From Narnia to Brexit: CS Lewis and his vision of a perfect England

This green and pleasant land isn’t just the preserve of Boris and his band of Brexiteers. Atheist, liberal pro-Europeans can have just as deep a love of England, writes Mark Jones

Narnia is fast becoming political shorthand for “away with the fairies” and “in your dreams”. Shadow cabinet office minister Rachel Reeves savaged the government’s progress on EU trade talks last month, saying: “They can call it no deal, they can call it an Australia deal, they can call it a Narnia deal as far as I’m concerned.”

And the SNP’s environment spokeswoman said the “sea of opportunities” promised for the fishing industry post-Brexit were "stories of Narnia".

But for the architects of Brexit, the fictional land conjured by the Anglo-Irish author CS Lewis is a very real inspiration. And here’s why.

“A children’s story,” wrote Lewis, “is the best art form for something you have to say.”

He was explaining his reasons for writing the Chronicles of Narnia, a series of children’s stories which first appeared 70 years ago when The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (LWW) was published. If by “best” he meant reaching the highest number of people, he was right: the seven novels have sold over 100 million copies worldwide.

But that’s not what he meant. After 20 prolific years writing poetry, literary criticism, science fiction, parables and popular theology, he discovered that a children’s book was the best way of conveying his devoutly Christian message to the world.

A later writer of fantasy tales for children, Philip Pullman intensely dislikes what Lewis had to say, though he respects the skilful way he said it. To him, the Narnia tales proselytise far too much: they get at his young readers. Lewis would have winced at the charge, but he could hardly deny the evidence. After all, this is the man who wrote “any amount of theology can be smuggled into people’s minds under cover of romance without their knowing it”.

But it’s not only theology that Lewis smuggles into Narnia – past what he called the “watchful dragons” of modern orthodoxy. There are political messages, too. Lots of them.

The opening scene of the LWW, where Lucy, a child from this world, stumbles into a snowy Narnian wood through a wardrobe door, is justifiably one of the most celebrated in fantasy and children’s literature.

But my eye was drawn to the other end of the book. (We don’t have to worry about plot spoilers: everyone has either read the book, read it to someone or had it read to them).

The four children from England are now kings and queens of Narnia. This is how they rule: “They made good laws and kept the peace … and generally stopped busybodies and interferers and encouraged ordinary people who wanted to live and let live.”

I don’t know if Boris Johnson read Narnia as a child. He'd be a rare English middle-class child if he hadn’t. But the adult Johnson could easily lift those words for his next manifesto. As a summary of benign, libertarian Conservative politics, it is nigh-on perfect. And it’s the libertarians who are most on his back now. A visit to Narnia might do him the power of good.

As you read through the chronicles, you realise that, through Narnia, Lewis paints an idealised picture of England to warm the heart of every Brexiteer

In Narnia Lewis created a vision of these islands that Johnson, not to say Michael Gove and Nigel Farage would heartily endorse. It’s a happy, small, independent nation, bursting with neighbourliness and godliness, where the food is honest and healthy, the beer is excellent, where everyone knows their place – and they’re happy with it.

As you read through the chronicles, you realise that, through Narnia, Lewis paints an idealised picture of England to warm the heart of every Brexiteer and every voter who yearns for a proud, independent country before the meddlers, modernisers and bureaucrats got hold of it.

I imagine legions of Narnia devotees recoiling at these words. And it’s a serious charge to level at any children’s author. It happens: in the mid-Noughties, the Spectator magazine alleged Harry Potter was firmly in the pay of New Labour.

Yet it’s true that CS ‘Jack’ Lewis disdained politics and politicians his whole life. He tried hard to stay out of the fray. In 1951, Winston Churchill offered him a CBE. He politely refused, telling Churchill’s patronage secretary that there are “knaves who say, and fools who believe, that my religious writings are all covert anti-Leftist propaganda, and my appearance in the Honours List would of course strengthen their hands”.

Alas, he didn’t, or couldn’t, stay out. There was nothing covert about the headline on an article he wrote for The Observer in 1958: Willing slaves of the welfare state. In it, he argues that do-gooders, reformers and "omni-science" might think they can improve the lot of ordinary people: but it’s all just “interfering” in another guise: “We are less their subjects than their wards, pupils, or domestic animals,” he wrote. “There is nothing left of which we can say to them, ‘Mind your own business’. Our whole lives are their business.”

And here he is in 1963, writing to a sympathetic American correspondent (of which he had legions) about the near-certainty of a Labour government, “with all the regimentation, austerity and meddling which they so enjoy”, he sighs. He thought he would not live to see the Conservative Party return to power. He was right: he died a week later on the same day of Kennedy’s assassination.

Lewis’s conservatism was deep-seated, romantic, individualistic and inseparable from his faith. The early chapters of Surprised by Joy are concerned with the fashionable atheism he espoused from his schooldays. But his atheism was as paper-thin as his professed astonishment that he “did not become a Leftist” during this period.

I’m not astonished at all. Even as a teenager, he was already deeply in love with the music of Wagner, the myths of the North and the Victorian writer of fantasy and religious mysticism, George McDonald. ("A young man who wishes to remain a sound atheist cannot be too careful of his reading," he wrote. On the basis that Lewis was downright reckless).

He was deeply suspicious of modernism and progress. His first book of poetry was published when he was 19: its language and romantic affectations were already dated. At Oxford, he and his close friend, drinking companion, fellow don and literary soulmate, JRR Tolkien, successfully fought the modernists at every turn, keeping anything later than the Victorian period off the Oxford English syllabus.

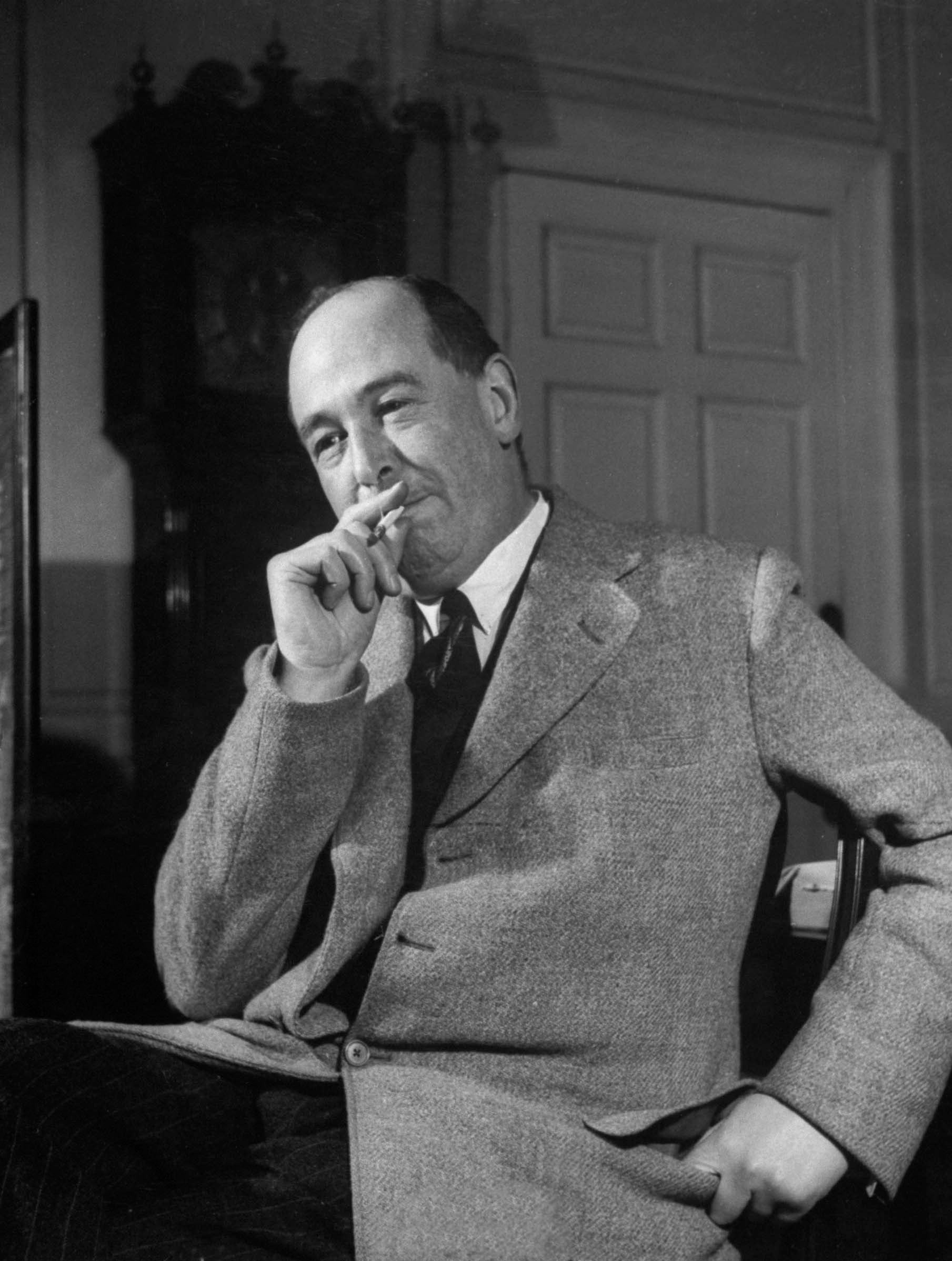

Theirs might have been the Oxford of Brideshead Revisited but Lewis and Tolkien preferred evenings of “beer and Beowulf” and chanting Icelandic sagas. While Lewis’s undergraduate pupil John Betjeman carried a teddy bear and wore bedroom slippers to tutorials, Lewis preferred old tweed jackets, stout shoes and his pipe.

While Lewis’s undergraduate pupil John Betjeman carried a teddy bear and wore bedroom slippers to tutorials, Lewis preferred old tweed jackets, stout shoes and his pipe

So throughout the Narnia chronicles Old is always good and New invariably evil. In the sequel to LWW, Prince Caspian, Old Narnia is suppressed by the tyrant Miraz, a mash-up of Hamlet’s father, Oliver Cromwell and Clement Atlee. A very Lewisian army of talking beasts and semi-divine figures from classical mythology (tree spirits, water spirits and the like), led by Aslan, liberates Narnia from the police state imposed upon them.

Lewis also finds time for a kick at modern education and a history lesson that was “duller than the truest history you ever read and less true than the most exciting adventure story”. You wonder if the future education secretary and reformer of the history syllabus, Michael Gove, was taking note.

If you read nothing else of the chronicles, the first page of the third chronicle, the Voyage of the Dawn Treader will tell you everything you need to know about Lewis’s politics and the kind of teaching he devoutly wished his young readers to avoid.

The central theme of the story is a familiar one: a priggish, unpleasant boy called Eustace Scrubb comes to acknowledge god through the figure of Aslan, learning courage, steadfastness and loyalty along the way. He has a Lewisian mountain to climb.

On that first page we discover Eustace’s mother and father are “modern parents” in the manner satirised a few decades later in Viz magazine. He calls them Harold and Alberta, not mother and father. They are “very up to date and advanced people”. Among their many sins – and there is no question Lewis does view these things as sins – they are vegetarian, teetotal non-smokers who (shame!) like to have their windows open and, bizarrely – what was on Lewis’s mind? – “wore a special kind of underclothes”.

This is identity politics, 1952-style. And by the way, non-smokers are always villains in Narnia. Lewis was rarely without pipe or cigarettes: and of all the meddling the state did after his death, I’m pretty sure he’d have found the indoor smoking ban the most outrageous of all.

In the next book, The Silver Chair, we visit Eustace’s co-educational school, “what used to be called a ‘mixed’ school”, writes Lewis. Some said it was not nearly as mixed as the minds of the people who ran it. That includes the Head, who is eventually sacked, made a school inspector and finally gets into parliament, “where she lived happily ever after”. Note that mordant spin on the usual fairytale ending.

Lewis in particular would have every sympathy with Extinction Rebellion and the fight against HS2

Women and CS Lewis is a subject that requires more than a passing mention – indeed, there’s a whole book called just that. But in making the Head a female, Lewis was returning to a “dread” he voiced in Surprised By Joy – “the dominance of the female and the dominance of the collective”.

The collective also gets a good hammering in the chronicles in the shape of dwarves. There are good dwarves in Narnia. But when they get together to fight for their rights, as Duffers in Dawn Treader and heaven-deniers in The Last Battle, Lewis gives us a patrician satire on trade unionism and working-class solidarity. And despite well-meaning attempts from the likes of Rowan Williams to defend him, Lewis’s depiction of Islam in the shape of Narnia’s sworn enemies, the Calormenes, is just as crude and, well, hard to defend.

At this point, I can hear up to date and advanced readers vowing to keep their nearest and dearest well away from Narnia. Well, don’t. The stories are as magical, thrilling and wonderful as the day they were written. Narnia is still a place we yearn to get to. And if what I’ve written so far tempts you to think of Lewis as a right-wing bigot of the old school – let me now lead you away from that temptation.

Lewis was an “old western man”, as he described himself, a foe of chronological snobbery where fashionable people patronised the ideas and people of the past. But that philosophy also leads him towards something that looks very like modern environmentalism.

I can’t exactly see Lewis and Tolkien lying in front of bulldozers. But Lewis in particular would have every sympathy with Extinction Rebellion and the fight against HS2. When I heard that a 250-year-old pear tree (once the UK’s ‘Tree of the Year’) was to be cut down to make way for the HS2 rail link, I thought of Lewis.

In Narnia, the bad people fell trees and hack roads through forests. When the traitor Edmund is dreaming of power in LWW he thinks of building roads, owning cars and “where the principal railways will run” (as well, inevitably, of “what laws he would make”). Another enemy of Old Narnia, Shift the Ape in The Last Battle promises “roads and big cities and schools and offices and whips and muzzles and saddles and cages and kennels and prisons”.

Note that conflation of bad things. In Narnia, builders, developers and vivisectionists are cut from the same cloth – Lewis wrote passionately in favour of animal rights. Perhaps a government with its bias in favour of planning and many friends in the construction industry can’t be too careful in choosing which works of Lewis to read.

One road unquestionably leads from Narnia to Brexit. Lewis would have hated the notion of a superstate with all the extra “meddling” that implies. He didn’t like French food or French customs, but he understood their attachment to them. Live and let live.

But there are other roads we can take. Lewis had every chance to “get at” me, in Pullman’s words: I’ve read the chronicles dozens of times as well as his adult novels and Christian apologetics. Yet I turned out to be an atheist, liberal pro-European – a Narnia-loving one.

But there is a place where we meet, Lewis and I. It’s an English pub. Like Lewis, I love long walks and, at the end of it, a proper village with a proper pub and good beer. I share his yearning for this land before the motor car took over, before polyester and lycra, radio masts and executive estates, fast food and fizzy beer.

So much so that I’m writing a book retracing Lewis’s walks, finding the pubs where he took refuge and trying to understand the England and Ireland that’s evolved since his death – and since the referendum. Why? Because I don’t see why the Brexit lot should have that land to themselves. Atheist, liberal pro-Europeans can have just as deep a love of Narnia/England and want to defend it from people who wish to do it harm just as fiercely.

The CS Lewis Festival runs 20-22 November. For a full guide of what’s on see here

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments