Has the debate about drug decriminalisation moved on at all in recent years?

The Netherlands has had a long-standing policy towards the use of cannabis, but the picture is far more complex than it seems, suggests Cherry Casey

At the Holland Pop Festival in Rotterdam, June 1970, 150,000 civilians gathered for three days of performances from Pink Floyd, Jefferson Airplane, The Byrds and Mungo Jerry. Dubbed the “Dutch Woodstock” it is also widely considered the point from which authorities in the Netherlands began establishing a tolerance toward cannabis. The drug, which was being openly smoked by festival goers, was observed by plain-clothed police officers as one that did not seem to cause any particularly concerning or disruptive behaviour.

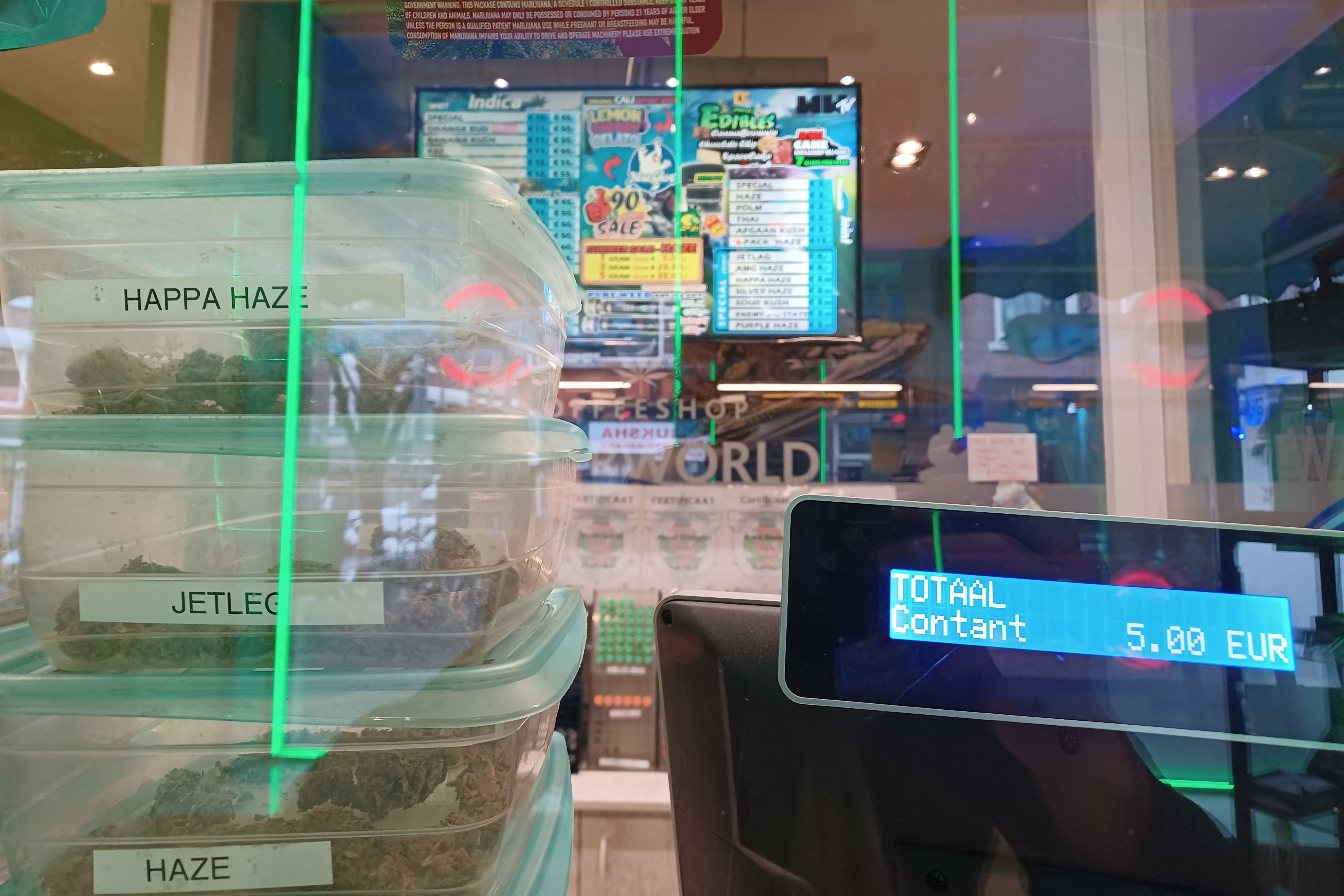

It was decided therefore that while the government would not go as far as legalising cannabis, a small amount for recreational use would be tolerated, and could be purchased from specified retailers – the now-famous coffeeshops. In large part, this was to control the use of cannabis rather than push it underground where it would risk becoming a gateway to more harmful drugs.

Arguably, they have had some success on this front: in the 2019 European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) report, there were 262 overdose deaths in the Netherlands in 2017, equating to 22 deaths per million – the European average. In England and Wales, in the same year, there were 3,756 drug-related deaths, equivalent to 66.1 per million. By 2020, this had risen to 4,561 and 79.5 per million, respectively. Staggering figures but perhaps unsurprising given that, in its 2015 report, the EMCDDA found that Britons used more drugs than any other European country.

While the Netherlands assessed the harm that cannabis caused and created a regulation policy accordingly, President Richard Nixon was waging war on drugs and – despite the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse actually recommending its decriminalisation – was determined to crack down on cannabis. The UK created its own Misuse of Drugs Act in 1971, and while the original plan was to have “hard” and “soft” drugs – with cannabis categorised as the latter: “People wouldn’t accept cannabis was a ‘soft’ drug” says neuropsychopharmacologist Professor David Nutt, who has repeatedly called for the decriminalisation of cannabis. Instead, it was considered Class B where – apart from a brief foray into Class C in the noughties – it has remained ever since.

As part of the Home Affairs Select Committee’s ongoing inquiry into drugs, a specific meeting focused on whether the Misuse of Drugs Act had been successful. When posed with this question, Martin Powell, head of partnerships at Transform Drug Policy Foundation responded: “With the danger of sounding sarcastic, in England alone, heroin use has risen from under 10,000 people in 1971 to 260,000 today, an over 25-fold increase. We also have 19,000 people using heroin in Wales [and] another 57,000 in Scotland.” We also have 2.5 million cannabis users in England and Wales, he added – a more than five-fold increase since 1971.

Indisputably, the current system isn’t working. One reason why, says Nutt, is that prohibition leads to perverse consequences if people look for more potent substances. Examples abound, but two of the most timely are spice, the synthetic cannabinoid that has proven far more harmful and unpredictable than cannabis, and fentanyl, a synthetic alternative to heroin that Nutt describes as “the biggest threat” to Britain today. “Heroin supplies became very difficult due to a UN block [on morphine],” he says. It was realised that not only could fentanyl be made in a lab, but was “50 times more potent and half the price to make. And it’s created this monster.” Last year, fentanyl caused more than 70,000 deaths in the US.

Niamh Eastwood, executive director of the charity Release, and an inquiry witness argued that the criminalisation of drugs is in itself a gateway to the criminal justice system, a sentiment that James, who was sent to prison in the 90s for the possession of ecstasy, wholeheartedly agrees with. If you “slap someone in prison, traumatise them, destroy their lives, give them a criminal record, [they’re] more likely to be back in crime, or using drugs,” as a result.

Eighty per cent of drug offences in the UK are for personal possession. For example, in 2021,125,000 offences were specifically for personal possession of cannabis. This was the case for James, who bought a bag of ecstasy pills while a student in Manchester during a time and place when the nightclub scene had erupted. The police raided his house the following day, it looked suspect and the police were looking for crack, says James, but his drugs were found.

We cannot have a sensible public health response to drugs while simultaneously arresting and punishing users

James was sentenced to two-and-a-half years and sent to a variety of “really rough” prisons, including Strangeways in Manchester. Drugs were rife and he could “easily have become a heroin addict.” He served 15 months in total, but 30 years on the impact of having a criminal record remains. “I’ve managed to eke out a living but I earn a fraction of what my peers do,” he says. Academia is one route James has considered, but as it’s feasible he’d need an “enhanced check” to do so, which would show his record. “A lot of doors are shut to me. And it’s the same for millions of others in the country.”

The cost of illegal drugs to British society is around £20bn per year. Portugal was widely referenced during the inquiry – with the country having decriminalised many drugs in 2001 – and is often seen as “the poster child”, says Steve Rolles, a senior policy analyst at Transform Drug Policy Foundation, despite the fact around 45 countries around the world have decriminalised either the possession of cannabis or of all drugs. Partly this is because their policy was introduced so long ago, he explains, but also because their results are more impressive than others. While the country at one point accounted for 50 per cent of yearly HIV diagnoses linked to injecting drug use in the EU, for instance, that figure has reduced to just 1.7 per cent. Drug death rates in Portugal remain some of the lowest in the EU at six deaths per million, compared to the EU average of 23.7 per million (2019).

Dame Carol Black, who has spent two years conducting an independent review of drugs, was a key witness to the inquiry. However, for her review, she was not permitted to look at legalisation or decriminalisation. “Nothing was off-limits, except arguably one of the big structural drivers of problems in the UK,” says Rolles. During the inquiry, when questioned on Portugal’s success, she commented: “Portugal, when it decriminalised drugs, put in a massive investment of money and services. Nobody really knows whether the great improvement ... is due to the really important investment, the improvement and availability of services, or what percentage was due to a change in the law.”

Rolles agrees that Portugal’s approach was successful specifically because decriminalisation was one part of “a broader reorientation of policy, moving away from the criminal justice system and towards a public health model. They also invested in drug services, treatment and harm reduction. They stopped sending people to prison and instead send them to relevant services.” Decriminalisation on its own will not transform a country’s drug problem, says Rolles, but it is a necessary enabler. We cannot have a sensible public health response to drugs while simultaneously arresting and punishing users.

The Netherlands were arguably one of the first to hold this opinion, but it has not been without complications, with the Mayor of Amsterdam, Femke Halsema, recently announcing that she will once again be pushing for the ban of the sale of cannabis to tourists in the capital. “Many of the major problems in the city are fuelled by the cannabis market: from nuisance caused by drug tourism to serious crime and violence,” she told Dutch News.

A four-year pilot scheme is on the horizon, during which time the government will monitor how it may be possible to regulate the supply of cannabis to coffee shops. Whether tourists will be banned as part of this pilot, remains to be seen.

Legal regulation is a move Rolles’ organisation supports, but with an important caveat: “my take is the more commercial models are potentially problematic,” he says. “You don’t really want profit incentives for people to increase consumption or initiate new users or target the young and vulnerable population with branded products and lifestyle marketing. We support legalisation but not a laissez-faire commercialised market where profit is put above concerns with public health.”

Look away from the US, Canada and indeed the Netherlands, and towards Malta, says Rolles, where the production of cannabis will be regulated but within a non-commercial environment, or Uruguay, where cannabis can be traded within non-profit co-operatives and registered individuals can purchase unbranded cannabis from pharmacies.

While Black’s remit did not include making recommendations around structural changes in the law, during the inquiry she commented that “in countries where drugs are legalised … you do not get rid of the black market. In fact, you have a black market that often is selling a worse form of the drug.” Both Rolles and Nutt agree that you can never realistically eliminate the illegal market – the aim is to reduce it drastically. She did, however, endorse diversion schemes that should, “ensure that far fewer people go down the criminal route.”

It is complex and there is no perfect solution, but we have to decide what our priorities are, and one of which must be better education

“They don’t like calling it decriminalisation,” says Rolles, but diversion schemes exist in numerous police authorities across England and Wales, where if you’re caught in possession of a small amount of drugs for personal use, they’re confiscated but you’re not prosecuted. Instead, “you’re diverted into some form of health intervention or treatment assessment.” This has also been the case for the whole of Scotland since late 202. Anything more formalised cannot happen without the Misuse of Drugs Act being amended. And with the foreword to the government’s 10-year drugs strategy, published 2021, suggesting that decriminalisation “is often suggested as a simple solution to many of the problems caused by illegal drugs. This is not the case,” it seems that any possible change may be a long way off.

“There’s a fairly long-running historical problem of the health challenges of drugs getting drawn into the law and order politics,” says Rolles, rather than a public health or social policy. “It’s a fundamental category error,” he says. And after generations of the same “battle against the scourge of drugs” narrative, he says: “It’s difficult to back away from, as it’s automatically seen as supporting the bad side.” Particularly frustrating given that, says Rolles, “when you speak to politicians off the record, they all get [decriminalisation], but just don’t want to say it.” Nutt agrees that there is enormous political leverage from being tough on drugs. Drugs have been a very convenient political weapon to beat the opposition with.”

But language has consequences and Powell argues that this “tough on” narrative “undermines support for treatment and compassion among the public because you are stigmatising people … [while those] who have problems with drugs do not want to engage because they think they are going to be punished.” Eastwood cited a higher education report suggesting that 30 per cent of students were not willing to come forward about drug use for fear of punishment, while 16 per cent were in a scary situation but did not seek help from emergency services due to fear of prosecution. Removing that approach from the strategy, Powell says, is “the single thing that you could do that would most improve engagement.”

Black agreed that while she “could not find, nationally or internationally, good evidence of what would make a difference to reduce general drug taking… The only thing we really know from the international literature is that if you have a campaign telling people to stop, it doesn’t work at all.”

And general, or recreational, drug taking is a growing concern, for good reason; when asked to contemplate the idea that the vast majority of people who take recreational drugs have had no adverse health effects, Black highlighted that, according to her review, there is “increasing harm that is being seen in this country, even now, from powder cocaine, from cannabis, particularly of the THC variety and, from nitrous oxide.” The campaign group, Anyone’s Child, also lists a number of stories of people dying from recreational drug use, such as one 15-year-old who died after taking half a gram of MDMA powder that was 91 per cent pure.

So what could work? “Young people can be curious, rebellious and push back against authority, it’s all part of establishing the parameters of adulthood,” says Rolles. It is complex and there is no perfect solution, but we have to decide what our priorities are, and one of which must be better education. “What you want is for people to make informed decisions about the risks they’re putting themselves in,” he says, using the analogy of unprotected sex; we can’t ban it so we must educate on the risks and make support – and contraception – as accessible as possible.

Research into addiction is another priority, says Nutt. Black also described how little investment there is in addiction: “If it were breast cancer, nobody would have allowed us to get to the state that I describe in my review.” Twenty years ago, she says, Britain had the beginnings of a good system – the National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse.

“We saw drug dependency go down, we saw more people going into and staying in treatment, we saw crime go down, we saw homicide go down, and fewer people went to prison.” The system had what Black refers to as the “clinical part of drug treatment” in place, but was shut down before “the recovery elements”, could be progressed. Something that today, she says, is still desperately lacking.

One move that many experts, is that drug consumption rooms – described by the EMCDDA as aiming to “reduce the acute risks of disease transmission through unhygienic injecting, prevent drug-related overdose deaths and connect high-risk drug users with addiction treatment and other health and social services” – must be introduced in Britain. The Faculty of Public Health last year co-ordinated an “urgent call” for them to be piloted; Black says she would be in favour of such a decision and the Scottish government are currently trying to overcome legal barriers (presented by the Misuse of Drugs Act) to introduce them, as they have the highest number of drug-related deaths in Europe. Boris Johnson opposes such a move, however, as he has said he is not in favour “of encouraging people to take more drugs.”

We are fed “bumper sticker populism,” says Rolles, when the reality is far more nuanced; and that does a disservice, not just to drug users but to the population as a whole. “If you look at the history of drug reform around the world, people do understand it, if you actually take the time to explain.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments