Metaverse: The world of tomorrow or a dystopia waiting to happen?

As Mark Zuckerberg announces his newly branded company is on a mission to create a 3D virtual reality for us to live in, Steve Boggan asks what it might look like and if it could be the end of the real world as we know it

When James Cameron’s groundbreaking movie Avatar was released in 2009, one cinemagoer who didn’t like it, famously joked that it had been made in 3D because Cameron couldn’t fit so much rubbish into two dimensions.

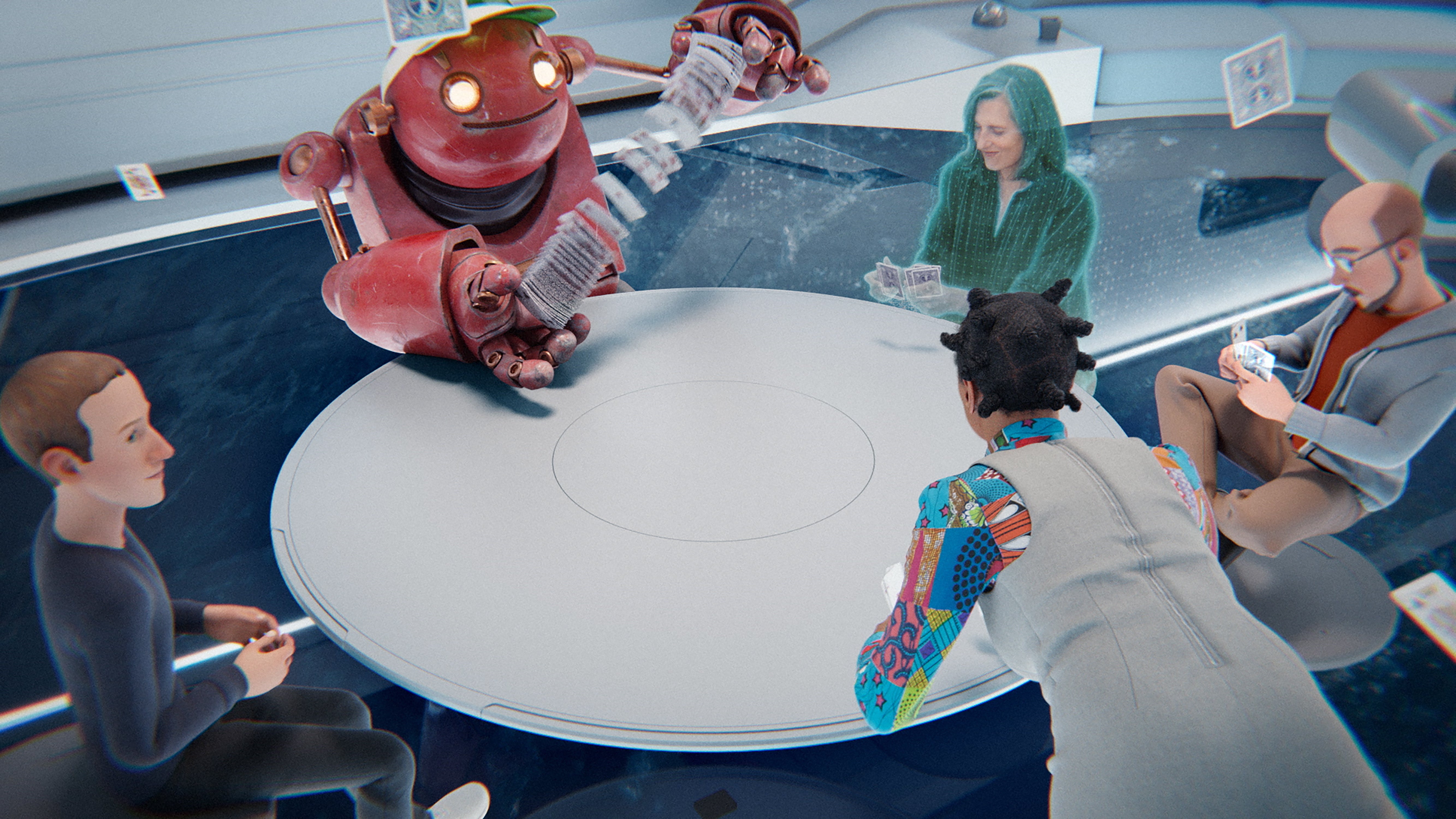

It was a cheap shot, especially given that most audiences enjoyed the film enormously, but the joke was given fresh legs recently when Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, grandly announced that his newly branded company, Meta, was on a mission to create the “Metaverse” – an immersive 3D upgrade to the internet in which digital representations of ourselves could work, play, learn, socialise and be creative.

Had Zuckerberg realised that he had exhausted the physical universe, overmilked users as advertising cash cows, undermined the body images of too many girls, debased democratic processes across the globe and given birth to countless binary hate bubbles for one universe to contain? And so, like Cameron’s dimensions, he needed another virtual one that would be occupied by our digital substitute selves – our avatars?

In the light of claims made by Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen that executives and employees of the company – which also owns Instagram and WhatsApp – put profit before users’ wellbeing, Zuckerberg’s insistence that he was the right man to oversee the evolution of the internet into the Metaverse was alarming – not least among tech and 3D specialists who had already spent years working to create it.

To them, his rebranded focus on the Metaverse was an unwelcome shock. They had envisioned multiple metaverses (and still do) but experience has shown that Facebook likes to control the space it occupies, gobbling up any company that poses a threat to its dominance. To most of the rest of us, the creation of Meta came as something of a Big Bang moment. The Metaverse, a word the majority of us had never spoken, was suddenly on everyone’s lips.

It would change our lives and give us virtual new ones. Wearing ubiquitous 3D virtual reality (VR) or augmented reality (AR) headsets, we would work in it, play in it, create in it and do business in it. Some of us would become fabulously wealthy in it. And, whisper it softly, we would be offered sexual gratification in it, become the victims of crime in it, fall in love in it… and, inevitably, some of us would go mad in it.

So, what is the Metaverse and what could it mean for the advancement of humankind?

First of all, it isn’t new; it is already here to some extent and it wasn’t invented by Mark Zuckerberg. The term was first coined by the American science fiction writer Neal Stephenson in his 1992 novel Snow Crash in which characters wear VR headsets in order to enter a digital world called The Street, where their avatars could travel, interact with other avatars, conduct business and buy and sell real estate.

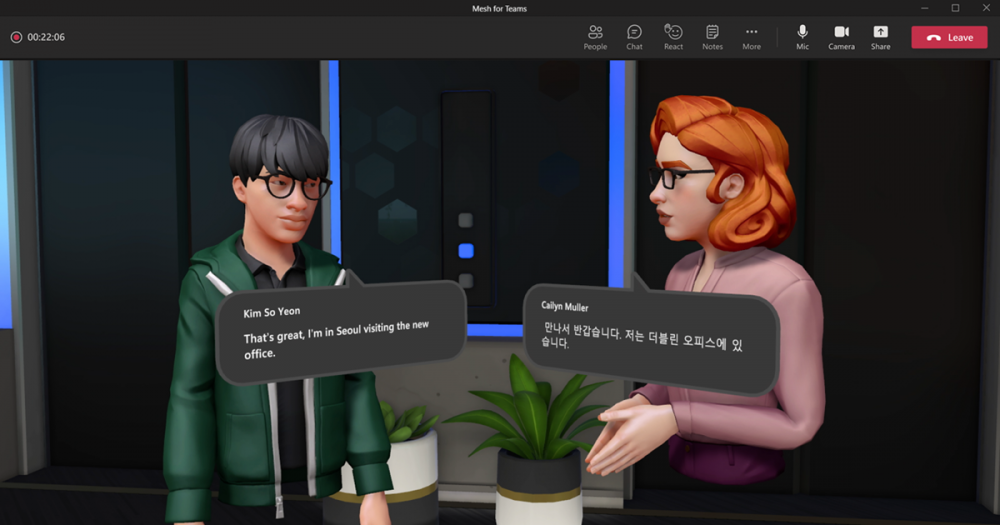

A video introducing a 2D and 3D immersive metaverse called Mesh, due to be launched by Microsoft in the first half of next year, explains: “A metaverse is a digital space inhabited by digital representations of people, places and things. Think of it like a new version – or a new vision – of the internet. Many people talk of the internet as a place – now we can actually go into that place to communicate, share and work with others. It is an internet that you can actually interact with, like we do in the physical world.”

Just as nobody in 1995 could have imagined exactly what the internet would look like today, nobody knows what a fully-developed Metaverse will look like in the future (I’m using the singular for convenience but the expectation is that there will be multiple metaverses that users can access in future). One thing, however, is easy to predict: it will have the capacity to amplify the best and worst of everything that makes us human.

Who couldn’t get excited by the prospect of putting on a 3D headset and being transported into a place of learning or wonderment (in the way many gamers already do)? A brain surgeon on one side of the world might appear as a hologram in an operating theatre on the other to supervise a life-saving operation. A classroom of children might be taken to a primordial world to witness the dawn of life.

You might take a test drive in the car you’re thinking of buying without leaving your front room. You could be trained to operate heavy machinery without endangering yourself or your colleagues on a construction site. And you could walk through a virtual mall, trying on clothes and using cryptocurrency to buy them.

Conversely, who wouldn’t be horrified at the prospect of a child being groomed in a virtual world? Or of a metaverse where visitors could pay to watch – and take part in – virtual violence or exploitative sex? Or of finding themselves in a 3D con in which they lose their life savings to a virtual property scam?

Where you interact with other people and businesses in a metaverse, you will be represented by your avatar, the digital version of yourself. (Avatar is the Sanskrit word for “descent” and it was used when describing the physical appearance taken on by a Hindu deity coming down to Earth). Nobody yet knows whether you will have the same avatar across all metaverse platforms or different ones for each, but you might have to have multiple versions of yourself unless service providers can agree to safely share information about who you really are as you pass seamlessly from one to another.

Already off the blocks in the race to grow the Metaverse are Meta (Facebook), Microsoft, graphics chip designer Nvidia, Epic Games (maker of the hugely successful immersive game Fortnite), the gaming platform Roblox, Cisco, IBM, Gather and a host of others who have already created virtual worlds, such as Decentraland and Second Life (more on this later), or who are developing technology to make avatar movements and reactions more realistic.

This sudden scramble, given wings by Zuckerberg’s Meta rebranding, has largely been generated by the pandemic and the move to permanent or hybrid working from home. The novelty of communicating with colleagues over Zoom soon lost its lustre and was replaced by a desire to have meetings where participants felt more in touch – as if they were in the same room, moving in the same space or sitting around the same table.

Building on Altspace, a 3D social platform launched in 2015, and Teams, its version of Zoom, Microsoft has built Mesh, while Meta has come up with Horizon Workrooms. Both allow immersive 3D experiences with headsets, but they can be used in 2D without them.

Each is sold as a fun and exciting way to interact with colleagues but I found the idea of an isolated individual sitting in a flat and wearing VR goggles in their pyjamas, while their bubbly avatar attended a virtual meeting with other bubbly avatars, rather depressing.

And when Covid-19 will soon represent an annual threat no greater than flu, why spend so much time and effort on hybrid and home-working tech anyway – unless your intention was to save companies vast amounts of money on office space? According to a report by tech consultants Altus Digital Services, remote and flexible working will save companies up to £10,000 per employee, per year in commercial rents.

The technology we’re developing marries the digital world and the physical world by kind of overlaying an internet-like concept. So, if you look at it from that way, then yes, we should learn from what’s happened before with the internet

In fairness, some tech companies had been working on virtual 3D conference platforms even before the pandemic. Katie Kelly, Microsoft’s principal product manager, has been involved in creating what she calls “mixed reality” for six years, including building virtual meeting places where some of IT consulting company Accenture’s 624,000 employees get together remotely as themselves, as images or as avatars. During various lockdowns, new Accenture recruits were given a 3D walk-through of the company’s head office as part of their induction.

“I think we all know intrinsically what we missed during the pandemic, but it was hard to find solutions for it, especially technological ones,” says Kelly. “If anything, some technology kept us further apart. This kind [Mesh] isn't going to be the thing that changes it all. It just adds another layer to the ways that people can communicate, to allow them to feel a little bit more present with each other. What we're giving is with one click, you're able to go from a grid view and transform it into an immersive 3D space. And then you are able to go into a corner and have side conversations.”

Kelly says that clients had started asking for some way to recreate “water cooler” moments, virtual places to share PowerPoint presentations and so on. “My focus has always been on community, on the person level of just how do you offer more ways for people to interact? I think hybrid work is here to stay in some form or another and so I think there’s always going to be a need to offer technology solutions like these.”

In the award-winning 2020 documentary The Social Dilemma, a host of tech experts who had once played important roles in developing social media describe how they had initially believed that it would be a force for good, but how they gradually came to the conclusion that they had created a monster. Focusing largely on Facebook, they said social media manipulated people’s behaviour and emotions, fostered addiction and conspiracy theories, and spread disinformation in order to encourage users to spend more time online, time during which they could be force-fed lucrative advertising.

Similarly, the first internet pioneers probably didn't envisage its darkest uses. Nobody from Facebook would be interviewed for this article. In their absence, I asked Kelly whether the Metaverse might, in turn, be used for nefarious purposes.

“These are definitely the things that keep me up at night,” she said. “Alex Kipman [the lead developer of Microsoft’s HoloLens] said that you can think about the Metaverse similar to the internet. It's more like a 3D version of the internet or a spacialised internet, and the different experiences that you go to are similar to websites. So, you're right; the internet metaphor is really apt for what the Metaverse could potentially be.

“The technology we're developing marries the digital world and the physical world by kind of overlaying an internet-like concept. So, if you look at it from that way, then yes, we should learn from what’s happened before with the internet.”

If we want to learn from the past, we could do worse than revisiting US tech company Linden Lab’s Second Life, a virtual internet world that has been attracting millions of visitors for more than two decades. Here, participants’ avatars can exchange real money for Linden dollars to buy goods, land and property, run businesses selling digital products for the digital avatars, get married, join clubs, play games or just hang out.

It began innocently enough – and continues overwhelmingly innocently to this day – but inevitably, just as in the real world, human weaknesses, desires and emotions sometimes take over. Second Life has experienced revolts against virtual property taxes, been used to host virtual paedophilia communities, had gambling banned in its virtual casinos, had a controversial virtual university closed down and suffered virtual bank collapses. There have even been cases of real-world divorce because of virtual adultery there.

Sky News’s investigations editor Jason Farrell uncovered one of the paedophilia scandals (there has been at least one other), in 2007. He pointed out at the time that the site had 8 million users and so the possibilities for wrongdoing were very real.

The characters had virtual homes equipped with a perverse mix of cartoon videos and sex toys. They could simulate any sexual fantasy they desired. I was as close to seeing inside the mind of a paedophile as I ever wanted to be

“When my editor asked me to create an avatar and investigate crime in this virtual world, it wasn’t long before one user contacted me with a disturbing tale,” he said. “Her avatar, called Harmony, was a winged angel. We met on a virtual island where she told me about the Second Life place called ‘Wonderland’.

“‘It’s a paedophile ring’, she said. ‘They do all sorts of dreadful things’. Wonderland was a candy-coloured children’s playground with a mix of child and adult avatars. The adults were tall and domineering, the children petite but sexually attired in mini-skirted school uniforms. One could only assume the child avatars were controlled by adults.

“The characters had virtual homes equipped with a perverse mix of cartoon videos and sex toys. They could simulate any sexual fantasy they desired. I was as close to seeing inside the mind of a paedophile as I ever wanted to be.” Wonderland was closed down by Linden Lab, but another avatar later gave Farrell a list of 50 other “child play” areas.

Bob Stone, Emeritus Professor in eXtended reality (“XR”) and human-centred design at the University of Birmingham, says he has concerns about the development of the Metaverse on several levels, starting with the risk to investors from dubious 3D start-up companies. He also has concerns over the potential for visitors to become addicted to virtual worlds, the mental and physical health risks of people staying in them for too long, the potential for criminal activity and how that would be policed.

“I’ve been working in the VR community for 35 years and, having seen the dotcom crash in the late 1990s, when so many start-ups were found to be selling overhyped and overpriced services, I’m seeing the same investor bump happening with the Metaverse,” he says.

“All of a sudden, it’s explosive. ‘Oh, the Metaverse will be fantastic, the Metaverse will do everything’, but it won’t. My background is in psychology and human factors, and that, coupled with my VR experience, tells me that, once again, we are seeing an excess of overnight start-ups and self-proclaimed experts. We’re also witnessing premature investment of the order of millions of pounds in companies that have questionable value and which will undoubtedly put glamorous technologies on the market long before they have understood the needs of the end users.”

In a recent paper for the Centre for the New Midlands, which promotes innovation in the region, Stone advised potential investors: “With the vision of many of the organisations, coupled with their undoubted capabilities to deliver, companies in such sectors as defence, healthcare, product development on micro and macro levels, entertainment, education, tourism, finance, broadcasting, and so on stand to benefit from involvement in the future of the Metaverse. Indeed, there may be penalties from those disbelievers who choose to remain behind in the real world.

“But, from the perspective of corporate adoption, what does all of this mean in reality? Well, just like the situation that has existed across XR for many decades – and more so today than ever before – the Metaverse ‘market’ is currently a confused, frenetic and highly risky stage show on an international scale, with no clear indicators of what may happen next.”

Stone said he was particularly concerned about the over-use of headsets, pointing to research by Jeremy Bailenson, founder of Stanford University’s virtual human interaction lab. In his 2018 book Experience on Demand: What Virtual Reality Is, How It Works, and What It Can Do, Bailenson warned of “simulator sickness” caused by a disconnect between the eyes, brain and body. Symptoms include nausea, sweating, dizziness, vomiting and fatigue, and Bailenson says that they can sometimes be delayed. In the book, he described one VR user collapsing at home, long after using a headset.

To avoid such reactions, he advises a maximum 20-minute usage rule for people wearing VR headsets for training purposes, adding that “closer to five to 10 is better”. Yet people using the Metaverse could reasonably be expected to become immersed in it for hours. According to Statista.com, last year, users of the internet averaged 145 minutes per day on social media alone.

The temptation to stay in the Metaverse for hours on end will be just as great, if not greater. And if your avatar builds a better virtual life than the one you have in the real world, you might choose to spend most of your life as your digital self.

What companies could do with 3D technology, headsets and artificial intelligence that can read our behaviour and that can come to understand our unconscious processes better than we understand them ourselves could lead to the kinds of subconscious manipulation that advertisers would pay richly for

“I’m concerned about how such levels of dependency will be used to manipulate your unconscious biases,” says Dr David Harley, principal lecturer at Brighton University’s School of Humanities and Social Science. “The fact that Facebook wants to get so involved in this is very worrying. We know [from internal documents leaked by Haugen] that they have been probing unconscious reactions and mining human behaviour for monetary value since they became a public company.

“They are finally being brought to task over all this in the real world, so now they are moving into the virtual world where they will be less accountable. What companies could do with 3D technology, headsets and artificial intelligence that can read our behaviour and that can come to understand our unconscious processes better than we understand them ourselves could lead to the kinds of subconscious manipulation that advertisers would pay richly for.”

Chillingly, Harley predicts that such immersion could be used not only to manipulate our buying choices, but our life choices too.

“It does all start with manipulating consumerist behaviour – purchases – but as we’ve seen, this is just the tip of the iceberg – if we think about the potential influences to democratic processes, involvement in extremist groups, effects on body image and eating disorders, general mental health for some, then the ‘unintended’ consequences start to mount up,” he says.

“Imagine this: you’re attending a regular staff meeting in one of Meta’s [virtual] Horizon Workrooms. Your boss starts off the meeting with a presentation about their new departmental restructuring. You find it impossible to conceal your dislike for this move which will inevitably result in more staff redundancies. Thanks to the new headset provided as part of your ‘staff wellbeing bundle’ the system registers your emotional reaction as anger and disgust.

“Your boss finishes his presentation and encourages everyone to take part in a collaborative brainstorming activity to explore the benefits of this new organisational structure. You find it really difficult to engage with such a task and instead of joining in you find yourself phasing out and focusing on the beautiful office backgrounds that are in these virtual workrooms. This week they show images of the Norwegian Fjords. The system registers your shift in attention and notes your attitude of non-conformity. You are relieved when the meeting comes to an end.

“Later in the day,” he continues, “you’re scrolling through social media, catching up with friends. Instagram intersperses more beautiful shots of the fjords, adverts for Hurtigruten cruises and appeals from Greta Thunberg to join climate protests. You make a point of liking these posts. Later in the evening, you’re watching TV, and Facebook notifies you of the following: a news story about Greta Thunberg’s recent involvement in climate protests; a heated debate in your local Extinction Rebellion group about the inaction of government, and recent job offers from a number of Scandinavian countries.

“You think back to your staff meeting earlier in the day. In the past you might have taken the issue of redundancies to your union – on this occasion, you think you will just go with the flow and take a job in Norway.”

One consumer psychologist who chose not to be interviewed for this piece sent an email arguing that there simply wasn’t yet enough information on which to base predictions about whether the Metaverse would be harmful. There was “a lot of catastrophising” and not much solid evidence either way, he said. “The Metaverse will like any other technology, either a benefit or a hazard. How we use it will determine which it is.”

But it isn’t our use of it that is ringing alarm bells. It is what form “it” will take, and just how cynical its creators will be to exploit our innate human weaknesses for their own financial or political ends.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments