How mushrooms can save the world

Whether it’s removing oil spills in the Amazon or fighting pandemics, scientists are only at the tip of the iceberg in exploring how these organisms can heal the planet, writes Jack Dutton

Sonoma County was not spared by the 2017 California wildfires, which upended hundreds of communities and burnt down more than 1.5 million acres of land across the state. Scores of homes were destroyed as plastic and toxic chemicals permeated the air, devastating ecosystems and livelihoods.

Sonoma stood out because, unlike other counties, it used oyster mushrooms to help repair the damage. The grassroots Fire Remediation Action Coalition placed more than 56 miles of wattles – straw-filled tubes laced with the mycelium of oyster mushrooms – around the county. Mycelium, a threadlike, vegetative part of a mushroom, was able to help restore the natural habitats back to health. The wattles formed channels, diverting the toxic waste from unspoiled land to the fungi, which would digest it and convert it into nutrients.

There are an estimated 1.5 million species of fungi, many of which have inhabited Earth for more than a billion years. Although these organisms have been around for longer than humankind, scientists have barely scratched the surface in exploring their potential. A report released last week by The UK and Ireland Mushroom Producers Group outlines how mushrooms will be vital for the survival of our planet, whether it’s through restoring ecosystems destroyed by wildfires, facilitating nutrient cycles, capturing carbon or simply helping ensure a healthy and long life.

Wiping out plastic

It’s no secret that the amount of plastic we produce is spiralling out of control. Half of all of the world’s total plastic was manufactured over the past 15 years, and a study from May 2021 revealed that only 20 companies were responsible for 55 per cent of single-use plastic waste. Globally we produce around 300 million tonnes of plastic every year, and only 9 per cent of that is recycled. The rest takes about 400 years to break down, and each year, 8 million tonnes of it is dumped into our oceans, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). By 2050, there could be more plastic in them than fish.

Mushrooms can be the antidote to this problem. Some species of mycelium emit enzymes that break down hydrogen-carbon bonds in plastics, oils and other materials. Despite oil and plastics being toxic pollutants, decomposing it allows the fungi to break it down into nutrients.

A ground-breaking Yale study in 2011 discovered that pestalotiopsis microspora, a fungus in Ecuador, could digest and break down polyurethane plastic, even in an air-free environment – suggesting it could work well at the bottom of landfills. Later, in 2017, a team of scientists discovered another biodegrading fungus in a landfill in Islamabad in Pakistan. They found aspergillus tubingensis was able to break down polyester polyurethane (PU) – which is used in packaging foam – in the space of only two months.

Sehroon Khan, the scientist who led the team that discovered aspergillus tubingensis, has since found more than 50 species of fungi that can break down plastics and is researching which conditions this decomposition thrives in.

Slick operators

Mushrooms have also been shown to consume oil spills in a matter of days or weeks, via mycoremediation, the natural process that fungi use to degrade or isolate contaminants in the environment. Through a process called bioleaching, fungi have also been used to extract and recover heavy metals from contaminated water.

Harbhajan Singh, author of Mycoremediation: Fungal Bioremediation, tells The Independent: “There are studies out there in almost every part of the world, including in the US and Europe, where they are applying mycoremediation. So there is a good scope for this technology in the coming years.”

There is a new global network of people who are interested in fire and fungi that are emerging, and our hope is that we can develop methods that can be replicated and used all over the world

For 15 years or so, citizen scientists have used fungi to help clean up oil spills in the Amazon, boat fuel pollution in Denmark and petroleum from Californian soil. Oyster mushrooms are often used to clean up oil dumps, including from Chevron’s 350 petroleum wells in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Asked why oyster mushrooms have been effective on oil spills, Singh says: “They secrete enzymes in large quantities, and grow much faster than other mushrooms. Sometimes it takes eight weeks, sometimes a little bit more.”

“But one of the drawbacks here is the slow growth of fungi. So, to expedite mycoremediation, several exogenous nutrients or other compounds are added, so that growth can be enhanced,” he adds, noting that a mixture of sawdust and soybean hulls work as good substrates to speed up growth.

Mycoremediation is inexpensive, eco-friendly and effective compared with other ways of cleaning up oil spills. It has advantages over other clearing methods, which often involve digging up contaminated soil and incinerating it, emitting sooty smoke into the atmosphere.

Mushroom metropolis

Fungi can not only break down plastic – it can replace it too. Companies such as Paradise Packaging and UK-based Magical Mushroom Company are making mycelial packaging products that break down in a matter of days in your garden’s compost heap. Polystyrene, which is commonly used in packaging, never completely biodegrades. Fungi have tonnes of other uses too – businesses are building surfboards, clothing, boats, and even furniture out of mushrooms, all of which are more environmentally-friendly alternatives in a world consumed by fast fashion.

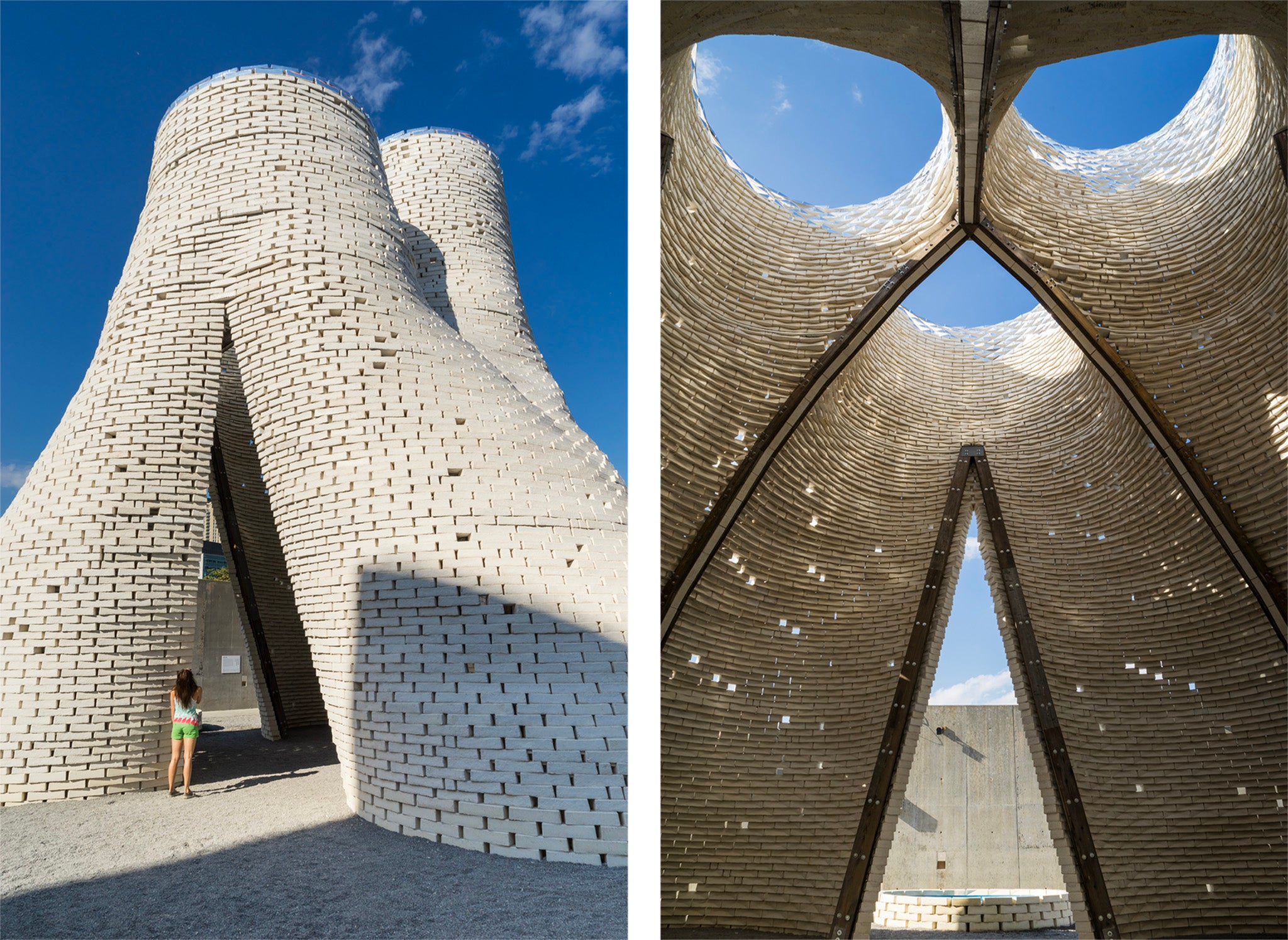

We can also make buildings out of fungi, instead of concrete, one of the largest culprits when it comes to carbon emissions. If the cement industry were a country, it would be the third-largest CO2 emitter in the world, behind only China and the US. The Hy-Fi, a 2014 project at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, saw a 13-metre tower being built from bricks made out of mycelium and agricultural waste. Hy-Fi’s bricks were grown in five days and, relative to their weight, were stronger than concrete. The structure was erected for three months before it was disassembled, with the remains being used as soil in local community gardens.

From steak to shrooms

Farming heavily contributes to our carbon footprint, and increasingly people are looking to cut down their meat consumption and turn to vegetarian or vegan options. Mushrooms are high in vitamins and nutrients, can reduce blood sugar and cholesterol, help us lose weight and lower our risk of developing cancer. There are growing numbers of mushroom-based alternatives to meat, which are packed with nutrients, such as vitamin D and B12, and can be seasoned to make them taste like meat.

As average global temperatures continue to rise, droughts and flash floods are set to become more frequent, destroying crops and farmland. Arable land will become a commodity as the climate warms, and many farmers believe vertical farming – done indoors in a controlled environment with crops growing on rows of shelves – will help shape the future of the industry. According to the OECD, agriculture contributes directly to 17 per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions, and an additional 7 to 14 per cent indirectly through changes in land use. Something needs to change quickly.

Mushrooms are perfectly suited to vertical farming because they don’t need lots of light to grow, which not only saves farming space but also reduces CO2 emissions and the need for pesticides.

Pesticides can alter the acidity of soil, killing off organic matter and stunting plant growth, allowing pests to flourish. They can also increase carbon emissions from farmland. Using fungi can help restore soil health and ecosystems, with some species – called entomopathogenic fungi – even eating bugs, acting as a natural, greener solution to insecticides.

Ecosystem engineers

Mycorrhizal fungi act as “ecosystem engineers”, and are critical to the natural world. The fungi help decompose organic matter, facilitate nutrient cycles and store carbon, developing soil structure and protecting plants so that farmers don’t have to rely on tilling or using chemicals to protect the soil.

These organisms are also used to repair ecosystems that have suffered major damage. The climate crisis has caused more wildfires, flash floods and drought. But global warming has also caused a dramatic decline in certain mycorrhizal fungi species, which are instrumental in connecting different lifeforms. Most of the carbon captured from the atmosphere by trees makes it down to the soil, where it is traded with fungal networks for nutrients, and often stored for thousands of years.

There are studies out there in almost every part of the world, including in the US and Europe, where they are applying mycoremediation. So there is a good scope for this technology in the coming years

Maya Elson is the executive director of CoRenewal, a company that designs filtration systems using fungi, bacteria and plants to reduce pollution in the Ecuadorian Amazon basin and the world. Elson is researching ways that mycowattles can help repair damage to ecosystems brought by climate change-related events like wildfires. These wattles are used to make mycofilters, which can biodegrade toxins running off the land before they contaminate waterways.

“We’ve been so far looking at wattle inoculation, and we’ve been supporting a study that's been done in partnership at UC (University of California) Riverside, that's looking at post-fire ecological regeneration with fungal inoculation and whole microbial community inoculation,” Elson tells The Independent.

“What we really want to do is bring both of those studies to the next level in a post-megafire environment, and see how we can achieve all of those same goals, also with a stronger focus on ecological regeneration and carbon sequestration post-fire.”

Stopping the next pandemic

For centuries, fungi have been used in medicine too. In the Netflix documentary Fantastic Fungi, leading mycologist Paul Stamets points out strains of fungi that possess molecules highly active against many poxviruses, as well as human papillomavirus (HPV). As scientists race to find the next antibiotic and prevent future pandemics, funders of scientific research need to appreciate the value of fungi. Over the centuries, they have been used to treat all kinds of illnesses – infections, viruses, heart disease and even mental health conditions like Alzheimer’s and depression.

Penicillin, the world’s first antibiotic, was discovered through a compound derived from fungus. So was cyclosporine, an immunosuppressant used for organ transplants. Fungal derivatives also help make statins and anti-cancer compounds, such as the chemotherapy drug Taxol, which was originally taken from fungi found in yew trees. Turkey tail mushrooms have also been shown to stimulate immune function in cancer sufferers. There is potential to treat mental health conditions too, with psilocybin – the active ingredient in psychedelic mushrooms – being found to help treat severe depression and anxiety.

Fungi are critical to vaccines too. Many vaccines – including Hepatitis B and more recently a Covid-19 candidate – are made using yeast. Researchers in the US found in July that a modular protein subunit vaccine candidate produced in yeast provided protection against Covid-19 in non-human primates. The results are promising, and potentially provide a low-cost vaccine for those in middle- and low-income countries.

Challenges

Despite the mass of evidence that indicates fungi could help promote a healthier planet, Singh says there are some obstacles when it comes to using them on a large scale – the main challenges being a lack of funding and awareness. The public, as well as businesses and investors, need to be better informed about the ecological and restorative benefits of fungi.

“Both mycology and mycoremediation should be given more consideration at university level,” Singh adds. “There are courses people take in those subjects, but still, I haven’t seen many mycologists or mycoremediation specialists coming out from the universities.”

CoRenewal is currently carrying out research into ecological restoration after the wildfires in California, but with more funding, it wants to expand its remit to include the wildfires in Oregon too.

“There is a new global network of people who are interested in fire and fungi that are emerging, and our hope is that we can develop methods that can be replicated and used all over the world,” she says.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments