A fitting song of struggle and resistance to celebrate Daunte’s life

The decision to sing ‘Oh Freedom’ at the funeral of Daunte Wright was an act of protest and defiance, observes Andrew Buncombe

It gets going about 20 minutes into the service to honour Daunte Wright – the young man’s face leaping from a screen on the stage and the bright stabs of an organ’s swirl filling the church hall. People are still making their way in, and finding a seat.

“Oh freedom. Oh freedom. Oh freedom over me.

“And before I be a slave, I’ll be buried in my grave.

“And go home to my Lord and be free.”

The singer is Greg Drumwright, a visitor from North Carolina, and the song is “Oh Freedom”, a piece of gospel music that traces its history to the time of slavery. It was later sung during the civil rights era by the likes of Joan Baez and Pete Seeger, and black activists and musicians such as Harry Belafonte. The decision to perform it at the service for the young unarmed African American man killed by police in Brooklyn Center, a suburb north of Minneapolis, is very much considered. For while the service is an attempt to tell the world more about the life cut short after a police traffic stop turned into a tragedy, it is also an act of protest and defiance.

Drumwright, an activist and preacher from Greensboro, has been in lawyer Ben Crump’s team as it sat through the trial of Derek Chauvin, the former Minneapolis police officer charged with murdering George Floyd. As the trial reached its conclusion, Daunte Wright was killed, triggering loud protests, and again highlighting the vulnerability of unarmed black people to the police’s use of deadly force.

As he sought to comfort the young man’s parents, as part of Crump’s extended network, 41-year-old Drumwright, who was a musician before becoming a pastor, was asked to select and perform a song at the service at the Shiloh Temple International Ministries in North Minneapolis.

Chauvin, 45, was found guilty on all three charges: second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. The jury deliberated for less than 10 hours. Joe Biden described the verdict as potentially marking a “giant step forward in the march toward justice in America”, but also acknowledged it was a “much too rare” a moment for black America.

It was a murder in the full light of day, and it ripped the blinders off for the whole world to see ... it took all of that for the judicial system to deliver basic accountability

“It was a murder in the full light of day, and it ripped the blinders off for the whole world to see,” the president said. “For so many, it feels like it took all of that for the judicial system to deliver a just – just basic accountability.”

A week before the jury went out to consider its verdict, Brooklyn Center police officer Kim Potter was charged with unintentional manslaughter for the shooting of the young father, having purportedly pulled out her gun rather than her Taser in what her boss said was an accident.

Drumwright tells The Independent much was weighing on him as he made the selection that mourners would hear. “It was a song that I chose to perform, because it put me in a space where black folks have endured so much trauma post-slavery,” he says.

“When I think of Daunte, in his confusion and his anxiety for what was happening to him, in that moment, when I seen him jump in his car, I felt like that was his way of refusing to be a slave.”

He adds: “That accident resulted in Daunte’s death, and it reminds me of Nat Turner's rebellion – there were slaves who rebelled even if it cost their lives because they knew what was happening to them was unjust. So that’s why I chose ‘Oh Freedom’.”

Pretty soon, people in the hall start to join in, and as the hall fills with music, either singing along, or else swaying. The church’s choir also adds voice. There are drums and a bass guitar. The song essentially has only three chords, and Drumwight is performing it in E flat major, with a key shift to F. But it is the melody that sticks in the mind, instantly burying itself, a tune that is both simple yet fragile. Drumwright’s voice swells as he works through the verses.

“No more weeping. No more weeping. No more weeping over me.

“And before I'd be a slave, I'd be buried in my grave.

“And go home to my Lord and be free.”

Robert Darden is a professor of journalism, public relations and new media at Baylor University in Texas, and heads its black gospel music restoration project. He says it would not be the first time that a first-time listener to “Oh Freedom” would leave the performance humming the tune. He believes the song’s longevity has resulted in it being stripped down to its most basic essentials: just the melody, and the words that had to be remembered.

Like many spirituals that exist to this day, “Oh Freedom” has no credited author, and for generations was passed on only by being sung, and being sung frequently. Having been passed on so many times, he says, will have resulted in it being stripped to its elements. At the same time, the simplicity has made it a simpler vessel to pass on.

“It first shows up around the time of the American Civil War with various names, as a spiritual,” he says, speaking from Baylor, in the city of Waco. “But it's from a subset of the spirituals that I call the protest spirituals, and as much as the slaves knew what it was about, the owners of enslaved peoples didn't know.”

Darden says the song appeared to have been lost after the Civil War, but then appears again after the end of Reconstruction, that brief flickering period of just a dozen years when it seemed black people might receive the rights promised to them by Lincoln and others, only to see the effort sabotaged, and federal troops withdrawn from the US South. It enabled the South to embark on a century of Jim Crow laws, a form of apartheid that many said was little better than slavery itself.

Darden, is a former gospel music editor for Billboard magazine, and the author of two books on black music, including Nothing but Love in God's Water: Volume 1: Black Sacred Music from the Civil War to the Civil Rights Movement.

He says “Oh Freedom” contains a hidden message, something that historian Dr Henry Louis Gates calls double-voicedness, which was only understood by those singing it. In essence, it was a freedom song. “Some of these songs like ‘Oh Freedom’ are so in your face, you don't know how some white [owners] could not know if this was really about freedom from them and getting over the Ohio River, and not River Jordan and Jesus.”

Another spiritual long believed to have a hidden message is “Swing Low Sweet Chariot”. It became associated with Harriet Tubman and the underground railway, which helped break slaves out of their bonds.

Bishop Richard Howell of Shiloh Temple, who hosted the funeral, says: “‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’ was a code – that tonight a ride is going to be coming to take the slaves away from here. So a lot of the songs had a message to them. The white farmers did not have a clue what they were doing. But they were singing code songs to each other.”

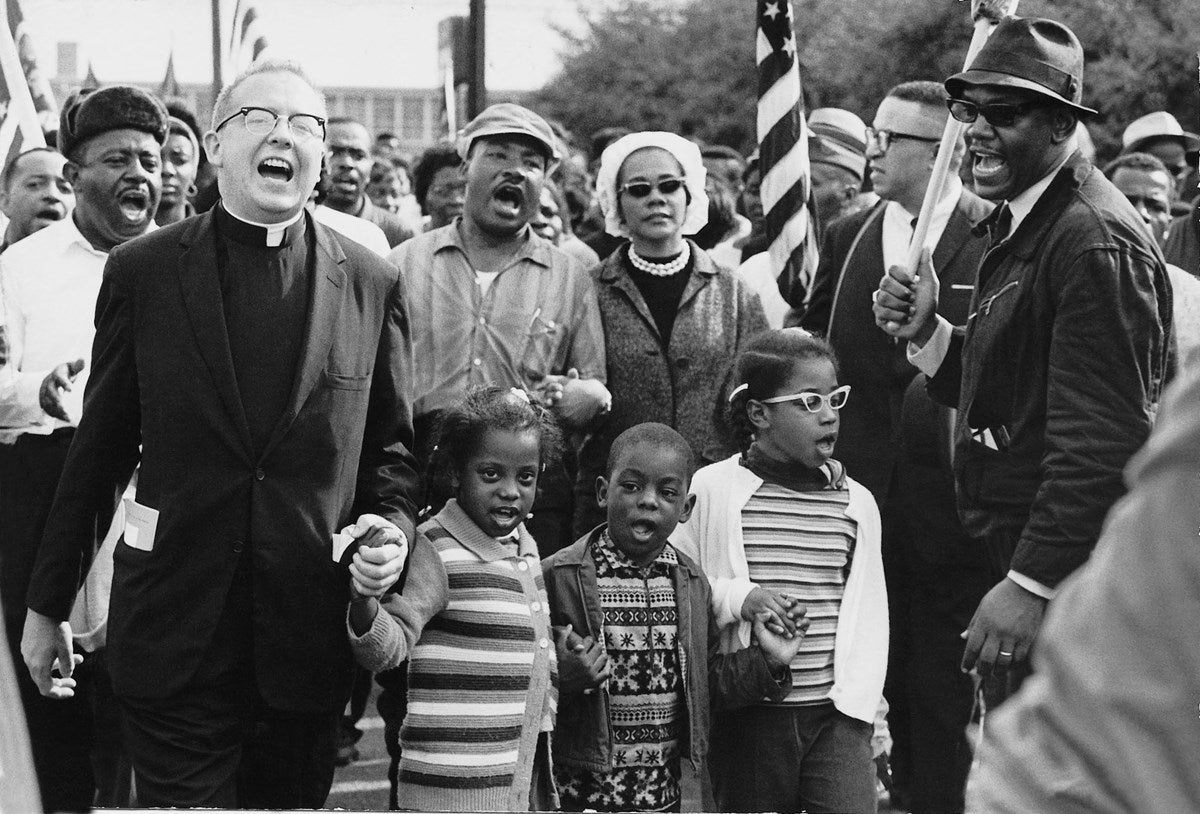

Another reason for the longevity and durability of songs such as “Oh Freedom” and “We Shall Overcome” is that they could be adapted to the times. Both were performed during the 1950s and 1960s as part of the civil rights struggle.

Odetta Holmes, the late blues, jazz and folk singer, sang what is believed to have been the first recording of “Oh Freedom” as currently constituted in 1957, and was included on the album Odetta Sings Ballads and Blues as part of the “Freedom Trilogy”, along with “Come and Go With Me” and “I'm on My Way”. It was released by the briefly lived Tradition Records, which was based in New York. (An earlier version may have been recorded by the ER Nance Family as early as the 1930s.)

In a 2007 interview with the New York Times, Holmes said of the songs she chose to sing: “They were liberation songs. You’re walking down life’s road, society’s foot is on your throat, every which way you turn you can’t get out from under that foot.”

She added: “And you reach a fork in the road and you can either lie down and die or insist upon your life.”

You’re walking down life’s road, society’s foot is on your throat, every which way you turn you can’t get out from under that foot

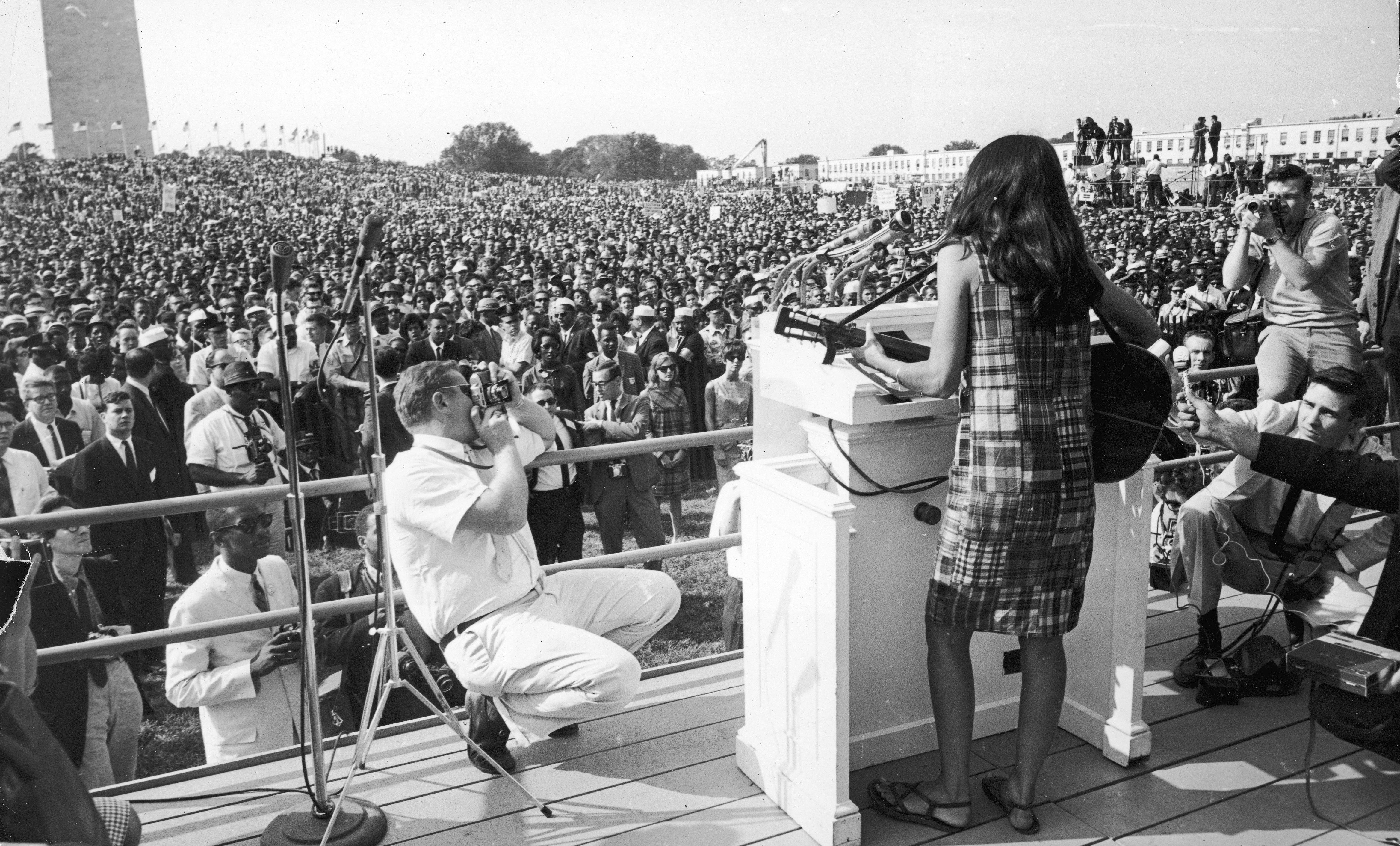

The song is also associated with Baez, who recorded a version in 1958 when she was just 17. It was also released by her label without her permission in 1964 on the album Joan Baez in San Francisco. A year earlier, Baez had opened a series of performances that would include Dr Martin Luther King’s “Dream” speech during the August March on Washington. At the same event Holmes performed “I’ll be on my way”.

There have been many versions of the song, including a powerful rendition by Harry Belafonte. Darden says Seeger described “Oh Freedom” as a “zipper song”, meaning it could be tweaked for a performance depending on the location.

“So if there was a particularly heinous sheriff in Birmingham, and his name was Smith, you could drop that into the song and then continue with you know ‘proud to be a slave, and I’ll be buried in my grave’,” he says. Songs such as “We Shall Overcome” were sung during events such as the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Tiananmen Square massacre and even the Arab Spring. His personal favourite version of “Oh Freedom” is an acapella rendition by The Golden Gospel Singers, founded in Harlem, New York.

Drumwright is not the only musician at the service, nor is he the sole performer. Grammy-award trumpeter Keyon Harrold performs “Amazing Grace” while an artist creates a painting of Daunte. The musician hit the headlines last year after a white woman wrongly accused his son of stealing her phone at a hotel in New York. Crump says the musician had “de-escalated the situation”, unlike the police in Minnesota.

Yet top billing is for Al Sharpton, the 66-year activist, television host and preacher who, in 1972, served as youth director for the presidential campaign of Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, not only the first black woman elected to Congress, but also the first African American to run for president.

Afterwards, he spent seven years working as tour manager for the late James Brown, whose bravura he manages to still channel. In a 2007 interview he said: “What I do functionally is what Dr King, Reverend Jackson and the movement are all about; but I learned manhood from James Brown. I always say that James Brown taught me how to be a man.”

Sharpton does not take long to get the crowd on its feet. He says of the family of the young man whose body lies in a white casket: “You can never fill the hole in their heart caused for no reason.”

I haven’t seen a funeral like this since Prince. Well, we came to bury the prince of Brooklyn Center, because you hurt one of our princes. You thought he was just some kid with an air freshener, he was a prince

He then turns to city’s late celebrated musical hero, Prince, who died in 2016, and adds: “I haven’t seen a funeral like this since Prince. Well, we came to bury the prince of Brooklyn Center, because you hurt one of our princes. You thought he was just some kid with an air freshener, he was a prince. Minneapolis is stopped today to honour the prince of Brooklyn Center.”

Bishop Howell says the music played in black churches binds the community together. “Singing is second nature to us in the church, and we use that to celebrate, we use it to mourn, we use it to sing hope, to sing justice, to sing peace. But most of our songs are glorifying Christ. And when we praise Christ, these songs accompany the expressions of how we're feeling.”

He says the song “Oh Freedom” that Drumwright has sung is to “show how far we have come, but how far we have still to go”.

He adds: “Even though we are here to celebrate the life of a 20-year-old kid whose life was snuffed out of him right like that, you're not going to take our freedom away. We’ve worked too hard to get to where we are. We're not about to turn around now.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments