A male contraceptive gel is in the works but gender equality in sexual healthcare is still a slippery slope

This pioneering birth control could redress the balance and see men sharing the burden of contraception, but it won’t hit shelves for another 10 years and until then it’s still uncharted territory, writes Georgina Roberts

It’s 10.30pm in the town of Lynnwood, Washington state, and 30-year-old Michael Sworen is beginning his nightly bedtime ritual after a long day’s work as a sous-chef. The restaurant job helps pays the bills, but he and his wife Nic have also set up a children’s illustration business, Merlion Illustration, which they hope will one day allow them to stay at home with their little girl. The family celebrated their first Mother’s Day in May, with daughter Emelia kitted out in a pink leotard that read “Mom’s First Mother’s Day”.

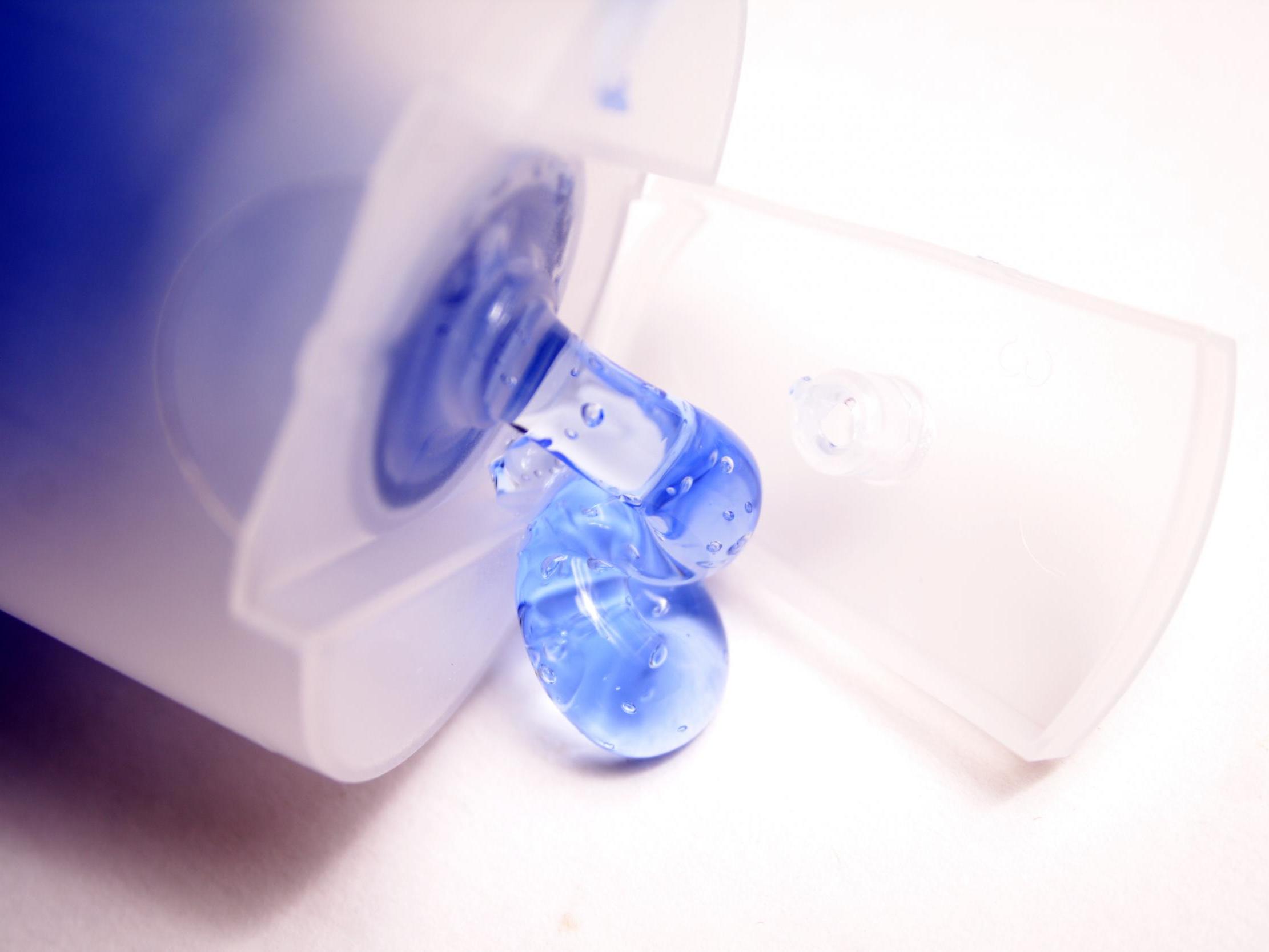

With 11-month-old Emelia asleep and Nic in bed, he showers, combs his hair, then reaches for the tube of gel between his toothbrush and deodorant. He squirts a teaspoon-sized amount of the gel on each shoulder, blends it into his chest, waits 30 seconds and puts on an old, grey Los Angeles Lakers T-shirt before heading to bed himself.

Inside the nondescript tube sitting on the Sworens’ bathroom cabinet is a gel that could change the lives of millions of men and women across the world – a male contraceptive. It has been more than half a century since the first birth control pill was approved for women but, while there are 15 female contraceptives on the market, for men there are just two: vasectomies and condoms.

Six decades later, the pill is still the most popular option. Some 44 per cent of women prescribed contraception choose to take the pill, a total of more than 3.1 million women in England between 2017 and 2018. Despite its prevalence, weight gain, low sex drive, depressive moods or anxiety attacks have long plagued women who take it. A Danish study published in November 2016, the largest of its kind, linked women who use hormonal contraceptives with higher rates of depression. Researchers at the University of Copenhagen, who followed more than a million women aged between 15 and 34, found that those taking a combined oral contraceptive pill were 23 per cent more likely to take antidepressants. Those using progestin-only pills (“the mini-pill”) were 34 per cent more likely.

For the Sworens, too, who celebrated their eighth wedding anniversary in August, there had been problems with the pill. Michael’s 32-year-old wife Nic stopped taking oral hormonal contraception due to suffering mental health side effects. Myriad pills and the Depo-Provera shot produced a “lack of sex drive, increased moodiness, higher aggression, mood swings, sometimes I was severely depressed,” she says.

The tri-monthly shot’s effects were so dramatic that they forced her to call in sick to work, as a scrum master at online children’s maths learning company DreamBox Learning. “I would get really sick for a couple days,” she says. “I wouldn’t want to be touched and it would feel like chaos inside my skin.” But without fail, her mood would “mellow out” when she stopped taking birth control. “When you’re young you have no idea what’s normal,” she says.

Mood changes is one of the top reasons why many women stop using the pill in the first year, a 2013 study found. This backlash has seen a turn toward newer alternatives – controversial contraceptive apps or LARCs (long-acting reversible contraceptives), including the copper coil, the injection, the IUS (intrauterine system) and the arm implant. In England between 2017 and 2018, 16 per cent of women were prescribed the implant, while 9 per cent were prescribed the contraceptive injection and 16 per cent were prescribed an IUD or an IUS, which includes “the coil”.

However, unlike the pill, which needs only a prescription, implants and intrauterine devices have to be fitted by a health professional. This asks women to make a medical intervention which isn’t medically necessary, to endure discomfort, pain and health risks because there are limited other options to prevent pregnancy. Some patients report internal pain during a coil fitting, dizziness, lasting intense cramps for days, and irregular or heavy bleeding.

One of 53 couples taking part in the trial so far, Michael and Nic, have been using NES/T gel as their sole form of contraception since November last year

The situation is complicated by government funding cuts to the NHS, which have put pressure on sexual health services and left some women waiting up to a month to get a LARC fitted, delays which can lead to accidental pregnancies. Not only contraceptive access, but also future abortion access could be imperilled, in light of Alabama’s abortion ban in May.

But this contraceptive gel being tested by the Sworens could redress the balance and see men sharing the burden of contraception. The promise of a male contraceptive pill has been discussed for decades – but with little success. A major obstacle is that testosterone “does not enter the body well in pill form”, according to Allen Pacey, professor of andrology at Sheffield University.

It is metabolised so quickly by the liver that two or three daily doses are necessary. There have been positive signs in recent months, however – in March a once-daily capsule was found to reduce sperm count with no significant side effects. Adverse side effects including acne, aggression and increased libido were enough for the World Health Organisation to halt the 2016 trial of a male contraceptive injection.

As an alternative to pills and injections, the gel being trialled by the Sworens allows testosterone to be absorbed into the bloodstream through the skin. The contraceptive, called NES/T, is a combination of testosterone and progesterone that suppresses the body’s production of sperm. One of 53 couples taking part in the trial so far, Michael and Nic have been using NES/T gel as their sole form of contraception since November last year.

Self-applied daily, NES/T feels like “aloe you put on a bad sunburn”, says Michael. It was put forward as a viable option five years ago because oestrogen and testosterone gel was already a product used in hormone replacement therapy.

There are also 19 couples in the UK taking part in the trial for two years through the universities of Manchester and Edinburgh, where researchers monitor sperm counts, side effects and unplanned pregnancies. Dr Cheryl Fitzgerald, consultant gynaecologist at Saint Mary’s Hospital, is leading the trial in Manchester. Like the Sworens, the first Mancunian couple decided to trial the gel due to pill-induced anxiety. They “felt it was right that the responsibility can be shouldered by either partner”, she says.

Trial participants’ sperm is effectively “sent to sleep” by the gel’s progestogen, which tells the brain’s pituitary gland to switch off sperm production. Testosterone is added in to balance out a drop in the male hormone caused by progestogen. Although the first Mancunian couple have dodged side effects and are “tolerating it pretty well”, it’s a delicate balance, she says.

If the man doesn’t absorb enough testosterone from the gel, it can cause libido loss, mood changes, hair loss or fatigue, Fitzgerald warns. On the other hand, if too much testosterone is absorbed from the gel into the bloodstream, it could cause aggressive moods or weight gain. Michael admits: “I’m pretty concerned about the side effects of the testosterone in the gel, like mood swings or fits of rage.”

At first his wife was “nervous knowing that it was a hormonal birth control after I’ve struggled with severe mood swings,” she says. Her fears were intensified as “we were already under a lot of stress as a couple, as new parents”. She had “a lot of concerns about heightened aggression or mood swings and how that might affect him, myself or our daughter”.

Another risk factor is the gel could give family members hormone imbalances, if they receive a secondhand dose of testosterone from touching the man. Therefore, they are told to avoid skin-to-skin contact for four hours after gel application, which is why Michael wears a T-shirt to bed.

I have to laugh here because it’s going to sound like an advert, but he’s gained more muscle mass, and lasts longer in bed. Hear me when I say we’ve been together for 11 years and it was only after the gel that any of this started

But after eight months of daily use, Nic jokes that any side effects have been positive. “I have to laugh here because it’s going to sound like an advert, but he’s gained more muscle mass, and lasts longer in bed,” she says. “Hear me when I say we’ve been together for 11 years and it was only after the gel that any of this started.”

In theory, the gel is reversible; when men stop taking it, their sperm counts should bounce back from zero to 15 million to 200 million sperm per millimetre, which Fitzgerald classes as normal. However, there is a risk that their sperm count could remain at zero permanently, and the men would be left permanently infertile. Despite these concerns, Pacey says “the only question is how quickly sperm production will begin again”, rather than if it will at all.

Michael isn’t worried by the possibility of infertility as a permanent side effect of the gel. “It’s always a concern that we wouldn’t be able to have another kid, but that’s just one of the risks that we’re willing to accept,” he says. “If we don’t have another kid that will be totally fine with us. It’s not the end of the world if my sperm count doesn’t come back up.” Accidental pregnancies have crossed Nic’s mind. “I have moments where I get nervous about the effectiveness,” she says. “But we have one beautiful little girl together and if I wasn’t willing to have more I wouldn’t be participating in the trial. If it happens now, we would only celebrate.”

The urgent need for more diverse male contraceptive options is evident from the numbers. Between 2006 and 2016, the number of vasectomies in the UK fell by 64 per cent, leaving condoms the most popular method to use by far. Each year, 85 million pregnancies (40 per cent of all pregnancies) are unplanned worldwide, and worldwide 25 million unsafe abortions (performed by untrained people using dangerous methods like inserting foreign objects), according to the World Health Organisation.

Would men actually want to take on the daily chore and side effects of contraception? National attitudes are shifting, according to a January YouGov poll, which revealed that one in three British men would be keen to take a pill. Of those surveyed, 80 per cent see shared responsibility of contraception as a positive development. “There’s been several studies which show there’s been willingness and interest from men to use the gel, or to use a male contraceptive of some kind,” says John Reynold-Wright, a researcher leading the gel trials in Edinburgh. One global survey of 9,000 men from 2012 found 55 per cent of respondents would try “a new form of hormonal contraception”.

Despite this, the largest hurdle has been that “previously the pharmaceutical industry has not been interested in male contraception because of various concerns over how many people would use it”, Reynold-Wright says.

Another hurdle is whether women feel they could trust their male partners to remember to take a contraceptive every day. Half of women surveyed in the UK – 70 out of 134 – would worry that their male partner would forget to take a pill, a 2011 study by Anglia Ruskin University found.

It’s a shame for men that they haven’t been able to take control of fertility, as women have. Nowadays, men are responsible for their baby, so they need to have control too

“It’s a shame for men that they haven’t been able to take control of fertility, as women have,” says Fitzgerald. She believes the gel signals a step towards gender equality, as “nowadays, men are responsible for their baby, so they need to have control too.” Nic agrees: “I want men to have an option to protect themselves from an undesired pregnancy and take responsibility for birth control.”

The results, expected in 2022, will determine whether the NES/T gel should receive the Food and Drug Administration approval it needs before it can reach the commercial market. Reynold-Wright predicts with high hopes that the gel “is the furthest ahead out of the pill and the injection. By the end of 2020s we will hopefully see the gel come out.”

The gel will be on shelves in 10 years’ time, but “it would have to be prescribed, it could be just like the pill for women”, says Fitzgerald. Price-point is uncharted territory, as although the hormones themselves are cheap, the production, without the support of pharmaceutical companies, could be expensive.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments