The story of Molière, one of the greatest comic geniuses the world has ever known

Molière’s art, his understanding of theatre and theatrical composition, was practical. Instead of spending 15 years writing, he toured the countryside speaking the lines, thinking the thoughts and feeling the passions of the characters others wrote, writes Kevin Childs

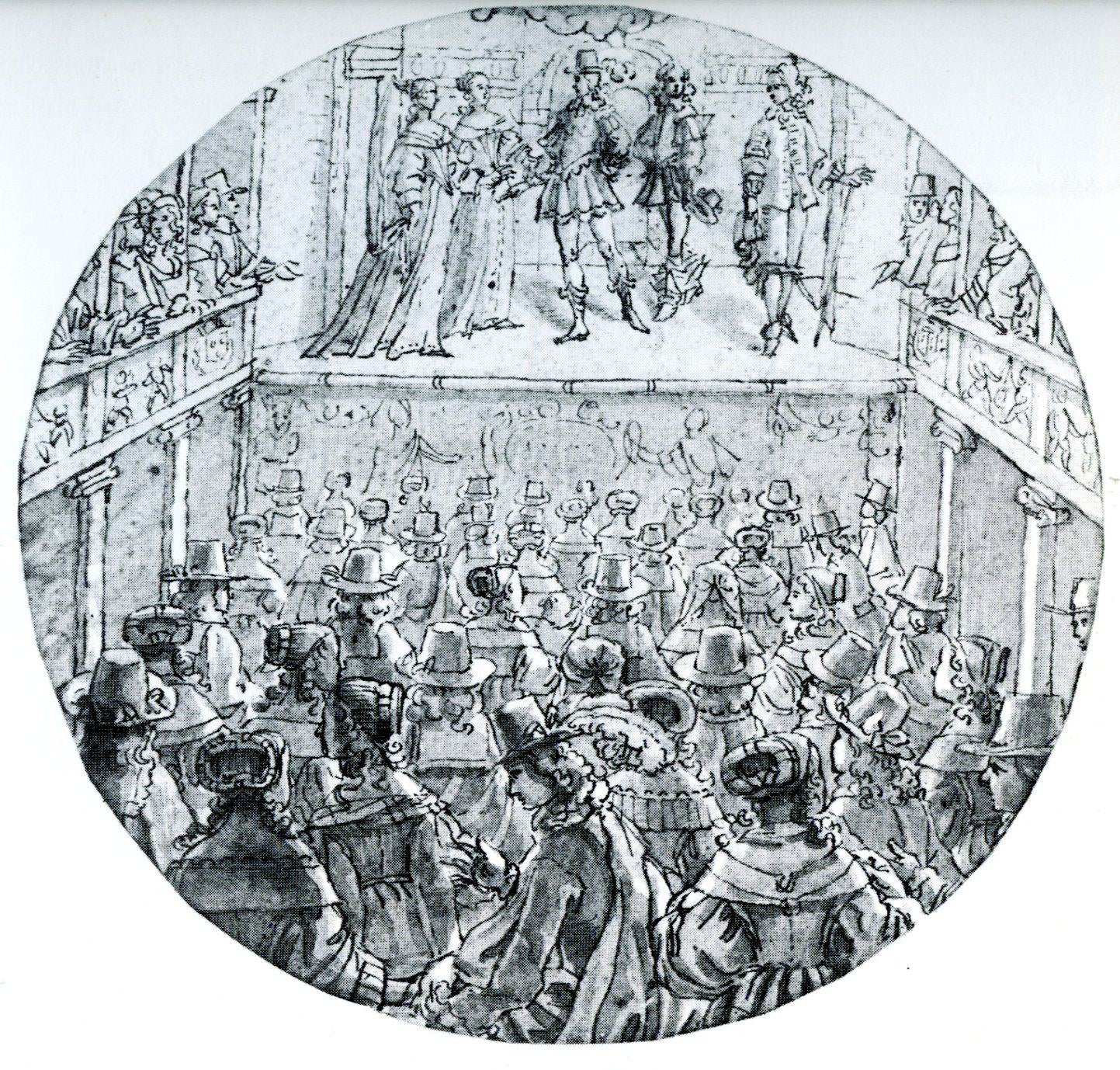

It was a first night like no other. The Salle des Gardes of the Palais du Louvre – now known as the Salle des Caryatides after the four female figures who hold up a musicians’ gallery over the main entrance – this great space, already more than 100 years old, in a palace much older and soon to be transformed, was glittering brightly with hundreds of candles in chandeliers and wall brackets. The light glinted on fresh gilding and even fresher paint, which decorated a newly built stage and proscenium, writhing with smiling nymphs and randy shepherds. A makeshift theatre in a grand room, like so many such spaces in France in 1658. The light shone and shivered on the diamond buttons and necklaces of the cavaliers and ladies.

For the 36-year-old actor, entrepreneur, theatre director and budding playwright, this was make or break. He and his troupe of players had spent 13 years touring country inns, draughty châteaux and hôtels de ville, mainly in the south of France, engaging people with cheap magic, rouged cheeks, affecting and affectionate leading ladies – not always welcome, sometimes chased unceremoniously out of town, but gaining an enviable reputation nevertheless. Tragedies and farces were their stock in trade, and as they gained in reputation and the money flowed in, the costumes for the former became more sumptuous while the humour of the latter grew more riotous.

Now they were coming home. Patronage, that shibboleth of the 17th-century stage, was at stake that evening. Philippe of Orléans, the 18-year-old brother of the king, known to the court and country as “Monsieur”, had agreed to extend his protection to the troupe without having heard them so much as recite a poem. Their reputation was enough. Tensions ran high on the temporary stage. The players of Paris’s most famous company, based at the Hôtel de Bourgogne, were clearly visible in some of the hastily constructed wooden seating. They’d be casting a critical eye over the proceedings, looking for fault, dying to damn these provincial nobodies as loudly as they could to their enthusiasts among the nobility.

What excited the troupe the most wasn’t the prospect of rivals, or Monsieur seated at the front of the audience on a gilded chair, or his mother, the Dowager Queen Anne of Austria, who rather disapproved of plays and players these days, but the presence of his brother, King Louis XIV, seated next to him. This they hadn’t expected. The 20-year-old Louis was known to be a connoisseur of good things and a difficult young man to please.

The play was an old hit for the Bourgogne troupe, by the most celebrated of France’s playwrights, Pierre Corneille. The choice of Nicomède was something of a folie de coeur for these players – to tempt this audience with this play on its home ground. The beginning was not at all auspicious. Their style of acting, promoted by the provincial troupe’s leader, was a long way away from the sonorous, trembling delivery of those stately alexandrine verses by a Montfleury or a Beauchâteau, leading lights of the rival company.

The new actors believed the lines should have a truth, a suppleness to them; that they should be something akin to ordinary speech. The result: only polite applause. The actors of the Bourgogne smirked, as the king and his brother rose silently to leave, the latter’s face as dark as a storm. But then the leader of the troupe appeared before them from behind the curtain, no longer in character, and with a mix of charming self-deprecation and breathtaking daring asked His Majesty if he would stay for a short farce – a one-act play that, he hoped, would amuse as much as Nicomède had clearly bored him.

The king nodded, the white plumes of his hat catching the candlelight. Quick costume-changes, a shift in mood, and the man who had delivered the lines of Corneille so elegantly and simply now began to race about the stage, grimacing and quipping quick-fire dialogue with his fellow actors in a piece about a doctor, hopelessly in love and thwarted at every turn. It was his own writing, light, slight – it had pleased the provinces, he told the king – but rip-roariously funny, peppered with bawdy innuendo and sexy wordplay. The Salle des Caryatides shook with laughter. The Queen Mother’s normally dour face broke into a smile. Even the guards couldn’t help themselves. And within a few minutes the king was slumped on his gilded chair wiping away tears, while his brother, who’d spent much of the evening in a state of mortification, shook merrily.

The actor-manager of the provincial troupe and his fellow players had triumphed at last. Molière was home.

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin was born sometime in January 1622. His father, Jean, was a prosperous tapissier, or cloth merchant, who specialised in beds and bedding and all things in between. He would inherit from his brother the title and rights of tapissier ordinaire du roi, which, while granting him the honour of supplying the royal household with bedding, also gave him the privilege – if it could be called a privilege – of making up the bottom of the royal bed after the King had slept in it: a duty he shared with four other valets du chambre.

Jean had married Marie Cressé the previous February, and Jean-Baptiste was their first child. Marie was from another long line of cloth merchants, specialising in linen and lingerie: not to be confused with anything from Agent Provocateur, these were napkins and bedlinen primarily. No one really wore underwear in those days. So young Jean-Baptiste grew up in a home full of fine beds, tapestries and nightshirts. The house, in which he was born and would spend much of his childhood, stood on the edge of the market district, Les Halles. It was known as the Pavillon des Singes, or the Monkey House, for the painted carved primates who cavorted down one side of its street façade handing oranges to one another. For the future great comedian who would so often be accused of “aping his betters”, it was appropriate, perhaps.

We can assume the young Poquelin had a happy boyhood here. Up until the age of 10, when his mother suddenly died – possibly in childbirth, possibly of tuberculosis – we know virtually nothing about him. What effect his mother’s death had on the boy is impossible to say. We don’t know how close Marie was to her first-born. In his plays, mothers rarely display unalloyed maternal love. Madame Pernelle in Tartuffe and Philaminte in the Les Femmes Savantes (Learned Women) always put their own ideas and pleasures before those of their children. Perhaps we shouldn’t try to sniff out biography in a writer’s works, but the consistent image of mothers as foolish and selfish is peculiar, as Philaminte makes plain:

My honour is at stake, and I won’t be denied.

Yes, you’re my flesh and blood, but you won’t shame my pride...

You see, in your best interests I’ve devised a plan.

You will be married here and now, and to a learned man;

My preference is Monsieur! And you will yet rejoice,

However you may feel, for I have made my choice.

Whatever he thought of his own profession, which had brought him wealth and social standing among the merchant class of Paris, Jean Poquelin had higher things on his mind for his eldest son. Jean-Baptiste was enrolled in the College de Clermont, probably around the age of 13. One of Paris’s most prestigious schools, Clermont was run by Jesuits. Its curriculum comprised Greek and Latin classics, ancient history and philosophy, with, of course, theology. The boys who attended were a strangely ecumenical bunch: a mixture of sons of the bourgeoisie, like Jean-Baptiste, and scions of aristocratic families, like the Prince de Conti. In the classroom, a hierarchy of talent prevailed. Social distinctions were irrelevant. For all we know, Jean-Baptiste was a conscientious scholar who made good use of his fine education and won many prizes. Or he was not. His school record hasn’t survived.

What we are told is that, as a child, he’d be taken to theatrical shows by his mother’s father at the newly built Hôtel de Bourgogne. Grandfather Cressé adored plays, and a lot of that enthusiasm would rub off on the young would-be player. No doubt he took part in the plays that were performed as part of Prize Day at Clermont, too.

And on Saturdays and Sundays when he wasn’t boarding, or during the long holiday, he might head for the Pont Neuf and idle away the odd hour watching the Italian clowns and mountebanks cavorting and selling snake-oil to the gullible in shows of predictable theatricality. Rumour has it that the young Poquelin joined one of these charlatans on his cart, acting as a credible plant among the gawping onlookers whose itinerant malady would be miraculously cured by some potion or other.

Whatever the truth of this, it’s generally agreed that, after leaving Clermont at around the age of 16 or 17, Jean-Baptiste Poquelin studied law, and may even have taken a degree at Orléans, then the principal school of civil law. As the process for taking a degree in law wasn’t particularly taxing and didn’t even require the prospective graduate’s presence in Orléans, it’s possible. But if Poquelin Sr had dreams of his son becoming an advocate or a minister of state, Jean-Baptiste had other ideas.

Among his school friends was Claude-Emmanuel Chapelle, whose free-thinking father had fostered a true sense of libertinism, a rejection of the bigoted swamp of societal norms, into his gay son. It’s not hard to imagine young Poquelin sitting among these hard-drinking epicureans, listening to their talk of experience as the true, the only mother of invention, and wishing his own staid family life were different. Mikhail Bulgakov suggested he might even have met the soldier poet Cyrano de Bergerac, who was beginning his career as a dramatist, here.

At some point in his late teens, the boy had been bitten sorely by the theatre bug, and nothing – not the law, not his father’s own industry and the prospect of becoming tapissier ordinaire du roi himself – would dissuade him. There was an interview. Jean-Baptiste told his father he intended to become an actor. Jean Poquelin no doubt mentioned his dead body. But in the end, the young man left without his father’s blessing, and a few hundred livres from the inheritance owed him from his mother’s dowry. The father wasn’t finished with his eldest son, however, and persuaded Jean-Baptiste to talk to an old friend. The serious, level-headed family accountant Georges Pinel would set him right. After the pair had spent a couple of hours huddled in a closed room, Pinel emerged with a smile on his face, telling Poquelin Sr that he was so thoroughly convinced that his son was on the right path, he was going to join him and become an actor himself.

Before then, however, Jean-Baptiste Poquelin had met and fallen in love with the beautiful red-headed tragedienne Madeleine Béjart, whose influence on him almost certainly prompted this change of career. Four years older than Jean-Baptiste, Madeleine was already a famous actress, most likely at the Théâtre du Marais, in the district of Paris where she and her family lived. The Marais, the only serious rival to the Bourgogne at the time, had given Pierre Corneille his first break, and had in its repertoire a number of good tragedies. Like so many aspects of this story, we don’t know if Béjart had an association with the Marais, but she would have had to learn her trade somewhere.

How and when Jean-Baptiste Poquelin met Madeleine Béjart remains a mystery too. They lived in different parts of Paris and inhabited different worlds – Madeleine was the mistress of the Comte de Modène – but somehow they found each other, and Poquelin found his childhood passion for the theatre reawakened. More than that, in 1643, with remarkable precocity, the tapissier’s son, just 21, decided that being a jobbing actor wasn’t enough. He wanted his own company, with Madeleine as the star and himself playing all those tragic princes and Roman worthies of the new French drama.

As so was born the Illustre Théâtre, its name perhaps the greatest temptation of fate in theatrical history. The young Poquelin – now styling himself the Sieur de Molière, a stage name by which he’d be known for ever more – along with members of the Béjart family – Madeleine, her brother Joseph, her sister Geneviève and her youngest brother Louis – formed the nucleus of the troupe, with others joining, coming and going, rising and falling as time passed. They begged and borrowed money to transform a tennis court on the left bank of the Seine into a theatre, with stage and boxes and pit. They bought costumes and props, and even managed to get the slippery, rivery, muddy area in front of the new theatre paved in stone so that carriages could deposit their fineries safely. Except those fineries didn’t come.

The Illustre Théâtre opened with a tragi-comedy by Nicolas Desfontaines, Alcidiane, justly consigned to oblivion by history (a ballet on the same subject with music by the great Jean-Baptiste Lully did rather better a few years later). The production failed, not least because the audience (such as it was) tittered at the actors, none of whom, with the exception of Madeleine, could deliver their lines well. An early biographer blamed the cast around Molière, who refused to follow him down the route of a more natural style of acting. But the reality is that the play was a stinker, and the performances bad. By the second night, no one, other than family members of the cast, came – the fate of many a fringe production.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Molière’s career during this period of exile was how long it took him to recognise his own talent for writing comedy

And the other problem was that the tennis court really was on the fringes – the wrong side of the river for the fashionable crowd; the young people who’d sunk every penny they owned – Molière had even borrowed from his father – simply weren’t a big enough draw. Nevertheless, the Illustre limped on for 18 months, changing venues and premiering a number of plays by new playwrights, until finally the bailiffs came, demanding creditors be paid. Poor Molière found himself in the debtor’s prison, and was only released when his father stumped up the money he owed.

The core of the troupe was undaunted. They took to the road, and 13 long years of touring the provinces followed, a sort of exile but one in which the actors honed their trade, attracted some established stars, and in which Molière himself gradually began to understand that his metier was comedy, not tragedy.

That’s not to say he wasn’t a good serious actor: two of the most impressive portraits painted of him in the 1650s show him in the roles of Caesar and Mars. But what he had to offer in that genre wasn’t what the public wanted, drugged up as they were on the bombast of the Hôtel de Bourgogne. Molière watched and was mesmerised by the Italian players of the Commedia dell’arte, hugely popular in the middle decades of the 17th century. Once his company was established in Paris, he would share a theatre with the principal Italian troupe.

These ribald and roaringly funny shows included stock characters – Pantaleone, Scaramouche, Harlequin and, later in the century, Pierrot – in typically bourgeois scenarios of thwarted old men whose love interests always go off with the right young men in the end. The plots were storied, the dialogue was improvised, the humour both physical (think Punch and Judy) and verbally witty. All this was delivered, inevitably, in a very natural, flowing style, much like normal speech, although a lot of what was said was improvised verse.

Molière recognised the value of the characters and stock narratives of the Commedia dell’arte, but he also found the naturalism of it all deliciously provocative. He would devise his own plays in much the same way, with dialogue, usually but not always written in verse, that flowed like banter between characters. The form he used – alexandrines or rhyming couplets in lines of six feet – had been wielded to good effect in tragedies by Corneille, and would be again by Jean Racine, but Molière understood its tremendous comic potential too.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Molière’s career during this period of exile was how long it took him to recognise his own talent for writing comedy. His reputation in the 1650s was as an actor and director of a successful touring group. He gained the patronage of a great personage, the Prince de Conti, who’d been a much younger pupil at the College de Clermont during Molière’s time there, but who would reject the company and anything to do with the theatre once the shady Compagnie du Saint-Sacrament – an ultra-religious society of bigots and bores who would cross swords with Molière several years later – had converted him.

A few short farces can be dated to the mid-1650s, including the piece which sent King Louis into paroxysms of laughter at the Louvre. But it wasn’t until he was nearing 40 that the greatest comic playwright in the French language wrote his first full-length comedy.

We don’t know why he waited so long to return to Paris. During the early part of the 1650s, France was shaken by civil unrest. A conflict known as the Fronde, between members of the nobility and the young king’s guardian and regent Cardinal Mazarin, soaked much of northern and central France in civil blood. The king’s capital was dangerous, not least for Louis himself, who had been forced to flee on more than one occasion. Mercenaries ranged across northern France.

It was only in the latter part of the decade, when the Frondeurs had been defeated – Cardinal Mazarin, the main bone of contention for the princes, had died, and a seemingly endless war with Spain was drawing to a conclusion – that peace was restored to France. A new order was coming, a new world premised on absolute power, and in that order the will of only one man mattered. All those men and women who’d opposed Louis a few years earlier, and who now vied with each other to flatter and be the perfect courtier in the perfect court, were ripe for satire. The Sun King would revel in it.

“Imagine, madame,” wrote Mlle Desjardins to her friend Madame de Morangis, “that his wig is so big it sweeps the floor every time he bows, and his hat so small it’s easy to judge that it won’t perch on his head. His cravat is the size of a dressing gown, his breeches seem to have been intended to conceal children in a game of hide-and-seek… his slippers are so covered with ribbons I can’t say what leather they’re made from… but I can say that his heels were half a foot high, and it was impossible to believe that such tall and delicate shoes could support his weight, his ribbons, his breeches and his powder.”

This description of Molière playing the fop Mascarille in Les Précieuses Ridicules, his first play written for a Paris audience, is a rare contemporary sight of the great comic actor at play on the stage. The one-act farce was performed in the great hall of the Petit-Bourbon, just across the road from the Louvre, which had been transformed into a theatre several decades earlier. The performers shared this space with the Italians and their spectacularly up-to-date stage machinery, all on the orders of King Louis, who’d been so impressed by his brother’s comedy troupe that he ordered the Petit-Bourbon to be made available to them on certain days of the week rent-free. It wasn’t until the latter end of 1659 and the beginning of 1660 that the Company of Monsieur had its first sure-fire hit in Paris.

Les Précieuses Ridicules, almost untranslatable into English, has in its sights the pretensions of those society ladies and gentlemen who thought the be-all and end-all was enshrined in witticisms, foppery, and the long-winded novels of Mademoiselle de Scudéry. Molière is careful not to actually represent the précieuses on stage, but the silly provincial bourgeoises, who are so blinded by their preciousness they’re easily taken in by a gentleman’s valet with pretensions to being a marquis, fooled no one.

In the first century CE, the Roman author Petronius didn’t dare present his master Nero in person in his novel Satyricon, but instead did so in the guise of the vulgar millionaire freedman Trimalchio. It’s an age-old trick of satire, and Molière would learn to use it to devastating effect. In all his great plays, from The School for Wives to Tartuffe to The Miser, it’s the bourgeoisie of Paris whose foibles are used to show up the behaviour of the courtiers of Versailles and the Louvre. The distortions in the mirror never entirely mask the original.

Gilles Ménage, a historian and a stickler for correct French usage, is supposed to have said to his friend M Chapelain on leaving the Petit-Bourbon one evening in 1660: “We have approved, you and I, all the nonsense that has just been criticised so ingeniously and with such good sense.” Notwithstanding Ménage’s liking of the play, the women of the salons were up in arms. Libels attacking the work’s author and the whole theatre scene flew about. Not for the last time, Molière found himself at the centre of a literary storm, and he seemed to revel in it.

He followed up his triumph with the School for Husbands and the School of Wives, not a sequel but an entirely different play, in which a supposedly wise older man grooms an uneducated young woman from the country to be the perfect wife, only to learn that a lack of education doesn’t mean stupidity. The play would influence contemporaries in England, in particular William Wycherley when he came to write The Country Wife. But what lifts The School for Wives from a merely farcical situation is the psychological insight Molière offers into his characters. Arnolphe, the old cynic whose constant foiling of the young lovers’ attempts to elope only make them more determined, about two thirds of the way through the plot, suddenly realises that he loves his young ward Agnes and is genuinely pained by her rejection:

And all the boiling ardour igniting in my heart,

Seemed only to increase that passion on my part.

I felt embittered, angry and somehow sorrowful,

And still I’d never seen her look so beautiful.

Her eyes had never pierced my own eyes. I’m done for.

I’ve never felt so much desire for her before.

I feel it here inside – I’m going to be destroyed,

Whatever fate’s unravelled, I cannot avoid.

Such a confession, so passionate an avowal, could never have come from the improvisations of the Commedia dell’arte. It’s the experience of a 40-year-old man who’s fallen in love with a much younger woman – a woman he’s seen grow up and blossom – and whose passion for her has crept up on him as though he were a frog in a pan of simmering water.

Molière parted company with Madeleine after 18 years or so – they never married, and he’d never been a particularly faithful lover – and fell in love with her much younger sister, Armande, who in all probability was Madeleine Béjart’s daughter by the Comte de Modène. In February 1662, Molière married Armande at the church of Saint Germain-l’Auxerrois, not far from the theatre in the Palais-Royal to which the Troupe de Monsieur had been forced to move when the Petit-Bourbon was demolished in late 1660.

It wouldn’t be a happy marriage. Armande de Molière liked the attentions of the beau-monde of the court too much; she liked finery and silk brocade and jewels; she liked the fact that the king stood godfather to her first child. The playwright-actor buried himself in work over the next 10 years. But the mismatch would inspire some of Molière’s finest plays.

In a moment of sweet fantasy, the great French fabulist Jean de La Fontaine imagined a scene in which four friends – himself, the satirist Nicholas Boileau, Molière and his fellow playwright Jean Racine – all visited the newly planted gardens of Versailles one summer’s day. Louis XIV’s gigantic palace, which was, in reality, a city, was under construction in the middle years of the 1660s when this expedition was supposed to have taken place. La Fontaine wants to read them his new work, a retelling of the old story of Psyche, the beautiful mortal princess beloved of the god Cupid, who suffers terribly at the hands of Cupid’s jealous mother, Venus. At one point, La Fontaine breaks off his reading, saying that the subject is too sad for him, and a debate begins between the four on the relative merits of tragedy and comedy.

Racine, who, a little after these events were supposed to have taken place, would betray Molière by switching camps from the Palais Royal to the Hôtel de Bourgogne in a particularly egregious way, contends that tragedy is the noblest art form. Molière, of course, comes to the defence of comedy, saying: “I’d much rather be made to laugh when I should weep than weep when I should laugh.”

Whether or not he ever did say that isn’t the point. He goes on to champion his metier, not as a mirror to bad behaviour – the traditional defence – but because “to laugh is divine. The gods never weep. Their state is one of laughter.” This epicurean defence is subtle. The gods are not laughing at us, they just don’t share in our travails, whereas the humour in Molière’s plays is always at someone’s expense. Comedy, in reality, is just one quip away from tragedy.

Antonin Robinet, one of the most important critics at the time, had christened Molière the “God of Laughter”. It was what had attracted the young King Louis to him, so that he soon took over the patronage of the Palais Royal troupe from his brother. It was why he wanted Molière to pen the entertainments he offered so lavishly in his new gardens at Versailles and other palaces around the Île de France – the most successful of which would take as its subject the story of Psyche.

It’s why he laughed so wickedly at the lampooning of his own courtiers in Le Misanthrope and Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme. Molière gave him pleasure, indefatigably, uncompromisingly, never complaining when the troupe was summoned to some distant château at a moment’s notice and required to play something new for the king and the Spanish ambassador, or for whatever other occasion demanded entertainment. They were always well paid – unlike his contemporary monarch Charles II of England, Louis could afford to be generous – but the schedule was gruelling, and the work at the Paris theatre suffered in their absence.

So it’s no surprise that when a real scandal struck the playwright squarely between the eyes, he felt hurt by the king’s lack of support. The School for Wives had generated much heat and very little light among the literati of Paris. It was a minor, unimportant scandal that only boosted the Palais Royal’s box office. But in 1664, the troupe presented to His Majesty three acts of a comedy that would become Tartuffe. The king laughed as heartily as ever, yet it wasn’t long before it became known that Molière’s new play was about a pious hypocrite who feigns religiosity to dupe a wealthy man of his money.

So what? You fail to make a true distinction

Between hypocrisy and real devotion?

You want to give the one the other’s rightful place

And render equal honour to the mask as to the face?

And mix up artifice with true sincerity,

Confounding the appearance with reality,

Respecting phantoms more than what your eyes can see,

And dodgy coinage over legal currency!

This was too much for the hierarchy of the Catholic Church in France. The secretive Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement mobilised its forces. No less a worthy than the Archbishop of Paris, Paul Philippe Hardouin de Péréfixe, reminded the king “that his extreme delicacy to religious matters cannot suffer this resemblance of vice to virtue, which could be mistaken for each other”. Louis was persuaded to ban the play “in order not to allow it to be abused by others, less capable of making a just discernment of it”. Molière ignored the king’s suggestion that he find some more suitable subject for his genius, and finished his comedy, but for the next five years he would plead, cajole, sulk and wear himself out on Tartuffe’s behalf, risking Louis’s displeasure and his own career at court.

Péréfixe threatened to excommunicate anyone who had anything to do with Tartuffe. This didn’t stop Molière and his company from performing it privately outside Paris, including for the king’s brother Philippe. Eventually the odium wore off, and the religious bigots slipped back to their self-mortifying justifications, so that in 1669 the ban was lifted. Molière had given Louis the role of unmasking the fraud Tartuffe, although he doesn’t actually appear on stage, and this may have gone some way towards persuading a man who was increasingly open to flattery. Molière’s friend Boileau would criticise this ending, thinking it a little too close to the sort of deus-ex-machina solutions of some tragedies. But despite its genuinely comic scenes and the razor-sharp satire, Tartuffe is very nearly a tragedy.

Each day I loaded him with all at my command,

I gave him everything, even my daughter’s hand.

And all the while this lying, treacherous jack-knife

Got it into his head to captivate my wife!

But not entirely satisfied with the attempt

The coward dares to threaten me with his contempt,

And plans to use the means I foolishly supplied

To ruin me with what I always meant to hide.

The run at the Palais Royal was a major success for the company, almost worth the years of frustration and waiting. But the controversy had taken its toll on more than the playwright’s relationship with his principal patron. Molière in his late forties was tired and increasingly ill. His marriage was on the rocks – he and Armande wouldn’t separate, yet they lived separate lives – and he was losing friends.

Tartuffe wasn’t the only play of Molière’s to fall foul of the censor. Dom Juan, his version of the Spanish legend about a libertine aristocrat, was also banned when it was first produced in 1665. The work, which is really a series of vignettes, sets up the libertine as a sort of admirable anti-hero, only to permit him to be damned in the final scene when the stone guest, a monument to one of Juan’s victims, drags him down to hell. Juan extols the virtues of hypocrisy in a speech all the more shocking for Molière’s contemporaries in that it’s placed, not in the mouth of a bourgeois or lowly chancer, but in that of a high-born aristocrat.

This is an art in which the imposter is always respected; and even when he’s found out, no one dares say anything against him. All the other vices of men are exposed to censure, and anyone is free to attack them; but hypocrisy is a privileged vice that holds its hand over the mouths of everyone and enjoys sovereign impunity.

It could be a commentary on the here and now. One scene proved too much to stomach and was cut from later productions and publications of the play. Dom Juan encounters a beggar and offers him a gold coin if he’ll blaspheme. When the beggar refuses, Juan gives him the coin anyway – not for the love of God, but for the love of humanity.

The following year, Molière produced what is often considered his greatest and most enduring play. While it has many comic scenes and fizzes with comic repartee, Le Misanthrope is hardly a comedy. The action revolves around the on-off relationship between the darkly philosophical Alceste – the misanthrope of the title, played originally by Molière himself – and the beautiful, impenetrable, coquettish Célimène, played by his wife Armande. Never was a pair of mis-matched lovers presented on the stage to such effect. Never was a stage relationship so redolent of the lives of the principal actors – at least, not until Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton played The Taming of the Shrew, perhaps.

Célimène seems to take delight in tormenting her lover with a host of idiotic suitors, while Alceste is obsessed with forcing her to prove her love for him.

Her faults are all mine; far be it from me to hide

One foible, and in doing so I’m on her side.

The more you love someone, the less your ought to flatter,

The purer the love, the graver the faults that matter.

And I would banish forthwith all these craven lovers

Who bow and scrape and vie to slip between the covers

And warm the feet of my complaisant abstinence

Or burn the incense to my wild extravagance.

Their sensible friends, Philinte and Eliante, despair of the couple and eventually, in trying to force Célimène to follow him into a sort of countrified exile away from Paris and the court, Alceste finally and predictably loses her. Molière develops his characters in a way that is quite alien to 17th-century French drama, in much of which characters are set, and what happens to them is dictated by fate. Alceste is, perhaps, the first modern man, disgusted by the wastefulness of society and the perfidiousness of his fellow men, and determined to live his life according to his own rules.

Enough! I want no more of misery by rote:

Let’s ditch this cup and slip the knife that’s at my throat.

I’ll take my chances with the fire, not the pan,

Since man is just a vicious wolf that preys on man.

Conversely, Célimène is her own woman, and won’t be coerced into a conventional role by Alceste or the disapproval of society, represented by the grandly hypocritical Arsinoé. As she tells Alceste:

And just because we struggle with our acumen

When we resolve to open up our hearts to men,

Because the honour of our sex, love’s enemy,

Fights tooth and nail to stop our mouths, you must agree

The lover who will cross this chancy avenue,

Should not be doubted when she says that she loves you.

And isn’t he as guilty when he makes denial

Of what is never said without a great trial?

That Molière felt he had so much to say about the pale seductions of modern life – and he doesn’t try to hide his critique under a veil of bourgeois innuendo – indicates how far he had come as a playwright and as a disassociated, even cynical, mover in the world of courts, theatres, literary salons, the Académie Française and political chicanery.

That he’d also made enemies along the way, like Alceste in his play, was inevitable. The actors of the Hôtel de Bourgogne despised his success. The precieuses of Paris were enraged by his lampooning of them. The doctors, on whom he’d increasingly rely, may have looked askance at being another butt of his humour. When he made fun of the literary pretentions of a certain character in one of his plays, the Duc de La Feuillade, thinking he was the target of the satire, took revenge on the playwright in a particularly exquisite, indeed precious, way. Encountering him at court one day, the duc made to embrace Molière, but instead crushed his face against his embroidered coat, the buttons of which were diamonds. It was a brutal encounter, which left Molière humiliated and with blood dripping from his nose.

But the actor was growing tired of the play. Increasingly unwell, Molière spent more and more time in a little apartment he’d rented in Auteuil, by the Bois de Boulogne, about a two-hour ride from the centre of Paris. Here he would write, entertain friends, and confine himself to the strict milk diet his doctor had recommended to combat the increasing influence of what would turn out to be tuberculosis.

One anecdote of his time at Auteuil involves Molière’s old friend from school, Claude-Emmanuel Chapelle, by then a minor writer who was busy drinking his talent into oblivion and seeking out the comfort of like-minded men from among the demi-court of Monsieur, Philippe of Orléans. It goes like this:

Chapelle has invited friends to join him at Auteuil, including the famous composer Jean-Baptiste Lully. Molière has the beautiful young actor Michel Baron, a recent addition to the troupe, with him, and both Chapelle and Lully jockey for the boy’s attention. As the company are drinking heavily, Molière has gone to bed, although the others insist Baron stays with them. At about three o’clock, Chapelle starts to lament the course of his life:

For 30 or 40 years we are on the look out for a moment of pleasure, a moment we can never find. Our youth is spent appeasing our parents’ ridiculous hopes for us, stuffing our heads with nonsense they call education. Love is nowhere to be found. Sorrow, injustice, unhappiness dog us in this life!

The others agree, and one suggests they all commit suicide. “Let’s go drown ourselves. The river is at our door.”

They rush out of the house and stumble across the muddy ground to a small wooden landing stage by the Seine. Baron, meanwhile, who wants no part of this escapade but is worried the friends might do something foolish, goes to wake up Molière. At the riverbank, the friends fight with a group of locals who are trying to stop them from wading in. Finally, Molière arrives, and, while he agrees that the world is a terrible place, and they should all commit suicide – “You want to drown yourselves without me? I thought you were my friends!” – he suggests that now is not the time. Between eight and nine in the morning would be better, he suggests. Sober and rested, no one could accuse them of drowning themselves by mistake.

After a few hours’ sleep, the company get up and shamefacedly return to Paris.

The extent to which actors were truly despised at the time is shown by the aftermath of Molière’s death. The local parish priest refused to bury him because he had not renounced his ‘sinful’ life

We don’t know if the story is true. It’s fallen into myth, but it’s worth considering as a sort of palimpsest of truth. Life was never easy for Chapelle, it seems, despite his private income. He longed for the approbation of the great artists he knew, and for the love of a handsome young man. His mood infects the others, and the wine does the rest. Molière, feeling old and sick and harassed, nevertheless puts a comic gloss on the proceedings, and persuades his friends towards the more sober course of putting up with life’s vicissitudes rather than ending them messily. It could be a scene from one of his plays.

Except it isn’t. Molière was, in fact, gravely ill, and only two years or so from his death. By 1670 he had reconciled with Armande, and they were living together once more. She had also agreed to accept the young Baron into the company of the Palais Royal and into her house as her husband’s protégé, though she was insanely jealous of the proto-familial relationship between them. Perhaps Armande had felt a little more like Molière’s daughter in the old days – libels had actually suggested she was his child – and she couldn’t reconcile herself either to the new role of wife or to the interloper boy actor her husband treated like a son.

An uneasy peace had settled on their household, which, in the autumn of 1672, moved to the Rue de Richelieu. After the long disappointments of Tartuffe and its eventual success, Molière was writing again. He was collaborating with Lully on court spectaculars – Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme and Psyché in 1670 and 1671 respectively – and he still had two major new plays that he would write in 1672: Les Femmes Savantes, a more sophisticated riff on the subject of supercilious bluestockings than Les Precieuses Ridicules, and Le Malade Imaginnaire, which would shudder onto the stage in such a strange echo of Molière’s life and presage of its end.

In February 1672, Madeleine Béjart died. Her relationship with Molière had been long, at times passionate, often cool, but there had never been a break. What she thought of her lover and collaborator marrying the girl she claimed was her sister, but who was in all probability her own daughter, we do not know. She continued working with the company, shifting from tragic heroines to wily lady’s maids, as the troupe’s repertoire changed. In the end, she wrote to formally renounce her profession, a necessary act in a time when priests often refused to bury anyone associated with the stage. It’s worth being reminded that the Catholic Church has its puritans, too, and that they considered actors to be whores and sodomites, in the language of the time.

A year to the day of Béjart’s death, Molière was on stage acting the role of Argan the hypochondriac in Le Malade Imaginaire. In the last act, Argan pretends to be dead in order to test the love of his family. The actor had been troubled by a bad cough for some time, and it was particularly acute during the performance, his breathing noticeably difficult, even if it added a touch of realism to the scenario. He barely made it though the last act, and was taken immediately back to his house on Rue Richelieu in a sedan chair, Michel Baron muffling him up in furs because he complained of feeling deathly cold. Once in bed he was overcome with a fit of coughing, and nearly filled a basin with blood. Baron ran to fetch Armande and a doctor, but by the time they returned to the bedroom, Molière was dead.

It is said that France’s greatest actor had once tried to dissuade a young man from joining a stage company. It would ruin his life, he said, and he would lose family and friends if he tried. It’s an unlikely story, but there is a grain of truth in the description Molière supposedly gives of an actor’s life:

Imagine the troubles we have. Sick or not, we have to tread the boards nightly and give pleasure even when we are overwhelmed with grief; we must put up with the vulgarity of the majority of people we’re forced to live with and charm the public who assume the money they pay us gives them the right to abuse us.

The extent to which actors were truly despised at the time is shown by the aftermath of Molière’s death. The local parish priest refused to bury him because he had not renounced his sinful life. Armande had to petition the Archbishop of Paris, her husband’s old enemy, begging him to order the curé of their local church to conduct the funeral. She went to Versailles to see the king, and only then did the archbishop relent. Molière could be buried, but without ceremony – without even a proper service.

Whatever the archbishop ordered, the God of Laughter was followed by a great multitude carrying torches from his house to the cemetery of Saint-Joseph. We don’t know exactly where he was buried. A stone tomb was erected by his widow in the very centre of the place, but it’s believed his bones lie in another site on the margins of the cemetery. Someone was dug up in 1792, and the remains were designated Molière’s and kept in various locations, eventually finding a permanent spot in Père Lachaise, the Elysian Fields of the great and the good, next to his friend La Fontaine.

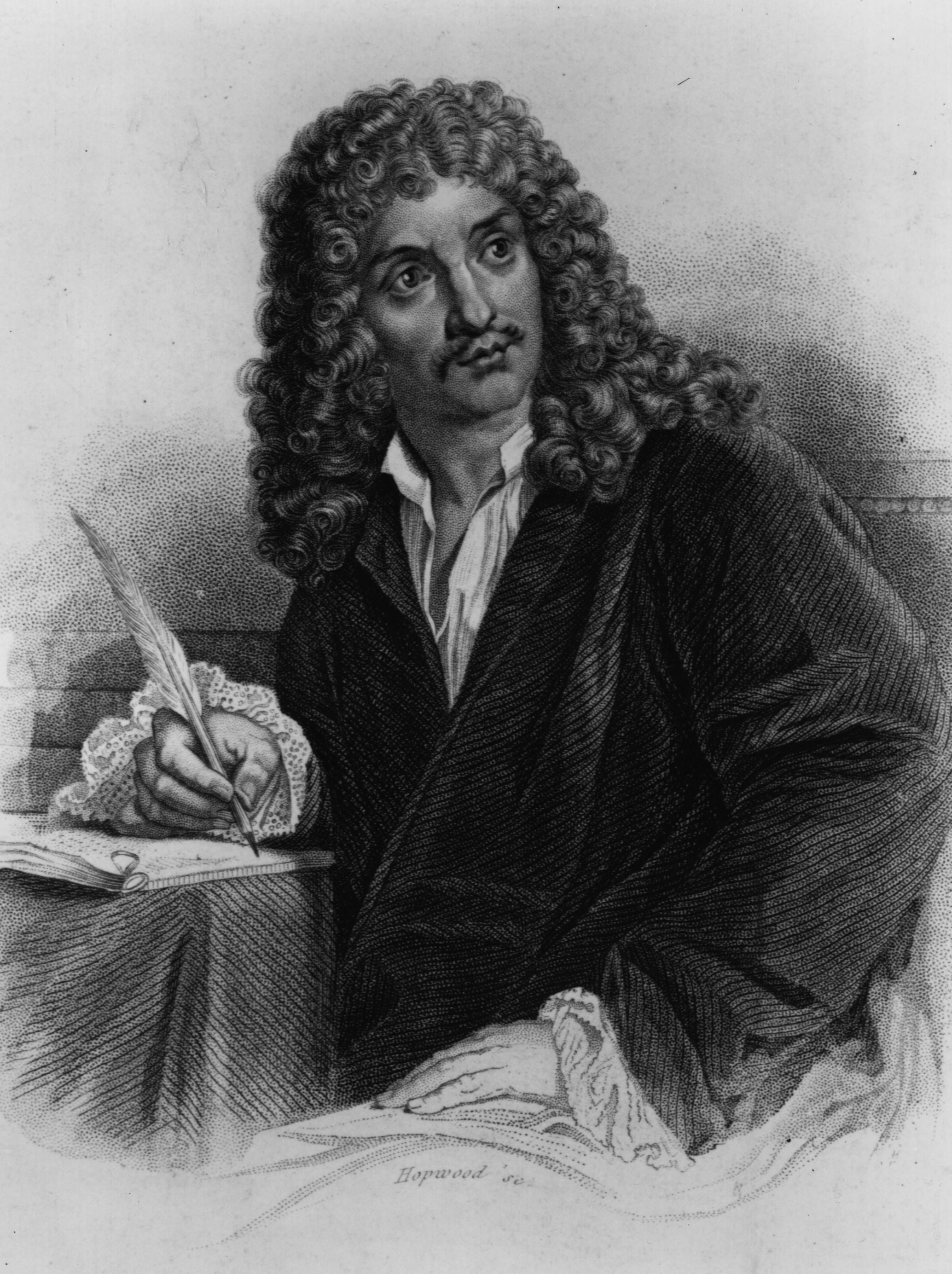

Many of the portraits painted of Molière later in his career, by Pierre Mignard for example, show the playwright with a lightly furrowed brow, wrapped nonchalantly in a silk dressing gown, a pen in his hand or contemplating a book. The image of the actor, the man of action we saw in early portraits, has been exchanged for that of a writer, contemplative and thoughtful. He could be any one of the writers of the Grand Siècle.

About 100 years ago, critics began to doubt that a mere actor could possibly have written the plays published under the name of Molière. They suffered from the same delusions some people have about Shakespeare – that unless you’re of a particular class and a particular education, you cannot possibly be a genius, and certainly not a literary one.

Yet unlike contemporary playwrights – Corneille, Racine, Cyrano de Bergerac – Molière’s art, his understanding of theatre and theatrical composition, was practical. He was trained as an actor, although he also had the kind of education at the Clermont that gave him the same intellectual tools as his rivals. But instead of spending 15 years writing good Horatian odes, Molière toured the countryside speaking the lines, thinking the thoughts and feeling the passions of the characters others wrote. When in time he came to write his own characters, they grew from the inside out: they were natural creations, who spoke as though they breathed, rather than talking statues. In a short play he wrote in defence of The School for Wives, Molière has one of his characters say just this:

[W]hen you portray real people, as in comedy, you have to draw from life. Your audience wants your portrait to be recognisable. Unless they can recognise their contemporaries, you’ve achieved nothing.

A painting by the rococo artist Jean François de Troy, painted in the 1720s, shows a group of wealthy bourgeois listening to one of their number reading from a play by Molière. It’s pretty, elegant, decorous, and entirely incongruous to the nature of Molière’s plays. These were exactly the people represented in his comedies, the people at the sharp end of his satire, and yet here they are smiling benignly at their own folly.

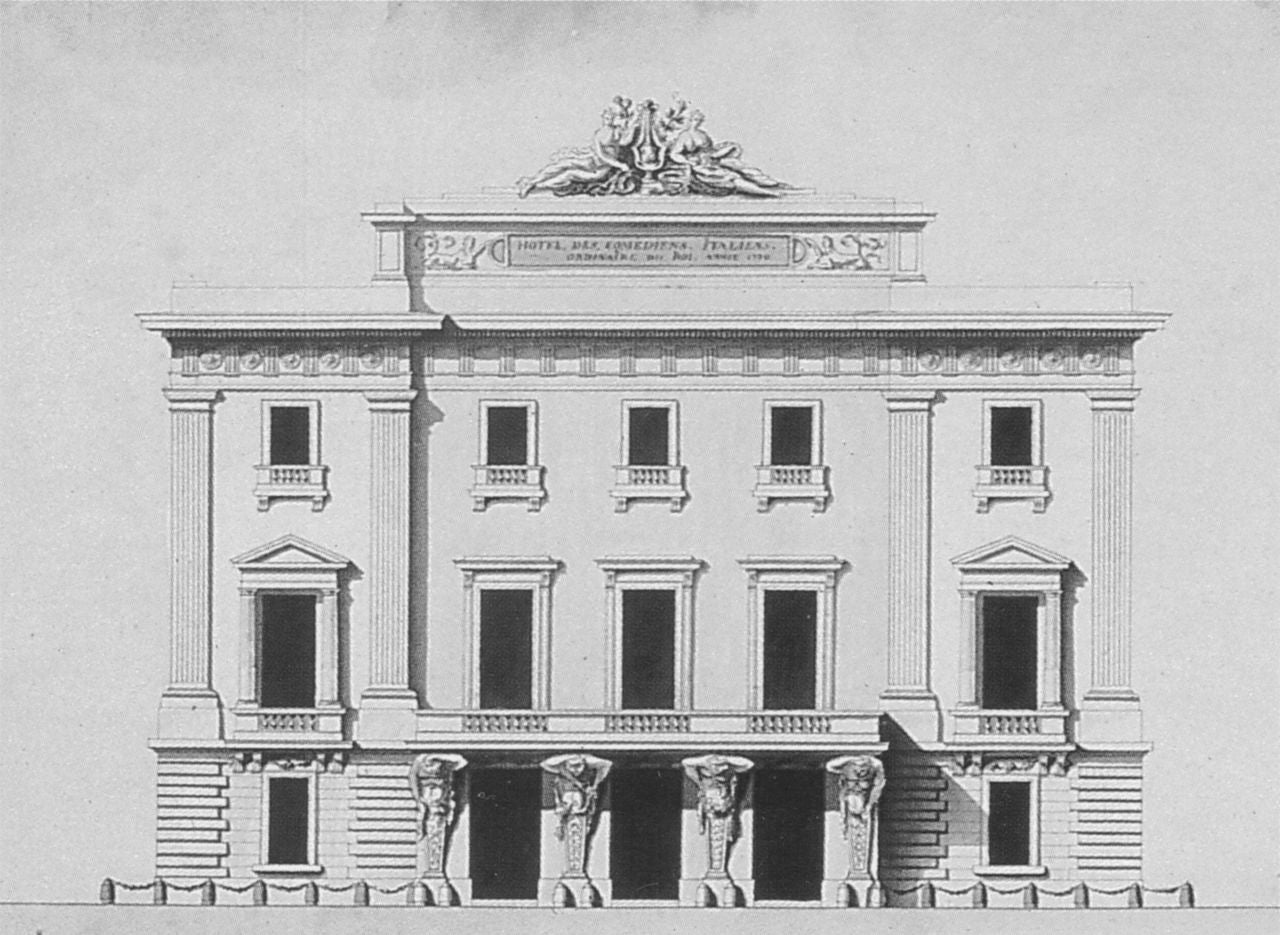

Seven years after his death, in 1680, the troupe Molière had founded, and that his wife and Baron had continued with, was merged by royal decree with the players of the Hôtel de Bourgogne. A new charter brought it into being, and a new company was formed. It still exists today. The Comédie-Française performs the plays of Molière and Racine, among others, although as its name suggests, if there were ever a war between tragedy and comedy in the Grand Siècle, the latter would clearly have won.

At some point in the decades after his death, Molière became a classic. He was literally deified, and the presentation of his plays became so set in its ways, so sacrosanct, it took several revolutions in France to recalibrate the audience’s relationship with him.

One of the actors who worked with him, Angélique du Croisy, left a pen portrait of the man. She wrote:

Molière was neither too fat nor too thin; he was more tall than short, he had a noble bearing and a handsome leg; he walked slowly, gravely, with a very serious air. His nose was large, as was his mouth; he had thick lips, a dark complexion, heavy black brows, the various movements of which made his expression very comical … Nature had refused him those external gifts so necessary to the stage, especially for tragic roles.

It was inevitable, it seems, that comedy – no matter how close it might come to tragedy at times – would be his forte. To cry is human, to laugh divine, after all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments