Why are we so bad at calculating risk?

If you buy a lottery ticket every week, you’re more likely to be murdered in your home by a stranger than win the jackpot – but that doesn’t stop you buying the ticket. Chris Horrie looks at the psychology behind how we perceive risk in our daily lives

According to the Office for National Statistics, 12 in every million people in the UK were murdered in the past year, for which there is a complete set of non-Covid skewed data. And although past performance, as they say in adverts for share-tipping services, is not necessarily a guide to future performance, it means that, as a ball park figure, you would have to wait for more than 40,000 years to have a 50/50 coin-toss chance of being murdered on a particular day. You could probably at least double that waiting time if you live alone, since about half of all murders are carried out by close associates. For women, the clear majority of victims die at the hands of a partner. And yet the risk of death, or even serious injury, as a result of crime is overestimated by almost everyone. The ONS cites surveys which shows that more than 10 per cent of the population expect to be the victim of crime of some sort in the next year, but that on average about a third of 1 per cent of the population is affected in this way. The perception of risk is 30 times greater than the reality, at least in terms of reported crime.

In contrast, the risk of death as a result of nuclear war is ever present, and recently has increased according to the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists to the point where we are 100 seconds to midnight on their doomsday clock. The doomsday clock is not a clock, it is a numerical scale from zero to 43,200 where zero is OK and 43,200 is the end of the world. We are now at 43,100 and counting. This is not the same sort of data as the piles of legally verified death certificates collated by nitpicky bureaucrats to produce the crime numbers. But it is based on a valid analysis by people who seem to know what they are talking about.

In January 2020 the scientists increased their risk assessment because of the planned expansion of nuclear weapons programmes by several countries including the US and UK. But far from scaring the living daylights out of people, the announcement (and the underlying facts about nuclear proliferation and waves of new conflict triggers around the world) was widely ignored. The news was swamped by Meghan Markle’s withdrawal from royal duties and, on the risk assessment front, the death of two skiers in an avalanche in a Californian mountain resort.

Part of the reason for this studied indifference might have been the clock gimmick itself. The scientists’ accompanying statement concluded by saying: “It’s 100 seconds to midnight. Wake up!” At that time of night it is highly inappropriate to wake up. People want to fall asleep at midnight, if they have not already done so. And that is precisely what everyone did, ignoring the warning entirely and hitting the doomsday snooze button.

The coronavirus pandemic seems to have highlighted two related problems of public perception that have become more urgent as, ironically, scientific understanding of the world has been increasing at an accelerating rate. The first is the difficulty people have in assessing risk outside their immediate area of expertise; and the second is a failure to understand the nature of probability theory and scientific method when it is applied to risk, especially in the field of public health.

This does not seem surprising given the way everything gets relentlessly more complicated and out of our personal control and at a rapidly accelerating rate. There was a time when I used a pen and a piece of paper to write. I could more or less explain how these things worked, and could even make myself a functional substitute by regressing to a quill made out of a pigeon feather and ink made out of soot and water. I now write using a mobile phone and I do not have even the slightest idea of how any of it works. If my phone goes south during civilisational collapse, or even a temporary power cut, I can hardly regress to using two tin cans and a piece of string. Like so many things my phone appears to use a kind of magic, or might as well do so.

Evidence of inability to calculate the likelihood of various life-changing events, with a massive bias towards optimism, abounds. The odds of winning the jackpot in the UK national lottery are about 45 million to one, and the game costs £2.50 to enter. If you bought 45 million tickets you would, all other things being equal, be certain of winning all of the £14m jackpot. But you would have spent £112.5m on tickets in the process, resulting in a loss just short of £100m. As a rational proposition, buying a jackpot ticket amounts to buying £5 notes from an eager vendor who is selling them for £40 each. Even when you take all the runner-up prizes into account, the lottery operator Camelot admits that for every pound you spend on tickets you can expect to win only 50p. Camelot says a 50p loss is not a lot to pay for the fun of being involved in the TV show, and amounts to a regular charitable donation anyway. But another way of looking at this is that if you bought a lottery ticket every week, you would have to wait 23 million years to have even a 50:50 chance of winning the jackpot by which time you would have been murdered in your home by a total stranger (see above). So why bother?

According to experts at Harvard University there is a profound cognitive bias in favour of positive events like lottery wins, which are believed to be far more likely to happen than predicted by probability. And so in any high street newsagent it is not uncommon to see somebody buying a lottery ticket with the one hand, and a packet of cigarettes with the other. The odds of dying or getting serious lung disease from smoking round out at about one in 10. Some peer-reviewed studies put the likelihood of smokers developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at 50:50.

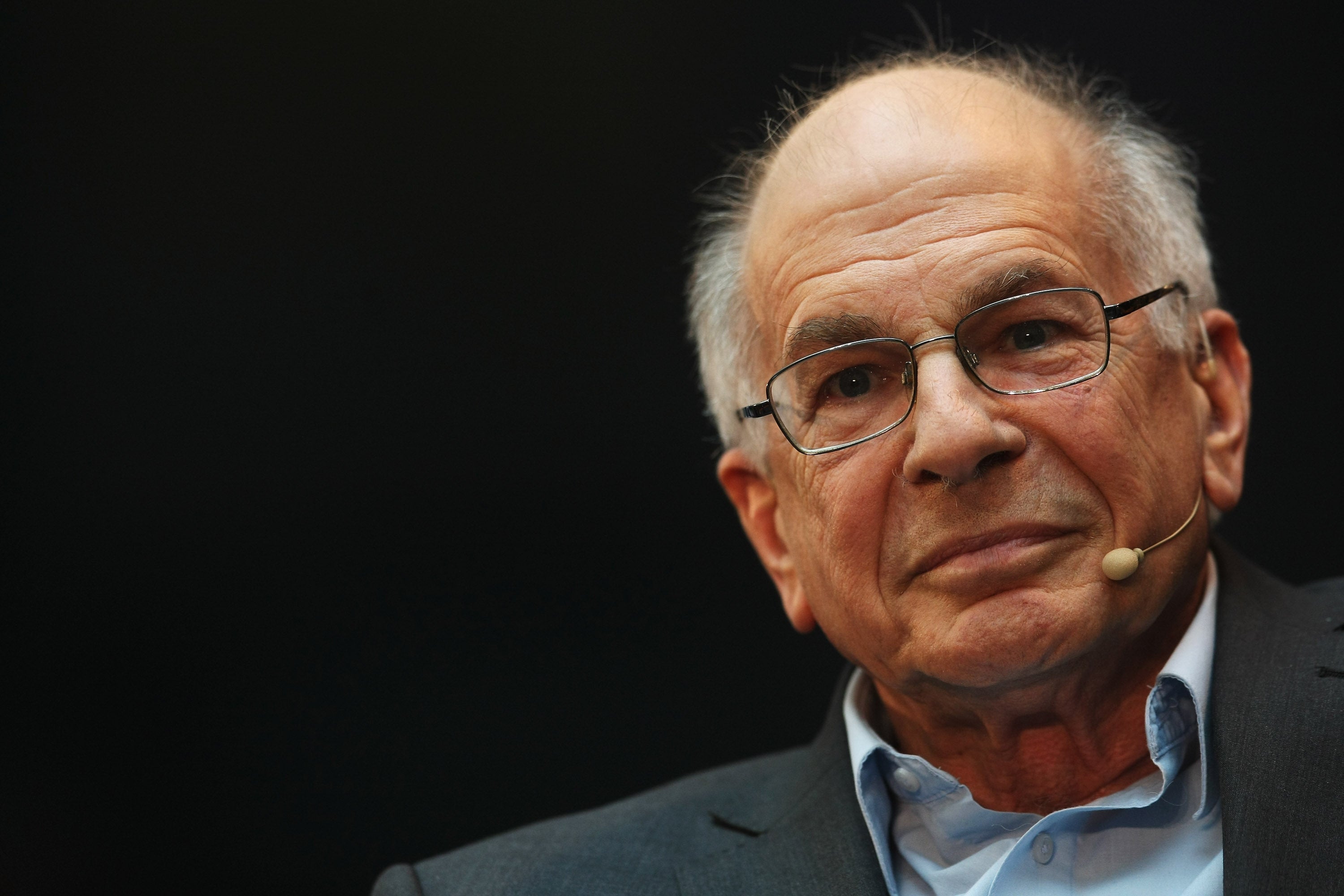

The Princeton economist Daniel Kahneman pioneered much of the research into cognitive biases, or prejudices, which determine the way we perceive personal advantage or risk, as a way of predicting economic behaviour. He found that subjective assessment of what would benefit people and what would harm them to be wildly out of touch with reality. This was big news for economists who used to think that people left to their own devices would accurately work out how to maximise their own wellbeing. In 2002, Kahneman won the Noble Prize for his theory of “fast-slow thinking”, which now forms the basis of understanding of how the public perceives risk.

Kahneman and his followers derive their economics from evolutionary biology, neurology and behavioural psychology. Humans face an immensely dangerous set of threats in the external environment. The avoidance of death is far more important than any sort of gain, pleasure or advancement in the evolutionary process and this is true for all conscious species. And so our first response to almost any external stimuli is alertness to danger or what we think of as fear. This is the “fast” part of our thinking, also caked by Kahneman as “System One” thinking. And it is not dumb. It is extremely useful.

When the external stimuli is unfamiliar or threatening – like the proverbial bump in the middle of the night – System One will automatically focus all our attention on the potential threat and will flood the body with adrenalin ready for an immediate fight or flight. Then almost immediately “Slow” or “System Two” thinking will kick in. In a System Two state the adrenalin level drops sharply and a person is able to analyse what is going and even apply rules, such as those of probability theory. System Two is a more self-aware type of thinking, governed by rationality, and pattern-seeking and requires significant mental effort. You will start to think of all the non-threatening reasons why you might hear an unexplained noise at night, then remember all the other times you had such an experience and reason that it is extremely unlikely for anyone to come to harm in those circumstances.

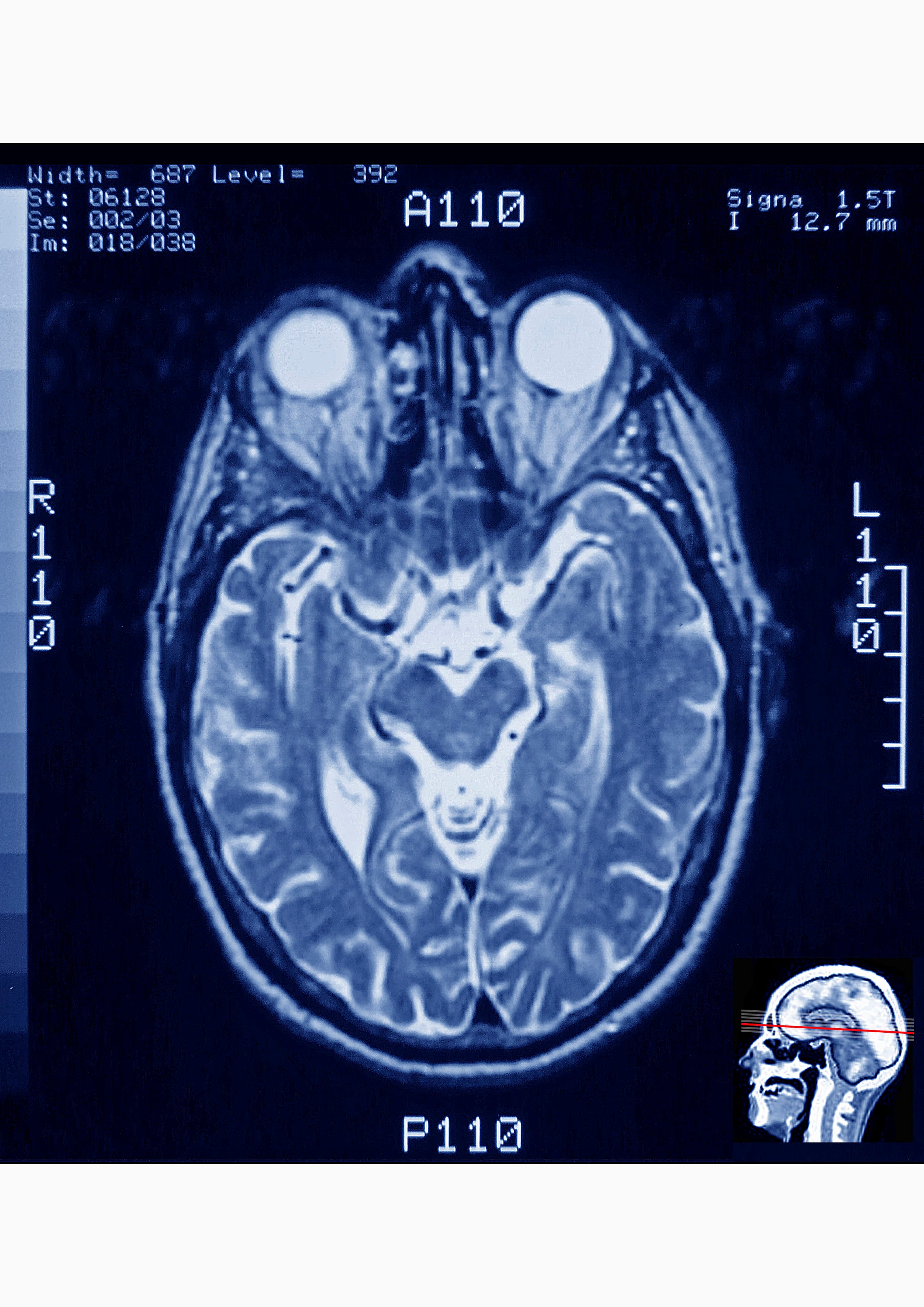

Kahneman’s behavioural theories map neatly onto what is known about the physical structure of the brain and how it evolved. System One thinking is associated with activity in two almond shaped areas near the brainstem called the amygdala, which evolved at the time our ancestors were reptiles. It monitors intrusion into personal space and control the fight or flight response. When this part of the brain is dominant, we will have the outlook of a reptile – terrified by the presence of an unfamiliar slightly larger reptile a few inches away from us, but entirely unaware of, and unconcerned for instance, about a gigantic pile of radioactive waste located just a few feet away.

Our ancient ancestors on the savannah faced the constant threat of predation. Ninety-nine times out of 100 a sudden slight rustle in the long grass would just be a gust of win. But one time in 100 would have been a predator. Fearing every unexplained snapping of a twig might be an uncomfortable way to live but as an evolutionary behaviour it is a small price to pay to be fully focused when the rustle turns out to be the stealthy approach of a leopard or a hostile hunter from another tribe. Today this hangover from our evolutionary past can be a problem. It causes us to overestimate the danger of some things which basically now never happen – such as being murdered by a total stranger or mauled by a herd of marauding animals; and underestimate dangers now all too common but unknown to our ancestors, such as driving a car while watching a football match on a mobile phone, sudden death from vape-exacerbated lung disease or being attacked with nuclear weapons.

Over the top of this “reptile” brain humans evolved a mammalian brain concerned with nurturing and protecting the young. This part of the brain extends the reptilian instinct for self-preservation to concern for the wellbeing of our children and close family members, which is one reason most parents experience paralysing and irrational fears about the safety of their children, but give barely a hoot about the death of other people’s children or family members in a distant war or famine.

Finally humans have evolved a thin and precarious layer on top of the brain called the cerebral cortex which enables language, human-type consciousness, imagination and foresight – including the ability to imagine and assess threats with System Two thinking. The cerebellum can easily be overwhelmed and shut down by chemicals pumped out by the reptile brain. So if, for example, you notice an unusual shadow, or the sound of footsteps behind you at night, you will stop thinking about abstractions such as rising sea levels or asteroid impacts, and start thinking that you are being pursued by an insane axe murderer intent on killing you and eating you and your children. This condition is known as an “amygdala hijack” – a term coined by Daniel Goleman in his 1996 book Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ.

This involuntary but evolutionarily advantageous tendency to fear an assassin or a nest of deadly snakes around every darkened corner can lead to panic disorders and is a possible explanation, at least in part, for otherwise mysterious psychiatric conditions such as agoraphobia – the irrational fear of the outdoors – especially if the amygdala is overactive or its hormonal control system is damaged or malnourished in some way. About one in five people in the UK suffer from panic disorders including agoraphobia. The usual treatment is cognitive behavioural therapy where the patient is encouraged to use a type System Two “slow” thinking to put their fears into context.

In addition to physical brain disorders, problematic overestimation of risk can be a perfectly healthy response. The psychologist Justin Barrett has defined this widespread problem as Hyperactive Agency Detection – the inherited tendency to ascribe intelligent action or purpose to natural phenomena where no such purpose or intelligence exists. The various theories, for which there is no evidence at all, that the coronavirus pandemic was caused by an intelligence ranging from a god who wishes to punish humanity, to the Chinese Communists who want to destroy the world economy for some reason, to drug companies who somehow want to profit from vaccines, even though most of the people in the developing world who will need the shots have no money to pay for them.

It is not as though we entirely ignore the dangers of modern technology such as chemical pollution or car smashes. It is just that we do not have the same sort of instinctual fast-thinking System One reaction we would have in the unlikely event of confronting a swarm of poisonous bees or being chased down the high street by a rampaging gorilla. The mass media provides another distorting filter by emphasising types of death and disaster which are dramatic but rare, such as exploding fertiliser storage tanks idiotically located in fireworks factories through to instances of men biting dogs. These things are, by their very nature, news. The Harvard Medical Journal reports several episodes of mass panic resulting from faulty risk perception. News that potassium iodide tablets could help prevent the development of radiation-induced throat cancer, for example, sparked panic buying of the supplement in pharmacies across the US in the wake of the 2010 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident, even though there was no increase in atmospheric radioactivity anywhere in the country and no danger whatsoever.

Back then, in the very early days of social media, there were plenty of people ready to cast doubt on the official version of events – possibly those who had cleared the shelves of Iodine tablets – and who were now feeling rather silly. But the panic soon subsided because the public tended to trust official sources of information, one of 14 specific filters affecting perception of risk in a widely use model developed by David Ropeik of Harvard School of Public Health.

According to Ropeik, people trust the authorities to provide information or warnings about a particular type of risk, they tend to be more afraid. Reputation is important. If an official source has overestimated danger in the past by, for example, repeatedly warning of the danger of invasion of neighbourhoods by ravenous wolves just as a wind-up, then when a real wolf threat emerges, the warnings will be ignored. This problem afflicts many of the ecological, green or anti-nuclear campaigners who have been repeatedly warning of extreme danger for several generations. People adopt the attitude that although they have lately fallen off the top of an 80 storey skyscraper they have not yet hit the ground, so why not lie for the moment and let the future take care of itself. Widespread scepticism about official warnings may well date back to the cold war when the British government issued official advice called Protect and Survive, which suggested that you could mitigate the effect of nuclear attack by, in effect, staying obediently in the target zone and placing a paper bag over your head.

Imaginative or creative ability is, according to the model, a major cause of risk overestimation, especially when threats are invisible or hard to understand. Thus risks which are particularly horrifying but are extreme, such as being buried alive or being devoured from within by flesh eating insects, will be overestimated as threats when compared with risks arising from enjoyable amygdala-driven and thrill-based activities such as eating salty snacks, binge-drinking, drug taking, unsafe sex or wearing sunglasses while driving a racing car at night with the lights tuned off, or any combination of these things – in other words an average Saturday night out for the late Hunter S Thompson. Another evident example of the fun factor distorting risk perception arises from the rising popularity of US redneck activities in the wake of the hit Netflix series Tiger King, such as using dynamite to go fishing for catfish in a pond, crocodile wrestling and entering a cage containing a ravenous and enraged wild animal. The most high profile case of incorrect risk assessment has got to be that of Kelci Saffery, an attendant at Tiger King Joe Exotic’s theme park, as featured on Netflix. Saffrey’s fondness for petting tigers led to him underestimating the danger of being mauled, and losing one of his arms as a result.

Social attitudes and religious ideas also impact risk perception in a way that almost always needlessly increases danger, or turns risk perception upside down. Despite the decline of religious ideas of this sort in the UK, at least, sociologists have found them to have been replaced with a widespread superstitious belief in something like karma. It is a common idea now that if you have had bad luck in one aspect of life, then this shortens the odds on winning the national lottery because the cosmos owes you some good luck and needs to pay it. Sadly the exact opposite is the case in most instances. If you have been in a car accident, for example, you are more likely to be involved in a car accident again, as any insurance company knows.

And the same goes for pandemics. We may feel that we have had our fair share of misery from the current pandemic, and therefore fate, mother nature or the gods will not make us go through it all again and so we can relax. It is of course perfectly understandable that people would think that way. But it is a hell of a risk.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments