How Orbital changed Glastonbury – and my outlook – with their 1994 set

When David Barnett ventured to Somerset, little did he know he was about to become part of history when Orbital became the first dance act to headline a major stage

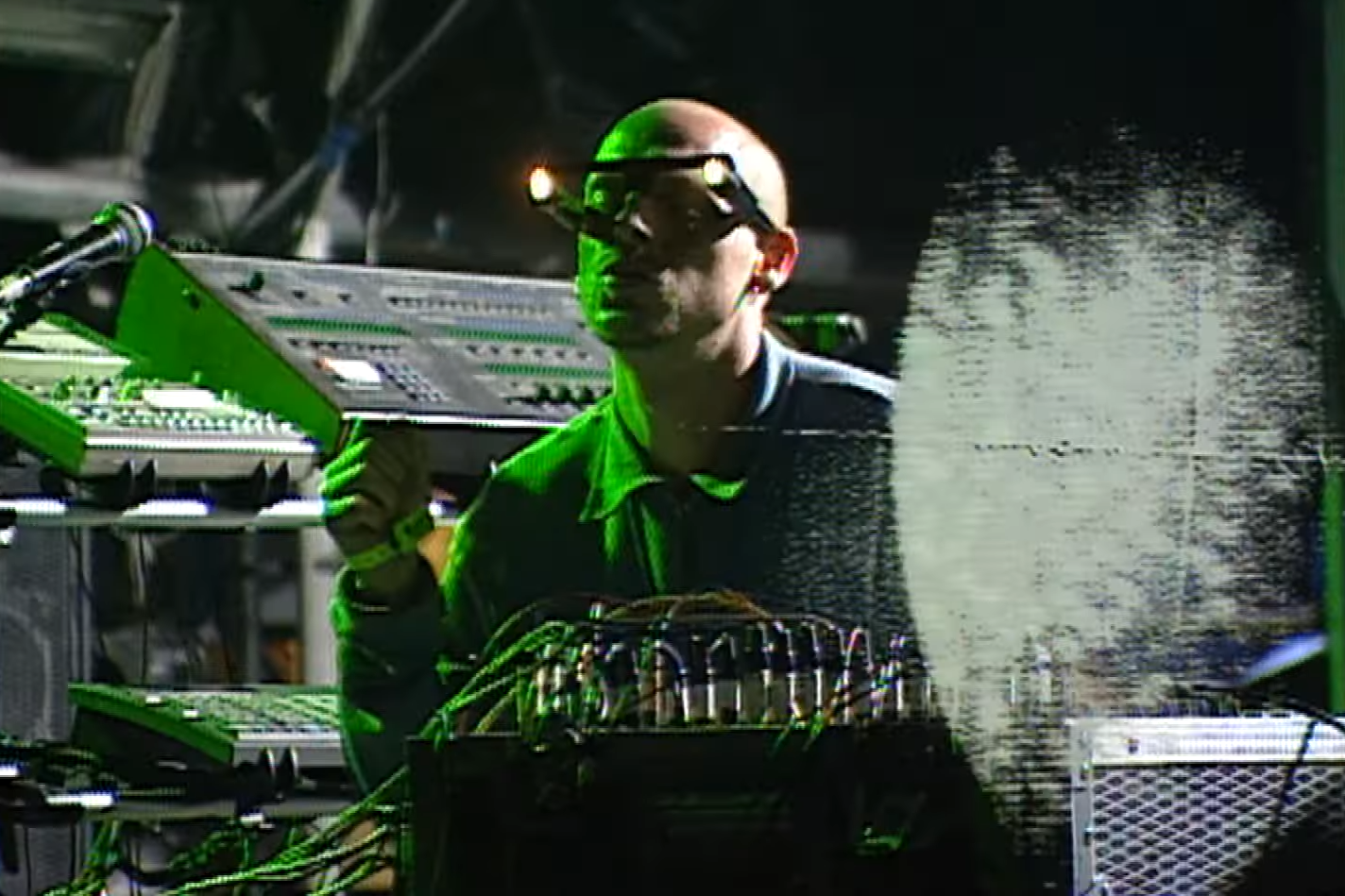

Saturday 25 June 1994. The Glastonbury Festival. The sun goes down and two blokes wearing glasses with little torches fixed to the sides walk onto the stage.

Do you know that history is being made when you’re living through it? That night we did. After two dozen years of predominantly guitar-based music, Glastonbury had put a dance act on to headline a major stage. Brothers Phil and Paul Hartnoll, aka Orbital, were an unknown quantity for both the majority of the Glasto crowd and the festival organisers. Nobody knew if what they did would work on a stage in a field in the middle of the countryside.

My memories of the performance are simultaneously dim and unreliable, yet shine with a razor-sharp clarity burned onto my cerebral cortex. I had to consult my partner-in-crime who was present on that balmy night almost 30 years ago to compare memories; they didn’t quite match up. I can clearly remember standing just to the left of what was then the NME Stage, a few rows out; he thinks we were further to the back. I remember waiting for Orbital to take to the darkened stage; he says we missed the opening track because I was vomiting with pre-match, potentially substance-induced, nerves behind the car while he laughed helplessly without knowing why.

You can’t trust your memories of Glastonbury. You just have to hack some path through the middle of what might have happened and let that be that.

But, anyway, at some point we stood in that ever-growing crowd, on that night, at that festival, and watched history being made; no, we took part in history being made. If you think that’s some old 90s acid casualty ravey-wavey bollocks, then of course it partly is, but it’s also partly true. The Glastonbury festival you will watch this weekend would not be what it is without that Orbital performance in 1994.

I was 24 then, the same age as the Glastonbury Festival itself, and pretty much a tie-dyed in the wool indie kid. Over the previous few years, I’d started drifting into the world of acid house and rave, but very much on the periphery. The previous year, after a night spent clubbing in Manchester, my mates and I had ended up at our friend’s house in Sale and slumped around the living room, watching music videos recorded on VHS off MTV or The Chart Show. Among the disjointed parade of images and sounds there was a video for a song called “Lush” by Orbital.

The video was just footage of people wandering around a car boot sale on a sunny Sunday morning. The music was sweeping and symphonic and orchestral and wholly instrumental and yet punchy and danceable and very, very British, as though someone had been pumped up full of amphetamines and threatened Ralph Vaughan Williams to invent a brand new classical techno sound to mark the death of the 20th century, there and then.

We sat up and watched it, and rewound the video and watched it again. Maybe 14 or 15 times.

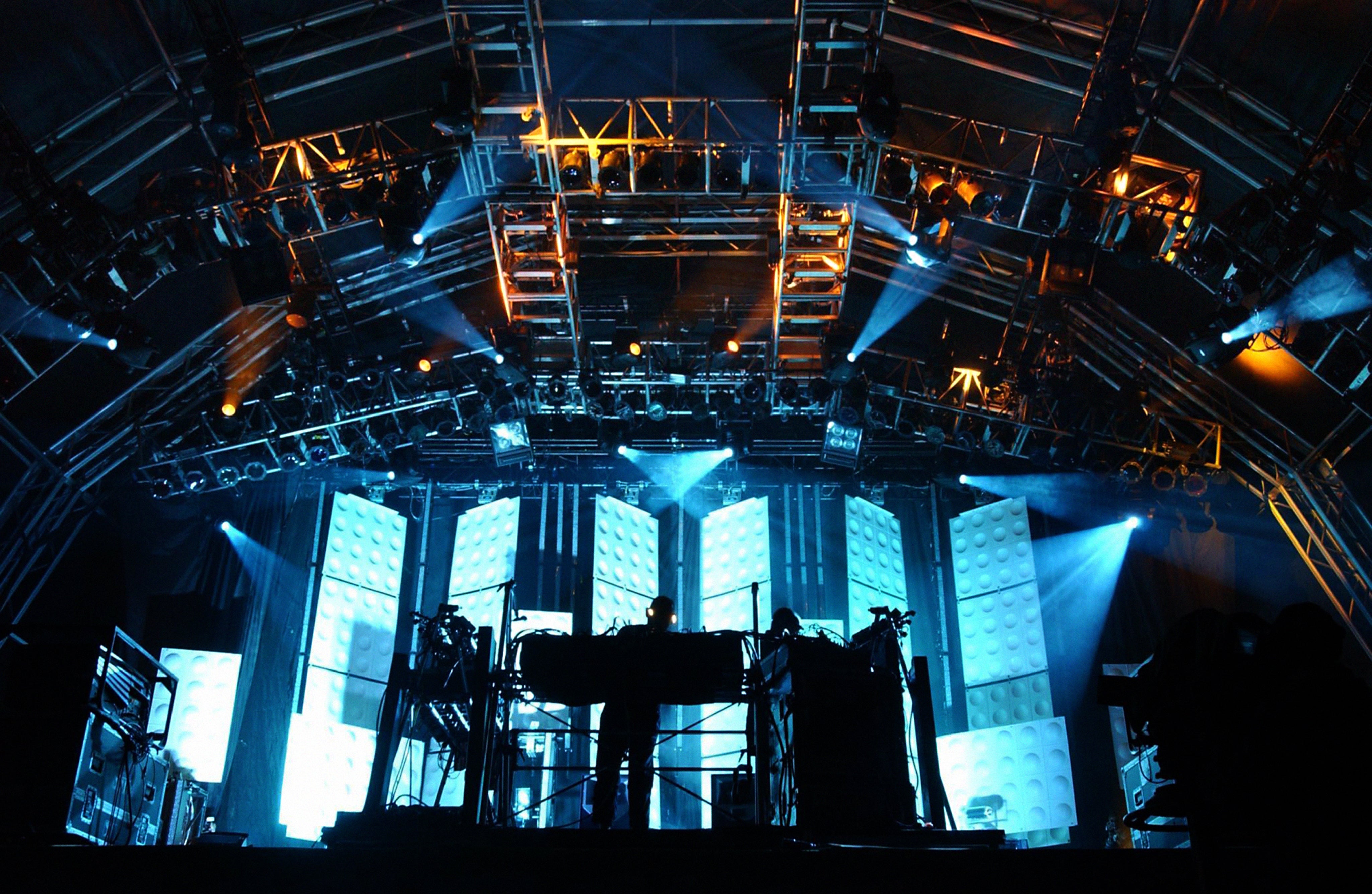

A year later, larks were ascending big time as, having patronised the itinerant purveyors of untested pharmaceuticals, the full force of Orbital hit us — and several thousand other festivalgoers – square in the mush. Nobody knew what Orbital were going to do or how it was going to play out in the Field of Dreams, but they came to find out. In my memory it’s like a scene from Close Encounters of the Third Kind when the spaceship finally lands and the people, stunned by what they are seeing, drift over to form a huge crowd to watch this visitation from another place. Life would never be the same again.

Orbital began life in the late 1980s, when Paul, the younger brother by four years, started experimenting with a four-track recorder. They’d started trying to make their own versions of disco songs, but then house music exploded and they knew they’d got their vocation. The first real track they recorded – under the stairs in their parents’ house in Orford, Kent – became their first single, Chime.

The tape found its way to DJ Jazzy M, who played it to a bunch of DJ mates in his Croydon record shop. They all wanted it for their DJ sets, but if course it didn’t exist other than on that tape. Jazzy M summoned the Hartnoll brothers and told them to make more of it. He put it out on his own label and pretty soon the major record labels came calling, among them one Pete Tong, legendary dance DJ who was at the time working as an A&R man for London Records.

“Chime” was released at the end of 1989, and it went ballistic, even earning the brothers a slot the following year on Top of the Pops.

Eavis was really complimentary. He said the light show was fantastic and the music was... tolerable. Which I thought was fantastic, and he says people enjoyed it and you can’t argue with that

“I was working in a pizza parlour at the time,” says Paul. “I was washing dishes. I’d done an art foundation year at Hastings Art College but didn’t have the qualifications to get on to a degree so I gave it up. I was living at my parents’ house which was empty because they were running a pub down the road so moved into that, which meant I could spend half the week making music and as much n noise as I liked.”

Phil, was a bricklayer by trade and was considering going out to do Voluntary Service Overseas, perhaps helping to build a school in Africa, but his partner fell pregnant and he decided to stay in the UK, and joined his brother in what would become Orbital (named after the M25).

Paul says, “From the moment Pete Tong signed us everything went mental.”

The fictions they inhabited for themselves as Orbital are that Paul is the slightly nerdy muso who arranges the songs while Phil is the evergreen, up-for-it raver. It’s both true and not. Certainly, they are playing according to type when I speak to them both separately by Zoom this week; Paul takes a break from working in his Brighton studio to take a walk on the seafront to talk to me while Phil is perched, shirtless and wearing huge headphones, on a stool at a beach bar in Greece where he’s on holiday.

“You’ve hit the nail on the head,” says Paul. “For you and for probably a lot of other people when we played Glastonbury in 1994 it was the first time the festival had showcased big, loud, banging dance music. It was a real watershed moment to bring that to Glastonbury and it showed people that dance music could be up there with all the rock music and stand up for itself on the big stage, and be fabulous and glorious like everything else.”

Festival founder, Michael Eavis, had taken a chance on Orbital, not knowing how it would go down. He admitted it wasn’t his kind of music at all, but he went down to join the crowd and watch the gig.

“Bless him, he might not like stuff but he’ll give it a try and that’s what keeps Glastonbury going,” Paul says. “Eavis was really complimentary. He said the light show was fantastic and the music was… tolerable. Which I thought was fantastic, and he says people enjoyed it and you can’t argue with that. I know he came and watched us that night in his spirit of adventure. He came and checked us out and the very next year they opened up the dance tent at Glastonbury. But we all thought, oh no, he’s going to ghettoise us and shove us all in the dance tent but he didn’t, he kept us all on the main stages and we even played on the Jazz World Stage at one point which was crazy. And the year after 1994 we played the main stage before Pulp.”

“I think Bjork was on before us,” says Phil from the Greek beach-side taverna. “Our agent sold it to them that we’d be the disco bit at the end, a nice little wind-down…” He laughs. “To be honest, we didn’t have a clue what would happen. We were like, my god, it’s just unbelievable that we’re here. Nobody apart from the fans really knew who we were or what we did.

“But afterwards, we got a lot of lovely, wonderful stories from people like you, people saying, ‘yeah, I used to be an indie person and didn’t get dance music at all until that moment at Glastonbury’. It seemed to be a bridge not just for Glastonbury to open the floodgates for electronic music but more importantly a bridge for individuals to get to electronic music, to not be so scared of it.”

It was a bridge I crossed that night, a rainbow bridge to the yellow brick road. A huge, ambitious parade of music that reached into your chest and squeezed your heart, accompanied by a dazzling light show and mind-bending visuals projected onto either side of the stage, while the brothers Hartnoll with their torch glasses bobbed their heads in the centre of the maelstrom like a pair of malevolent Jawas divested of their hessian robes. I vividly remember two huge animated hands opening and closing into fists as I shuffled my feet in the dry earth, not knowing whether to laugh or cry, an almost tangible sense of something undefinable welling up from the ever-growing crowd around me. Of course, that’s all just the bullshit drugs talking. But it was a pretty good show.

And Phil is right, people were a little scared of dance music, or at least, dubious about it. Some people thought it was just DJs playing records, and a lot of it was that. Phil says: “The music press at the time, NME and Melody Maker, weren’t covering dance music but they took us under their wing for some reason because although we were an electronic band we used to sample the Butthole Surfers and our influences were punk, indie, all sorts, and that was what we drew from.”

Because Orbital are a band, a proper, honest-to-goodness band. They might be surrounded by banks of analogue synthesisers and it might look like all they are doing is pressing buttons and twiddling knobs, but it’s actually a little more complicated than that.

It’s a constant ebb and flow, give and take, a balancing of the scales. If you look at the audience and you’re not sure that they’re digging something, you think – what can I do to jolly them up?

“Look, I don’t fib about this, I’m not up there on stage playing keyboards and guitars,” says Paul. “I have all this information ready to go in loops and clips. I play the guitar part once and then loop around. That’s the nature of what we do. But when we’re on stage, it’s as live as it can be because what we’re essentially doing is arranging the track right there on stage.”

Which is why, for anyone who’s followed Orbital over the past 30 years, every gig is different. Tracks such as “Lush”, “Belfast”, and “Chime” are never the same as they were on the last tour. They are often never the same as they were when played the night before.

Orbital take an intuitive approach to each gig. They will tailor each track to the audience, to the vibe, to the feeling they’re getting from them. “A song can last a minute or an hour.” says Phil. “There’s no tapes, it’s a studio up and running on the stage. We’ve got a mixing desk and even though people don’t know what’s going on they feel it, they know it’s raw and live even though they don’t understand why we’re pushing buttons and twiddling knobs. It’s the vibe that comes through the speakers, and people get that and that’s what we always wanted to do, really, even though they don’t know what the fuck we’re doing up there. Half the time we don’t!”

Phil, with typical, visceral verve, is being disingenuous there because while any Orbital performance is an evolving, fluid thing, the brothers know exactly what they’re doing. Paul tells me that “the songs are written and arranged in the studio but once we’re on stage we literally go back to the point before it’s arranged. There’s a muscle memory of what that track should broadly be, but each night it’s arranged again, depending on how we’re feeling. It’s a really nice, freeing way to play. If we’re on a 30-date tour we’d get bored doing the same thing day after day so we adapt it. We know how to do it, how it’s meant to be, but we play with it and see how we can do it differently. For example, last week we played two nights over a weekend, and the songs sounded different because the Saturday night audience had a different vibe from the Sunday night one.

“It’s a constant ebb and flow, give and take, a balancing of the scales. If you look at the audience and you’re not sure that they’re digging something, you think, what can I do to jolly them up? You can break it right down to the bass line, or pump it all up, and you just have to make an instinctive, non-verbal choice, go with your gut and see what happens. It’s a bit like being a tailor, holding a suit up to a customer and they go, nah, don’t like that, so you get another one and they say yeah, but it doesn’t quite fit, so you try something else. I mean, it’s not quite as clinical as that, it’s more intuitive.”

I’ve probably seen Orbital more times than I have any other band. The first time at Glastonbury in 1994, the last at Beat-Herder, a festival up in Lancashire, in 2012. I find it difficult to distinguish between the gigs — not in a bad way, just that they all seem to merge into one big, almost 20-year trip to some kind of dirty, fuzzy, techno-Narnia. Images bubble up occasionally. The Irish girl howling like a wolf to the band in Newcastle, her friend loudly confiding, “That’s the noise she makes when she orgasms.” Watching the band in Manchester, straight and sober, with a kind of clinical detachment and musical appreciation I’d not experienced before. The man with a propellor for a face in Brixton (actually some kind of head-mounted fan, which now I write the words sounds just as unlikely as having a propellor for a face). Sitting on the feet of the Angel of the North, wordlessly assessing the storming Orbital gig we’d just experienced. Time becomes a loop.

Orbital are very much a band you have to experience live. I have stacks of CDs and vinyl, of course, but the nature of what they do demands that whole, full-show experience. They’re not a band that has necessarily had a lot of success being played in clubs as part of DJ sets — their work is often too challenging and progressive and, isolated from a full show, doesn’t have the same impact.

“Dance music in of itself is very stylistic and has a very strong purpose,” Paul muses. “It’s got to be simple, got to be basic — I don’t mean that in a derogatory way — it’s almost… when you hear it, you’ve got to know what it is, even if you don’t know the track. It’s like folk music, you’ve got to be able to sing along instantly. And our music was never like that, we were always throwing curve balls. It isn’t necessarily comfortable music on the dance floor.

Phil adds: “That’s why, after Glastonbury in 1994, we realised we really enjoyed being a festival band. We fit in better with the festival crowd than in the clubs because, you know, we’ve got a song called ‘Satan’ and we used to clear the dance floor with that back in the 90s. We are more of a band in the sense that what we play is not in a constant groove, and it’s a bit challenging for some of the dance floors. The good thing about festivals is that we’re preaching to the non-converted as well, we’re trying to win people over. It suits us, I think.”

Glastonbury 1994 was the biggest crowd they’d ever played. Was it daunting? “Not for me, I don’t think,” says Phil. “The adrenaline was pumping so much all I was bothered about was the audience enjoying themselves and that doesn’t matter if it’s eight people or 80,000. But it was insane when we finished that set.

“When we were little boys we used to do this silly dance that I made up, before we got into the bath. It’s called the ‘Chish-ta-bum Song’. We’d just poke our arses out and go ‘Chish-ta-bum! Chis-ta-bum! Chish-ta-bum!’ Then jump in the bath. When we came off after Glastonbury I said to Paul come on, let’s do the dance. And we did. Never done it since!”

It’s a fair bet that had Michael Eavis not taken a gamble on putting Orbital on the NME Stage in 1994, the Glastonbury Festival might never have diversified away from just rock music. No Jay-Z in 2008, no Stormzy in 2019, no Chemical Brothers, just confirmed to be playing Friday night this year.

Orbital’s new album ‘30 Something’ is released 15 July via London Records and they will headline Kaleidoscope Festival on 23 July and Stowaway Festival, 19-21 August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments