There’s something about Marianne Williamson

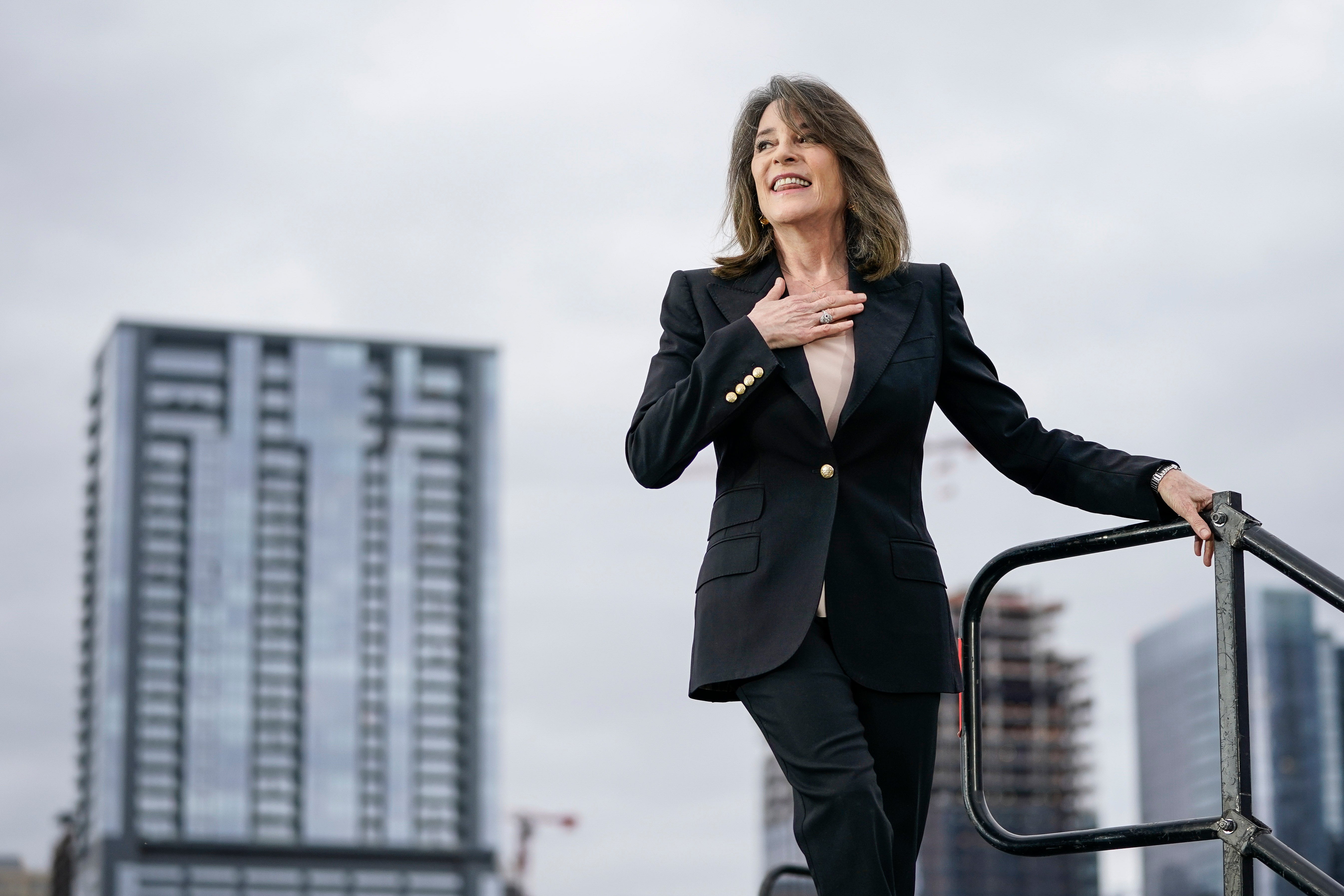

Andrew Naughtie wonders if elements of the ‘Williamsonism’ political philosophy are worth exploring, despite the author and activist often being ridiculed for her ideas and the way she expresses them

I am shivering slightly in an over-air-conditioned cafe in London, dreading the hottest day on record, and Marianne Williamson is telling me I have no choice but to be a doula.

“People get it,” she insists, identifying both the calamity and the possibility of the current social moment with total certitude. “One world is crumbling. You can’t deny it, you have to be in such denial or so foolish not to recognise that one world is dying, but at the same time, another is struggling to be born.

“And we’re called on to be death doulas to what’s dying and birth doulas to what’s struggling to be born. That is a serious responsibility.”

Not many politically-minded people would convey the gravity of our global crisis by plaiting a paraphrased Antonio Gramsci quote together with the vocabulary of the natural birth movement, but these are just the raw materials Williamson works with.

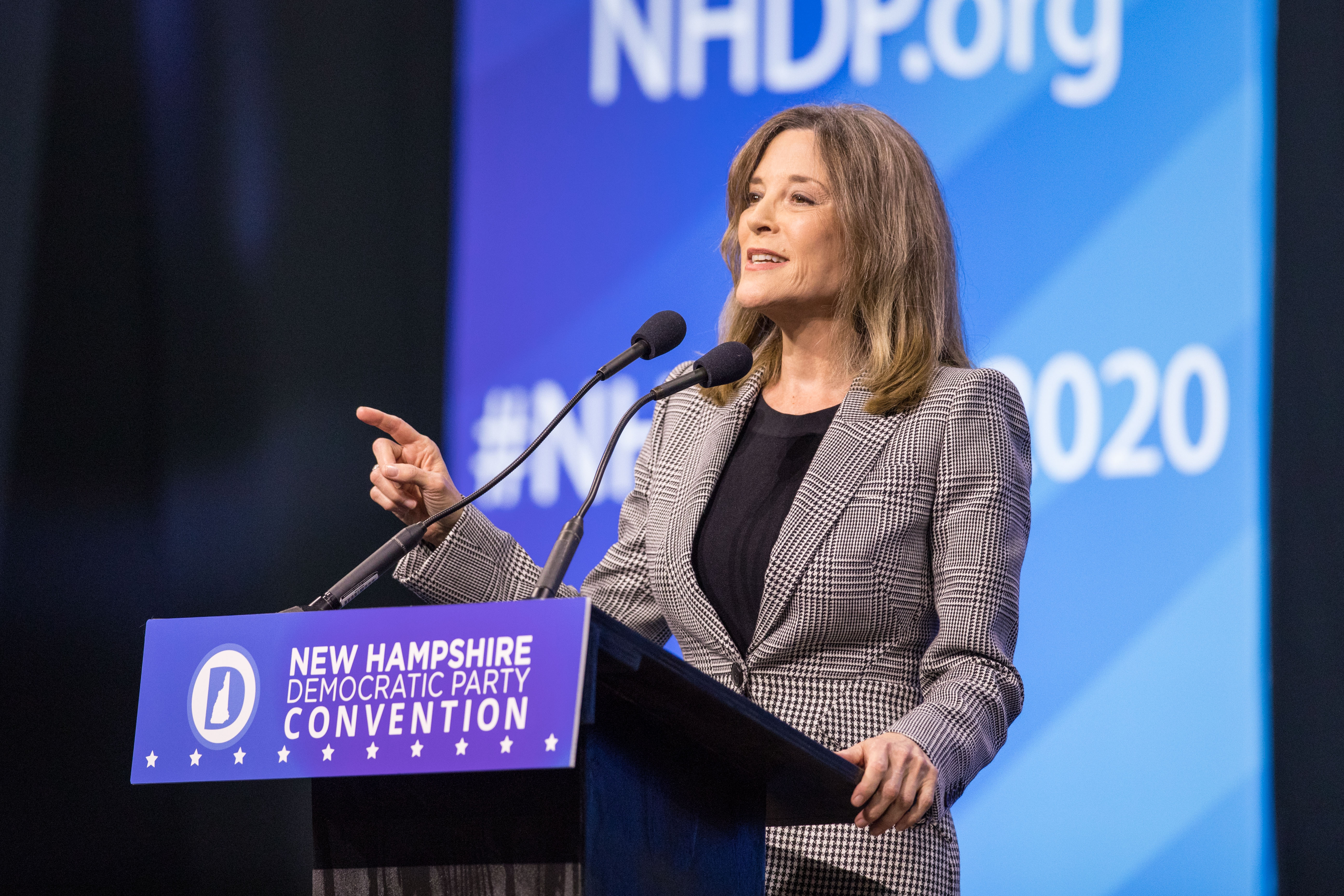

It’s what she took into one of the most idiosyncratic major-party presidential campaigns of recent times, a 2019 run for the Democratic nomination that saw her briefly break into the political-media ecosystem before being run out of it just as fast. And it’s what she carries around the world today predicting the coming of a new human age – as she does at length to me.

Williamson is, to put a fine point on it, a millenarian, increasingly convinced that the old order is failing and is about to be overturned in a spectacular bottom-up transformation of human consciousness and political-economic structure – two things she sees as inextricably entwined.

“The traditional Christians say it was going to be an apocalypse, a great reckoning, and after that, there would be a thousand years of peace. Well, you don’t have to be a Christian to have a more metaphysical interpretation of that.

“For some people, their apocalypse was their divorce. For some, another course of their apocalypse was having to get sober. For another person, their apocalypse was their bankruptcy. For another person, their apocalypse was their cancer diagnosis. And that’s what these countries are going through, they’re going through these upheavals.

“None of us are becoming enlightened masters because of these things. But if you become a wiser man. A deeper man. And I become a wise woman and a deeper woman, if somebody else because of what they went through, becomes wiser and deeper, then we get collective wisdom.”

This is the fundamental conviction underpinning Williamson’s political thought: that the personal and the political, the tangible world and the spiritual world, are fully integrated, and that with enormous pressure on all fronts, “Something Huge Is Happening” – something so big, so unstoppable and so profound that established politics, economics, social mores and ideologies are incapable of fully comprehending it, much less surviving it.

“There is going to be a time,” she insists with a smile, “where masses of people are going to recognise that the entire neoliberal corporate-based experiment was a spectacular failure. This will occur. This will occur. And the only question is, will we make the transition through joy or will we make it through pain?”

Every generation gets to individuate, just like every individual does, and every millennium. The 20th-century mindset is in many ways unsustainable

It’s impossible to sit across a table from Williamson for an hour and not be caught up in her sense of almost messianic conviction. But given her undue reputation for flakiness, what’s really striking is the degree of control she maintains.

Williamson’s vocabulary might be a spiritual, new age-tinged one, but her concerns are not in the slightest bit ephemeral or ethereal. They are real and urgent crises: racism, poverty, inequality, the rapacity of the military-industrial complex, the devastation of the earth, and the existential crisis of democracy.

She recently turned 70 and is every bit a woman of her political generation, still citing Bobby Kennedy as her hero and holding up the nonviolent activism of the civil rights movement as the ultimate form of American political action.

This brand of radical boomer has always been her political stock-in-trade, and she has spent years calling on her contemporaries to rise to the apocalyptic challenge they don’t even realise they face.

“We will end this chapter in American history,” she told a theatre of supporters in Los Angeles while running for president, “and we will usher in a new chapter, something exciting, something new, something amazing, and future generations will look back at us and say, ‘it’s a mystery in history! Who would have thought it? This generation that seemed to not care about anyone but themselves, all of a sudden at the last minute woke up and remembered: I am not here alone!’”

But her faith is now placed in the rise of an entirely new cohort.

“Gen Z is fascinating to me,” she smiles, reflecting on the college speaking engagements where she gets rousing applause from students only just old enough to vote. “I was saying to someone jokingly the other day, these kids were raised by mothers who read the kind of books that I write.

“They hear me when I tell them, ‘you’re not 20th century people, you should not live your lives to the effect of bad ideas left over from the 20th century,” she says of her younger audience. “Every generation gets to individuate, just like every individual does, and every millennium. The 20th-century mindset is in many ways unsustainable, and ‘unsustainable’ is in many ways a soft word for a very harsh reality. It means ‘unsurvivable’.”

It’s this aspiration to fully connect people’s spiritual and political consciousness that distinguishes what you could call “Williamsonism” from other political methodologies – including the various shades of historical materialism, progressive wonkery and borderline anarchism that jostle together on the American left writ large.

What’s changed since her campaign, as she sees it, is that the epochal consciousness shift she’s been predicting for years is here – and it’s moving in her direction. Even if it is sometimes difficult to take her words as seriously as she wants given the way they can be expressed, as she herself recognises:

“There was a time,” she muses, “when the spiritual types were prone to saying, ‘I like her, but I just wish she’d shut up about politics,’ and a lot of the political types would say ‘I like her, but I just wish she’d shut up about the Tao and spirituality and love and forgiveness’ – now, there’s a melding in the culture.

“People realise that just addressing the symptoms of our problems in this mechanistic way is not an adequate problem-solving modality, it’s not a Newtonian world where the world is just a big machine, all we do is put the pieces in the machine. It was the British physicist James Jeans who said, ‘It turns out the world is not just a big machine; it turns out it’s one big thought’.

“And the many in the spiritual community as well realise that this is not a moment where any conscious person could justify an apolitical posture. There’s no religious tradition that gives anyone a pass on addressing the suffering of other sentient beings.”

A lot of people got Williamson wrong when she ran for president – me included. Like endless others covering the drudgery of the early Democratic primary, I watched her performances at the two overstuffed debates she was allowed into and grinned, seeing a chance to write a snarky, snappy piece about the teal-clad new age thinker whose musings on love, hate and Jacinda Ardern had left everyone baffled.

But – to me at least – Williamson had much more going on than I had bothered to notice. I started to grasp this pretty quickly, compulsively paying attention to her even after she was shut out of the debates, polling in the lowest of single digits and raising comparatively sums of money.

Some others were at least genuinely intrigued. Stephen Colbert, Seth Meyers and Trevor Noah all hosted her in their late-night slots. Kara Swisher, one of Silicon Valley’s most unsparing interrogators, gave her a warm and genuinely inquisitive welcome on her podcast.

Writing in the National Review, the anti-Trump, anti-abortion Christan conservative Kathryn Jean Lopez mused that with her ability to give voice to the profound anomie and angst afflicting the American body politic, “Marianne Williamson could win the Democratic nomination.”

“Like Trump,” Lopez wrote, “Williamson is not the problem or the saviour, but she shows us something about our poisonous culture (even if she misses some big problems, like the way we treat some of our most vulnerable – a Marianne Williamson opposed to abortion would be a fascinating campaign). The antidote is not in a political ticket, but the way we live our lives.”

Even putting aside her unusual political bent and the cruel financial and political realities of how candidates are winnowed out, Williamson has other quirks that made her 2020 campaign a tall order.

Her speeches in small rooms in New Hampshire and Iowa, or at the Yale Political Union, were slow-brewing, cathartic sermons that reliably drew spontaneous applause and rousing standing ovations, but she was less effective at full-blown rallies. She occasionally trips on her own intricate phrasings, and if she pushes her husky and soothing voice too hard, it cracks into a strained yodel.

What happened in my country in the 1960s proved if a whole culture change is only led by soloists, they can deal with that just by shooting the soloist. This is a song now. They can’t shoot a song

She also had not grown the almost inhuman carapace that top-level candidates need to endure the atmosphere of relentlessness that has become the test of a future president. It’s sad that a stony imperviousness to upset is considered a key qualification for the US’s highest office, but that Williamson was appalled at the way she and others were treated was inevitably read as just another sign that she was somehow less than serious.

Given that she has made a career telling people how to recover, forgive and move on, the disappointment and insult of the campaign was a different test for her than it is for the everyday losing candidate.

Her disgust at the political establishment that she believes conspired to crush her – and so many others – now runs very, very deep. And now, years later, when the election comes up in our conversation, I can see a real tension creep into her face.

I mentioned to her a long-ago Oprah appearance I stumbled upon where she recommended that if you’ve been wronged by someone, you should pray for them every day, and asked her how she had gone about forgiving the people (implicitly, people like me) who had helped take her down.

“You get bitter, or you get better,” came the answer. “I think people observe how someone loses. Strong people fall, but strong people get back up. And none of us want to be known for the chip we carry on our shoulder, right? My father used to say that living well is the best revenge.”

So what now? Williamson clearly will not be drawn on whether or not she’ll run for president again, but given how galling her experience was, it’s hard to imagine she wants to repeat it. Even if she did, the challenge for a Democrat running against Joe Biden in 2024, or even just to succeed him, will be radically different than it was in 2020.

Any hungry and angry progressive who decides to shake up the 2024 field will need not just the hide of a rhinoceros, but the ability to convince Americans that they can actually solve the country’s all-too-material problems, not just its spiritual malaise. Technocracy is far from Williamson’s speciality, and she knows it; her first answer at her fateful first debate performance was a warning that simply having a plan would never beat Donald Trump.

Yet today even more than three years ago, she considers the challenge and the opportunity of the moment far greater than any bill, or any election, or any one candidate can accommodate.

“The revolution of this moment is not to be led by soloists,” she says, just after musing that somewhere in all the cement around us there must be growing a tiny flower. “What happened in my country in the 60s proved if a whole culture change is only led by soloists, they can deal with that just by shooting the soloist. This is a song now. They can’t shoot a song.

“So, if enough of us bring forth our best – not perfection, but our best – then we will course correct, sooner rather than later, and through joy instead of pain. And I see a fire burning in enough people’s hearts. And that’s what gives me hope.”

You can tell a lot about a person by reflecting on the way you feel after you leave their company. I arrived for our interview not knowing what kind of conversation I was getting into. I left feeling almost elated, convinced not that Williamson would ever be president, but that she is possessed of a political edge others should envy – and that while I still cringe at some of her more purple vocabulary, her conviction, her moral certitude, and her sheer ambition for the human species are not just narcissistic ramblings, but earnest calls to the sort of radical political transformation that too many of us have grown too cynical to imagine.

“From abolition to women’s suffrage to the civil rights movement,” she declares, “generations before us have pulled off miracles. Why shouldn’t we?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments