One for sorrow, two for joy ... magpies are far from black and white

Scavenger, predator, thief or bringer of good fortune? Whenever David Barnett sees a magpie he salutes it. But there is more to this much-maligned corvid than meets the eye

For as long as I can remember I have been fascinated by magpies. There is no rhyme or reason for this. I never had a notable encounter with a magpie as a child nor saw one at an important juncture in my life. I simply feel a strong and magnetic affinity with what is both one of our most mesmerising yet much-maligned birds. So I decided to find out why.

First, the science bit. The magpie’s scientific name is Pica pica, and it belongs to the crow family of birds, or corvids. On average, magpies are around 45cm from beak to tail, with a wingspan of around 52-60cm. There are 600,000 breeding pairs in the UK, according to the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, which gives it a conservation status of “green”, meaning the birds are not under threat.

What else does the RSPB say about the magpie? “With its noisy chattering, black and white plumage, and long tail, there is nothing else quite like the magpie in the UK.” Well, that’s a good start in terms of my vague and unformed attraction to them – it is a unique bird. “When seen close up, its black plumage takes on an altogether more colourful hue, with a purplish-blue iridescent sheen to the wing feathers and a green gloss to the tail.” This is possibly one of the most beautiful aspects of the magpie, as its monochrome silhouette becomes so subtly colourful the closer it gets.

“Magpies seem to be jacks of all trades: scavengers, predators and pest destroyers, their challenging, almost arrogant attitude has won them few friends.” And there it is. The thing that makes the magpie the most Marmite of British birds. Magpies; you love ‘em or hate ‘em.

Andy Bowd loves them, or at least he loves one particular magpie: Sophie. And Sophie has her own insanely popular Twitter account (find her at @breesophiebree) with 47,000 followers, and has lived with Andy and his wife Sheryl almost since she was hatched a decade ago.

Andy says, “She was stolen as an egg by kids, and when she hatched, they dropped her on a local RSPCA volunteer. While that volunteer no doubt saved Sophie's life, they didn't have the skills to not imprint baby birds onto humans. Sophie lived the first four months of her life in a parrot cage in the person's living room with visitors coming and going – TV on that sort of thing.

“So by then the damage was done, she was firmly imprinted on humans. Fortunately, the volunteer must have been cool, because Sophie has always been a very friendly bird. I get the feeling she had a very strong ‘who's a pretty birdy?’ upbringing.”

Andy and Sheryl already had a rook, Rory and Conn, a crow, that they had rescued and lived with them in an aviary in their garden, so they were a natural port of call when it came to rehoming Sophie.

“I took some persuading,” says Andy. “It was Sheryl that wanted another corvid. I set up an aviary in our box room so we could house Sophie over winter. We got her in August 2010 and she was living outside by the following May.

While Sheryl was the one with the affinity for corvids, Sophie “chose” Andy. He recalls, “In Sheryl's mind, we'd get home with Sophie and she'd hop out of the cat carrier and go to her. But that didn't happen. I think we had maybe two days before Sophie made her mind up and chose me. It's been me all the time since. Sheryl doesn't get a look in, and if I'm in the aviary with Sophie, it can get a bit pecky if Sheryl is in the garden and gets too close. It's like Sophie can't get to her to peck, so I get pecked instead.

“We just clicked. We gave Sophie a clear choice in the first days, we both stood in the room with her, and let her go to whoever she wanted. She just picked me. I still don't really understand why Sophie chose me, before I really knew what was happening, she was bringing me sticks and sitting on my hand. I still do catch myself sometimes, as she dozes on my hand, or brings me something.. How lucky I am to share this trust with her.”

Andy knows of three other people that have had similar bonds with magpies. He says: “I spoke to a kitchen fitter a few years ago at my office, and he had a wild magpie friend that would sit in his bicycle basket and go to school with him. He mentioned it after seeing my phone lock screen. And true to his word, he came in the next day with a black and white photo of a him with this magpie happily sitting on his shoulder. I think because they’re so clever, they’re able to reason and work out which human is going to be cool.”

Another human who forged a bond with a magpie is Charlie Gilmour, whose book on the subject, Featherhood, is published this month. Gilmour found a young magpie that fell from its nest in a Bermondsey junkyard and changed his life.

So it’s unusual, but not rare. And it isn’t just people that magpies bond with. My cat Maurice, who will eviscerate a bird as soon as look at it, once forged a friendship with a magpie that nested in a tree behind our house. He would sit on the fence alongside it and they would chatter together agreeably. The magpie would even come calling for him, waiting patiently in the garden until he came out. But does this affinity with humans and other creatures that magpies obviously have go any way to explaining my fascination with them?

“Other people have asked me that as well,” muses Andy. “I think it’s because they’re visibly interested in things. You can see the spark of intelligence there, and while some people assume it’s malice, I think some people correctly see a bright, thoughtful animal that can be communicated and reasoned with.”

But there’s another aspect to magpies as well, which is their place in folklore and superstition. For as long as I can recall, I have saluted a single magpie then loudly asked after its wife (without knowing its gender or sexual proclivities) and hoped that it has healthy chicks. Other people I know have similar reactions… David Lewis (@davidclewis) told me on Twitter that he grew up with his mother ritually greeting any magpie with “hello, sir or madam!” and his wife saluting them, which the “combined effects of this has led to me basing all important life decisions on their appearance or non-appearance”. Another says she had to forcibly stop herself from both pinching and slapping herself when she saw a lone magpie.

The superstition surrounding a single magpie stems from the folklorish rhyme, which we all know a version of – especially those who grew up in the 1970s and 1980s and remember the ITV children’s TV show Magpie, which had as its theme tune a variation of the rhyme.

The most common version goes like this: “One for sorrow, two for joy, three for a girl, four for a boy, five for silver, six for gold, seven for a secret, never to be told.”

Give yourself extra points if you know the rest of it: “Eight for a wish, nine for a kiss, ten for a bird you must not miss, eleven is worse, twelve for a dastardly curse.”

There are many other variations, some of them regional, and the rhyme was first recorded in 1780 in the book Observations on Popular Antiquities by John Brand. The folklorist and academic Dr Jacqueline Simpson collaborated with the late Terry Pratchett on the book The Folklore of Discworld when she met him at a book signing. The author was researching his next book and routinely asking people in the queue how many versions of the magpie rhyme they knew. Dr Simpson apparently replied: “About 19. Which one do you want?”, which led to the collaboration.

The magpie has generally been regarded as an uncanny bird. In Sweden it is connected with witchcraft, while in Devon it was customary to spit three times to avoid bad luck when a magpie was seen

I consulted my faithful folklore library for more information on why magpies are so entrenched in British Isles myth, legend and superstition. Brewer’s Myth and Legend, edited by J C Cooper, has an interesting note on the etymology of the name, suggesting it was originally “maggot-pie”, maggot being a corruption of Margaret – in the way that birds were often given human names such as Robin readbreast, Tom-tit, etc – and pie from pied, a nod to its black and white plumage.

“The magpie has generally been regarded as an uncanny bird,” notes Brewer’s. In Sweden, it says, it is connected with witchcraft, while in Devon it was customary to spit three times to avoid bad luck when a magpie was seen.

Magpies crop up in the Christian tradition quite extensively. It is said that the magpie was not allowed inside Noah’s Ark because of its incessant chattering, but instead had to perch on the roof.

And my copy of Zolar’s Encyclopedia of Signs, Omens and Superstitions suggests that the magpie has its black and white plumage because “unlike other birds, it never went into full mourning after Christ’s crucifixion. A Christian tradition in France says that magpies actually pricked Christ’s feet with thorns while he was on the cross; the swallows tried to pull them out, causing their breasts to be blood red. As a result, magpies were condemned to nest in tall trees while the swallows could find easy shelter under the eaves of houses.”

In The Element Encyclopedia of Magical Creatures, by John and Caitlin Matthews, it is said that in medieval bestiaries the magpie was seen as a symbol of the devil, and represented “the unseemly chatter of those who do not pay attention in church”, while its black and white feathers are a sign of vanity. Zolar says that the magpie is believed to have “a drop of Satan’s blood on its tongue. Tradition holds that it can acquire human speech, if its tongue is scratched and a drop of human blood is inserted therein.”

In Germany, a magpie calling near a house was a portent of death, as is a magpie preceding a person into church. In Yorkshire, magpies congregating on a dead branch is a sign of rain. But if the magpie merely chatters rather than calls, then it is simply heralding the arrival of a guest.

While the magpie is an often ominous symbol in Britain and Europe, in China and the East it is a very different affair, where the bird is considered to bring joy and good luck. The Qixi (also Qiqiao) Festival, which this year falls on 25 August, is a Chinese event also known as the Magpie Festival. It is built around a folk-tale about two lovers, a cowherd and a weaver girl, whose love was banned and the pair were banished to opposite banks of a river.

Every year, on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, a parliament of magpies would form a bridge over the river so the star-crossed lovers could meet.The Qixi (also Qiqiao) Festival, which this year falls on 25 August, is a Chinese event also known as the Magpie Festival. It is built around a folktale about two lover

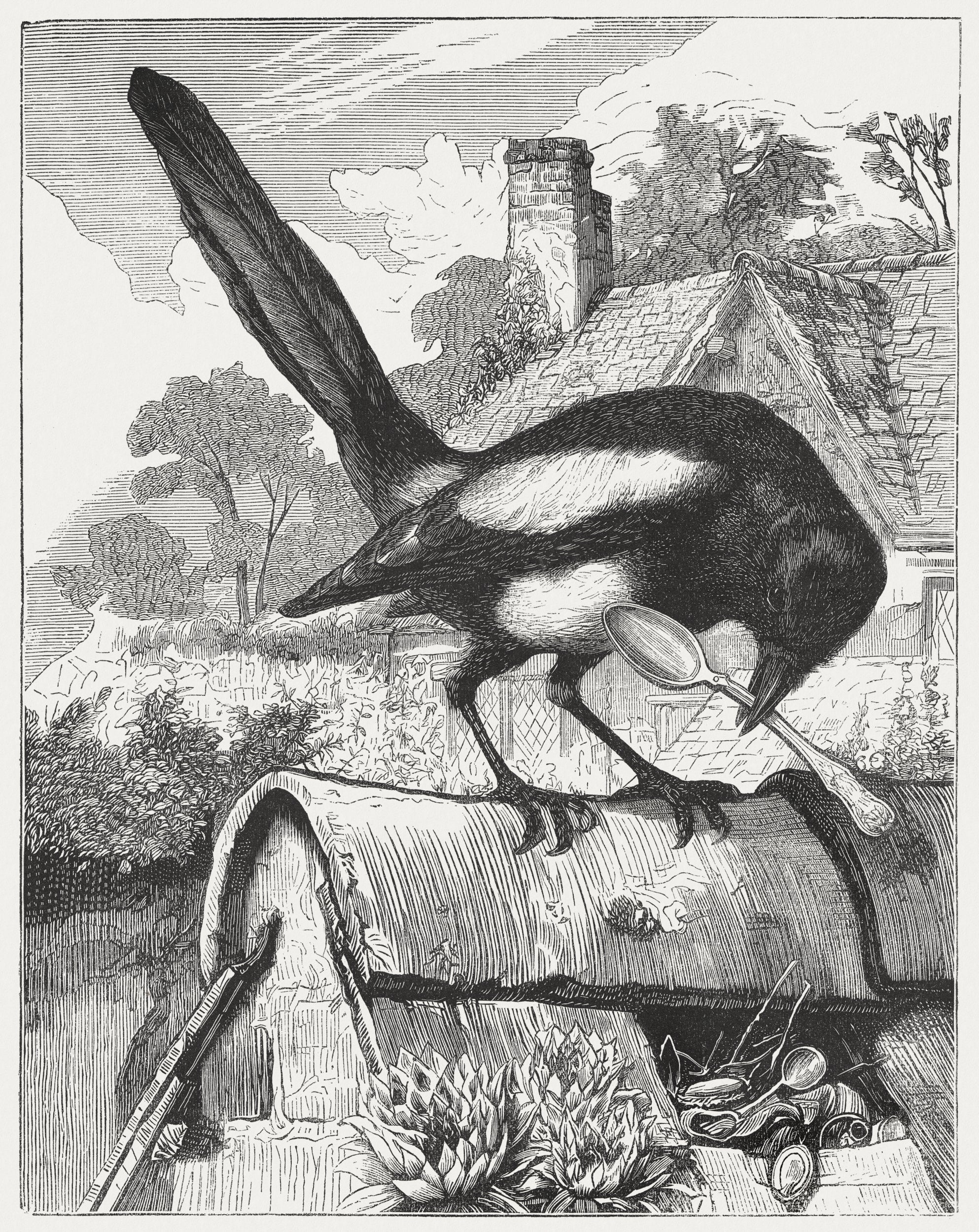

The magpie is an aficionado of shiny things, and will steal and hoard them – so much so that any human who exhibits the same love of gold or silver and shiny trinkets will be dubbed a magpie. That might also be an unfairness on the bird; we might have picked that up from the opera La Gazza Ladra by Giannetto De Rossi – aka The Thieving Magpie, which is built around the theft of a silver spoon by a swooping magpie. Magpies, along with their corvid family, do get a bad press. Not just in folklore and superstition, but in more pragmatic ways.

Mark Cocker is a British author and naturalist who has written extensively on corvids, especially in his 2007 book Crow Country, Birds Britannica (with Richard Mabey) and his current volume, A Claxton Diary. “There’s a lot of folklore attached to magpies and a lot of that is to do with the fact they’re black and white,” says Mark. “They seem to combine opposing moral qualities, and the rhyme that everyone knows alternates between bad and good luck… one for sorrow, two for joy, the kind of binary rhyming couplet that reflects our attitudes.

“In Western thought anything black was seen as evil so corvids especially have been painted with a lot of negative responses by people for thousands of years. Magpies are party to that negative trend in our attitudes, which are rooted in prejudice and have very little substantial evidence behind them.”

Aside from the bad omens associated with magpies – or perhaps that’s a deep-rooted if unacknowledged reason for it – people have a bit of a beef with magpies and their corvid cousins: ravens, crows, rooks, jackdaws and jays. They are generally believed to kill livestock on farms and because corvid numbers are increasing and songbird populations on the wane in Britain, many people have drawn conclusions from that.

Corvids can be pretty vicious with their prey. There is evidence that crows and ravens will kill young lambs, but there’s also strong evidence that the lambs they take were already doomed to die

“People have put two and two together and made five,” says Mark. “There’s very little evidence that corvids are behind the songbird decline. The real reason is our agricultural practices, but we need a scapegoat and blame the corvids.”

That said, Mark acknowledges that corvids can be pretty vicious with their prey. “There is evidence, for instance, that crows and ravens will kill young lambs, but there’s also strong evidence that the lambs they take were already doomed to die anyway, so they’re not as vicious and predatory as we imagine. And we have some of that prejudice towards magpies as well. But we are also now recognising that corvids are highly intelligent – perhaps equal to very young children or primates.”

Mark has also delved deeply into the folklore surrounding magpies, especially in the book Birds Britannica. He says: “It’s hard to find anything consistent in folkore, it’s always a blend of irrational, illogical associations. For that book I found some extraordinary stories of people’s fear of seeing one bird, and the sometimes ridiculous rituals they go through. I use my own brother’s family as an example, they have all these little sayings when they want to ward off the bad luck associated with magpies.”

Intelligence aside, it seems my mild obsession with magpies still doesn’t have much logic to it. That said, says Mark, even though they’re not particularly well-loved in farming communities, they do have their fans.

“Some people just love them,” he says. “They love them for their resilience, for the fact that they are persecuted, and they like them because they’re the underdog. And let’s face it, they’re incredibly beautiful birds. They’re not black and white at all, they’ve got lots of rich colours, particularly a sort of rich, sky-blue right through to turquoise and iridescent colours in that black plumage and then those lovely areas of white. They’re very characterful and they’ve got lots of personality.

“They’re alert to opportunities: one of the things that we can say is that in our decimated landscape much reduced by human activity, corvids are highly successful and one of the few groups of birds to buck the trend and actually increase. They are able to adapt to the reduced landscape we have created. So, love them or hate them, they’re fantastic survivors.”

All of which perhaps goes some way to explaining my fascination with this most beautiful, mischievous, intelligent and magical of birds. And it also shows me I’m not alone in that. I took to Twitter to ask if anyone else had any magpie tales or affinities. I wasn't disappointed.

Gareth A Hopkins (@grthink) commented: “Like a bunch of people here, I always nod and say 'Good Morning, Mr Magpie'. The morning before my son was born I saw four of them stood in a row on the path I took to get to the train, and took that as a good omen.” Four magpies, of course, being “for a boy” according to the rhyme.

Folkorist, author and comic book writer John Reppion (@johnreppion) offered some magpie legends, including one about how they were a favourite disguise of witches, according to Norse myth. He also has a magpie tattoo on his arm.

Some had more ominous tales, such as Natalie Persoglio (@natpersoglio) who said: “Portentous of looming death. One of my Welsh writing retreats has a magpie that knocks on the window with its beak each morning. When I read the visitors’ comments book, the magpie was mentioned many times over the previous years.”

And, of course, not everyone is a fan. Michael Mazenko (@mmazenko) says: “Magpies are miserable annoying screechy bullies of the bird world who move in packs like trashy mongrel hounds or hyenas. Helplessly watched them kill a whole nest of ducklings in a courtyard. They are low-down no-good shit-trash who are strangely protected as migratory birds.”

I am indebted to Chris Woodyard (@hauntedohiobook), author of The Victorian Book of the Dead, who furnished me with many fascinating facts, including an extract from a piece written by a “Mrs B” in a 1921 edition of the Living Age magazine, in which she expresses her “horror of a single magpie”, having had one tapping at her grandfather’s window during his prolonged death.

He also sent a letter published in the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research in 1905, detailing the terror a maid living in a remote cottage on the edge of Dartmoor was put through by repeated attempts to break into her room, which turned out to be a magpie rapping on her window every night.

But I’ll leave you with this heartwarming little tale about the magpie’s proclivity for shiny things, from Joanne Louise (@joeaton71): “I once found a diamond ring outside my back door, on the rim of a pot. I tried for ages to find out who it belonged to, to no avail but had a resident pack of magpies and assumed they had stolen it and dropped it somehow. My brother told me he had proposed to his girlfriend and so I gave it to him, they’ve been married 20 years and she still wears it!”

So if you see a lone magpie today, just ask after its wife, and all will be well. And see five or six together, and who knows? Maybe a bit of good fortune is coming your way…

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments