‘The love that dare not speak its name’: The show trial of Oscar Wilde

It had celebrities, aristocracy and clandestine affairs, shocking twists and rumours of murky underworld dealings. No wonder it’s still so captivating today, writes Olivia Campbell

Few cultural moments still manage to satiate our guilty pleasure for drama and controversy today than the trials of Oscar Wilde. While it’s important to remember it for what it really was – the public persecution of a queer man for the simple “crime” of loving other men – it’s hard not to see why it captivated and scandalised Victorian society.

Today marks the 125th anniversary of Wilde’s sentencing for “gross indecency”, the unjust result of the poet’s attempt to protect himself from libel that ended up destroying his life. It’s a common misconception that Wilde was “put on trial for homosexuality” (the poet himself brought on the legal proceedings), but salacious details about his private life soon caused his downfall.

It began with five badly scrawled words: “For Oscar Wilde posing Somdomite [sic].” It was a calling card left for the playwright at the Albemarle Club by John Sholto Douglas, the ninth marquess of Queensberry, who is now most well-known for creating the rules of modern boxing. It set in motion a chain of events that are still notorious today.

“Before the trial, the general public didn’t really know that Wilde was queer. There had been rumours, but that’s all they were,” says Professor Dominic Janes, author of Oscar Wilde Prefigured: Queer Fashioning and British Caricature, 1750-1900. “Around the early 1890s, he began taking more risks, writing literature that was full of metaphors and euphemisms concerning same-sex desire. He was also hanging out with other people who were not thought respectable.

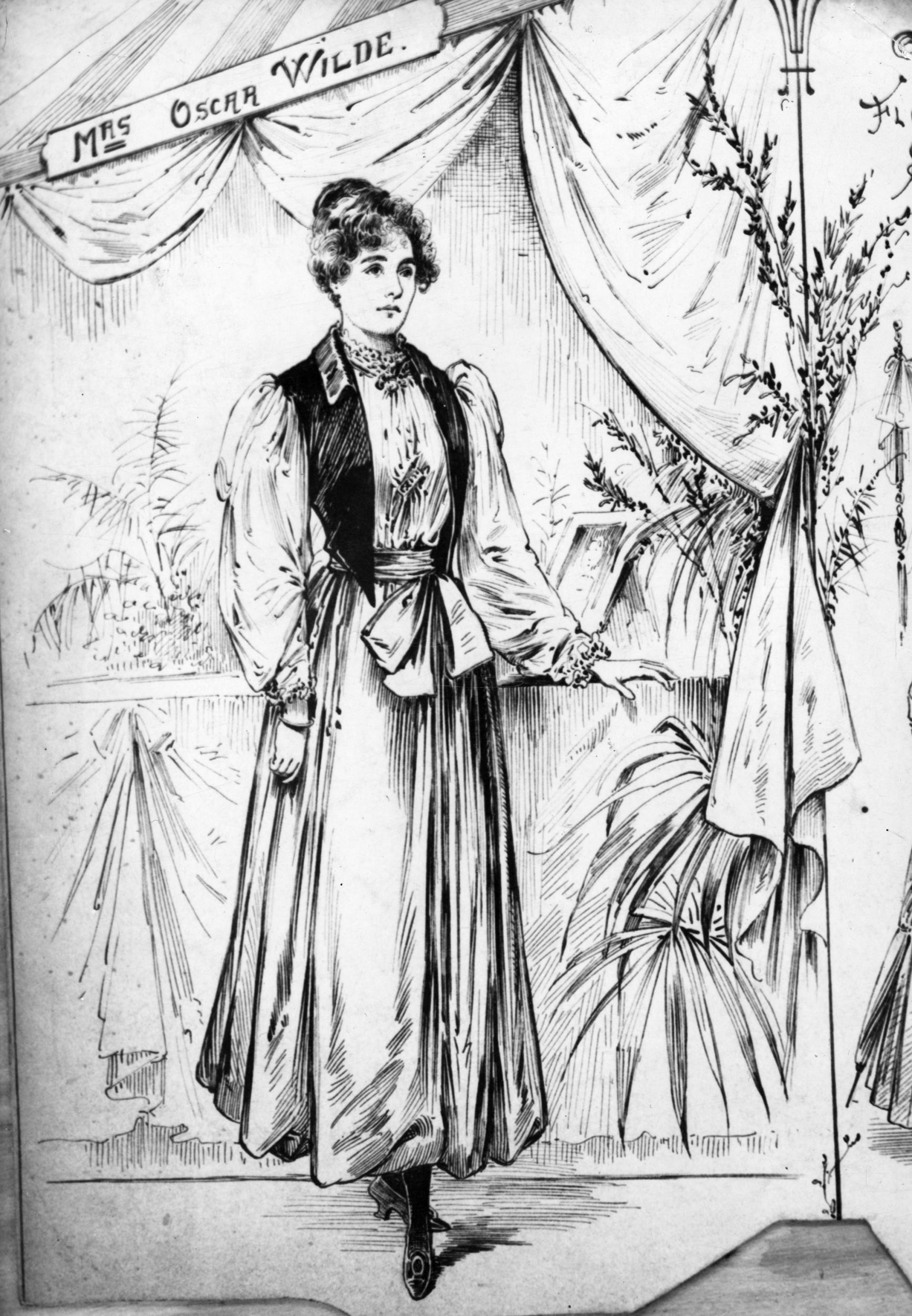

“The rumours did die down after his marriage to Constance Lloyd [who he would have two sons with], but they did start up again when he was away from his wife, spending a lot of time out in high society. Wilde had a whole range of male relationships, some of them simply friendships, while others were sexual. He also had casual encounters.”

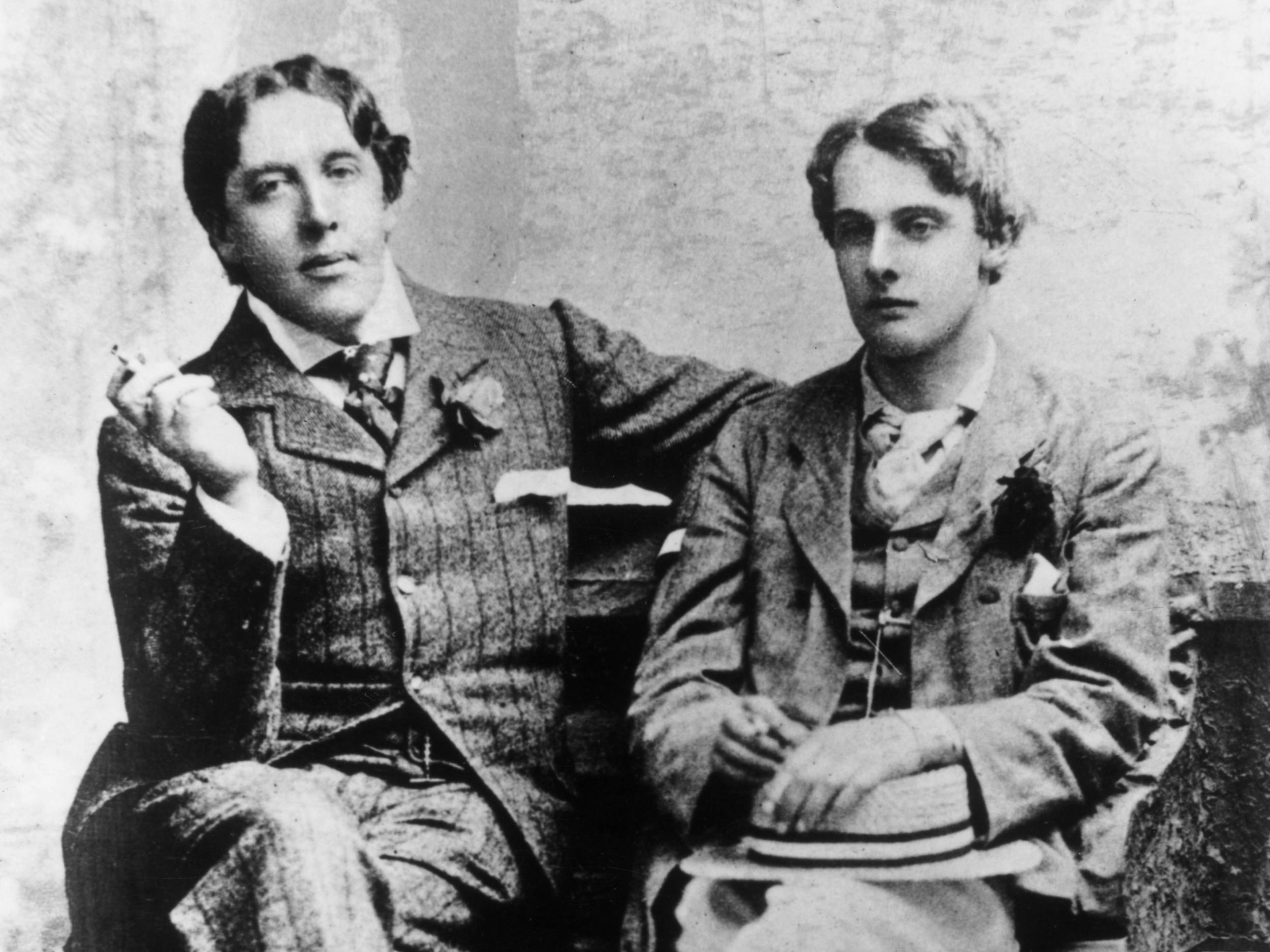

Wilde’s clandestine affair with Lord Alfred Douglas, son of the marquess, would prove to be the poet’s undoing. The two secret lovers met at a tea party in 1891 and soon became inseparable, even though Douglas, aged 21, was 16 years his junior.

“Wilde totally fell in love with Bosie [the nickname for Lord Alfred] for his good looks and personal charm,” says Vanessa Heron, secretary of the Oscar Wilde Society. “The fact that he was a poet and a lord also helped. Wilde liked mixing with aristocracy, and Bosie had the handsome Greek looks, the breeding, and as it transpired, the same taste for drinking, dining and exploring London’s gay underworld.”

Letters sent to Lord Alfred (which would eventually be used as evidence) reveal a man infatuated with his lover, his literary muse – his very own Dorian Gray, some cynics would say. “It is a marvel that those rose-leaf lips of yours should be made no less for the madness of music and song than for the madness of kissing,” wrote Wilde in 1893. “Your slim gilt soul walks between passion and poetry.”

Queensberry feared a relationship between the two and set out, rather obsessively, to end it. He began a sustained campaign of harassment, threatening to beat up hotel staff if he discovered Wilde and his son together on their premises. He even turned up at Wilde’s family home in Chelsea, intending to attack the poet and only leaving after Wilde threatened to shoot him.

However, it was the aforementioned calling card that would prove to be the final straw. In Victorian society, being labelled a “sodomite”, could spell ruin and disgrace.

“Britain had some of the strongest anti-homosexuality laws in Europe,” explains Janes. “The death penalty was in place until 1861 [the last execution took place in 1835]. In general, one of the main images of what we’d call a gay or queer man was a sexual predator of younger men. Many people would have also been informed by religious arguments from the Old Testament.”

Indeed, Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, commonly known as the Labouchere Amendment, made “gross indecency” a crime in the UK. What gross indecency referred to was unclear, so in practice, it meant that any homosexual behaviour could be prosecuted by law.

Wilde’s hedonistic life he had built up for himself was now in danger of collapsing and it was time to act. In a letter to Lord Alfred, Wilde wrote: “I don’t see anything now but a criminal prosecution. My whole life seems ruined by this man. The tower of ivory is assailed by the foul thing. On the sand is my life split. I don’t know what to do.”

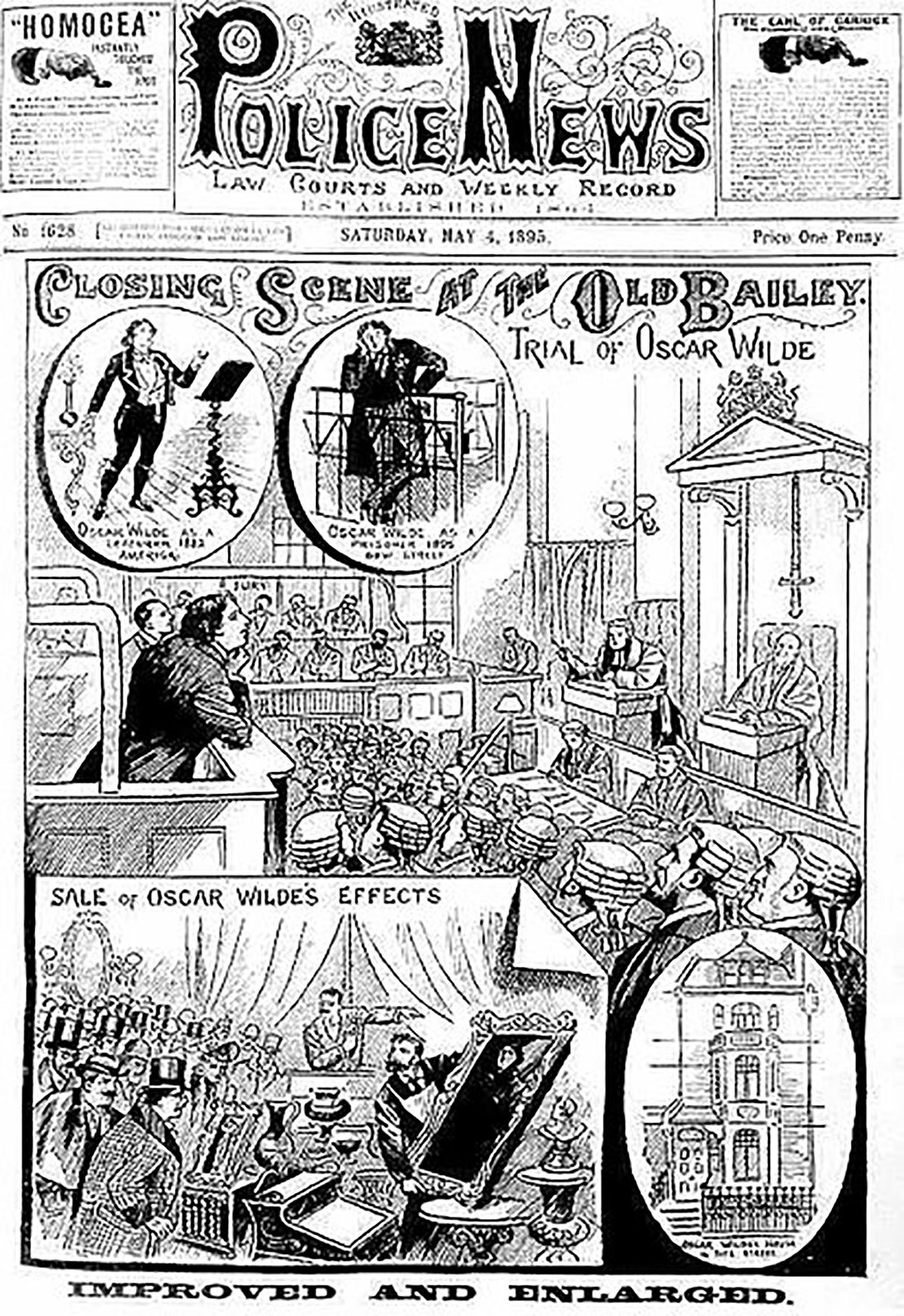

Soon, Wilde’s lawyer took out a warrant for criminal libel against Queensberry and he was arrested on 2 March. Libel laws at the time meant that the onus was on Queensberry to provide tangible evidence that Wilde had indeed engaged in sexual activity with men. On 26 April 1895, the doors of the Old Bailey opened and what would turn into three trials, each more damning than the last, began in earnest.

Almost immediately, renewed rumour and gossip began circulating about Wilde, whose string of successful plays earlier that year had catapulted his fame to new heights. The tabloids scrambled to print information about the trial, ready to be devoured by a public hungry for scandal. Friends from various literary circles, such as Frank Harris and George Bernard Shaw, advised against pursuing the case and instead suggested he flee to France – a much more liberal place for queer people. The playwright, however, was determined to see it through.

Ever the sartorial dandy, Wilde wore a fashionable coat with a flower in his buttonhole. Right off the bat, Sir Edward Clarke, Wilde’s lawyer, tried to take the sting out of some of the evidence that would be used against the poet. He read out letters sent to Douglas, framing them as a product of Wilde’s poetic mind with “no relation whatsoever to hateful and repulsive suggestions”.

Wilde was initially able to spar with ease, using his wit to reply to the questioning. He even successfully defended himself when Edward Carson, lawyer for Queensberry and an old rival of Wilde, attempted to question the moral content of the poet’s work. When asked if The Picture of Dorian Gray could be considered a “perverted novel”, Wilde retorted: “That could only be to brutes and illiterates. The views of Philistines on art are incalculably stupid.”

However, for all of Wilde’s confidence, there was one fatal flaw in his belief that he would win – everything Queensberry had accused him of was true. Cracks started to show in Wilde’s defence, particularly when Carson began probing his many friendships with lower-class men. Gasps were heard when the lawyer produced the lavish gifts Wilde had bestowed upon his muses. Wilde asserted they were merely good friends, even as Carson implied that they were not “intellectual treats” – but were in fact prostitutes.

The name Walter Grainger would also help the libel case unravel. Granger, a 16-year-old who had made the acquaintance of Wilde, had allegedly been kissed by the much-older poet. He denied doing it, claiming “he was a peculiarly plain boy” and was “unfortunately, extremely ugly”.

Carson seized on this, asking him to clarify. Wilde, not so flippant anymore, replied: “You sting me and insult me and try to unnerve me; and at times one says things flippantly when one ought to speak more seriously.”

However, the final nail in the coffin was still to come. Unbeknownst to Wilde and his legal team, Queensberry had spent a considerable amount of money on a private investigator who’d managed to dig up evidence of Wilde’s dealings with the Victorian underworld. In his opening speech the following day, Carson announced that he intended to call a number of young men, many of whom were London-based prostitutes, to the witness box. They all claimed to have had sexual encounters with Wilde. Much of the testimony was explicit and helped the prosecution portray Wilde as a degenerate older man preying on younger innocents.

Wilde was forced to withdraw his case. The first trial was a disaster of epic proportions and the second was just around the corner.

But why was Wilde so determined to pursue the trial in the first place? “Basically, rich people loved suing each other in the 19th century. You would no longer challenge a man to a duel, but you could take him to court,” says Janes. “There’s definitely an element of trying to defend his honour.

“I also think that Wilde was pressured by Lord Alfred. He hated his father and basically, reading between the lines, may have told Wilde, “if you want to keep my love, go after my father”. There’s definitely an element of emotional blackmail. I also think there’s an element of Wilde believing that it’s the right of a gentleman to live his own life however he chooses without “vulgar associations” being thrown at him.

“It was definitely a gamble, but he had a big personality that would allow him to pursue such a thing. He thought ‘if I win this case everyone else is going to be terrified of being defeated in court. They’ll shut up and I’ll get away with this.’”

Heron agrees: “Wilde was being followed around London, routinely being threatened. His life was being made a misery by Queensberry and his increasingly public scenes. He felt he had to do something.”

Queensberry, not content with winning the case and the fact that Wilde was going to go bankrupt after covering the legal fees, was determined to finish what he started. The evidence of Wilde’s activities were taken to the House of Commons, where an order for his immediate arrest on charges of sodomy and gross indecency was made.

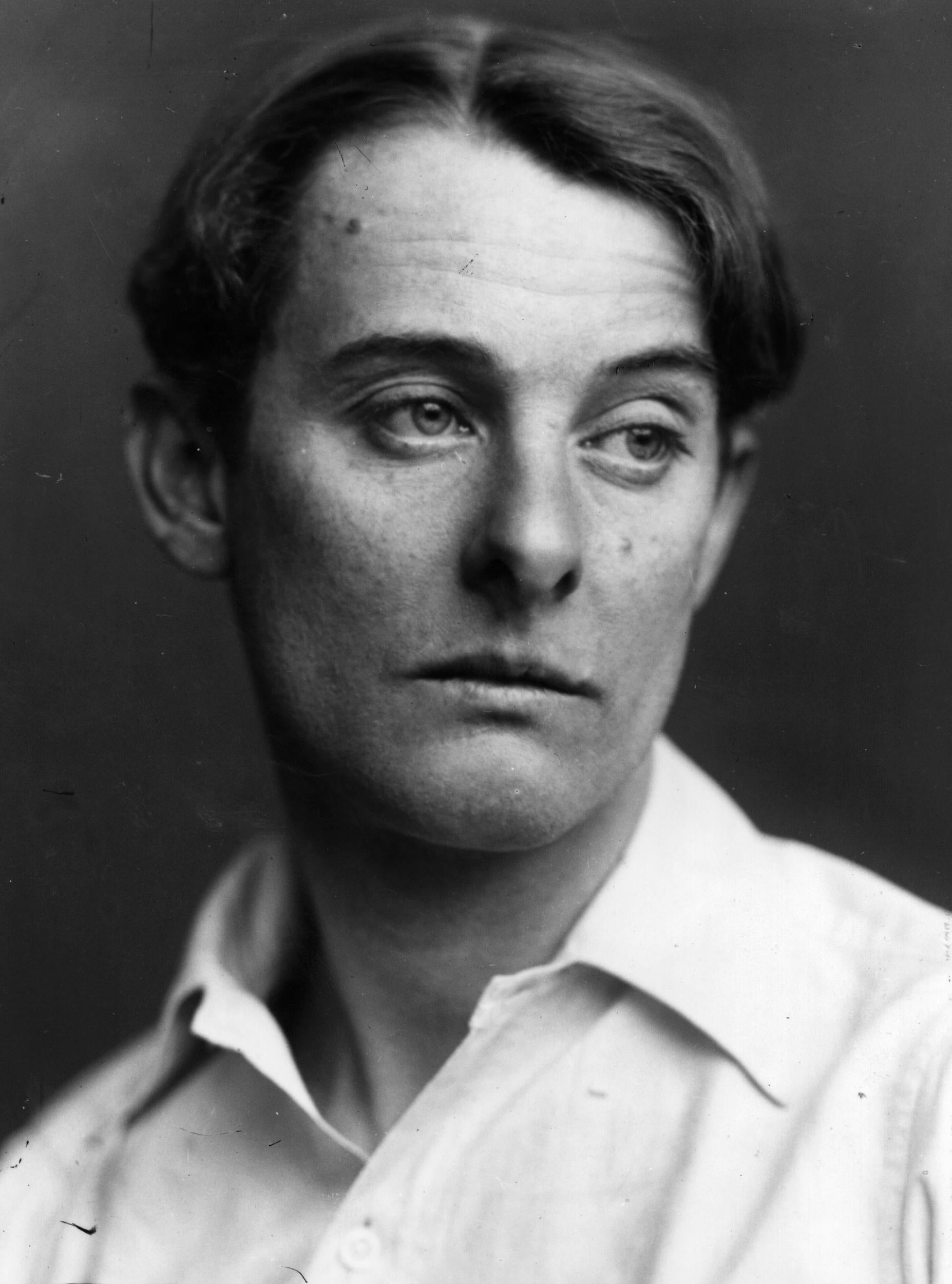

After the failure of the libel trial, Wilde slipped into a state of depression and inaction, says Janes. At the Cadogan Hotel, the poet refused to decide about whether he was going to try to flee to Paris or stay and face the music. All he could do was say that “the last train had gone” and ”it was too late”. When the police came knocking, they found a dejected Wilde sitting moodily in his chair, drinking cocktails. He was arrested and imprisoned at Holloway.

As an almost hysterical fascination descended on Victorian society, the second trial began. On 26 April, Wilde arrived in court to a mob of onlookers, ready to face 25 counts of gross indecency and conspiracy to commit gross indecency – to which he pleaded not guilty. A parade of male witnesses came forth, describing in detail their encounters with the playwright. Outside of the court, the press had a field day.

When Wilde took to the stand, gone was the arrogance and certainty, in its place a subdued man who stood to lose everything. “Wilde’s eloquence didn’t work well when confronted with witness statements about his activities,” Janes says. “Things sort of just fell apart.”

Although a lot of evidence was revealed in the courtroom, one of the most memorable aspects of the trial was when the prosecution questioned a line from Lord Douglas’ 1894 poem “Two Loves”. “The love that dare not speak its name” had been interpreted as a euphemism for homosexuality. The prosecution wanted to use it as evidence, and Wilde seemingly confirmed it. He said it alluded to “the great affection of an elder for a younger man … It is that deep spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect.” This only reinforced the charges.

The jury was unable to reach a verdict, despite deliberating for hours. Wilde was released on bail, going into partial hiding to escape the press. He appeared to be realistic about his situation, writing to Douglas on the eve of his trial: “Tomorrow all will be over. If prison and dishonour be my destiny, think that my love for you and this idea, this still more divine belief, that you love me in return will sustain me in my unhappiness and will make me capable.”

It would not be until three weeks later, on 20 May, that the writer would finally meet his fate. For the third and final time, Wilde was back on trial. The jury found him guilty, he was convicted of the charges and sentenced to two years hard labour. Cries of “shame” erupted throughout the courtroom, with Wilde himself being drowned out by the racket.

The celebrity show trial had come to an end and Wilde was incarcerated on 25 May 1895 at Newgate Prison. He was subsequently moved between various institutions, before spending the remainder of his time at Reading Gaol – he was reportedly spat on and jeered at by a crowd on his way to the prison.

If his sentencing wasn’t cruel enough, the rest of his life would now unravel. Wilde’s fortune was drained to cover Queensberry’s legal fees. Creditors took possession of his home in Chelsea; his vast collection of books, art and other various treasures were sold at auction for a fraction of their original price; even his children’s toys were sold off.

The productions of The Importance of Being Earnest and An Ideal Husband were stopped altogether – the former was replaced by a play called The Triumph of the Philistines, Heron says. Wilde’s family also suffered: his wife changed her surname and fled abroad with their children, forcing Wilde to give up his parenting rights. His two sons, Vyvyan and Cyril, had their names changed and were sent to separate schools, never seeing their father again.

“Merlin Holland, Oscar’s grandson, has often talked about how the story could have gone a completely different way. There are so many scenes and incidents, ironically like a play, where the outcome could have been different,” explains Heron.

“What if Wilde had just torn up the card left by Queensberry at the Albermarle Club? What if he’d left the UK after the collapse of the first trial and fled to France? What if he hadn’t sat drinking in the Cadogan Hotel where he was finally arrested but again had followed his friends’ advice? His story might have been one simply of disgrace and exile, not imprisonment.

“He might have had 20 or 30 more years of writing ahead of him and lived into the 1930s. Who knows what he might have written? Imagine Wilde in the late Twenties watching a Noel Coward play. I wonder what he’d have thought?”

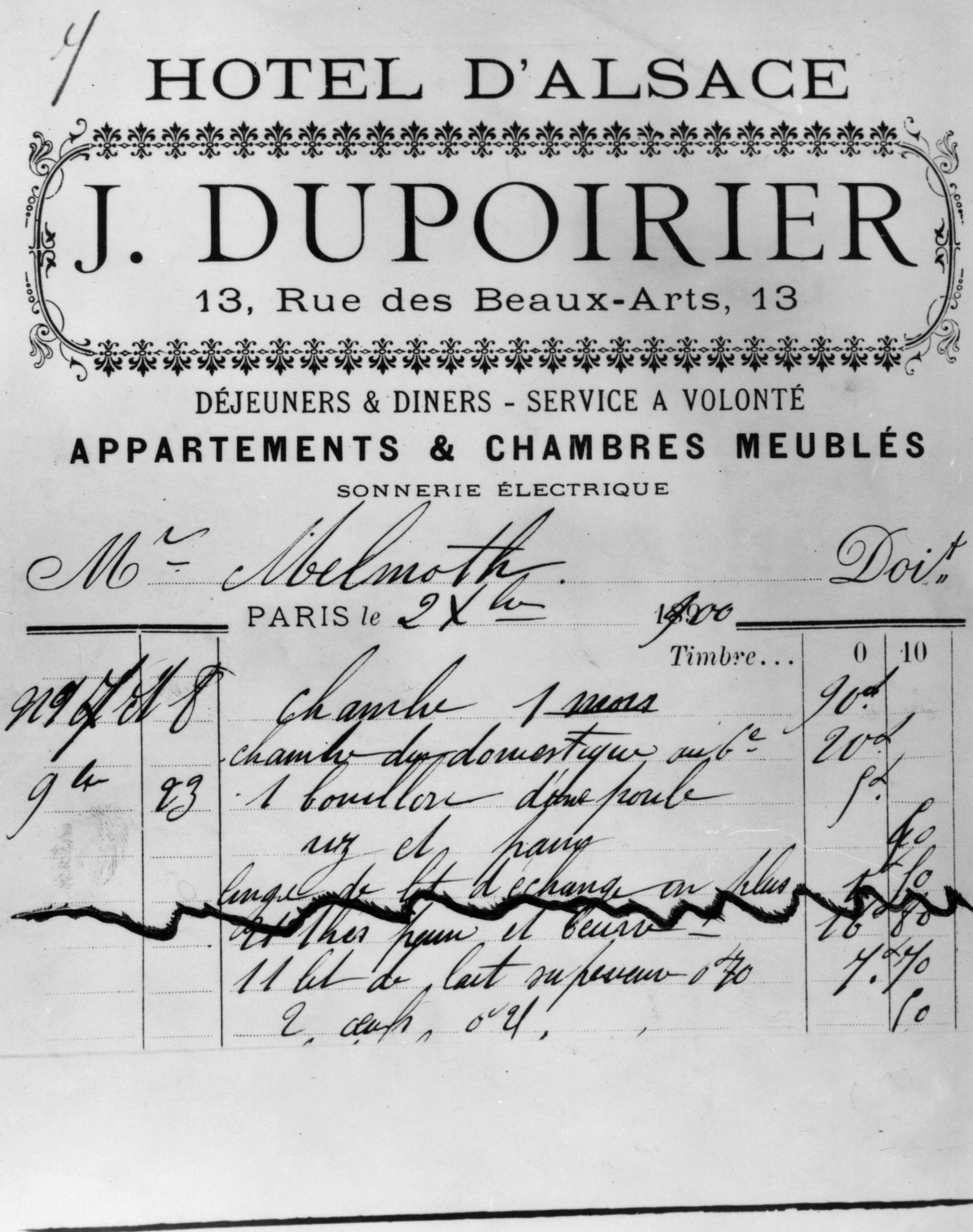

Wilde was released from prison in 1897, but his life was never the same again. Having suffered immensely during his time in incarceration, sustaining an injury that would later contribute to his death, the poet was never the same. He finally exiled himself to Paris, either staying with friends or in cheap accommodation – he never returned to the UK. Wilde spent his remaining years drinking too much, mainly absinthe, unable and unwilling to write, Heron explains. He did meet up with Lord Alfred, but their relationship was never the same.

If his sudden downfall wasn’t tragic enough, Wilde died alone in a hotel room in Paris in 1900. His last words were reportedly: “My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or other of us has got to go.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments