The ‘chilling’ case of Michael Hickson and disability rights in the wake of coronavirus

The case of a Texan quadriplegic who died after all life-sustaining treatment was withdrawn is all too familiar to disabled people on both sides of the ocean during the pandemic, writes Holly Baxter

Michael Hickson’s wife is softly spoken and calm when she addresses the doctor on the phone. “What do you mean?” she says. “Because he’s paralysed with a brain injury he doesn’t have a quality of life?”

“Correct,” says the unidentified doctor, who is speaking with her from St David’s Medical Centre in South Austin, Texas.

“Who gets to make that decision on somebody’s quality of life? If they have a disability, that their quality of life is not good?” Melissa presses him. “Being able to live isn’t improving the quality of life?”

“There’s no improvement with being intubated, with a bunch of lines and tubes in your body, and being on a ventilator for more than two weeks,” the doctor replies. “Each of our people here have Covid and they’re in respiratory failure. They’ve been here for more than two weeks.”

“So they’re basically on a ventilator ’til they die?” Melissa asks.

“If I were to be frank, yes,” the doctor says.

It’s a difficult phone call to listen to, and it gets more distressing as it continues. As the doctor at St David’s continues to explain to Melissa why his team are choosing to withdraw all life-sustaining treatment for her husband – including his feeding tube – she continues to insist that Michael might be able to fight off coronavirus if he’s given nutrition, hydration and medication for the next few weeks.

“Just so you know, my uncle got Covid. He’s 90 years old and he has a bunch of medical problems. He has cancer,” she says, and before she can add that her uncle survived Covid-19 and is now in recovery, the doctor – who the hospital has refused to identify – cuts in to say: “I would consider that a blessing every minute he’s still alive.” Melissa tells him that her husband is much younger than her uncle and might therefore have a good chance of survival. The doctor replies: “Well, I’m going to go with the data. I don’t go with stories because stories don’t help me. OK?”

Later in the call, Melissa says she understands intubation might be futile for her husband, but that she disagrees with the decision to remove everything. “That’s saying you’re not trying to save somebody’s life,” she says. “You’re just watching him go. The ship is sailing. I mean, that doesn’t make any sense to me to not try. I don’t get that part.”

Melissa asks the doctor if he would do the same for his own spouse. “I would totally do this if this was my mom, my dad, my brother, my sister, my spouse,” the doctor responds. “I have seen this certainly more than you have and I have seen people die.”

“You’ve seen it more but you haven’t felt it like this because it’s not personal,” Melissa suggests.

“You don’t know anything about me,” says the doctor.

“Well, and you don’t know anything about me,” says Melissa, clearly taken aback.

At that point in the call, Melissa’s friend jumps in to ask everyone to “relax” and the YouTube video featuring Melissa’s audio recording fades out to the end.

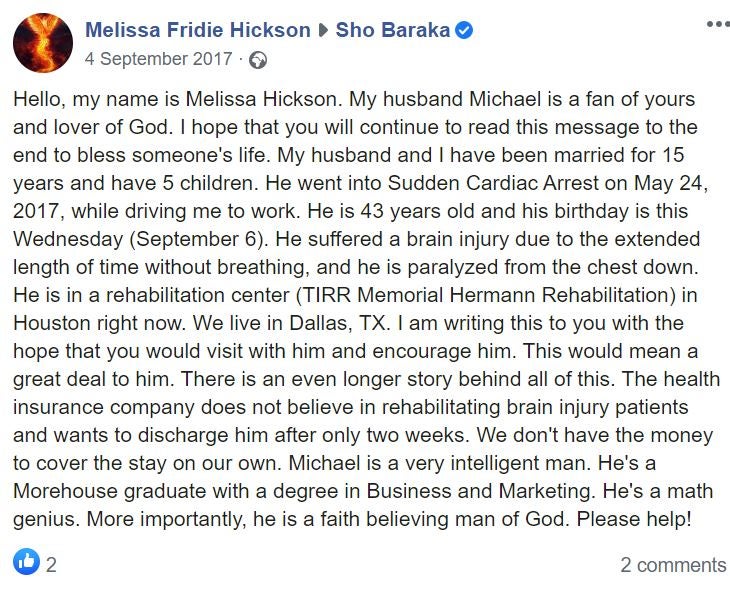

Michael Hickson was admitted to hospital with coronavirus on 2 June. He died just a few days later on 11 June, and the phone call appeared on YouTube on the 26th, after first being sent by Melissa to local news station KVUE. A 46-year-old father of five who was quadriplegic and lived with a brain injury, Michael had been disabled for three years. Facebook photos show him smiling with his arms around his wife, grinning in his chair, lying down surrounded by his children, and hugging a gigantic teddy bear in bed while laughing.

The coronavirus crisis has put back the cause of disability rights by decades, and that’s no exaggeration. The notion, on both sides of the Atlantic, that disabled lives have less value is deeply offensive and frankly disturbing. Like many people with disabilities, I felt a profound sense of fear in the early days of the crisis

“The reason we go to hospital is to be treated, and not to be based on a scale,” Melissa said in an interview with KVUE while standing outside her cream-painted house, a plain wreath hanging on the door in the background. “It’s merely to be saved… Basically his voice was taken away and put in the hands of an organisation that didn’t know anything about him, his history… they didn’t know anything about him.”

Michael’s legal guardian was an organisation called Family Eldercare, which was appointed because his wife and sister both battled for the right to be his advocate in court. It was a decision that was supposed to work for everyone, but after Michael’s death, seems to have worked for no one. The doctor from St David’s was ringing to inform Melissa of the decision made between Michael’s medical team and what he refers to as “the state” (in other words, his state-appointed guardian). Melissa had no part in the decision, despite protestations that “his wife, his family, his five kids” should be able to swing the judgment.

Numerous pro-life organisations in Texas have taken on Michael’s cause after his death. Though Melissa herself supplied the phone call recording to KVUE, its translation into a YouTube video complete with transcript was done by Texas Right to Life, a Christian organisation which mainly “fights for the rights of the unborn” – in other words, fights to lessen and challenge access to abortion. Such “pro-life” groups also occasionally dabble in disability advocacy cases like Michael’s.

Texas Right to Life claims that Michael was “starved and left without adequate treatment for his illnesses”, whereas Family Eldercare says that he was provided with “hospice care” that included nutrition, hydration and “comfort” medications (doctors have since said that in actuality, nutrition was not provided). Nobody disputes that the antiviral drug remdesivir was available to Covid-19 patients at the time Hickson was in hospital, but doctors chose not to give it to him because he didn’t “fit the criteria”. Michael’s doctor says at another point during his phone call with Melissa that the hospital has a policy stating that patients have to be intubated to receive remdesivir, and Michael wasn’t a good candidate for intubation. They were not willing to make an exception.

For a couple of weeks after his death, it seemed like Michael would simply be written up as another coronavirus statistic – filed under “pre-existing medical condition” – and forgotten about. But when pro-life groups began sharing Melissa’s interview, they caught the attention of disability groups and by 2 July the National Council on Disability, which is a US federal agency, had released a statement. We are “shocked and saddened by the unnecessary death of Michael Hickson”, wrote chairman Neil Romano. “Hickson’s death resulted from a hospital’s refusal to provide him with life-saving care for Covid-19 and withholding nutrition and hydration … The presence of a disability does not lessen a person’s value, nor should it warrant a person’s abandonment by the medical facilities they rely on for care. When a medical facility makes a decision to deny medical care to a person with a disability that is based on, or influenced by, biased views about life with a disability, it runs afoul of federal civil rights laws.”

After the statement, the hospital where Michael died subsequently obtained a legal release in order to discuss his case in more detail with the public. “I wouldn’t typically share this level of detail about a patient with the public, but I am troubled by the untruths being shared about Mr Hickson’s care and the circumstances of his passing,” said DeVry Anderson, the chief medical officer at St David’s. “Some people want the public to believe that we took the position that Mr Hickson’s life wasn’t worth being saved, and that is absolutely wrong. It wasn’t medically possible to save him.”

The reason we go to hospital is to be treated, and not to be based on a scale. It’s merely to be saved. Basically his voice was taken away and put in the hands of an organisation that didn’t know anything about him, his history

“Mr Hickson was very, very ill when he arrived at our hospital. He was transferred to us from another facility with pneumonia in both lungs, a urinary tract infection and sepsis. He also had Covid-19. Despite aggressive treatment and one-to-one care, Mr Hickson went into multi-system organ failure,” Anderson continued. “He had a number of complications. As one example, near the end of his life, he was aspirating – meaning that he was regurgitating the nutrients going into his body through his feeding tube, and they were going into his airways, causing his respiratory condition to worsen. Aspiration has the potential to be fatal, especially for a patient in a weakened physical state, like Mr Hickson, and this was the reason his tube feedings were discontinued.”

Anderson addressed Melissa’s claim that she had only been allowed to see her husband before his death when Family Eldercare said so, and even then only with security present. Those claims were true, he said, but at Melissa’s request, the hospital then had a dialogue with Family Eldercare that allowed Melissa to have more visitation rights and alone time with Michael. Anderson, who is black, also addressed accusations that the choice to withdraw all care from Michael was racially motivated and that the higher death rates of black people from Covid-19 proved doctors fought less hard to save them, especially when they are also disabled: “This was not a matter of hospital capacity. It had nothing to do with Mr Hickson’s abilities or the colour of his skin … This was a man who was very, very ill and in multi-organ system failure. His legal guardian and his doctors worked together, consulting pulmonary and critical care specialists, to determine a care plan that was best for him … Hospice care began, at the direction of the court-appointed guardian, when it was clinically indicated that the patient was not going to survive his illness. At that point, every effort was made to make the patient comfortable. Our team knew Michael Hickson, and we cared for him. His life was deeply valued, and we felt the loss of it.”

No doubt the doctors at St David’s did care for Michael, and that none of them took his death lightly. However, the flippant and sometimes dismissively cruel way in which his primary physician spoke with Melissa on the phone while communicating the decision to remove care leaves a bad taste in the mouth. For Melissa, it was deeply traumatic.

“Who gets to make that decision on somebody’s quality of life?” – the question Melissa asked on the phone – is important. At one point during the conversation, the doctor offhandedly says that the three severely ill patients he has who survived coronavirus were different because they were “walking and talking”, when Michael would clearly never have been able to walk because of his quadriplegia. Such remarks seem casually ableist, even if the doctor meant no harm. And rooting out those assumptions is particularly important during a pandemic, when patients are quickly triaged in a way that relies on doctors’ snap judgments. Early in the Covid-19 outbreak, one doctor at a British hospital told the BBC that she felt terrible guilt about the fact that one patient who was on a permanent ventilator arrived at hospital from a care home with coronavirus and “all I could see was the ventilator”. She was already planning for who they would reassign that ventilator to after the patient’s death when she saw them arriving, she admitted.

Doctors and nurses have to make extremely difficult choices on a daily basis that most of us will never have to make. They try their best to do right by their patients and to divert resources to those with the best chance of survival. However, in doing so, they will sometimes make the wrong call. And Covid-19, in particular, is a strange disease, one which kills off 17-year-old high schoolers and 25-year-old mothers for no discernible reason, while 95-year-olds in nursing facilities are discharged from hospital in full recovery and 71-year-old Prince Charles reports having symptoms so mild he barely noticed them after a couple of days. In that way, coronavirus has more in common with a disease like cancer than it does with the seasonal flu: some people will buck the odds for no reason at all, something in someone’s genetics might kick in to their advantage. Statistics are only helpful up to a point.

Treatments, too, can sometimes give surprising results, and reserving them only for the patients doctors presume are most likely to benefit is a dangerous strategy when you’re dealing with an illness that has existed in the human population for less than a year. Michael may not have “fit the criteria” drawn up during the Covid-19 pandemic for remdesivir, but was that a reason not to try it as a last resort on compassionate grounds? Taking such action is hardly uncommon – and there is no need for a patient to be intubated to receive remdesivir, considering it is given through a simple IV.

I ask Independent columnist James Moore, who has been active in the cause of disability rights, about his thoughts on the circumstances surrounding Hickson's death. He says: “Michael Hickson’s case is chilling, but not surprising. There have been reports of people in care having do-not-resuscitate orders signed without their permission by staff, [and others suggesting that] having a mobility impairment would count against you if beds were in short supply.”

“The coronavirus crisis has put back the cause of disability rights by decades, and that’s no exaggeration,” Moore adds. “The notion, on both sides of the Atlantic, that disabled lives have less value is deeply offensive and frankly disturbing. Like many people with disabilities, I felt a profound sense of fear in the early days of the crisis. My wife was similarly worried about what might happen if I were to get it badly enough to be hospitalised, and with good reason. The messaging we were seeing said I’d be at the back of the queue for a ventilator. As it turned out, while I had a nasty case, I didn’t require hospitalisation.”

US disability advocacy charity ADAPT led a protest and a candlelight vigil for Michael this week, and their Facebook page features an image of one person holding up a placard which reads: “Doctors, nurses, will you be complicit in eugenics?” A somewhat morbidly named grassroots anti-euthanasia and disability rights group called Not Dead Yet supported the protest and published additional photographs of people in wheelchairs holding up signs that say “Disabled not disposable”, “Worthy of life” and “Justice for Michael Hickson”.

Moore is clear that now is the time for medical professionals to challenge preconceived ideas they might have about people with disabilities and what their quality of life entails: “Parts of the medical profession and public health authorities need to examine their consciences,” he tells me. “It wouldn’t hurt if they were to talk to us. They might then see us as what we are: human beings due the same rights as anyone else. Instead, there’s this notion of disabled people as somehow subhuman, and that comes from a very, very dark place. It needs to be addressed.“

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments