before him were provoking unintended consequences, not least a huge fall in state revenue from taxes and duties which after three years of war and revolution, was when the nation needed it the most. They also had to deal with the consequences of 300,000 people employed in the alcohol trade suddenly finding themselves out of work. Indeed, British prime minister David Lloyd George had foreseen the problems that might arise, describing Russian prohibition as “the single greatest act of national heroism”. He was right and prohibition did not have the effect intended. Meanwhile, people squirrelled away grain, vegetables, even sawdust – anything that could be distilled and turned into samogon.

In areas where the authorities were able to uphold the ban there were dramatic drops in crime, improved health, fewer suicides (even to the point where there was a shortage of corpses for training medical students)

But in areas where the prohibitionist authorities were most zealous there were riots. Prior to the revolution, police were frequently ordered to fire on protestors demanding vodka, and the governor of what was then the Perm Oblast appealed to the government to allow sales of alcohol for two days a year as a safety valve to “avoid bloody clashes”. And after the revolution the Bolsheviks were forced to close even those distilleries producing medicinal alcohol, after they became the focus of more rioting.

Even so, there were positives to the ban. In areas where the authorities were able to uphold it there were dramatic drops in crime, improved health, fewer suicides (even to the point where there was a shortage of corpses for training medical students), and better economic growth as workers spent money on things other than booze. In Voronezh the police stated that “in the first half of July 1914, when the vodka dispensaries were open, there were 27 murders or other serious crimes. In the first half of August, when the vodka shops were closed, there were only eight”. Police in Ekaterinoslav, now in Ukraine but then in the Soviet Union, reported that “crimes attributable to drunkenness have wholly ceased. There has not been a single case of murder, robbery, assault, or hooliganism. [Before the ban] there were more than a hundred every month.”

“My family lived in Berezniki, an area where the alcohol ban was pretty much enforced,” says Oleg Ovechkin, aged 86. “The only time my father got a bottle or two was for a family wedding or funeral – no Russian funeral is complete with vodka. So family members would bring them when they travelled to our region.”

Elsewhere though, hooch was in abundance. Just like the United States, it was impossible to stop the population from drinking. In Moscow markets, by asking for a “lemonade” and winking at the stallholder you could secure yourself a bottle of moonshine. It became a cottage industry all of its own. In the first half of 1923 in Ukrainian Kharkov 2,310 stills were confiscated. And when the stills were closed and samogon couldn’t be distilled, people would drink varnish, perfume and polish. In fact these industries had a mini boom catching the government unawares until they figured out why people were falling sick. And, as in the United States, it became clear that the alternatives to uncontaminated, correctly distilled alcohol were proving far more damaging than the real stuff itself.

“My grandfather, a police inspector in Kursk Oblast, pleaded regularly with local politicians to do something about it,” says Yuri Aleksandrov, aged 69. “He told me of weekly meetings where he turned up with a file listing deaths from drinking poor samogon or furniture polish. One man had jumped from the church spire thinking he could fly, another shot his four young children thinking they had been sent by Satan to kill Lenin. And my grandfather also took with him files from before the ban in 1914 listing deaths from properly distilled alcohol. When the former began seriously outstripping the latter the politicians knew they had to act.”

He turned up with a file listing deaths ...One man had jumped from the church spire thinking he could fly, another shot his four young children thinking they had been sent by Satan to kill Lenin

Despite the new socialist state (presciently it turned out) believing that alcohol was likely to usurp the utopian ideals on which it was founded, the government gave up the ghost. On 1 October 1925, sukhoy zakon was abolished. Some reported dancing in the streets, but Aleksandrov said his aunt “wept with fear”. She had lost her elder brother to alcoholism and was scared her children and grandchildren could meet a similar fate at the hands of the newly opened distilleries.

The same fears preyed on the minds of other politburo leaders in subsequent decades and, Joseph Stalin aside – the Georgian leader liked to knock a few back between purges and appreciated the revenues alcohol duties brought into the state coffers – temperance was rarely far from their thoughts. Consequently, the history of the USSR is punctuated by frequent campaigns to encourage sobriety.

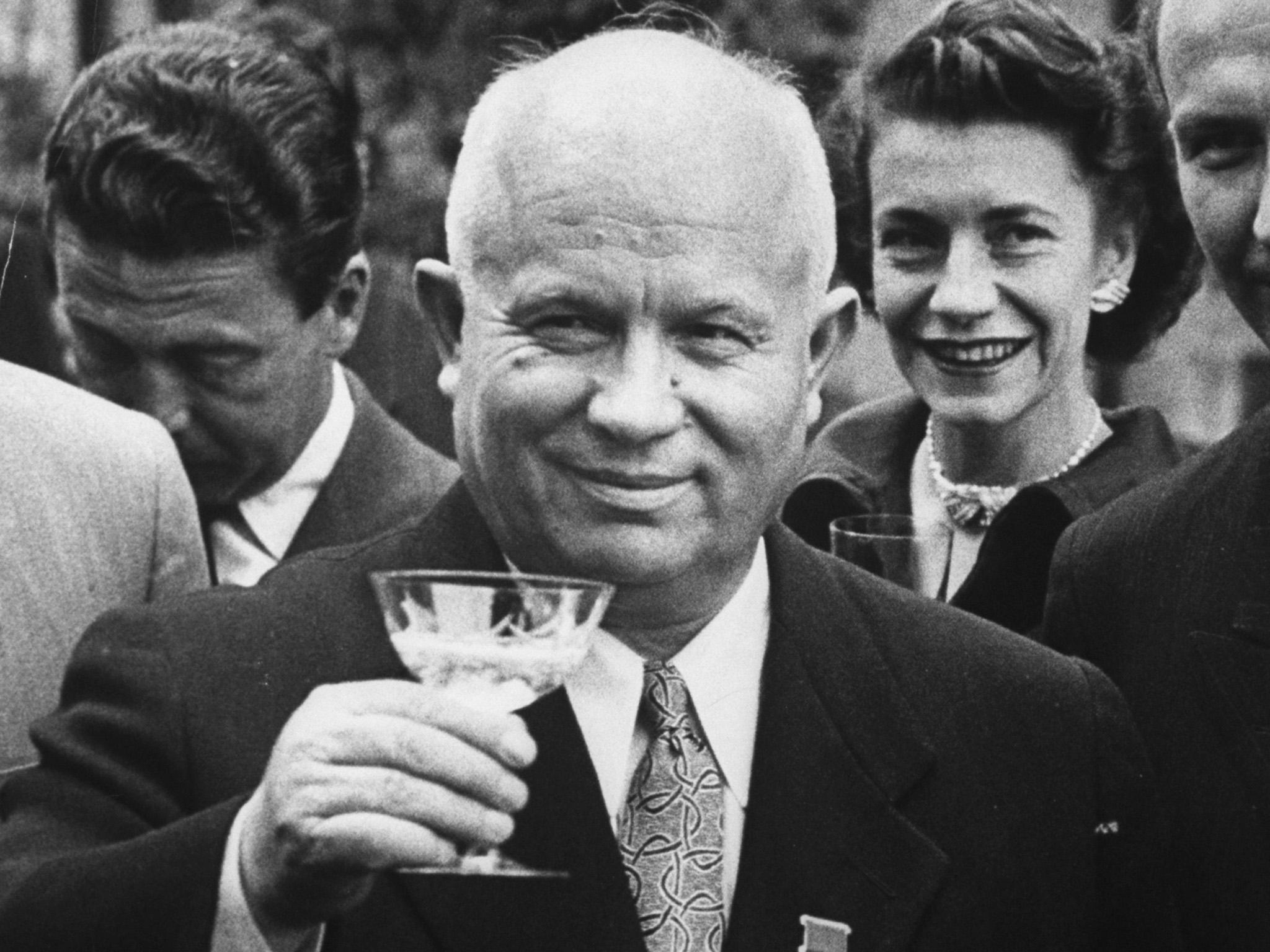

One of the first acts that Nikita Krushchev undertook when he eventually succeeded Stalin as general secretary of the Communist Party after a power struggle with Georgy Malenkov in 1958, was to attempt to reduce alcohol consumption. While Stalin had appreciated vodka’s contribution to state income, the obvious negative was a renewed rise in alcohol related ill-heath. And in 1972, general secretary Leonid Brezhnev also regarded Russian consumption of vodka as dangerously high, leading to a slump in manufacturing and agricultural productivity. Another campaign was launched with limited results.

So Gorbachev had a point, I was drinking too much, the whole of the USSR was drinking too much, but just telling people to stop wasn’t going to work

But, prohibition aside, perhaps the most concerted attempt to stop the bibulous inclinations of Russians was that undertaken by Mikhail Gorbachev, who came to power in 1985. Gorbachev was a reforming leader, dead set on restructuring the lumbering Soviet economy through his system of perestroika. History has shown that things didn’t work out for the USSR exactly as Gorbachev planned despite his good intentions and it might be argued that his anti-drinking initiative was a metaphor for his political career.

The stories may be apocryphal but, amid the decline of both its centralised economy and its international influence, the population of the Soviet Union took to drink. And not just vodka – apparently anything containing alcohol was fair game if the genuine stuff was unavailable: perfume, distilled industrial solvents and glues, even toothpaste in the USSR contained alcohol which could be extracted. Fancy insect repellent anyone? Or antifreeze? The more modest would just buy boxes of liqueur chocolates.

“It was crazy what we’d drink back then,” says 62-year-old Lukas Butkus from Vilnius (Lithuania was, of course, then part of the Soviet Union). “I really did drink perfume once, but mainly it was vodka, either badly produced or home-distilled. So Gorbachev had a point, I was drinking too much, the whole of the USSR was drinking too much, but just telling people to stop wasn’t going to work. So although I remember the rather groovy posters I don’t remember anybody stopping drinking.”

But Gorbachev had been getting desperate. Consumption had risen steadily through the previous three decades. In the early eighties the figures made grim reading. Drunk driving accounted for 14,000 traffic deaths a year and tens of thousands of serious injuries. Alcohol was implicated in violence against individuals, including murder, in 75 per cent of cases, even higher in cases of domestic violence against a spouse or a child. As much as 20 per cent of disposable household income was being spent on alcohol, amounting to about half a litre of vodka for every adult male every two days. Suicide rates had soared as the economy struggled. Healthcare was under strain and underage drinking was a virtually accepted phenomenon. As well as the toll on human life it was estimated that in 1985, when Gorbachev came to power, $8 billion was being lost in economic productivity to booze every year.

Russia’s history of consumption goes back centuries, of course. It is part of what is known as northern Europe’s Vodka Belt. Soldiers in the Red Army had a daily ration of vodka for example, and it is widely celebrated in music and song. But the failing economy added another deeper layer to an underlying issue. Alcohol had become an escape.

So in May 1985, just two months after he had come to power, Gorbachev and the politburo passed the “Measures to overcome Drunkenness and Alcoholism”, again popularly known as the “dry laws” and the most stringent anti-booze measures since prohibition ended in 1925. State production of spirits was severely curtailed, by as much as 40 per cent. Shops were licensed and alcohol could not be sold before 2pm. Patrons were limited to a bottle of spirits, or two of wine. Restaurants could not sell hard liquor at all, and the drinking age was raised to 21.

She was screaming at him saying he would lose his job. And he said ‘I just ate yoghurt. Sometimes it ferments in your stomach’

Any home production of alcohol could lead to imprisonment. Vodka was even banned at Soviet state events. If you wanted booze at your wedding, you had to make sure you filled out the paperwork, otherwise your guests would be disappointed (although consummation of the nuptials was presumably more likely to succeed). Prices also increased, by 1986 a bottle of vodka cost 25 per cent more than it had the previous year, and there were penalties for intoxication – workers could be fined their weekly wage for turning up drunk.

Raisa Kvitko, 41, now a teacher in Belgorod, remembers her mother being furious with her father when he was accused of turning up to work smelling of drink. “She was screaming at him saying he would lose his job,” she remembers. “And he said ‘I just ate yoghurt. Sometimes it ferments in your stomach’. Which was quite funny in retrospect, but when I was a little girl I got quite scared that he might be fired.”

To replace the bibulous gap in his citizens’ lives Gorbachev insisted local authorities build new leisure parks and sports clubs and engage the population in cultural activities. He also demanded improvements in healthcare to treat addiction and new preventative programmes.

All these measures were backed by a huge propaganda campaign, featuring the posters that Butkus found so appealing but ineffective, and a new national temperance campaign was launched garnering 14 million members (how many had previously been adherents of the bottle, however, is unrecorded). The western notion of the vodka-swilling Russian, forever toasting his largesse and smashing glasses on the fireplace was under threat. Meanwhile general secretary Gorbachev became known as the mineral’nyi sekretar’ (mineral-water-drinking secretary).

But seemingly, despite Batkus’s scepticism and against the likely odds, the campaign scored some successes – some people did stop drinking. Statistics suggest that the campaign reduced annual deaths by as many as 400,000 per year. “To be honest it changed my life around,” says Dmitri Kantorovich now aged 59. “I just needed it pointing out to me. But obviously alcohol is addictive so I might have been in a minority, many people wouldn’t find it easy to stop overnight.”

Kantorovich was so inspired that he now works as a counsellor for addicted teenagers in Rostov Oblast. And while some statisticians have argued that the positive effects were short-lived and, in the long term, insignificant there was also a marked fall in criminality and a rise in life expectancy. Alcohol-related accidents were reduced as were stillbirths. And, pleasingly for the moribund economy, productivity improved.

The Russian exchequer, however, suffered accordingly. Tax revenue on spirits plummeted, and by more than would have been expected as the black market began to replace curtailed legal trade. “Sugar pretty much disappeared from stores as soon as it arrived,” says Kvitko. “It was a necessary part of making samogon.”

Illegal stills sprang up, even in central Moscow. “You could always spot where they were in your neighbourhood,” says Kantorovich. “The moonshiners used to use a rubber glove to vent off the samogon vapours which led to the gloves billowing in windows and giving us what we called the ‘Gorbachev Wave’.” Of course the moonshine was often of dubious and dangerous potency and while state production had not exactly ensured a healthy nation, it certainly led to fewer deaths from poisoning.

The moonshiners used to use a rubber glove to vent off the samogon vapours which led to the gloves billowing in windows and giving us what we called the ‘Gorbachev Wave’

Unsurprisingly, the campaign was unpopular with the general population, best expressed in the old joke about the man standing in a long queue at the vodka shop in the freezing cold who announces that he is going to kill Gorbachev and heads off to the Kremlin. When he gets back his friend asks if he did it. “Nah,'' says the would-be killer, “the queue for that was even longer.”

But by the time the campaign ended in 1987 it was considered to have failed, and when Gorbachev’s successor Boris Yeltsin (a heavy drinker, as anyone who watched him fail to exit his presidential plane at Shannon airport in 1994 will recall) came to power he abolished state monopolies on vodka and spirits. He pointed out that the promised rise in economic productivity in no way offset the losses in taxation. And he needed the cash.

So did it serve a purpose? Did its successes, however brief or contestable, make it a worthwhile exercise? Today Russians drink nearly 16 litres of pure alcohol per adult per year, putting it fourth in Europe, which while not the highest, in terms of spirits consumption it tops the table. And the price, once again, has fallen to levels where, unlike during the Gorbachev campaign years, the average Russian can easily afford to drink. This may explain why a fifth of Russian males die of alcohol-related causes, four times as high as in the rest of the world.

The atlantic.com website has pointed out that nearly 15 per cent of Russians are alcoholics. David Zaridze, visiting professor of epidemiology at Oxford University, has estimated that the increase in alcohol consumption since 1987 has caused an additional three million deaths nationwide. This disproportionately affects males who on average live 10 years less than Russian women. And although Vladimir Putin has expressed concern, in 2010 his finance minister Alexei Kudrin suggested the best thing Russians could do to help “the country’s flaccid national economy was to smoke and drink more, thereby paying more in taxes.” As noted before, it’s a cultural thing…

Others have been even more cynical saying that, Gorbachev aside, Russia’s leaders have been more than happy for the population to be permanently sizzled, ensuring the people were in no state to foment political discord. It’s a notion Kantorovich riles at. “Russia has a drink problem, I know, I work with it,” he says. “But society still functions. I go abroad sometimes and I see more overt drunkenness in western European cities and holiday spots than I ever see in Russia. Russians are perfectly capable of understanding the issues that face the nation,” he argues vehemently. “Drinking is just part of our culture as it is in Britain, Germany or Poland. Nobody accuses those nations of being unable to run their own affairs because everybody is drunk.”

Russians are perfectly capable of understanding the issues that face the nation. Drinking is just part of our culture as it is in Britain, Germany or Poland. Nobody accuses those nations of being unable to run their own affairs because everybody is drunk

And, like other commentators, Kantorovich argues that Gorbachev was successful and would have continued to have been so if the political uncertainties caused by the fall of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe hadn’t overtaken his efforts. Consumption of spirits in Russia grew by 233 per cent in the 10 years between the end of his campaign and 1998, suggesting that it was having an effect before it was terminated.

In the American Economic Journal Jay Bhattacharya, Christina Gathmann, and Grant Miller have argued that Russia’s 40 per cent surge in deaths between 1990 and 1994 was caused more by the demise of Gorbachev’s campaign than the difficult political transition from communism to a market economy. As ever, the truth may lie between the two competing theories. Nonetheless, the researchers present evidence that shows deaths closely related to alcohol consumption such as circulatory disease, accidents, violence and alcohol poisoning, rising following the cessation of the campaign in 1988. This suggests that the 400,000 fewer annual deaths during the campaign could be an accurate figure.

Gorbachev has partially defended his campaign, although he has admitted it was probably too fast and sweeping and that patience was lacking. Anna Dolgov, writing in the Moscow Times in 2015, reported the former leader as saying that although the campaign might have made mistakes he should have persisted. “We should not have shut down trade, provoking moonshine production,” he said. “Everything should have been done gradually.” Maybe the campaign’s greatest error, as with American prohibition, was that the government failed to take note of the fact that humans, in the main and given half a chance, enjoy getting sloshed. And although Gorbachev had the support of many Russian women he regrets that he bowed to pressure from the disgruntled male half of society and also to the Russian exchequer which was despairing over its loss of tax roubles.

And so Russia’s love affair with vodka rumbles on, and since the 1980s when soldiers returning from the Soviet Union’s war in Afghanistan began to bring heroin, narcotics have entered the scene too, while Russia’s own contribution to the world drug scene, Krokodil (named after its propensity to make the skin scale), has created a whole new headache for the authorities. It’s super cheap and super deadly. But booze remains at the top of Russia’s favourite addictive substances.

Of course, as Kantorovich points out, Russia, is not the only nation with a booze problem. It would be unfair to suggest it is. And despite high consumption rates, alcohol related deaths have recently been falling in Russia as modern forms of treatment, previously available more readily in the west, have been introduced. Russia’s chief sanitary inspector, Gennady Onishenko, has urged increased spending on the treatment of alcoholism, and some of Gorbachev’s original programmes have been reintroduced, minimum alcohol pricing and restricted sales hours among them.

Perhaps more significantly, younger people, as in Britain and elsewhere, are not necessarily following their parents into regular drinking. Indeed, despite all of the above, many Russians – some of them internationally lauded – are and have been teetotallers, Leo Tolstoy among them. The writer once founded a temperance society and wrote an essay entitled “Why do men stupefy themselves?”

As we know there are numerous reasons why people drink alcohol, chief among them that – at least in the short term – it feels good, and also because it’s addictive, something, for whatever reason, non-drinkers and governments seemingly fail to take into account. Tsar Nicholas, Vladimir Lenin and Mikhail Gorbachev probably had very good intentions, but they committed the error of not allowing for human ingenuity. There’s always a way around a booze ban. It’s a mistake Al Capone and Anatoly Gryzlov were never likely to make.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments