How Sheffield rose as Nottingham fell

Mary Dejevsky recently returned to Sheffield and Nottingham to see how the cities of her childhood have changed, and what effect Boris Johnson’s ‘levelling up’ agenda may have on them

This is a tale of two cities, separated by less than 40 miles in the middle of Britain, and how they changed places. They are familiar to me from what seems like the distant past, but also from more recent years. One is where I lived until the age of 12. The other is where I spent the next six years of school. I have returned to both many times since and I have followed the fortunes of younger relatives as they took places at their universities. These two cities are Nottingham and Sheffield.

Nottingham was a successful, outward-looking market city, way back when, with a thriving manufacturing industry, a well-regarded university and an equally well-regarded polytechnic. It was a manageable size and it had a thriving city centre, with the Council House, the market square and the Theatre Royal at its heart. It had the Goose Fair every autumn and a successful football team in Nottingham Forest who won the FA cup In 1959. In fact it was such a big civic event that we primary school children made a model of the pitch and learned the names of the team by heart.

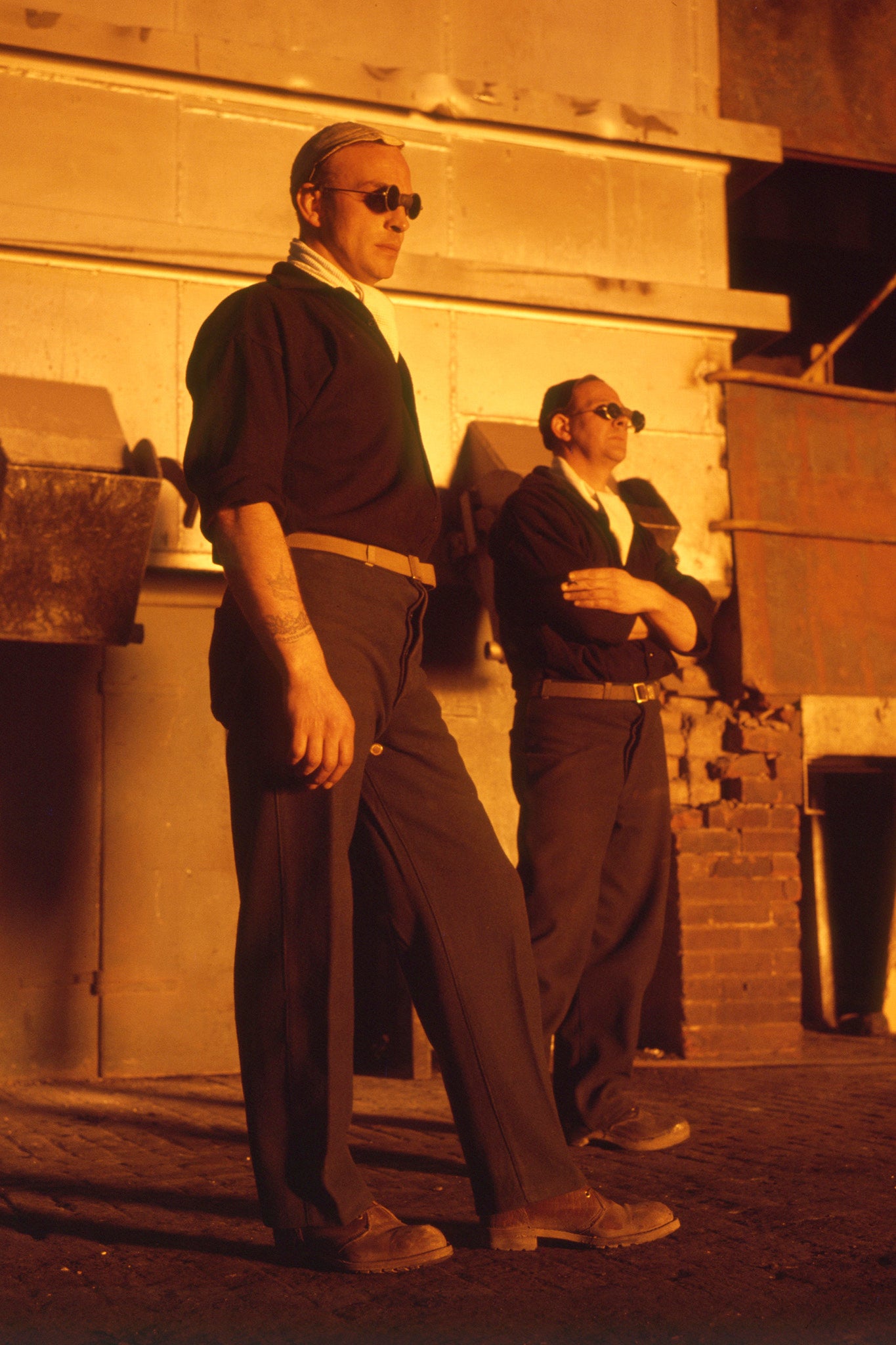

When I arrived in Sheffield, just a few years later, it was a defensive and depressed place. It seemed marooned in the ruins of what passed for the nation’s steel industry and in many ways epitomised William Blake’s “dark satanic mills”. Spread across multiple hills and divided by no fewer than five river valleys, it defied easy navigation. We kept getting lost, and I still do. Starkly divided between the haves on the western fringe and the have-nots everywhere else. It was a Labour fiefdom, second only to Liverpool in the party’s dominance of the city council, and David Blunkett was elected the country’s youngest councillor at the tender age of 22. Those were the 1960s going into the 1970s.

To me, the outlook, the accents and the allegiances of the two cities suggested a much greater distance than 40 miles. Sheffield was, and still is, proudly Yorkshire – South Yorkshire, to be precise. Nottingham was and is the East Midlands. Never the twain were to meet. In those days they observed and compared each other as rivals, and to an extent they still do. The different character of these two cities made it almost inevitable that they ended up on opposite sides in the miners’ strike two decades later.

The genesis of this article goes back two or three years, when I went to speak at Nottingham University, and took the opportunity to stay awhile and revisit old haunts. I returned home – I admit it, to London– little short of horrified. What I had remembered as a neat and smart city of just the right size, with a well-proportioned civic centre bustling well into the night, seemed to have seen better days. It looked dispirited and down-at-heel. By 9pm on a Friday night, central streets were nigh deserted – this was well before the pandemic had struck.

Yes, there was a smart new tram system, that trundles you from north to south and east to west in a half-hour or so, but most of what you see in between hardly lifts the mood. The district where I spent my earliest years – Forest Fields, close to the centre – looked poorly cared for and poorly served in terms of useful shops. Commercial premises were boarded up and litter abounded.

Also, the city just did not seem to hang together. The introduction of the tram – a service that has helped bring other cities together – seemed to underline just how far Nottingham’s suburbs lived their lives apart. Basford, where my infant school was, when it was lined with working factories, seemed a smoke-stained wasteland. Wollaton, where we moved when I was about 10, with its deer park and stately home-turned-museum, felt even more of a village-y world apart than it did then, although it is not too far from the centre.

The University of Nottingham, which had been almost at the bottom of our road, seemed a lot less connected to the city than it had before – a campus island bounded by the tram and major roads, with the green haven the exclusive preserve of students and their teachers in between. Not somewhere you might just nip over the fence to enjoy the grounds.

The Queen’s Medical Centre, a state of the art teaching hospital and a jewel in the city’s crown since its opening in 1977 remained a source of pride, but had lately come in for less enthusiastic reviews. Last year (2020) an appraisal rated its maternity services “inadequate”. That is not what any city wants to hear.

The university – once able to demand the very top A-level grades – has been slipping down the popularity stakes among would-be students, too. I know students who have dropped out, saying they felt unsafe in the areas dominated by student housing and what they saw as a corrosive separation between town and gown.

With Covid hopefully in retreat, the Afghan crisis on hold and the climate change conference, COP26, still weeks away, ‘levelling up’ is due for a return

By the time I boarded the train for home, the rose-tinted lenses through which I had viewed Nottingham for decades were by now so thoroughly shattered that I decided to take a fresh look at Sheffield. And the change in 20 years or so had been astounding – almost entirely in the opposite direction. In some ways, what has happened is reminiscent of the renaissance of parts of Central Europe since the communist collapse.

In contrast to Nottingham, the Sheffield I returned to came across as a lively and conspicuously friendly sort of place, where people seemed comfortable purposely going from A to B or just pottering. I have never been called “darling” or “pet” so benevolently, so often. Sheffield, too, had installed a tram – a super-tram, no less – which seemed to draw the city together more than pull it apart – though it had also drawn criticism by diverting custom from the city centre shops to the mega-mall out at Meadowhall.

The centre may have lost custom – and was anyway never as harmonious as Nottingham’s market square – but it had also been made walkable in a way it used not to be. The Moor, an increasingly scruffy shopping thoroughfare when I was in my teens, had been pedestrianised, with stalls and seating down the middle and a spacious new covered market opened at the further end. When the sun came out, it was almost possible to believe that Tony Blair had been right about cafe culture crossing the Channel.

Hotels and eateries had proliferated, especially the eateries, which had once been so few and far between that, as a family, we usually booked celebratory meals in one of the few starred hotels. A local journalist told me that, as food and drink reporter for the Sheffield Telegraph a few years ago, she could hardly keep up with the openings.

Higher education had expanded exponentially, with the University of Sheffield and the former polytechnic, Sheffield Hallam University, implanted all over the west and central parts of the city. Students were much in evidence; many stay during their holidays and find work without difficulty to eke out their student loans, while many graduates, I was told, choose to stay in the city because they like it so much.

Sheffield always valued its green spaces – though there was a hiccup pre-pandemic with a row that made the national media about tree-felling outside Endcliffe Park. In all, though, when I went to Sheffield pre-pandemic, it seemed to have become a more liveable, more relaxed and less “chippy” city than it was all those years ago.

I am writing this just after revisiting both Sheffield and Nottingham, in part to see how the impressions of three or so years ago hold up now, as the country emerges from the pandemic, but also with other thoughts and questions in mind. In particular, thoughts and questions about Boris Johnson’s government and its “levelling up” agenda.

With Covid hopefully in retreat, the Afghan crisis on hold, and the climate change conference, COP26, still weeks away, “levelling up” is due for a return. And to quibble, as some do, that “we don’t know what ‘levelling up’ means”, is disingenuous. It means narrowing the gap between those places that are doing well and those that are not – and the way that Nottingham and Sheffield seem to have swapped places within living memory is surely pertinent here.

What makes a liveable and successful city? How can failure be transformed into success, and then nurtured and sustained? Why do some cities seem to thrive consistently, while others seem always to languish, and yet others arise phoenix-like out of an ostensibly terminal decline? When I left Sheffield in 1970, I would never have imagined it as it is today.

And one very basic point that the contrasting fates of these two cities seem to make is that “levelling up” is not, despite the common perception, a simple matter of North versus South. Nottingham and Sheffield are geographically close on the national scale, with Nottingham to the south.

Some research about cities has suggested that some may be too small or too close to bigger cities to flourish, as people and business gravitate to where the money and everyone else seems to be: the towns around Manchester being a case in point. And this could play a role here. Nottingham, with a population of 680,000 is smaller than Sheffield at 850,000, but it also has more competition within the immediate vicinity, from Derby, Leicester and Newark, than Sheffielddoes, which has arguably become the regional magnet. In other statistical respects, though – overall GDP, per capita GDP etc – the two are pretty comparable.

Basic history and economics have probably exerted more influence on their respective fortunes today. The Nottingham I knew as a child was a thriving manufacturing and trading city. The lace and textile industry was fading, but Boots, Raleigh Cycles and Players tobacco were big local employers. Just look at those industries, and Nottingham somehow seems to have missed the boat. It was into bikes before they became fashionable. Boots was taken over and has faced retail competition, and tobacco... enough said.

What is more, Nottingham seems to have been unable to capitalise on the huge recent expansion of higher education, as Sheffield has done to such advantage. Nottingham Trent, the former Tech, is highly thought of and has good connections with the city, but Nottingham University – although fashionable for a while – occupies its island on the fringe of the city and, according to some critics, has been more interested in setting up satellite campuses in Asia than talking about joint projects with the city council.

Nottingham has also missed the boat in terms of international and local tourism. Critics say it has rested on its Robin Hood laurels, without having much to show for the Merry Men in the city itself, and Sherwood Forest itself being a good 45 minute drive away. A recent renovation of Nottingham Castle has tried to exploit the connection, but has been lambasted for trying to appeal to an international market that has been not materialised and pricing locals out of even a stroll in the grounds.

The Nottingham-Sherwood Forest difficulty points up another peculiarity of Nottingham, which is that the area of the city is small, and has long had poor to non-existent relations with the county of Nottinghamshire that surrounds it. It is no coincidence that there are two football teams: Nottingham Forest and Notts County. City and county tend not to make common cause, even though it would make presentational, as well as economic, sense.

And, talking of the economy, the Nottingham of today – and I was astonished to discover this – has been judged the poorest city in the whole of the UK in five of the past seven years. Although you can contest the measure, which was by household disposable income, or the calculations, and Nottingham loyalists do. Instead they cite the small size of the city and the fact that the bigger and more prosperous county is excluded as distorting factors, which may be so. But Nottingham also comes high in the league of workless households, and when you arrive and confront, among other things, a gigantic and idle demolition site right opposite the station, you cannot escape the impression of a city that is not doing well.

So how come Sheffield, which I found such a mostly desolate place as a teenager, has come up since then, while Nottingham has gone down? One reason, that can’t be dismissed, might be that Sheffield just had nowhere to go but up.

One reason might be the stake that it placed on higher education and that its universities have a presence across the city. Not only is there less conflict between town and gown than in many places, but I was told that more students involve themselves in local politics and voluntary organisations than happens in many other places, and relations between the city and the educational authorities are good, with each seeing the other as a benefit.

With the traditional steel industry gone, Sheffield not only capitalised on periodic bouts of enthusiasm for dispersal from London by attracting banks and government offices, but also built on old strengths to develop a specialist, precision steel sector.

Sheffield was also able to conjure hope out of despair in another way, too. The city centre, which was never a thing of great beauty, has been dug up and remade so often that there were times when local businesses, fed up of empty streets and high crime, simply left and started up elsewhere. That elsewhere, though, was still Sheffield, not least because Sheffielders, both native and adopted, feel tremendous loyalty to their city. The result is clusters of new markets and neighbourhood commerce catering to the influx of students and professionals, but to locals, too.

The future for Nottingham may not be quite as bleak as I have painted, similarly, the picture for Sheffield may not be quite so rosy

Sharrow Vale, a nondescript street where my brothers went to primary school, is now a cheerful melee of craft shops and cafes and studios and salvage yards so popular that a one-way system and parking meters have been required. Shopkeepers told a similar story of frustration with the city centre and delight at their flourishing new Bohemia, which has arisen in just the last 10 years.

Sheffield has also stolen a march on Nottingham in the culture stakes. A forthcoming book, Stirring Up Sheffield – written by the late director of the Crucible Theatre, Colin George, and his son, Tedd – charts the battles that attended eventual approval of the theatre’s then unconventional design, and the way it has since given Sheffield something of a national presence, not least following the contested decision to stage the Snooker championships there. What also emerges from the account is the civic and cultural rivalry that existed at the time – the late 1960s – between Nottingham, which had a flourishing avant-garde Playhouse, and Sheffield, which was trying to catch up. How different Sheffield’s cultural profile might now be without the Crucible.

Sheffield has other assets, too, that have grown in significance in recent years. It has plentiful housing at a relatively reasonable price, and some spectacular landscape in its environs – the Derbyshire Peak District and the Yorkshire Dales – that competes with more famous beauty spots elsewhere. Improved public transport and the current growth of walking and cycling have put Sheffield on a new national map as a centre for exploring the great outdoors.

A comparison of the two cities would not be complete without mentioning the dreaded subject of politics, which may also be relevant in any debate about “levelling up”. The city of Nottingham was once quite evenly divided between Labour and Conservative. Over the past 30 or so years, though, it has been almost as dominated by Labour as Sheffield used to be. Of 55 councillors, 50 are currently Labour, and, as in the Sheffield of old, some blame one-party rule for poor decisions, unchanging patronage and stagnation.

Sheffield over the same time has gone the other way, with Labour’s hold far diminished and the virtual wall between True Blue Hallam and the Red Labour crumbling. Since 2000, control has shifted between Labour and the Lib Dems, with periods – as now – with no one party in overall control. A sign of changing times was Nick Clegg’s election in 2005 as MP for Hallam, and although he left politics following his party’s collapse after serving in the coalition, the Lib Dems and the Greens have made inroads into Sheffield politics in a way that has softened the city’s historical divide and arguably improved both representation and decision making.

The point here is not about the merits of one or other party, but about the liabilities that may attend entrenched one-party power in local politics. You could even argue that Sheffielders have done their own “levelling up” all by themselves.

Finally, it is worth noting atmospherics, and where better to sense this not just on the streets, but in the local media. Just take a look at two of the venerable newspapers that serve these cities: the Nottingham Post and the Sheffield Telegraph. The Sheffield paper seems full of upbeat news and activities: a new grant for a laudable volunteer effort here, new businesses there, a feature about the pluses and minuses of the glorious, but dangerous, Snake Pass, amid concern that a promised replacement route may not happen; a run-down of “exciting Sheffield events”. There is less positive news, to be sure, but the tone is forward-looking and optimistic.

Turn to the Nottingham Post, and oh dear. The place comes across as a hotbed of crimes of all descriptions, starting on the front page with a “schoolgirl subjected to 'terrifying' sex attack on Maid Marian Way” – that’s right in the city centre, by the way. From drugs to fights to someone jailed for putting out a racist video about Priti Patel, to a “homeowner” relating his “disaster saga” over his new-build home, to a two-day suspension of the city’s tram service, to “fear” as nearby Mansfield “becomes one of worst-hit areas for coronavirus cases” in the country, Nottingham has it all.

Of course, there’s an element of chicken and egg: how far do the media contribute to making the climate and how far do they reflect it? In other respects, though, it doesn’t matter. The local media gives an idea of how people feel about the place, and the vibe in Nottingham and Sheffield could not be more different.

At the same time, however, the future for Nottingham may not be quite as bleak as I have painted, similarly, the picture for Sheffield may not be quite so rosy. In the three years between my last visit to Nottingham and now, even with the pandemic in between, Nottingham seems to have perked up a bit. Some of the factors that may have put a distance between the university and the city, including its focus on overseas branches, may now be going into reverse. Post-pandemic, pharmaceuticals promise to be a big area of development. Can Nottingham turn that to its advantage?

In Sheffield meanwhile, the very centre is still a work in progress. It appears much of the reconstruction stalled during the pandemic. Plus, the decision by John Lewis to close its one flagship store was taken very badly, not just by the council but by Sheffield’s shoppers, some of whom are boycotting Waitrose in protest.

I rather think the city will survive the insult, but it serves as a reminder, perhaps, of the uncertainty inherent in the best of planning, with the reversed fortunes of Nottingham and Sheffield offering a graphic example for our times. As for “levelling up”, a whole set of complex factors contributed to Nottingham’s decline, while Sheffielders might reasonably argue that they levelled their city up all by themselves.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments