Windsor and Murdoch: a marriage of convenience stretching back 100 years

Rupert Murdoch’s father, Keith, was a journalist who accompanied the then Prince of Wales on his first empire tour to Australia and New Zealand in 1920. Tom Roberts on the birth of an enduring love-hate relationship

In August 2005, the News of the World published a seemingly innocuous item of gossip. “Royal action man Prince William” had been left “crocked by a 10-year-old during football training”. The fact that this private information had been gleaned from a voicemail helped raise the first suspicions over the practice of phone hacking. Seven years later, as his news empire faced the dual threats of statutory regulation and competition with unfettered online media, a defiant Rupert Murdoch launched a return salvo.

He reportedly ordered The Sun to splash a far more eye-catching story involving another prince: “Say to Leveson, we are doing it for press freedom.” The next day’s front page was filled with a photo exclusive of William’s younger brother partying in Las Vegas under the headline: “Heir it is! Pic of naked Harry you’ve already seen on the internet”. (The clearly drunk, then third-in-line to the throne, was at least “covering his crown jewels with his hands”.) The Sun even parodied the traditionally sycophantic coverage of royal events and tours by stamping “Souvenir Printed Edition” across its masthead.

This mutually dependent love-hate relationship between the press and the palace, each needing the other for their own popularity, was nothing new. The connection between the houses of Murdoch and Windsor had begun 90 years previously. The players then had been Rupert’s father Keith and the princes’ party-loving great-great-uncle.

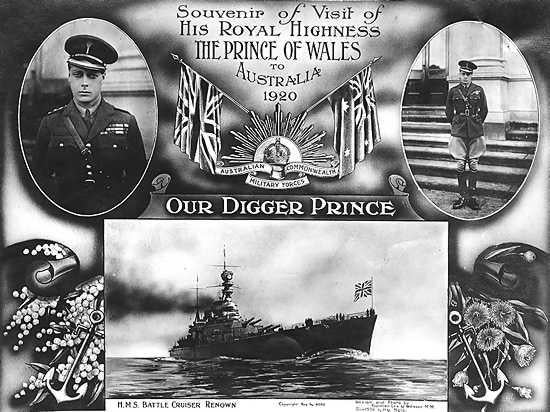

In 1920, Keith Murdoch served as one of the four official press representatives accompanying the Prince of Wales on his empire tour from Britain to Australia and New Zealand aboard HMS Renown. He supplied detailed coverage not only for the 250 newspapers taking the United Cable Service, which he managed during the First World War, but also for the press baron Lord Northcliffe’s Daily Mail and The Times.

Although Murdoch Sr’s participation in the tour has previously been overlooked and primary records are scarce, the plethora of articles he wrote provides a rich source. They are most useful in illuminating Murdoch’s ability to boost a cause and shape public opinion.

Following the long years of war and the fraught months of peace negotiations, the Renown’s voyage to the southern world was trumpeted as a mark of thanks to the people of the British Dominions. As with the wildly successful tour of Canada the previous year, it was hoped that fervour for the crown and the continuing bonds of empire would be reinvigorated. To this end, the newest communication forms and press techniques would be employed in a public relations operation capitalising on the celebrity of a cosmopolitan modern prince.

In his later years as the exiled Duke of Windsor, the former Prince of Wales recalled of the tour: “My job was to make myself pleasant, mingle with the war veterans, show myself to schoolchildren … cater to official social demands and in various ways remind my father’s subjects of the kindly benefits attaching to the ties of empire.”

His casual approach contrasted with the blunt view of the King’s private secretary at the time. Writing to the Australian governor-general, the private secretary emphasised the need for the trip to be taken as soon as possible after the troops returned from war. The governor-general had long feared a “weakening of the sense of dependence on the Mother Country and a fostering of Republican sentiment”. The prince’s visit, it was hoped, would prove an imperial tonic to allay any stirrings of discontent.

With the tour party readying to leave, Murdoch told his readers that this important mission to the southern world was being undertaken by a new type of prince: one who had embraced the new co-equality between the centre of the empire and its periphery. A decade earlier, Murdoch had privately dismissed the beastly humbug of archaic, London-centric royal pageantry: now he declared the prince was shaping a new role. Edward Windsor was not a mere symbol, “a stately puppet on a stately battleship”. Murdoch stressed to his readers: “He wants to know You. He wants to be friends among friends, to become just as much a part of Australian life as he is a part of British life.”

My job was to make myself pleasant, mingle with the war veterans, show myself to schoolchildren … cater to official social demands and remind my father’s subjects of the kindly benefits attaching to empire

Murdoch had prepared the public through a mounting public relations operation. His Royal Highness Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David of the house of Windsor (formerly Saxe-Coburg Gotha) had been rebranded as the “Digger Prince”, a “modernised, democratised Prince” for the people. The personalising process, drawing on Murdoch’s interaction with the royal personage, had started months before.

Writing in July 1919, almost a year before the Renown’s departure, Murdoch described the “Diggers’ Favourite” as “a pleasant youth”, still a boy at the age of 25. He had bonded so strongly with the Australian soldiers during his visits to the front that they had admitted him to the full comradeship of “diggerdom”. Under the headline “How the Prince became a Digger”, Murdoch detailed the royal embrace of Australian mateship. Fired with these happy memories, the prince had apparently confided to the journalist his desire to visit Australia.

To round out the framing of the persona Murdoch added tales of the prince’s passions for sport, animals, snappy dressing and a dash of romantic intrigue. The prince’s features might not have been “boldly handsome”, conceded Murdoch, but they showed an “engaging frankness” and “an honesty that suggests good firm character”. (A somewhat ironic judgement given the decisions he would come to make in life.) Murdoch detected that the prince – who would later force on his introverted, stammer-afflicted brother Albert the burden of the throne – was himself possessed of a “natural bashfulness … studiously suppressed”.

The 800-foot-long Renown, a “great white monster ... glistening clean” as Murdoch described the “wonder-ship”, finally set off from a cold and stormy Portsmouth on 16 March 1920. This was to be the most fully documented, photographed and filmed royal tour yet. Joining Murdoch and the three other press correspondents on board were the official photographer and a “cinema man”. The latter’s “topical reels” would eventually be spliced into a feature-length film, 50,000 Miles with the Prince of Wales, described by its recent cataloguer at the Imperial War Museum as “every bit as dreadful as its title suggests it might be”.

The tour was also to be the most rapidly disseminated in terms of news. With the advances in technology, updates could not only be cabled and wired but now radioed back and forth across large parts of the world, a situation contrasting markedly with the first royal tour mounted to Australia in 1868, four years before the completion of the Overland Telegraph Line. When unfortunate Alfred, “the Sailor Prince”, had been shot in an assassination attempt in Sydney, details of the incident took more than a month to reach London.

Murdoch was pleased to report that the prince “spoke of the coming voyage with pleasure” and was in a “buoyant and happy mood”. Edward wrote a different story to his mistress Freda Dudley Ward. He was already feeling in “a complete and devastating hell” at the prospect of the trip, and had beaten a hasty retreat to his cabin to sob.

Ever the advocate, if not always a practitioner, of meritocracy, Murdoch was keen to emphasise that the prince’s personal staff had been chosen “for quality of brain and character rather than for titles, wealth and favour”. Undermining his point somewhat, he identified the “Prince’s Special Chum” as flag-lieutenant Lord Louis Mountbatten – formerly Prince Louis Frederick of Battenberg. Noting Mountbatten was only 19, charming “and an exceedingly good-looking fellow to boot”, Murdoch predicted great things for him.

For this trip the latest developments in communication and entertainment technologies had been marshalled, both to keep the world informed of the Renown’s mission and to prevent the young prince from getting bored. Along with a printing press, a film projector had been installed, and Murdoch noted how the prince was “the most regular attendant at the ship’s bi-weekly cinema show”.

As the Renown ploughed on across the Atlantic, Murdoch was stirred by the power of one particularly modern form of immediate communication. He observed that the ship’s wireless operators were getting little rest, given the greetings constantly being “flashed” in.

A fortnight after setting off, the Renown reached its first official stop. As a local flotilla met the ship off Barbados in March 1920, Murdoch declared it “the greatest day in the island’s history since Nelson rid it of French rule”. He detailed how this “veritable bee-hive of negroes” contained “only 15,000 whites out of a population of 171,000”, with the black population “beginning to assert their claims of equality”. Issues of race aside, Murdoch was at pains to draw attention to the current deficiencies in technology and the need for investment: “As in other parts of the empire, the people of the West Indies are in desperate straits for communication with the rest of the globe.” A broken cable and an ineffective wireless service had meant the tour correspondents had to improvise.

Murdoch was doing his best to keep coverage of the tour constant and upbeat, but the prince himself was in desperate straits. Writing from Barbados, Edward confided to Freda Dudley Ward: “Christ! How I’m loathing this trip; there isn’t a single thing to it as far as I’m concerned as what’s the use of it all!!” However, there was a diplomatic utility to the unusual westward course taken. The colonial secretary had advised Lloyd George that a stop in the West Indies would help reaffirm the ties loosened by the war and serve to “most effectively discourage American aspirations in that quarter”.

Edward wrote a different story to his mistress Freda Dudley Ward. He was already feeling in ‘a complete and devastating hell’ at the prospect of the trip, and had beaten a hasty retreat to his cabin to sob

As March drew to a close, the Renown’s huge bulk was carefully navigated through the narrow cut of the newly constructed Panama Canal, only in its sixth year of operation. For Murdoch, the canal stood as a symbol of the great civilising achievement of man and industry that was now pushing back the jungle: a brave new world of technological innovation and control. In purple prose, he wrote of how a “swampy, fever-stricken, torpid place” had been reborn as the Canal Zone, “extremely clean, beautiful, healthy, peopled by robust and contented families, fed, clothed, exercised, educated by a paternal Government. All works smoothly. Such is the skill and organisation.”

The Renown’s stop at San Diego allowed the Californians to demonstrate their further skills for organisation – in this case for mass rallying aided by the latest technology with plenty of Hollywood pizzazz. The prince was driven through a ticker tape parade to the huge open-air City Stadium where 40,000 had gathered. With aeroplanes buzzing overhead and cameras snapping, the media circus was intense.

Murdoch recorded from his close vantage point that the prince had to deliver his speech with four film cameras “turning and snarling within a few feet of him, and with the huge horns of the magna vox in front of his face”. As an acute observer and agent of political communication, Murdoch was deeply impressed. Unsurprisingly for someone who found speech a constant struggle, he was also intimidated, predicting these “electric expanders” would inevitably make Australian public meetings “more terrible for the electioneer and the public speaker”.

Murdoch was also studying the Californian press, fascinated by their handling of the visit, the use of personalisation techniques and tabloid sensibility. For these correspondents, “The Prince was a ‘regular guy’, … a ‘democratic boy’, ‘like Cousin Ed. Home from the naval academy’.” But Mountbatten was incensed by another example of American press methods when an enterprising reporter, seeing the prince leave the dance floor for a few minutes, claimed to have conducted an interview. The account (“a masterpiece of fabrication!”), “duly appeared in the following day’s edition of the Sun”.

In Honolulu, there was a demonstration of an early form of paparazzi action. Murdoch described the scene in the jaunty vernacular style of his American colleagues, though he added ballast to his reports with some stern political commentary on the future of the Pacific region. His lengthy article, relayed across the Pacific “By Courtesy of the Naval Wireless Service”, and published 5,500 miles away the day after it had been written, related that the prince had been followed from the moment he landed by “four stalking cinematographers”, one of whom had chartered a boat in order to shadow the royal barge to shore. At first the prince had turned his back, but the photographer had pleaded with him: “Be a good fellow, Your Highness, this is my bread and butter!” and he had consented and posed with them, remarking that this was a good example of American persistence.

The ultimate PR opportunity for the prince’s party came with a visit to Waikiki beach where the prince made his first attempts at surfboarding and canoeing. The action footage, demonstrating more skill in filming from a parallel canoe than the prince showed with his surfing, took the prime slot in newsreels around the world.

But there was a political agenda too. While graceful natives danced a hula-hula to plaintive music, this struck Murdoch as “the swan song of this disappearing race”. The romantic scene he described added poignancy to a stark political point: “The Japanese in these islands now outnumber the natives by five to one … And the Japanese increase rapidly.” While the United States was spending “twenty million dollars on a great naval base” its government “scruples about preventing the free ingress of a people against whom the base is unquestionably directed”.

Murdoch was sure that the sensitive prince would see the poignancy of this. However, Edward told Freda that “the Hawaiian women who danced were too disappointing for words … though they knew how to wiggle their fat b—-s!”

On the trip down towards Fiji, the prince was again “terribly depressed: everything looks so inky black ahead of me; starting real hard work again in NZ & Australia, which I’m dreading more than I can say”. He confided to Freda: “Who knows how much longer this monarchy stunt is going to last or how much longer I’ll be P of W?” According to Murdoch, however, the prince was looking forward “with boyish eagerness” to seeing the people of New Zealand and Australia.

The prince was again ‘terribly depressed: everything looks so inky black ahead of me; starting real hard work again in NZ and Australia, which I’m dreading. Who knows how much longer this monarchy stunt is going to last’

The Times’s lead editorial on the prince’s safe arrival at Auckland praised “Our Special Correspondent” and his “glowing account of the hearty enthusiasm with which the Heir to the Throne was received”. It emphasised the power of the pressmen in making the effect of the Dominion tours empire-wide and not just local: “Publicity is of the essence”. In his own comments, Murdoch pointed to another key position. Just as important as the 90 uniformed policemen and Scotland Yard bodyguards protecting the prince was the manager of the telegraph department, who “accompanies the pressmen to secure the promptest despatch of their messages”.

The pre-publicity operation had worked beautifully. Edward wrote privately of the huge, though “amazingly respectful”, crowds: “they always call me ‘Digger’, which is the highest compliment they can give me!!” During the tour of New Zealand that followed, Murdoch’s coverage took a distinctly saccharine turn. Front pages carried the expected stories of posies and flags, visits to injured soldiers and dances with pretty local girls. But Murdoch was also on the lookout for the personalising aside or unexpected moment that humanised the prince, in contrast to the pomposity of the official welcomes and endless speeches. The tale of Prince Charming coming to the aid of a “lame girl” having trouble taking a snap of him with her new Kodak was typical.

The sheer volume of Murdoch’s reports was phenomenal. Of the 80 paragraphs of text on the front page of the 27 April edition of The Herald, 75 were attributed to or directly relayed by him, and this was even before the prince had reached Australian shores. Embedded in the reams of print were some wry asides about the whipped-up enthusiasm. Murdoch mused on whether one rural town was “going to follow the example” set by another “and parade even its lunatics in the street” during its welcome pageant.

Just three days into the North Island leg of the New Zealand tour progress was derailed. A strike by the Locomotive Drivers’ Union and the sabotage of the pilot train left the tour party “Marooned in Maoriland”. While Edward was reduced to playing golf and otherwise “twiddling his thumbs”, Murdoch used the time to type a contemplative piece on modernity and the new order of things to come. He described that a group of Maori chiefs had presented the prince – who was decked out in his eponymous grey checked suit and Guards’ tie, “every inch of him” speaking of “clean British manhood” – with one of their “few remaining racial heirlooms”.

Murdoch claimed the old chieftains “knew of the contrast in that room and accepted it, bending low in obeisance to the fair-skinned and fair-eyed youth, eldest son of that great race whose sword had conquered their bodies and whose ploughs, wheels, schools, and laws had conquered their minds”.

Time for such wistfulness and reflection was suddenly removed with the abrupt end of the strike. The tour party left the station at night without public notice, and so only the railwaymen – whom Murdoch described as now “eager to show their loyalty to the empire and their friendliness toward the Prince” – and “their girls” were there to give “a warm send-off”. Harking back to the American newspaper coverage of a month before, Murdoch was keen to personalise the scene for his Australasian readership. He relayed how one man called out “Hope we didn’t disturb your arrangements too much, sir?”, while the girls cooed “Isn’t he a peach … Fancy him walking, he’s just like one of us.”

More than the railworkers and their girls could dare imagine, the prince wanted to be just like one of them. Writing to Freda, Edward declared “the day for Kings & Princes is past”. The Prince of Wales, heir to the Imperial Crown, began signing his letters with the moniker “Bolshie David”.

Unaware of this, The Herald’s front page of 5 May boomed “The Prince’s Great Triumph”. The page also held a small article which was, for once during the tour, written by someone other than Murdoch. A parallel triumph was trumpeted under the headline “‘Brilliant Journalist’: Tribute to Mr K. Murdoch”. Illustrated with a photograph of Murdoch, the report relayed the praise heaped on him, as official correspondent of the tour, by dignitaries at the Australian Natives’ Association dinner in London.

Glasses might have been raised in toast to Murdoch’s name in the Mother Country, but he was receiving rougher treatment in left-leaning Antipodean newspapers. “Mr Keith Murdoch’s Lie: The Method of the Capitalist Press” ran one New Zealand headline above an article challenging the account of the rail strike. His tour coverage was attacked as being columns of “sycophancy and snobbishness” beneath “fantastic headlines”. More lighthearted yet still cutting criticism came from across the Tasman. The Sunday Times in Perth composed a special verse, “The Hapless Prince”, in honour of Murdoch and his colleagues, asserting that Australia owed a lot to these gifted chroniclers and assiduous gatherers of princely personalia:

In their repertoires there’s scarcely a superlative remains,

Scarce a wire but drips with treacle that they shed,

The most-trivial occurrence sets them racking of their brains

To put another halo round his head.

Murdoch was scarcely immune to criticism from the other end of the spectrum either. Mountbatten recorded that there had been private complaints about a long article headed “The Unpunctual Prince” that blamed the prince for always being late. The tour leaders were furious that such insinuations should be made against HRH “by one who has been an honoured guest on board throughout the trip”. Murdoch was absolved after explaining – somewhat disingenuously – that a local correspondent should be blamed. However, the nickname stuck, rankling so much that three decades later the now Duke of Windsor recalled bitterly that each delay in the tour’s schedule had added “to the growing legend of the Unpunctual Prince.”

On 26 May 1920 the royal party stepped onto the Port Melbourne pier before a grand procession led by two state carriages progressed through the city. Mountbatten thought the “motor cars containing the press correspondents” bringing up the rear “looked very incongruous and out of place”. However, the scale and mania of a crowd estimated at 750,000 – evidence of a PR job well done – meant that Murdoch could feel secure in his status.

Murdoch told his Times readers that the throngs of well-wishers were unprecedented – though “possibly you are tired of reading about them!” Yet for Murdoch the “most impressive sight” of the whole tour came with the drill display mounted by 10,000 children at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. It was “a brilliant spectacle, resembling those modern pictures whose effect is obtained by the assembly of a myriad of infinitesimal dots of colour”. He was stirred not only to thoughts of art and pointillism but to visions of military precision as “this army of children” moved to the sound of the trumpet “with the ordered discipline of veterans”. It was not simply the children’s good behaviour that struck Murdoch, however. The man who would later be drawn to eugenics observed: “The great majority were fair-haired, witnessing that they were probably of the purest Anglo-Saxon stock in the world today.”

Discipline, organisation and order might have been on display in the massed ranks of the dominion’s children, but their golden-haired prince privately felt so stale that he had “ceased to worry now” about the tour. Edward told Freda: “[I] just drift along from minute to minute & hardly ever look at the programme & often haven’t the least idea of where I’m going … Thank God!”

Already drunk after attending a 12-course naval dinner served at a table shaped like a boomerang, he had drifted along to a smoke social at the Grand Hotel. The event provided an opportunity for Australian journalists to meet their British colleagues accompanying the prince. As Murdoch would be peeling away from the tour now, the social also toasted his achievements as an official correspondent. One editor waxed on how “Keith Murdoch belonged to a younger generation of journalists, and he was known as a man who would go far, although, perhaps, it was never thought that he would ‘live to mould a mighty State’s decrees and shape the whisper of a throne’. (Laughter) But he did it!”

This text is an extract from ‘The Making of Murdoch: Power, Politics and What Shaped the Man Who Owns the Media’, by Tom Roberts, and published in hardback by Bloomsbury

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments