Osaka’s fallout with the media echoes toxic brawl at McEnroe press event

Tennis press conferences were causing problems long before Naomi Osaka. Simon O’Hagan looks back 40 years to the day that the questions got too much for John McEnroe – and reporters started trading blows

When the Japanese tennis star Naomi Osaka pulled out of the French Open last month in the wake of her decision not to attend mandatory post-match press conferences, she triggered echoes of another high-profile tennis press conference refusenik, and of an extraordinary incident that took place at Wimbledon 40 years ago this summer.

Not everyone will be aware of those echoes, because the incident, which ended up with reporters coming to blows, was an embarrassment for the media, little reported at the time, and had repercussions that were not for public consumption. The events that unfolded have rarely been referred to since.

Only those members of the press who were present when the incident occurred – myself included – are privy to its significance, and will share a sense that what happened in a cramped basement room at the All England Club one sweltering afternoon in July 1981 marked a key moment in the evolution of player-media relations.

While Osaka, whose ongoing break from the sport means she will not be in SW19 this fortnight, clearly had specific issues with dealing with the press, her actions led to widespread questioning of the role of the tennis press conference, and prompted a general feeling that players should not be obliged to account for themselves in public if they did not feel like it. On that fateful day in 1981, the accounting that was demanded was of a different order.

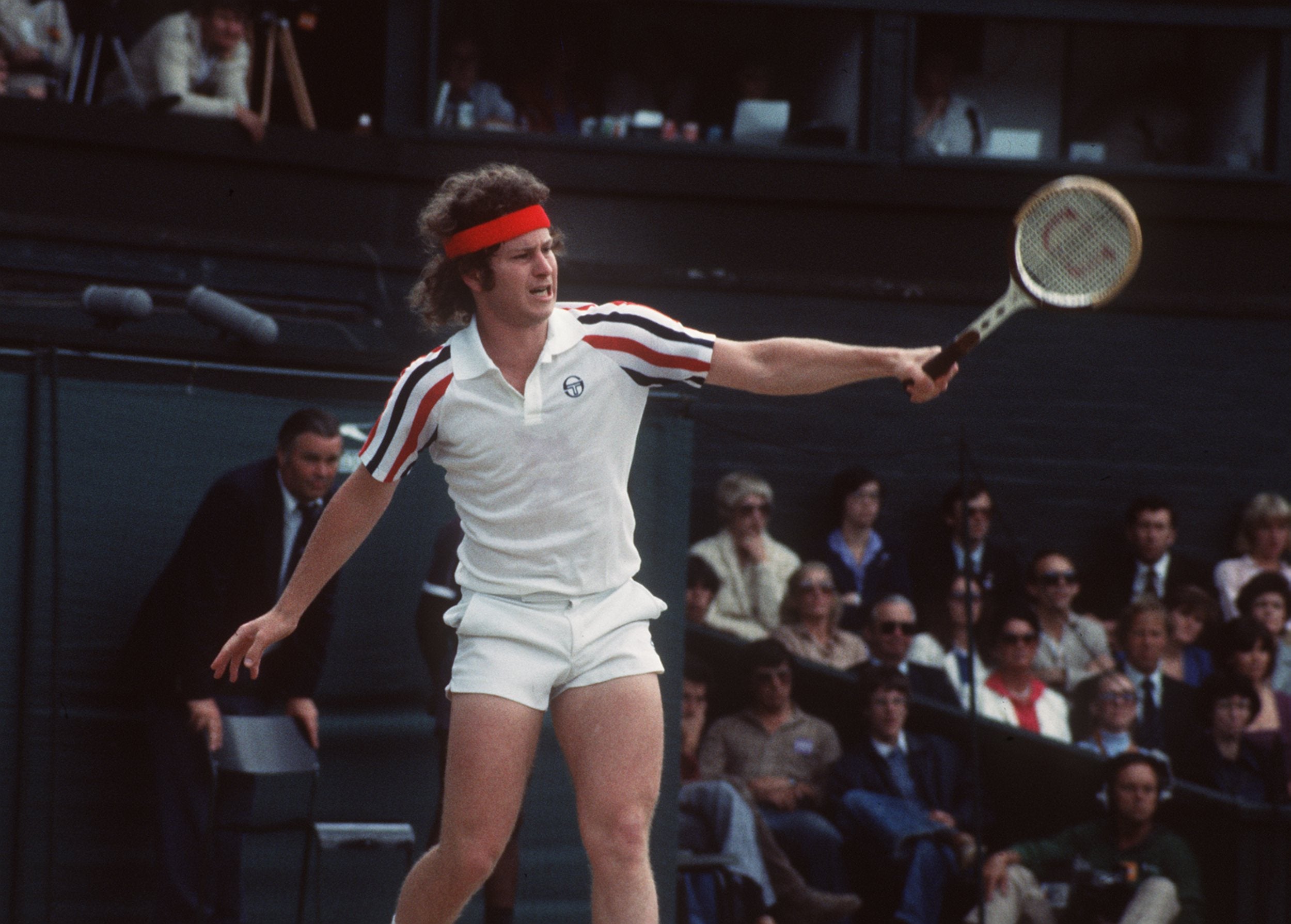

The story is worth re-telling because the press conference in question turned out to be so seismic, and it starts with the identity of the player at the centre of it. We are talking – no great surprise here, possibly – about John McEnroe. A press conference this charged, this bizarre, and this shameful could surely never have come about with the involvement of any other player.

The occasion was a semi-final between McEnroe and a little known, unseeded Australian called Rod Frawley. McEnroe, then 22, was at the height of his brattish powers. The previous year, he had reached his first Wimbledon final, losing an epic five-setter to Bjorn Borg – the match that featured tennis’s greatest ever tie-break. In 1981, these two supreme rivals were on course to meet in the final again – and this time it was McEnroe who would prevail.

The way that McEnroe's genius with a racket combined with his volcanic temper created one of the most compelling personalities tennis had ever known. The game simply hadn’t seen anyone like him before. Love him or loathe him, the public couldn't get enough of this young upstart from New York.

Fascination with McEnroe didn’t stop once he stepped off the court. Soon his private life was on the press's agenda. It wasn’t that stars from earlier eras hadn’t provoked that kind of interest – in the 1970s, both Ilie Nastase and Jimmy Connors were staples of the gossip columns – but McEnroe, perhaps because he was so disrespectful of authority, seemed to forfeit the rights that might have been accorded others.

When Lady Di departed with the match still in progress, there was only one interpretation. Our poor, virginal queen-to-be, driven from her seat, her innocent ears assailed!

His girlfriend at the time was herself a leading player. Her name was Stacy Margolin. She was from California, the same age as McEnroe, and she’d been touted as the next Chris Evert. But her 1981 Wimbledon was not a good one. She was knocked out in the first round. McEnroe, meanwhile, was cutting another swathe through his opponents, not to mention through officialdom. But how were things with Stacy? There were reports that she’d left London on the morning of McEnroe’s semi-final.

Reporters gathering for the match were relishing the prospect. And what added to the potential for even greater copy was the presence in the royal box for the first time of the then Lady Diana Spencer, only a few weeks away from her marriage to the Prince of Wales. Her pre-eminence as an object of obsession on the burgeoning tabloid scene was undisputed. But McEnroe was a terrific sideshow, and to have the two of them in the same story was a reporter's dream.

McEnroe did not disappoint. He snarled his way to victory in trademark fashion, throwing tantrums and abusing line judges, and when Lady Di departed with the match still in progress, there was only one interpretation. Our poor, virginal queen-to-be, driven from her seat, her innocent ears assailed! Send McEnroe to the Tower!

The match over, I was one of the tennis writers who flooded into the small subterranean room set aside for press conferences (a much larger, plusher space came along subsequently). It was chaos even before McEnroe showed up. In contravention of rules that kept broadcast interviews with players separate from press interviews, an American TV crew forced its way in and set up at the back of the room. Once there, it was impossible to remove them. There were just too many people.

One reason why the press numbers were so swollen was the presence, in addition to the tennis writers, of a large body of Fleet Street news reporters. The assignment of “rotters”, as they became known, to cover Wimbledon predated the McEnroe phenomenon, but he brought them out in big numbers. The wholly incompatible interests of the two constituencies were about to conflict disastrously.

For two or three minutes, harmless tennis questions were lobbed in McEnroe's direction: about his backhand, about his footwork, about break points won and lost. Warily, moodily, monosyllabically, McEnroe answered them.

Then, one of the awkward pauses between questions was broken by the unmistakable, pompous drawl of The Mirror's legendary royal reporter, James Whittaker, king of the “rotters”. Whittaker followed Lady Di everywhere and now the journey had brought him into direct contact with the biggest story in tennis. “John,” Whittaker asked, affecting a familiarity with McEnroe that was wholly bogus, “have you and Stacy split up?”

The atmosphere in the room was already quite toxic, and Whittaker’s question was like lighting a match. In the explosion that followed, McEnroe told us what he thought of us, flung back his chair and stormed out. His chaperone’s plea for “tennis questions only” came too late.

That was just the beginning. Arguments broke out between reporters. There was pushing and shoving. Chairs were knocked over. The room divided mostly along UK-US lines, with the American writers – serious tennis people – complaining bitterly that our low-down dirty gossip-trawlers had ruined things for everyone else.

The ugliest confrontation was between a tennis writer from The Mirror, Nigel Clarke, and a reporter from a US radio station called Charley Steiner. Some years ago I asked Clarke for his memories of the incident: “Everybody sort of gathered together,” he told me, “and the American guys were saying, why do you ask these kind of questions? And I said, we don’t preclude news reporters. They’re entitled to ask what they want. I felt Charlie was particularly abusive. I said, if you want to talk like that about it, let’s step outside! That's when it happened. I had the presence of mind to stand on a chair and punch downwards. But he wasn’t hurt, just a bit bemused.”

Steiner, who went on to work for the American sports channel ESPN, later recalled that “it became this international incident”. That was in part thanks to the unauthorised TV crew, whose pictures turned up on the BBC news. “My daughter saw it,” Clarke remembers with a shudder. “The BBC was describing it as disgraceful scenes. Oh dear!”

Bud Collins, then tennis writer for The Boston Globe and one of the most respected members of the tennis press corps, was in the room and saw matters from an American perspective. “I felt that Charlie was trying to defend American honour. He was tired of hearing all this 'Superbrat' stuff with McEnroe. He felt that one of his countrymen was being unfairly criticised. Then again, I don't know quite why he was so incensed. I saw the two of them on the floor and I was goggle-eyed. We're generally so helpful to each other. That's why I was shocked.”

Both Clarke and Steiner were summoned to the equivalent of the headmaster’s study, ie the office of the All England Club chairman, in those days the regimental figure of “Buzzer” Hadingham. Curiously, from their separate encounters with him, both men emerged feeling vindicated. Steiner said he was thanked and offered a cup of tea. “Wimbledon hated the tabloids as much as anyone else.” But Clarke says Hadingham told him that “he’d have done the same thing, but next time, old boy, do it in private”. That’s Wimbledon diplomacy for you.

Steiner and Clarke did not run across each other again for 15 years. “I was in Las Vegas in 1996, covering boxing,” Clarke recalled. “And across the room was Charley. We fell into each other’s arms and had a good laugh about it.”

In the years since that fracas, news reporters have become a completely accepted presence at Wimbledon, the gossip surrounding players as important to the news pages as the on-court action is to the sports pages. In the same press conference, the specialist tennis writer who wants to know about Roger Federer’s second serve might have to share time and space with the glossy magazine representative who wants to ask about Federer’s fear of dogs.

The arrangement has been known to create tension. “There's quite a bit of seething,” the veteran tennis writer Ronald Atkin told me. “The worst thing is when you get a player opening up on a subject in an interesting way and then someone jumps in and asks a question about something completely different. A good story can be throttled.”

Annabel Croft was a leading British player in the 1980s who now commentates on the sport. She endured some tough post-match press conferences of her own, including one which caused her to burst into tears. “I’d just lost to someone I felt I should have beaten, and during the match the umpire had wrongly accused me of swearing. It was all too much. I started crying and the press were very embarrassed. The questions stopped, and the reporters just quietly left the room.”

Croft sympathises with Osaka: “She needs to be helped along in terms of being able to do these interviews, and not to feel like the press and the media are her enemy.” But now that Croft is sitting opposite the players' podium and not on it, she feels that in the interests of maintaining tennis’s profile, even if it means the game turning into a bit of a soap opera, the press conference has an important role to play.

“I think back to Andre Agassi and his press conferences were amazing. He was so funny.” She cites Federer as the exemplary exponent of the press conference, a willing communicator who is patient and doesn’t rise to any bait. “He sees it as a way of reaching his fans.” And while many press conferences never stray beyond the formulaic, which is almost inevitable when the same player sits down in front of the press maybe hundreds of times, they can be revealing.

Croft recalls the time when the leading Canadian player Bianca Andreescu startled reporters at a press conference by discussing the role that yoga plays in her game. “Some players clearly enjoy the press conference experience,” Croft says, “but it’s not for everybody.”

It certainly wasn’t for John McEnroe back in 1981. And it wasn’t for Wimbledon either. Like the royal family, Wimbledon was used to being treated with deference. The concept of celebrity culture hadn’t fully taken hold, and everyone – supposedly – knew their place.

All that, however, was about to change, and the day that a John McEnroe press conference turned to mayhem looks very much like one of the moments when it did.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments