Monty Python at 50: A celebration of something completely different

The British Film Institute is marking this comedic landmark with a series of treats, from feature films to documentaries and home movies. But the best bits, as William Cook discovers, are the shows that came before. So where did it all begin?

On Sunday 5 October 1969 at 11pm (after most respectable people had gone to bed) the BBC broadcast the first episode of a show that changed the course of British comedy. Monty Python’s Flying Circus was unlike anything we’d seen before, and now, 50 years later, the British Film Institute is marking this comedic landmark with a spectacular birthday party.

Throughout this month the BFI is screening all sorts of Python treats, from TV shows to feature films, from documentaries to home movies, but the most intriguing elements are the shows that came before. Although Monty Python was revolutionary, it didn’t happen in isolation. It grew out of numerous strands in postwar British comedy, and it’s these strands which make Monty Python at 50 more than just a rerun of greatest hits.

So where did Monty Python’s Flying Circus begin? Probably the biggest influence on Monty Python was The Goon Show, that absurdist radio series written by Spike Milligan, and performed by Milligan, Peter Sellers, Harry Secombe and (briefly) Michael Bentine. The Goon Show and Milligan’s TV series, Q5, both feature in John Cleese and Michael Palin’s Pick of Python Influences, a key part of this season.

Another big influence on Monty Python was Beyond The Fringe, that taboo-busting stage show performed by Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett and Jonathan Miller, which sent up every aspect of the British Establishment, from the clergy to the monarchy – ending the age of deference and launching the Sixties satire boom. Cook and Moore’s subsequent sketch show, Not Only… But Also, has been selected by John Cleese as an inspiration.

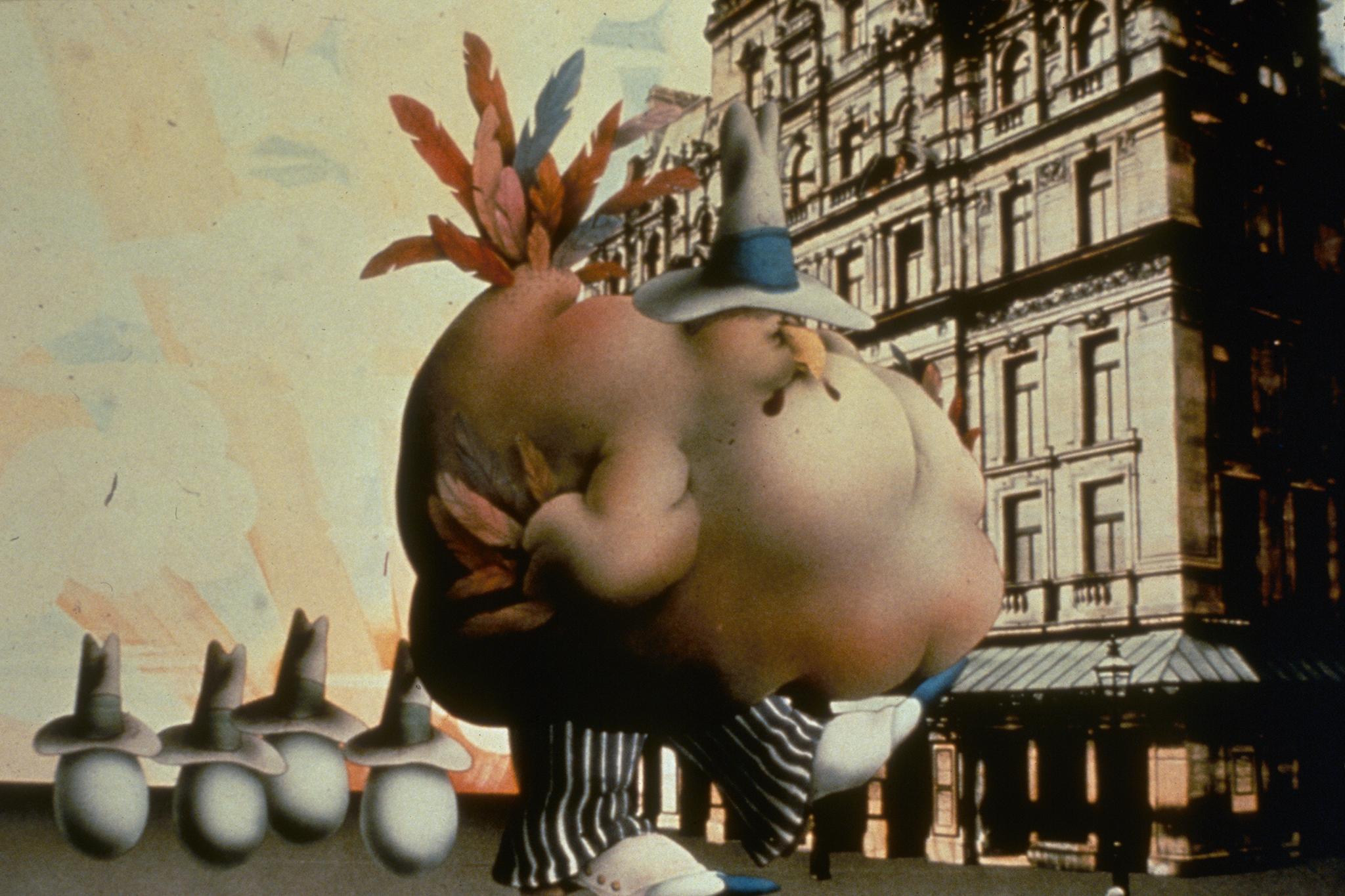

But Python wasn’t just a British ensemble. True, five of the team were British, and all Oxbridge graduates to boot (Michael Palin and Terry Jones met at Oxford; John Cleese, Graham Chapman and Eric Idle all met at Cambridge) but the sixth member, Terry Gilliam, was American, and it was his bizarre animations which gave the show its definitive aesthetic.

Born and raised in America, Gilliam’s influences were a world away from Oxbridge. One of his inspirations was the surreal visual gags of American comic Ernie Kovacs. Kovacs’ life was cruelly cut short when he died in a road accident in 1962. This month, to mark the centenary of his birth, Gilliam is introducing a selection of highlights from Kovacs’ career.

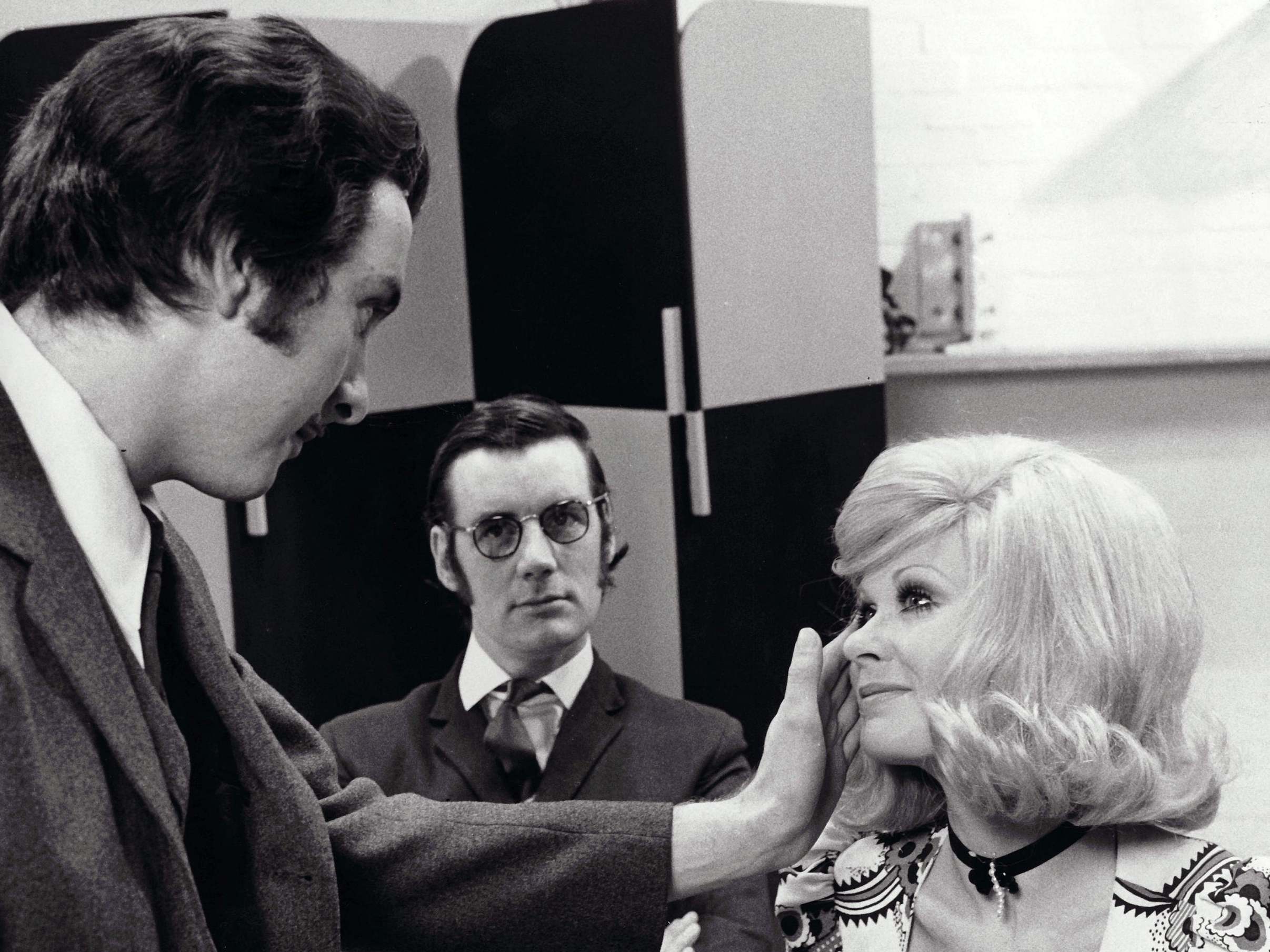

Even more important were the TV shows the Pythons made before they became Monty Python. You can see two of them in this season: At Last the 1948 Show and Do Not Adjust Your Set. The 1948 Show was a sketch show written and performed by Cleese and Chapman (with Marty Feldman, Aimi MacDonald and future Goodie Tim Brooke-Taylor). Do Not Adjust Your Set was a children’s show featuring the other four Pythons (Idle, Jones, Palin and Gilliam) and the wonderfully silly Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band. “It was a dress rehearsal for Python,” says Neil Innes, a member of the band who went on to work with Python on TV, onstage and in the movies.

At first it may seem surprising that two-thirds of Monty Python, a late night adult TV show, should emerge from a programme specifically designed for kids. However, when you stop and think about it, it makes perfect sense. One of the main elements of Monty Python was its childlike sense of fun. Although it was billed and scheduled as a children’s programme, Jones, Palin, Idle and Gilliam never set out to make comedy for children. They simply did what they thought was funny. Consequently, although kids loved it, the show also attracted an adult audience, including Cleese and Chapman, who used to stop work early whenever it was on, so they could watch it. “We were all very close to childhood,” says Innes. “We knew nothing about children’s television, other than having fun, playing games and imagining things.”

So who brought these two shows together, and turned them into the most extraordinary show in the history of British comedy? Well, it was Cleese who made the first approach to the Do Not Adjust Your Set team (he’d already worked with Palin on a one-off sketch show called How to Irritate People) but it was Barry Took who approached the BBC on their behalf.

Barry Took is now best remembered as the presenter of TV’s Points of View (in which pedantic viewers wrote in with nit-picking complaints and queries) but off-camera he was a far more significant figure, the creator (with Mary Feldman) of the classic sitcom Bootsie & Snudge, and a key player in the development of British comedy. Took approached the BBC about Monty Python and even though the Pythons didn’t have a clue what they’d put in it, the BBC (to their eternal credit) commissioned 13 programmes. That was in the good old days when BBC executives trusted the talent. They didn’t micromanage, so the Pythons had the freedom to experiment. It was this freedom which enabled them to create such an innovative and unusual show.

What made it so special? Well, the absence of punchlines, for one thing. Ever since the days of Music Hall it had been a comic axiom that sketches had to end with a big closing gag to bring down the curtain. A lifetime later, on TV, that old-fashioned orthodoxy prevailed. Even Peter Cook and Dudley Moore clung to this convention in their otherwise progressive sketch shows, often ending a brilliant sketch with a lame one-liner.

The Pythons weren’t the first to notice that punchlines were a curse, but they were among the first to dare to ditch them. Spike Milligan was the very first (his Q5 series was broadcast while Monty Python was in production – a sign that change was in the air) but the Pythons found a far neater way to segway from one sketch into another. Gilliam’s crazy cut-ups could bridge the gap between any two sketches, however incompatible. You simply told him where to start and where to finish and he filled in the rest. That clumsy compere’s link, “And Now for Something Completely Different”, was rendered utterly redundant. Instead, it became their catchphrase.

Carol Cleveland was hired to be a “glamour stooge” (as she describes it) in the first series. “I don’t think this is going to last very long,” she told her husband. She subsequently appeared in 30 episodes, all four Monty Python movies, and performed with the Pythons onstage in the UK and the US. Yet she recalls being utterly mystified when she first read the script. “I don’t get it,” she thought, but when Gilliam’s animation filled the gaps, it all came together. “It was only when I saw the animation and how it actually fitted in that I realised how this show was linked together,” she remembers. “One thought just drifting into another, like a stream of consciousness.”

But there was more to it than a lack of punchlines and Gilliam’s zany flights of fancy. The performers were a perfect blend. Cleese played the authority figures, Idle played the cheeky chappies, Palin was lovable, Jones was intense. Chapman was superb at playing decent, beleaguered everymen (a role he perfected as King Arthur in Monty Python & the Holy Grail and Brian in The Life of Brian). Gilliam played the manic, guttural grotesques. Carol Cleveland also gave the show something extra, especially on TV. “I wasn’t just a pretty face – they realised I could be funny in my own right.”

Before the first live recording, the Pythons had no idea whether anyone else would find it funny, but they didn’t really care. Thankfully, they didn’t try to second guess their audience. They simply set out to amuse themselves. “They were like schoolboys, larking about,” recalls Carol.

This wasn’t just a winning formula on the small screen. It also worked really well onstage, as Neil Innes discovered when he performed with the Pythons at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, in London’s West End. “Drury Lane was an extraordinary success,” he says.

But above all, it was all about the quality of the writing. The Pythons always saw themselves as writers first and performers second (before they teamed up, only Cleese was a famous face, as opposed to a familiar byline, on account of his appearances alongside Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbett in The Frost Report). This meant when it came to casting, the success of the sketches was always paramount. The power struggles were always about which sketches made the final cut, rather than who got to play which part.

As with the performing, there was great variety in the writing. Cleese and Chapman generally wrote together, as they had done since university. Likewise Jones and Palin. Idle usually wrote alone. Like The Beatles, to whom they’re often compared (and to some extent resembled) this resulted in a range of styles, from several diverse sources. Cleese and Chapman tended to write more wordy sketches. Jones and Palin were more interested in character. Idle’s sketches were more conventional. His Nudge Nudge, Wink Wink sketch was originally written for (and rejected by) The Two Ronnies.

The Pythons had no idea whether anyone else would find it funny, but they didn’t really care. Thankfully, they didn’t try to second guess their audience. They simply set out to amuse themselves. They were like schoolboys, larking about

And then there was the music. Everyone remembers Idle’s “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life” but there are loads of other classics (“The Galaxy Song” from The Meaning of Life; “The Lumberjack Song” from the TV series). It’s not easy to write a song that everyone can still sing along to half a century later. No wonder George Harrison was such a fan. It was thanks to him that Life of Brian went ahead – he mortgaged his home to make it.

The other thing the Pythons recognised was that being avant-garde was no excuse for being lax – quite the opposite, in fact. They were never afraid to criticise each other’s work, cutting (or even axing) each other’s sketches. The result was far tighter – and invariably funnier – scripts. “Cleese is one of the most brilliant analytical comedy brains – maybe it’s studying law that teaches you this,” says Innes. (Cleese read Law at Cambridge.)

That intellectual rigour was something all the Pythons shared. When they were writing for other people’s shows, TV executives would often veto their more esoteric suggestions. “They’ll never get it in Bradford,” would be the patronising response (TV execs always underestimate the collective savvy of the viewing public). Free to do whatever they wanted, with only the other Pythons to answer to, they proved that viewers in Bradford (or wherever) were perfectly capable of getting it. ”The Pythons didn’t dumb anyone down, they brought them along – they didn’t treat people as idiots and people got it, and I think they respected the fact that they weren’t being treated as idiots,” says Innes. “They assumed their audience was intelligent.” And they were right.

Today the term Pythonesque has entered the English language, yet this remarkable TV show (and the films and books and records that sprang from it) might quite easily have never been called Monty Python at all. For a long time it had no name because the team couldn’t decide on one (A Horse, a Spoon and a Bucket, Owl-Stretching Time and The Toad-Elevating Moment were just some of the numerous working titles). Eventually BBC execs started calling it Barry Took’s Flying Circus (Flying Circus was RAF slang for balls-up) simply as a reference point in their internal memos.

The Pythons didn’t dumb anyone down, they brought them along – they didn’t treat people as idiots and people got it, and I think they respected the fact that they weren’t being treated as idiots

The Pythons liked the Flying Circus bit (although it confused a lot of viewers) and eventually settled on Monty Python – thinking it sounded like a seedy impresario. It almost became Gwen Dibley’s Flying Circus, after a woman whose name had caught Palin’s eye. This could have posed a legal problem, so Monty Python triumphed. Just think: if Palin’s suggestion had prevailed, we might well be describing stuff as Dibleyesque instead.

Even though most people still regard Monty Python as quintessentially British (despite Gilliam’s unique input), it was the show’s success in America which gave it proper staying power. “The Pythons had doubts – they didn’t think it would work there,” says Carol. Their worries were unfounded. If anything, Monty Python became even bigger in the States.

Because there was no video in those days (let alone Netflix or YouTube) the shows were hard to track down, so the Python LPs became very popular. These albums attracted a cult following in the States, often among people who’d never even seen the TV shows. When the Pythons toured America, they were treated more like rock stars than comedians. The BBC shows were then shown ad infinitum on PBS, America’s public access TV network, meaning American viewers saw them a lot more often than British viewers back in Britain.

Buoyed by this exposure, they played Broadway and the Hollywood Bowl. Carol likens these shows to pop concerts, full of screaming fans. “Everybody was standing up, cheering and shouting – we could hardly get a word out.” One of the main talking points in America was their fondness for wearing women’s clothes. “They didn’t do drag in America in those days. I think that was the first thing that stuck out there, the fact that these men dressed as women.”

Graham Chapman’s untimely death in 1989 (from cancer, aged just 48) put an end to Python, pretty much, though they’d not really worked together since their last movie, The Meaning of Life, in 1983. The remaining members got back together for their sell-out show at the O2 in 2014, and Spamalot (Idle’s musical of Monty Python & The Holy Grail) was a big hit on both sides of the Atlantic. However it’s for the TV shows, Holy Grail and Life of Brian that they’ll be remembered. The latter remains their masterpiece – heretical but not blasphemous, as Terry Jones put it (quite rightly). “It was, cleverly, not about offending anybody who had deep religious beliefs,” says Innes. ‘”It pointed clearly at the absurdity of how people follow things.”

Looking back, it‘s incredible to think that only 10 years separated their first TV show from their crowning glory, The Life of Brian. They’ve achieved a great deal on their own (Gilliam’s movies, Palin’s travelogues, Jones & Palin’s Ripping Yarns, Eric Idle’s Rutles, Cleese’s Fawlty Towers...) but in another 50 years it’s as an ensemble that they’ll be remembered, and people will still be using the word Pythonesque to describe something that’s both ridiculous and erudite, both extremely clever and extremely silly. Would Dibleyesque sound quite the same? Somehow, I don’t think so.

Monty Python at 50 is at BFI Southbank until 1 October. For more information visit www.bfi.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments