‘A Polish national hero’: 30 years on from Poland’s first democratically elected president

The enduring popularity of Lech Wałęsa is remarkable. Especially given the stunning revelations that he was once an informant for Poland’s communist-era secret police, writes Mick O'Hare

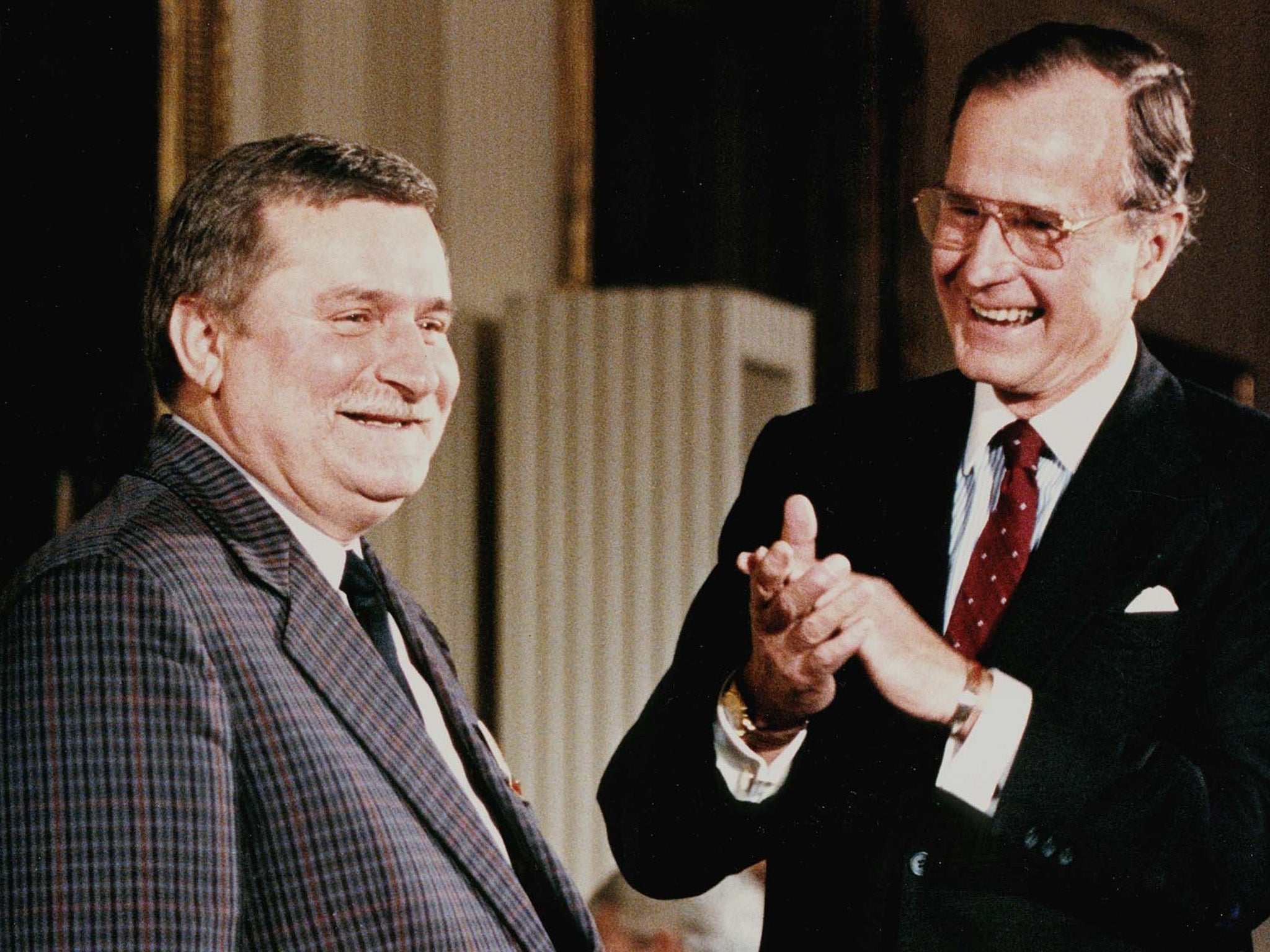

It had been a long time coming. Seventy-two years after it became a permanent nation state, and after enduring both Nazi and communist rule, Poland finally inaugurated its first democratically elected president on 9 December 1990. It’s now 30 years since Lech Wałęsa, a former Gdansk shipyard electrician, comfortably beat his rival for the candidacy, Stanisław Tymiński, in the final run-off to become the first head of the free Polish state.

Wałęsa, who led the trade union Solidarność, or Solidarity, in its fight for democracy against the communist government of General Wojciech Jaruzelski, had become the most prominent and vocal of those fighting the one-party states that were beginning to crumble across eastern Europe in 1989. To those in the west, he was the face of the revolutions sweeping across the former Soviet Union satellite states and he would go on to win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983 after being named Time magazine’s Person of the Year two years earlier. He is still feted outside his homeland; an honorary citizen of more than 30 cities worldwide, he has honorary degrees at more than 40 universities, honorary doctorates at 45, and has been decorated by more than 30 nations including receiving Britain’s Order of the Bath, France’s Légion d’Honneur and the United States’ Presidential Medal of Freedom. His renown even extends to sporting bodies and musicians: he owns an honorary karate black belt while U2’s hit single “New Year’s Day” was inspired by Wałęsa.

Earlier this year The Independent ran a top 10 of “Prophets not without honour but in their own country” – a triple negative meaning somebody loved outside their own nation but reviled closer to home. Wałęsa was not among them. Despite his crushing defeat ending any serious involvement in politics in the 2000 presidential election, he is still as popular in Poland as he is elsewhere. And that is noteworthy considering the contemporary standing of other prominent figures from that revolutionary year of 1989. Václav Havel in Czechoslovakia fell victim to an unfulfilled economic dream and ill-judged foreign policy, Miklós Németh in Hungary was seen as too close to the old single-party state and, most notably, the Soviet Union’s Mikhail Gorbachev – inadvertent architect of the demise of communism in eastern Europe – is generally despised at home, seen as the man who single-handedly dismantled Russian pride.

Not so for Wałęsa in Poland. Almost two-thirds of the population still say that his role in the downfall of communism means he is guaranteed his place as a Polish national hero. Just as wartime leader Winston Churchill was rejected by British voters in the general election of 1945 but retained the gratitude of a nation, so it is with Wałęsa. Despite his fall from electoral grace in 2000 the 77-year-old is still a man Poles choose to listen to.

This popularity, considering the fate of his contemporaries in other former Eastern bloc nations and the ever-shifting fault lines of the region’s politics, is quite remarkable. But what makes it positively surprising is that the reverence for his achievements has withstood the stunning revelation that Wałęsa was once an informant for the Służba Bezpieczeństwa (SB), the despised Polish communist-era secret police. To what extent and in what capacity is a matter of conjecture, but there is no question that at some stage in his trade union past, Wałęsa was apparently employed by the other side. Had the exposé emerged in 1989 that the man who more than anybody was internationally recognised as being in the vanguard of the opposition to communism had skeletons in his closet – maybe skeletons posing as double agents, but skeletons nonetheless – the outcomes of that year of dissent behind the Iron Curtain might have been notably different, in Poland and beyond.

Rumours were already rife when, in 2008, a book written by two members of the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) was published. The institute had been set up to investigate and prosecute crimes committed while Poland was under first Nazi and then communist rule and to inform the public about the authorities and their actions during those eras. Among many archives it inherited were ones containing secret police files. And Wałęsa’s name, claimed the authors, was prominent among them.

The accusations weren’t new. Back in 2000, while Wałęsa was running his final presidential campaign, the Appellate Court of Warsaw had concluded that he had not collaborated with the SB although he had been taken in for questioning, which explained why Wałęsa’s signature had appeared on documents. In his defence Wałęsa said that anybody in his position, in direct opposition to an autocratic government, would have been a person of interest and that while he may have been forced to sign documents marking him out as an informant while under duress, he had never provided the SB with information on subversive activities nor any of his fellow dissenters and trade unionists. In 2000, the court accepted his explanation, although opponents insisted that he was merely cleared on a technicality (vital documents from the archive appeared to have gone missing, possibly destroyed post-revolution).

Two of his former allies, Piotr Naimski and Antoni Macierewicz, testified against him. It was they who, in 1992, while Wałęsa was still serving as president and after studying administrative records, had first placed him on a list of 64 members of the government who were named as SB spies or collaborators. The 2000 court ruling was Wałęsa’s first attempt to clear his name, followed in 2005 by the IPN going further by deeming him a “victim of the communist regime”.

Yet it would be the same institute that would provide the information for the 2008 book. The SB and Lech Wałęsa: A Biographical Contribution by Sławomir Cenckiewicz and Piotr Gontarczyk, would reignite the debate about Wałęsa’s past and this time the evidence was more conclusive. The authors alleged that files showed Wałęsa operated under the codename Bolek and that he had worked for the SB during the 1970s. Apparently he wrote reports about colleagues in the Gdansk shipyards who were later persecuted by the security services as well as informing on coworkers listening to western European radio services. They also had receipts that documented how much Bolek had been paid for his information – approximately four times the average worker’s salary.

But perhaps more damning, the book alleged that Wałęsa had used his position as president to locate and destroy incriminating documents in the national archive and that an investigation into the missing files had been closed down by higher-ranking officials. His opponents were quick to point out that the 2000 court case had ruled in Wałęsa’s favour because key documents could not be located. Lech Kaczyński, the president of Poland between 2005 and 2010 until his death in a plane crash was convinced Wałęsa was an SB agent. Along with his brother Jarosław, Kaczyński was the founder of Poland’s right-wing populist Law and Justice party which currently has a majority in the Polish parliament. Ironically both once worked with Wałęsa in opposition to Jaruzelski. But Wałęsa has long been an opponent of what he sees as an autocratic regime, even renouncing his Solidarność membership due to its tacit support of Law and Justice. “They like to destroy before they have any idea what they will build in its place,” he has criticised.

Law and Justice prime minister Mateusz Morawiecki says Wałęsa only opposes them because the party intends to release more government files and fears he may feature further in them, including rumours that he was still under the control of former SB operatives during his presidency who were threatening to blackmail him. Wałęsa, for his part, insists that Law and Justice want to rewrite Polish history, replacing him with their own version of events.

If he was an agent he was a pretty terrible one, bringing down the regime he was supposed to be working for. They could never forgive Wałęsa for destroying their cabal and ever since have used anything to humiliate him

Initially, Wałęsa denied having seen his SB file at all but later admitted reading it while he was president before returning it intact to the archive resealed. “The file was, in any case, a forgery,” he insisted, “which was then stolen by somebody else and now that casts suspicion on me.” He threatened to sue the book’s authors but never did although in 2009 he did bring proceedings against Lech Kaczyński for continually repeating the book’s allegations.

His supporters saw the book as simply a means to discredit Wałęsa. Former Solidarność member Wladyslaw Frasyniuk said: “People who spit on history and its authorities are riffraff. These people haven't done anything to achieve an independent Poland.” Many voters sided with Wałęsa back in 2008 and do so now. “If he signed papers, so what?” says Anna Tokarczuk, a former healthcare worker in Kraków. “That’s what the police made people do. If he supported their regime why would he then oppose them on the front line in Gdansk? If he was an agent he was a pretty terrible one, bringing down the regime he was supposed to be working for. They could never forgive Wałęsa for destroying their cabal and ever since have used anything to humiliate him.” It is widely accepted that as Wałęsa was being nominated for the 1983 Nobel Peace Prize the authorities had attempted to discredit him by leaking information from their files, most likely forged. However, Irena Piasecka, a local government clerk in Warsaw, is more equivocal. “You need your leaders to be squeaky clean,” she says. “If he didn’t tell the truth at first, what else might he be hiding?”

The book certainly divided opinion. Former head of the European Union Council Donald Tusk, prime minister of Poland between 2007 and 2014, described the book’s accusations as “politically motivated” while even the deputy director of the IPN said the book was part of the Kaczyńskis’ attempts to disgrace Wałęsa and should not have been published under the institute’s name. Others were less supportive. “I think Wałęsa should have told us everything at the beginning. If he had, back in 1990 when he ran for president, people would have been forgiving, but letting it slip out bit by bit makes people distrustful,” says Jerzy Okolski, a delivery driver from Warsaw who now lives in London.

Unfortunately for Wałęsa, the book wasn’t the last of the allegations. Czesław Kiszczak was a former communist-era politician who effectively ushered in the transition to a multi-party democracy as the last communist-era prime minister, aligning with Solidarność and ensuring the revolution, when it arrived, was non-violent. This stance led some sections of post-communist Polish society to cut him some slack, but others point to his earlier role as minister of internal affairs which meant he was accountable for the actions of the SB. He had ordered frequent crackdowns on Solidarność and other organisations and individuals deemed subversive – internments and beatings were commonplace and most egregiously he was held by many to be responsible for the shootings of nine protesters at the Wujek coal mine in 1981.

Kiszczak was a meticulous record keeper and when he died in November 2015 his wife offered to sell documents and records he had kept at his home to the IPN for 90,000 zlotys (approximately £18,000). Instead police seized them. One folder contained 90 pages of reports plus an undertaking to work with the SB, handwritten and signed “Lech Wałęsa – Bolek”. A second folder contained reports purportedly collected by Wałęsa on his coworkers in Gdansk between 1970 and 1976 until the quality of information flowing from him was so poor the arrangement was ended. A letter found with the documents and written by Kiszczak said that he had kept them hidden to protect Wałęsa’s reputation. Presumably his wife had no such compunction although she later said she hadn’t read the letter.

I think Wałęsa should have told us everything at the beginning. If he had, back in 1990 when he ran for president, people would have been forgiving, but letting it slip out bit by bit makes people distrustful

The IPN approached a handwriting expert who verified the script was Wałęsa’s. There was “no longer any doubt” that Wałęsa collaborated, institute official Andrzej Pozorski decreed. The Law and Justice-aligned current president of Poland Andrzej Duda agreed, urging Wałęsa to “speak out and tell Poles the truth”. Historian Sławomir Cenckiewicz who has written much about the era described the findings as “shocking”.

Wałęsa, however, denounced the new documents as “forgeries” and accused the institute of “slander” (his legal team has also argued his writing has changed over the decades and the documents appear to be in his modern hand). While it is not a crime in Poland to have worked for the SB it is illegal to deny it if it is true. But Wałęsa stuck to his story. “Everybody knows the secret police forged documents about me,” he argued. “The historians are just repeating nonsense.”

And so the murky tale rolls on. It’s of little doubt that Wałęsa did have dealings with the SB, but so did many who took on the might of the communist state. Indeed it might be deemed even more suspicious if there were no SB records of one of their chief foes. But to what extent he was involved may never become apparent. Yet despite all the intrigue, perhaps of more consequence is what the people of Poland think of Wałęsa today in light of the slow drip of revelations down the years. Is his legacy tarnished forever?

Although the 2008 book sold in huge numbers, it didn’t necessarily dent the reputation of the man who, more than anyone, brought democracy to Poland for the first time. Perhaps the Kiszczak documents had more of an impact on how he was viewed by his fellow citizens but even so the level of respect Poles have for Wałęsa – especially those who remember 1989 – seems relatively undiminished. “When he won the Nobel the authorities tried to discredit him,” says Wojciech Sobolewski, now 82, who worked in the shipyards with Wałęsa. “The book was more of the same. The same old people, dragging up half-truths about the man who brought about their downfall. It didn’t work. Then there were new papers, what a surprise!”

When Wałęsa ran for president in 1990 he used the slogan “I don’t want to, but I have to”, and it’s an idiom that has perhaps served him well in the years since. He didn’t want to work for the security services but he had to, for the better good. Certainly some Poles see it that way. “It was a different era, a different time,” says Sobolewski. “When those people were persecuting you, you wriggled this way and that to find a way out and to remain true to your values. That’s what Wałęsa did. We all would have. It’s so easy to be critical in 2020.” “This isn’t the man who just freed us, he fed us too,” says Zofia Kowalska, the daughter of a stevedore who worked in Gdansk in the 1980s. “Food was rationed, Wałęsa demanded ‘freedom through bread’ and we got it. He was brave beyond belief and we should still listen to him now.”

Elder Poles also remember that Wałęsa was the man who negotiated the withdrawal of Soviet Union troops after 48 years on Polish soil and moved the country towards membership of Nato and the European Union. It’s his support for the latter, along with what he sees as the Law and Justice party’s attacks on Polish democracy, which has brought him into conflict with the mildly Eurosceptic government. And while this also endears him to more liberal Polish voters, personally Wałęsa is socially conservative and mindful of his Catholic upbringing. But he can adapt. His religious beliefs at first brought him into conflict with LGBT+ campaigners but he admitted he was wrong and changed his once negative stance on single-sex marriages. Even now he is still a pragmatic politician who knows how to roll with the punches and reposition himself in the public eye.

But there are other criticisms too. He has an attitude to immigration more in line with that of Viktor Orbán, the nativist prime minister of Hungary and others in the Visegrád group of eastern European nations, although this stance still plays well at home, if not in the more liberal democracies of the EU. He has also been accused of not paying his taxes which possibly damaged his reputation more than the allegations of collaboration. Wałęsa’s confrontational style, often leading sometime snobbish opponents to describe him as a rude, unsophisticated, uneducated peasant-made-good, not befitting of the role of president, has led him into conflict with his former allies in Solidarność among others. “Sometimes he just likes to pick fights, I fear,” says Jósef Tarkowski a local politician with the liberal Civic Platform party from Lodz. “He thinks because of who he is and what he did that only he can be right. So he’ll pick an argument with Law and Justice and when my party agrees with him he’ll pick a fight with us too.”

Wałęsa was also poor at handling the media, meaning he often received a bad press when stories surfaced about his past. “You don’t get anywhere in politics in Poland without being blunt and knocking heads together,” says Tokarczuk. “Wałęsa wouldn’t be pushed around. Which is good.” But while Jakub Mierzwa, a postal worker and Law and Justice party supporter, agrees he thinks Wałęsa sowed the seeds of his own political downfall by refusing to listen to good counsel. “He knew best,” he says “and even if other people actually did he didn’t want to know.”

Still, when taken in the round, Wałęsa’s reputation has survived far better than most of his eastern European political contemporaries from 1989. The painful metamorphosis from command economies to the free market meant that most were voted out in rapid succession – Wałęsa benefiting from Poland’s being one of the least tortuous transitions. And although it’s 20 years since he last ran for office, his standing among Poles, especially those who were around to witness the nation’s astonishing transformation in 1989, is generally undiminished. Many still refer to him as “President Wałęsa”. He may be irascible and captious, and give the impression these days of being a grumpy old man who cannot see anything positive about the world around him, but his continual defence of freedom of expression and the democratic institutions of state and the media in the face of sometimes unrelenting attacks from the populist government under Morawiecki have harked back to those heady days when Wałęsa fearlessly faced down the state apparatus.

Whatever the truth or otherwise of the collaboration allegations, and the extent to which any agreements Wałęsa came to with the SB were an attempt to protect himself, his family and his political allies, his epithet as the “man who freed Poland” perpetuates. His was the face – with its trademark walrus moustache – that symbolised the aspirations of Poles who had endured centuries of occupation and oppression, and his espousal of non-violent protest allowed him to occupy the moral high ground.

His Nobel citation described him as belonging to not just Poland, but the world. It described his personal sacrifice in the face of a repressive state, his determination against the odds and his human spirit. What it didn’t add was that he also appears to be made of Teflon.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments