Mental illness in Italy: the disease that dare not speak its name

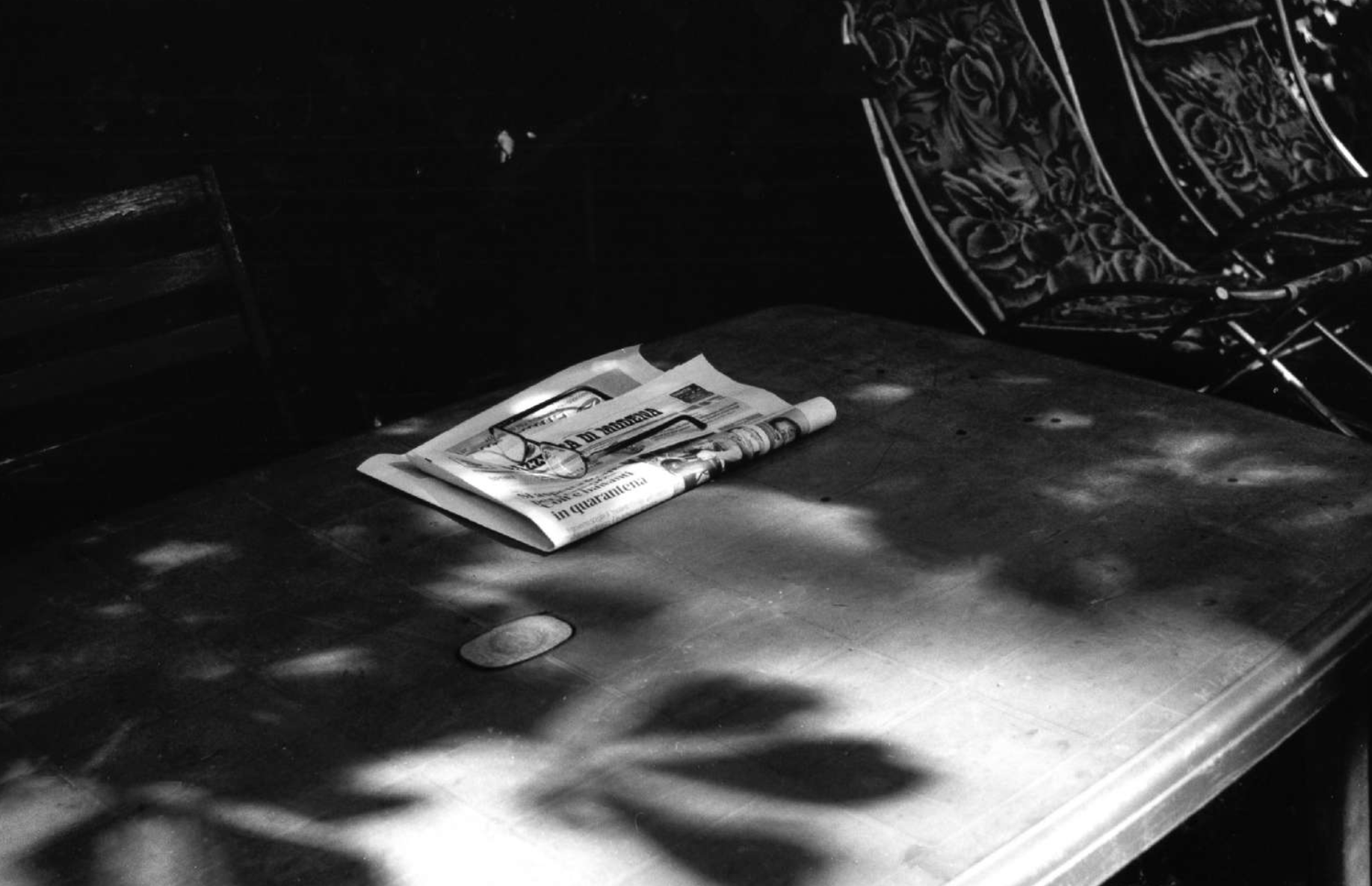

The Basaglia law was supposed to close mental asylums and help patients through local communities. Forty-two years later, that support still doesn’t exist. Instead, people are treated with drugs behind closed doors. Lavinia Nocelli reports

There have been 30 suicide cases this past summer,” says Massimo Mari, director of the district mental health department in Jesi, central Italy, as he runs his hand through his hair, his face marked by exhaustion. “There were 15 in just over two weeks, five of which were in the town of Filottrano. People are not being monitored by our network. We just managed to catch a few of them before it was too late. If I’m short of 19 nurses, 19 educators, 11 psychologists and seven psychiatrists, how am I supposed to work? These numbers are the bare minimum to handle emergencies, but ideally you would need…”

He stops. He is irritated by the situation. His gaze is clouded by the hopelessness of it all. Piles of papers and books tower on his desk, bearing witness to the hard work of the past few months. While his own requests for help seem to be ignored, calls for assistance continue to pour in from the community. Some cannot sleep at night, while others have crippling anxiety or are afraid that death is just around the corner. This is the shadow pandemic: that of mental illness.

Nearly 20 per cent of Italy’s population suffers from a mental disorder, and yet the care provided by the Italian health system barely covers 25 per cent of the psychological needs of the people as laid out by the “essential levels of care” – the services and benefits that the Italian national health service (SSN) is required to provide to all citizens. Meanwhile, the average national health expenditure on mental illness amounts to a mere 3.6 per cent of the available budget.

“The Marche region spends 2.1 per cent; the law states it should be at least twice as much,” says Mari. “As a region we used to rank second to last nationwide: now there has been a nosedive.” Outside, the clouds are building up around Murri hospital, depriving it of the little light left.

Mental health is a thorny issue in Italy, and one which is often not talked about. Personal problems left unaddressed, perhaps because of stigma or a lack of understanding, translate into a cultural, social and political issue. Forty-two years ago, Italy passed law 180/1978, also known as the Basaglia law, named after its chief proponent, psychologist Franco Basaglia. The law closed down all of the country’s asylums – places often seen as tasked with obliterating the individual – and aimed to replace them gradually with community-based services. It was considered a turning point, as Italy endorsed a decentralised type of care, upending the often terrible practices of the past.

However, efforts to establish and develop mental health services were defunded over time in many parts of Italy, thus hindering the effectiveness of the Basaglia principle. The revolutionary momentum of the reforms stalled, turning away from social care and towards drug-based therapy, which then became the mainstay of treatment. Mental illness is now once again treated with prejudice: it is seen as deserving segregation; as crippling and untreatable. In other words, as a private matter.

“Today, psychiatric hospitals have a more chemical nature,” says Mari. “The ill are gradually hospitalised. The more patients you have, the more medications you prescribe.”

An inner asylum

As soon as you set foot in L’Aquila, the capital of Abruzzo in central Italy, it feels like you’ve been punched in the stomach. The beauty that once characterised the city is still in the air, but all you notice now is the traumatic legacy of the devastating 2009 earthquake. The rubble still lies where it fell on that tragic day in April, and nobody dares go near it. The locals no longer seem to notice the collapsed buildings around them.

There’s a disease, so there are symptoms, a syndrome and a pharmacological therapy: only cold calculations, no looking after anyone

“The mental asylum here has been closed down,” says Dr Alessandro Sirolli, the former director of the mental health department in L’Aquila. “But it still inhabits the minds of people. We say this here because a therapeutic community that tells you when to take a shower, have lunch, go for your walk or take your meds is tantamount to a mental asylum.”

I meet Sirolli and his son Emanuele on the rubble of the city’s old psychiatric hospital, now an ancient carcass, where 180 Amici, an association that aims to safeguard citizens’ mental health, was born. It was founded by a group of locals and family members sensitive to the cause. “We strive for a city that looks after and treats its people, made [up] of communities. We implement services that are conducive to this,” says Sirolli.

The urban skeleton behind them captures my attention, lying helpless on forsaken land. “The generation that tried to close down mental asylums and tried to develop treatment is now no more,” says Sirolli, as he shows me the small museum that houses artefacts of the former hospital: barred beds, pictures of the former directors. “The new generation didn’t get to experience this. They are trained in clinics, within psychiatric diagnostic and treatment services – 80-90 per cent of which are exclusively pharmacological and restraining facilities.”

The fragmentary application of the law at a national level led to overburdened services, the overcrowding of patients, and an increasing reliance on the concept of psychiatry. The lack of funds is undeniable, Emanuele explains, but the real problem is how they are used. “The fact is that the departments are not what they were supposed to be, namely a well-organised system of services that put the patient at its centre, aimed at planning their recovery with them from a condition of suffering.

“There’s a disease, so there are symptoms, a syndrome and a pharmacological therapy: only cold calculations, no looking after anyone.”

“Part of the problem emerged in 1994, when healthcare treatment and social care was split apart. Before then there used to be local social health units,” says Emanuele. This split enabled the separation of funding, with the former doing better financially than the latter.

Sirolli knows there is a lot more to do, because nobody knows how to detect misery, filter distress, or build a dialogue for a prevention process. “You can only take action if you work at a social level, not in terms of health, otherwise you are only engaging in early intervention.”

The face of madness

The network of services coordinated by the department of mental health in the centre of Naples is home to countless inner-city stories. Antonio is a social facilitator, a person who suffered from mental illness in the past and now helps patients. He speaks fast, very fast, as if his words might try to escape before he can finish his sentences. The voices in his head used to warn him that his food and water were poisoned and that if he went to sleep, only death awaited him. He explains to me that medication is crucial in the early stages to silence the voices. However, the patient is “completely knocked out, as if they were hit by a truck”.

Reforms have taught us that it is the synergy between the clinic and life that truly matters. Very often, ‘extraclinical variables’ are more important in a story

Antonio once relapsed – he hesitates a little when he tells me this – but the episode was temporary, he says. Social rehabilitation, moving from a safe environment back into the outside world, must be a gradual process: “I’ll take your hand and, based on how you feel and on what stage of the illness you’re at, I’ll give you some suitable solutions to go back out there and successfully reintegrate into society,” he says. However, there is no such process at the moment, and Antonio warns that one should “never over-glorify medication”.

To give an idea of what mental illness really means in Italian society, imagine that you are looking for a job. Employers might prefer physical disability over mental disability, because they are not familiar with mental illness and see it as something frightening and hard to manage, and perhaps as something that will bring additional costs. This in turn has a knock-on affect on an applicant’s mental health.

In his role as a social facilitator, Antonio creates customised projects aimed at building bridges between the two worlds, but there is much that needs to be done, and many decisions need to be made. He believes that what is needed is a political project, to improve our care system. There is a broader concept of recovery with which only professionals are familiar, and that is the idea that only those who have suffered mental illness can fully understand it. Often, people do not understand what they cannot see: that is the great deceit of mental illness.

The devil’s advocate

Private can mean many things, most of them relating to a single individual. It goes well with words such as “personal”, “intimate” and “family”. In Italy, mental illness is often kept hidden, and is dealt with within one’s immediate family. Now, though, external factors are adding to the shame experienced by sufferers: the absence of local, public-sector help, and being denied the right to treatment.

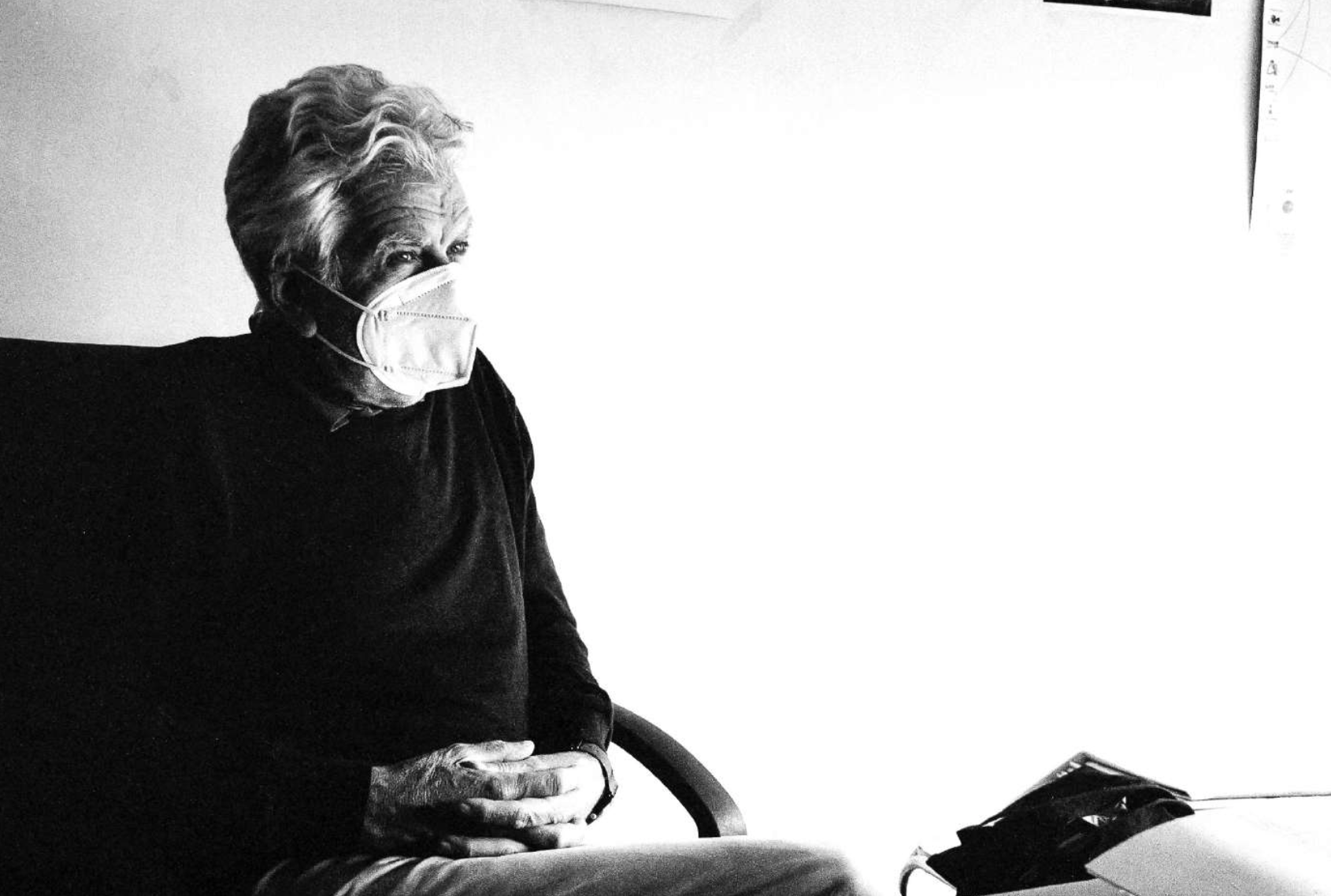

The streets of Naples are an endless traffic jam. Mopeds swerve between vehicles, jumping the queues, while the words of passers-by are muffled by face masks. Fedele Maurano, the director of the district mental health department, asks me if I would like a cup of coffee, and we take a seat. It’s his fourth, maybe fifth today. A crisis is under way, and many inconsistencies need to be addressed – personal relationships and life, social relations and social distancing. According to Maurano, Covid is teaching us that freedom is no individual matter: that you can’t save yourself on your own.

The building we are in overlooks the city. I can see its people: tiny dots moving quickly, full of life. Maurano tells me about the 11-year-old boy who jumped off a balcony the previous day. “It’s emblematic,” he says. “We can’t grasp what harm a teenager may endure if they cannot go to school, or if they have to leave their family and enter a different world. Italy invests very little in mental health services for children and adolescents.”

Maria Grazia Gianichedda tells me that Covid hasn’t exacerbated people’s illnesses but has made the problems more visible

What’s missing? “Resources. The welfare state has been dismantled,” he says. But health doesn’t only depend on healthcare systems. “Reforms have taught us that it is the synergy between the clinic and life that truly matters. Very often, ‘extraclinical variables’ are more important in a story, the ones you can’t imagine.” Their effects are tangible and powerful, for example a hug in times of deep suffering.

“What is the underlying concept of mental health?” Maurano asks himself. “You teach a student what the illness is, how to treat it, how to get a medical history.”

According to him, at university they don’t teach students about the reform, or what Law 180 ultimately is. The loss of awareness of mental health is due to a comprehension bias, what we understand over what we do not: we tend to acknowledge a tumour far more easily than depression.

The colours of autumn cover the pavement when I arrive in Milan. The cool air is a reminder of the imminent curfew; the rain is silent. “Basaglia is playing the devil’s advocate, some politicians claimed in old interviews. ‘How could you pass this law?’” says Roberto Mezzina, the ex-director of Trieste’s mental health department and a current WHO (World Health Organisation) adviser. His voice gets deeper when he remembers the concerns and criticisms of the past. “‘You know Italy is not ready for this. Do you seriously think Italy can take such a major cultural leap?’ Enforcing that reform meant upholding human rights, because that was a political choice against oppressive institutions – with its challenges of course, but nevertheless necessary to uproot the mechanism underlying that stigma, namely attaching a merely objective nature to diseases.”

Mezzina believes that mental illness will overtake heart disease, and that depression will be the most prevalent illness by 2030.

“It will cause as many absences from work as cardiovascular diseases,” he says. “Now, from the outside, I realise that unfortunately we failed to create a formal approach, a real school of thought. Basaglia was wary of developing more rigid models, crystallising them, avoiding institutionalisation. Committing someone is no longer condoned by society; this is no small matter. Don’t underestimate it.”

A patchy distribution

Some mornings during the pandemic I would wake up feeling as though I was in a different body, completely unknown to me, and with a chaotic mix of leftover dreams running through my head. One night I imagined a giant hole in my chest; I felt my heart racing and experienced shortness of breath. Massimo Mari says that it’s the same for everyone, and that one shouldn’t make a big fuss about it. The news never stops, as though death hands us a bill every night – “That’ll be 530 deaths today, Sir.” You just need to avoid letting it get to you.

Maria Grazia Gianichedda says Covid hasn’t exacerbated people’s illnesses, but it has made the problems more visible. She says all the problems in mental healthcare provision – political inaction, poverty, funding – were already there, and that Covid just laid them bare for all to see. As president of the Basaglia Foundation, she doesn’t have to find a solution to these particular issues: the decision makers from the relevant services are supposed to. “I am part of a struggle that set a historic milestone, the Basaglia law. But no achievement is permanent.”

The Italian healthcare system is patchy. If you look at it, you see that there are some lively and committed areas within the country, and others that are faded and disconnected, where stigma and prejudice are tied to low-quality services. There are no satisfactory answers, but according to Gianichedda, regionalisation has been carried out incorrectly. Instead of helping with provision, “20 little healthcare republics were born”. The laws being in place aren’t enough, she says: passing a law and enforcing it requires both political action and social struggle.

I sometimes talk to friends and they say: “I wake up at night, I can’t sleep.” On television I see reports of crimes in the Veneto region, in Lazio. I watch interviews with shocked inhabitants of devastated communities.

I grab the remote, press the power button to silence the reporter, and take a deep breath. What if one day I wake up hearing voices?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments