‘We were all terrified’: How a horrific murder can haunt a town

A brutal killing in the community seeps into the psychology of a place and its people, writes James Rampton, as a new series explores how 10 British towns coped with tragedy

The towns of Soham, Dunblane, Hungerford and Lockerbie all have one very sad fact in common: many years after the event, they are all still best known as the scenes of heinous crimes.

How does a horrific murder affect a tight-knit community? Is the town where it took place forever scarred? In the aftermath, are neighbours perpetually mistrustful of each other? And do people always see the location in a darker light?

These are the profound questions explored in Murdertown, a new TV series which starts on Monday. It offers an in-depth investigation into the far-reaching ramifications of a single murder in ten different British towns: Milton Keynes, Wakefield, Wigan, Wishaw, Southampton, Oxford, Lichfield, Leicester, Bath and Whitby.

In each episode, the presenter, Anita Rani, visits a town where a brutal killing took place to recount these tragic episodes through the testimony of family, friends, investigating police officers and local journalists. These are people whose lives have been irrevocably changed overnight by one horrendous event. In an instant, they are living under a dreadful, brooding shadow.

Joel Orme, the series producer of Murdertown, begins by underscoring how a town can become irretrievably tarnished by a particularly savage murder. “One of the best examples is Wishaw, where 17-year-old student Zoe Nelson was killed in May 2010. It’s such a small place. I remember talking to a local police officer who said, ‘we are only known for two things: the snooker player John Higgins, whose nickname is the Wizard of Wishaw, and the murder of Zoe Nelson. We’re a tiny community and all the industry here has basically gone, so all people remember us for is a horrible murder and a snooker player with zero personality. That is what we are defined by. It’s sad, and it’s a hard image to shake’.”

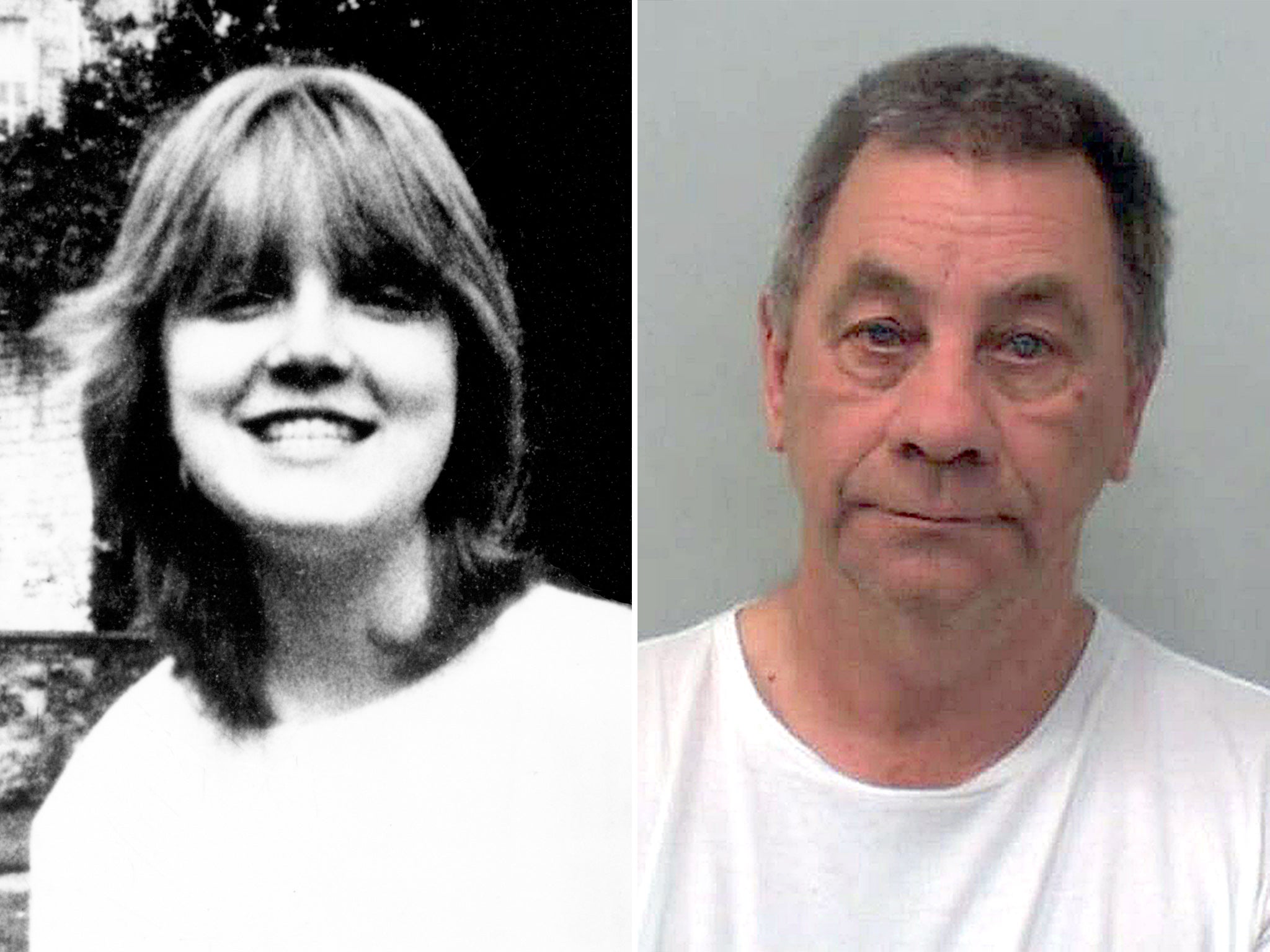

That taint is not restricted to small towns, though. It also affects larger communities still haunted by an especially grim murder. The series producer cites the example of Bath. In 1984, 17-year-old Melanie Road was killed on her way home from a nightclub. Her murderer, a married father called Christopher Hampton, was only caught 30 years later, after huge advances in DNA technology. “Bath is this beautiful town,” Orme says. “It’s got so much history and architecture. The crime that happened there was particularly grubby and horrible. The residents were very aware of how that affected the image of the place. It took 30 years to solve that murder, so it was hanging over the town for a long time.”

Orme goes on to reveal his own connection with a murder which traumatised a small community. He grew up in a small village near Wigan called Appley Bridge, where, in 1995, 15-year-old schoolgirl Louise Sellars was murdered. In an appalling twist for her family, the murderer, a local man called Darren Ashurst, was not apprehended for another five years. This shocking story features in the new series of Murdertown.

“When she was murdered, Louise was only a couple of years younger than me,” says Orme. “I spoke to my mum about it recently and she told me, ‘I remember it so well. We were all terrified.’ The whole village was basically on tenterhooks because this girl was killed in quite a brutal way. Nobody knew who the killer was, but we knew it could be someone living within this small community. Our parents were all petrified. Now I’m a parent, I can totally get how fearful my mum and dad must have been at the time.”

“I have a friend called Sam Thompson, who is a couple of years younger than I am,” says Orme, speaking of his link to this tragic even. “He was 15 or 16 at the time of the murder and was very much part of the group of teenagers that used to hang around on street corners and in the park. He knew Louise pretty well. He was quoted in her diary, questioned by the police at the time and had his DNA taken. I asked him what it was like to be questioned by the police and he said, ‘even though you know you've done absolutely nothing wrong, you can't help but be terrified.’”

She said that about a month after Wendy disappeared, when it was still a missing person’s case, she was chatting to Salisbury, the eventual killer

Thompson’s evidence, however, did help build the case against Ashurst. Orme carries on: “On the night of the murder, Sam and his three friends were walking back home when a white car swerved towards them and then swerved back to the right side of the road and continued on. The belief is that was the killer in the car with the girl. When she spotted these boys she knew, she tried to grab the wheel and get their attention.”

One particularly disturbing aspect of this story highlights the deep sense of mistrust that can be seeded in a local community after such a hideous crime. Ashurst defiantly stayed on in Appley Bridge for five years after committing the murder. Rani, who also presents Countryfile and Woman’s Hour says, “that brazen attitude was absolutely horrendous. Because he thought he had got away with it, that guy felt he could just go back there and carry on regardless. I don't know how a person's psychology could allow that, but then I don’t understand how he could have killed her in the first place. So when a crime is committed in a neighbourhood and someone local is suspected, it can absolutely sow mistrust.”

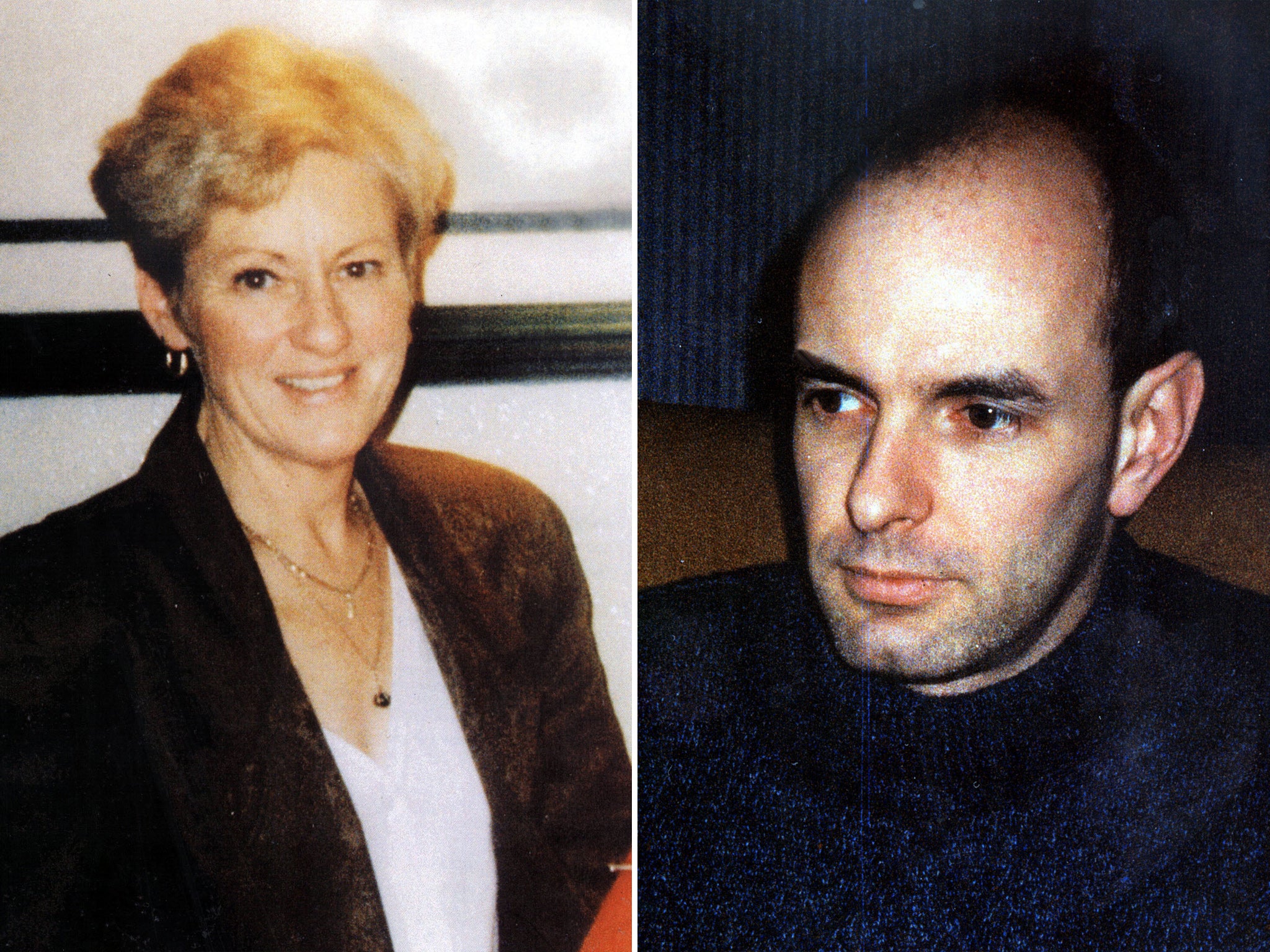

That sense of suspicion was also apparent in the wake of the murder of Wendy Upton by Steven Salisbury in Lichfield in 1998. “It’s one hundred percent more disturbing when the murderer is someone you know, someone you’ve seen every day,” Orme says. “For the Lichfield episode, we spoke to the victim’s next door neighbour. She said that about a month after Wendy disappeared, when it was still a missing person’s case, she was chatting to Salisbury, the eventual killer. He jokingly said to her, ‘oh, you know who I am. I’m the guy who murdered Wendy Upton.’

“It seemed like gallows humour, but the reality is, he was trying to deflect attention away from himself. It was really disturbing that he could laugh about it, make light of it and use that friendship to do that. That woman and Salisbury only lived across the road from each other. She was very upset about that. Looking back, she said, ‘how dare you say that to me, knowing I'm her friend?’”

Orme goes on to consider whether a community can ever get over such a trauma. “I don’t think they necessarily can. As long as there is a generation of people in that village who lived through it, it will always be remembered. I had a Zoom recently with some friends from Appley Bridge and mentioned that we were covering the Louise Sellars case in Murdertown. Everyone went, ‘oh yes, I remember that very well’. It will always be remembered because it’s such an unusual thing to happen in a place where you live. Time will be the only thing that dilutes that memory.”

These crimes, of course, also have a seismic effect on the family and friends of the victim. Murdertown, for instance, features a moving interview with Tracey Millington-Jones, the daughter of Wendy Speakes, who was murdered in Wakefield by Christopher Farrow in 1994. Eventually convicted thanks to fingerprint evidence in 2000, Farrow was sentenced to a minimum of 18 years. Millington-Jones continues to lead a so-far successful campaign against his release from prison. Orme says, “it was really, really strong of Tracey to take part in our programme, but she took part for a reason – to make sure Farrow stays in jail.

“We said to her, ‘absolutely, if you tell us your story, we will give you the platform you want to be able to raise awareness of what is obviously a very important campaign.’ I think it’s important not just for her, but also for the people of Wakefield. When we interviewed locals for that episode, everyone bent over backwards to accommodate us. Because all these people still live in Wakefield, and none of them want to see this guy back anywhere near the town.”

The interview with Millington-Jones was an emotional affair. “Within two minutes,” Orme says, “Tracey was crying. By the end of it, all three of us in the room were exhausted, but it felt like a massive sigh of relief. Once it was done, she was so pleased and so grateful she’d done it. For her, there’s a certain level of catharsis in talking about it as well because it helps her overall desire to keep this guy in jail, but also because in talking about it, she can help with her recovery.”

Those close to the victim of an awful murder in Milton Keynes were similarly damaged. Rachel Manning was killed on her way home from a nightclub in 2000. Her boyfriend Barri White, apparently the last person to see her alive, endured an atrocious miscarriage of justice when he was wrongfully convicted of her murder. After five years in jail, his conviction was finally quashed in 2007. In 2013, Rachel’s actual killer, Shahidul Ahmed, was convicted on DNA evidence.

White also spoke to Orme for Murdertown. According to the series producer, “those five years for Barri basically defined his life. He has been through various different drug rehabilitation programmes. He can’t hold down a job, and he can’t hold down a relationship. He started to get help about 18 months ago, but says he wishes he’d got it so much sooner. For ages, he said, ‘it’s fine. I can do this on my own. I’ll be okay.’ But the reality was that he wasn’t okay.

When you go to these quiet, picturesque British towns like Whitby, which is one of my favourite places to visit on earth, some people definitely remember these horrendous crimes

“Until Ahmed was convicted, Barri said there was very much an element in Milton Keynes of, ‘you’re very lucky to be out of jail. You definitely did it’. So although he was completely exonerated and his conviction was quashed, when he went back to Milton Keynes, he very much felt like half the town was against him and still believed he was responsible. It was only when the real killer was caught that he could finally relax a little bit.”

Even so, “when Barri came for the interview with us, he brought a friend along. We shot it during fairly strict lockdown conditions, so it was quite difficult. He asked, ‘can I bring a friend to the interview?’ We said, ‘well, you can, but they can't be in the room with you.’ And he replied, ‘that’s all right. I just need someone to know where I am.’ So basically, wherever he goes, he takes someone with him because he feels like he always has to have an alibi. Which is so sad.”

Like Millington-Jones, though, White ended up finding the experience of talking about it therapeutic. “At first,” Orme says, “he was very resistant to being involved. We went back and forth with him. Eventually, he said, ‘let me go and speak to my therapist.’ That was the key moment. The therapist said, ‘I think you should do the interview. I think it’ll actually help you. You’ve spoken to me about it, but you don’t speak to your friends and family about it. Maybe getting it all out will be a good thing for you.’”

All the same, the long-term harm caused to White is undeniable. He is another victim in this murder case.

“Because of the miscarriage of justice, this is a particularly tragic story,” says Rani. “Barri White’s life is ruined. He will never be able to live the life he wanted because he wrongly spent five years in prison. This story really stays with me for that reason.”

Murdertown plays into our current passion for true crime stories. Rani assesses why the genre is so popular at the moment. “We all love to solve puzzles. We all like to become investigators and try to figure out these cases. We also like watching these programmes from the safety of our own home. That makes us feel comfortable. We all want justice, too, and thankfully in this series, there is justice.

“We are all fascinated by the dark side of humanity as well. We’ve all been brought up with stories of goodies and baddies. This series taps into something in all of us that fascinates us – how can one human being do such a dreadful thing to another? What makes one human being capable of doing something as horrendous as taking another human being’s life?”

The series also gives us pause to think how we might respond if our community was affected in this way. “I think it’s definitely relatable,” says Orme. “It carries that whole idea of, well, if that happened there, it can also happen here. And if it happened here, how would we feel? How would we react? There are elements of an audience plugging into that and sympathising with the people affected. If you’re watching a documentary about a murder in a place like Wigan or Wakefield and you’re a viewer in Bolton or Blackpool, you’re basically seeing a mirror image of where you live.’

But above all, Murdertown aims to honour the murder victims who are too often neglected. “We wanted to talk about victims whose stories should be heard and not forgotten,” Rani says. “These communities are devastated by what has happened to them. Families can never go back to what they were. Parents who have lost daughters can never be the same again and friends who have lost friends will be impacted forever.

“When you go to these quiet, picturesque British towns like Whitby, which is one of my favourite places to visit on earth, some people definitely remember these horrendous crimes, but 20 years later, most people are just getting on with their lives. So it felt very important just to remember the victims. I hope we are showing family members that their relatives are not forgotten. I don’t think they will get closure, but maybe they might be able to move on a little bit. They might find some kind of solace in the fact that their story is being told and that their relative is being remembered.

“There tends to be so much focus on the murderer. Let’s talk instead about the people whose lives were so cruelly taken.”

Murdertown begins on Crime + Investigation at 9pm on Monday 27 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments