As we celebrate LGBT+ rights, we must reflect on the heroes who paved the way

They’ve been beaten, imprisoned and erased. Now that the UK is putting LGBT+ persecution behind it, we can forgive the past, says Jonathan Cooper, as long as we don’t forget it

Persecution. It’s obvious what it is. We all know when someone’s being persecuted. The state or others in power deliberately home in on a person or group of people and make their lives unbearable, unliveable even. At school, we call it bullying. In international law, we call those that are persecuted refugees.

Throughout the 20th century, the British state went out of its way to persecute its gay and lesbian community. The existence of a gay or lesbian identity was denied. Crimes that only gay men could commit were created. The gay and lesbian community was censored. There was institutionalised homophobia. Laws were there to be used against gay and lesbian people.

Mothers who were lesbian were “a risk”. Gay fathers were inconceivable. It was state policy for parents to reject their gay and lesbian children. Violence against gay men and lesbians was met with impunity. Fear of the homosexual was mitigation for causing harm to gay and lesbian people. It could even be put forward as a defence for murder.

As with all persecuted people, we gays and lesbians endured our exclusion. We put up with hate. When we acknowledge our identity, we do so alone. We join a rich and extraordinary history, but we reinvent ourselves as gay or lesbian. Many persecuted peoples have coping mechanisms and traditions to fall back on, taught to them by their parents and their parents before them. Gay and lesbian people do not have that connection with their persecuted selves. When we first come out, we’re on our own.

Lesbians were spared the criminal law, but at a price. Lesbians were erased. Any attempt to assert lesbian identity was met with outrage. In fact, the lengths taken to deny their existence bordered on absurd. Virginia Woolf’s relationship with Vita Sackville West, for example, was flatly denied, despite the fact that their intimacy was clear as a bell. Woolf, the finest English language writer, would be sidelined. Better to ignore that extraordinary prose if to be immersed in it might lead to some acknowledgement of Woolf’s sexual identity. Radclyffe Hall’s lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness would be banned with the approval of the courts.

As recently as 1970, lesbians as sexual beings continued to be airbrushed out. That poignant and tragic film, The Killing of Sister George was rated X, the most restrictive certificate at the time. Only the determined would get to see it.

Gay men were criminalised. Distinct from lesbians, we were given an identity, but only as depraved sexual beings. Even behind the neutered face of acceptable homosexuality (which had emerged by the 1970s, with people like Mr Humphries in the BBC’s top-rated sitcom Are You Being Served) lurked a “predatory queer”.

Many persecuted peoples have coping mechanisms and traditions to fall back on, taught to them by their parents and their parents before them. Gay and lesbian people do not have that connection with their persecuted selves. When we first come out, we’re on our own

Unlike our lesbian sisters, the story of male homosexuality is celebrated. We were saved by parliament in 1967 when they graciously decriminalised homosexuality and everything has been hunky-dory ever since. This convenient narrative overlooks the fact that the change in the law was only partial decriminalisation and that parliament were the ones that had criminalised us in the first place. The laws outlawing homosexuality remained on the statute book.

After 1967, when gay men had sex, we could now have a defence. Sex between men would not be a crime if there were only two of them, and both were over 21 years old. And the act took place in private. Where were these men to find somewhere private? If one of you was 20, you both faced conviction.

After 1967, up and down the country arrests of gay men for consensual sex increased. Can the state be spiteful? The treatment of gay men in the Seventies and Eighties suggests the authorities relished playing cat and mouse with queers. A tender kiss was enough to land you in the dock, if not the clink. A furtive glance could have you arrested for soliciting. Thousands of men were enticed by plainclothes policemen into believing that they were desired only for them to be nabbed.

Not content with individual arrests, the great British state in the 1970s went after cultural and artistic expressions of gay identity. The nastiest and most vindictive anti-gay cases were brought, the aim being to silence the queers. They even raided bookshops. Books from Gay’s the Word bookshop were seized. Have you been? Gay’s the Word is as dissolute as the Sistine Chapel.

February is LGBT History Month, an opportunity to reflect. This month two men are much in my thoughts. The gay brother of a friend who disappeared 60 years ago in his early twenties. Rejected by his family, including (to his now shame) his own brother, this gay young man walked away and has not been heard from since. The other is Uncle Neville, great-uncle of a friend of mine. It was whispered that Neville was gay, but he didn’t share his gay life with his family. My friend was informed just before Christmas that Uncle Neville had died a few weeks earlier. These men’s stories are lost to their families, which in turn diminishes their family histories.

As part of LGBT History Month, later today, Helena Kennedy QC and Geoffrey Robertson QC will discuss how criminal law continued to be used against gay men throughout the Seventies and Eighties: that period from partial decriminalisation in 1967 to Section 28 in 1988, which used civil law to denigrate homosexuality. Kennedy learnt her craft at the criminal bar defending gay men who were being prosecuted for consensual sex with other men. Her stories of defendants being dragged through the courts are heartbreaking. For these men, their only blessing was Kennedy. She at least would guarantee their dignity as the state sought to humiliate them.

We believe that LGBT+ persecution is firmly behind us now in the UK, but that doesn’t mean that it is forgotten or that the harm it caused doesn’t continue to linger

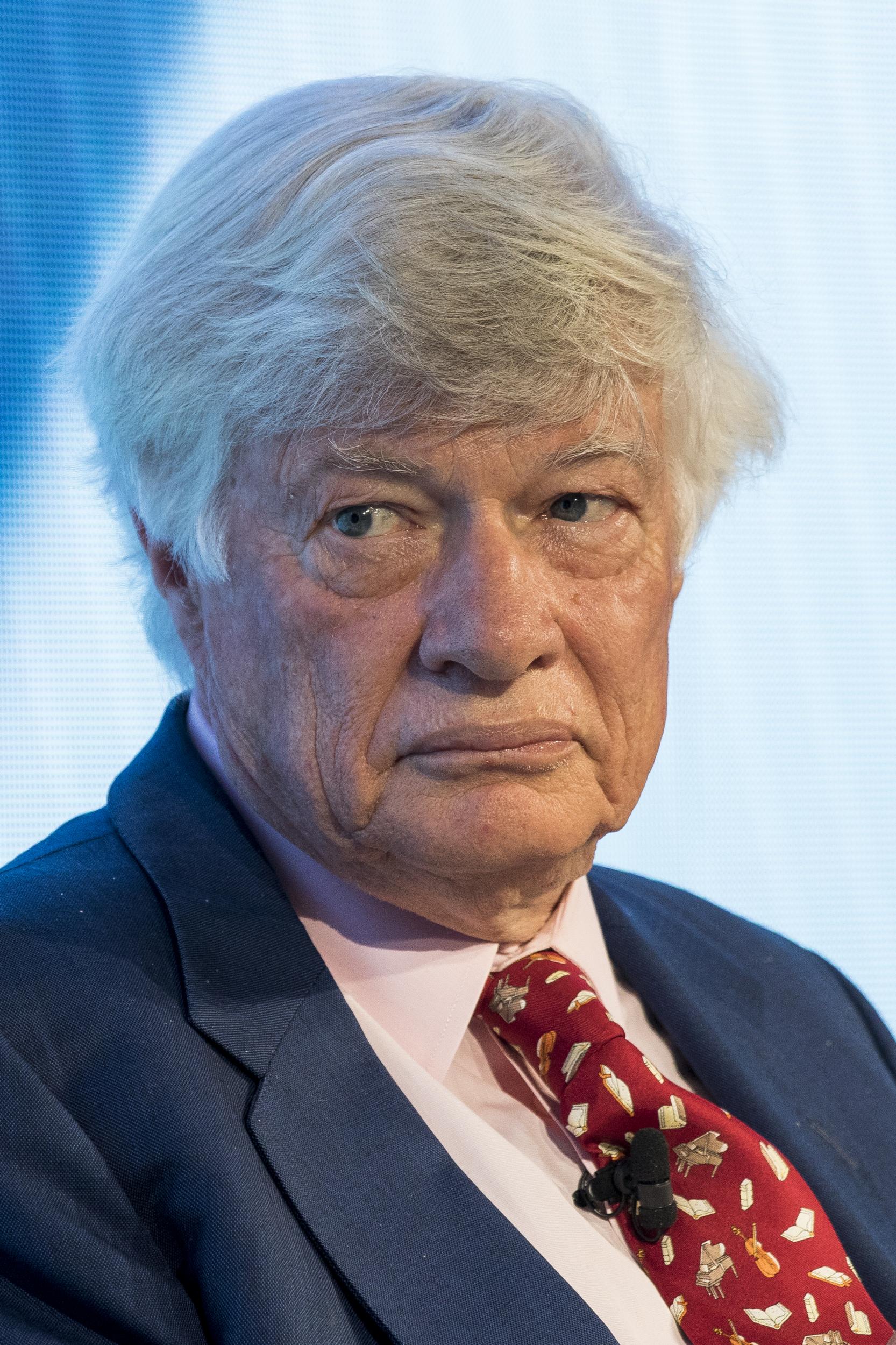

Geoffrey Robertson, the godfather of gay liberation in the UK, was involved in the key anti-gay cases of the Seventies and Eighties. Often hiding behind the apron of Mary Whitehouse, self-appointed custodian of the nation’s morals, the British state would back censorship cases being brought against gay men. It was a hard battle, and not all cases were won, but Robertson eventually shredded the state’s archaic censorship laws as they applied to LGBT+ people. He fought the law and he won. Robertson was the nemesis of Mary Whitehouse. He helped dismantle the tools of policing that kept LGBT+ people living in fear.

There are other speakers. Peter Tatchell will be there and Roz Kaveney too, but this is an opportunity to celebrate those straight people that resolutely stood by the persecuted gay and lesbian community. Kennedy and Robertson recognised the extent of gay and lesbian persecution in the UK throughout the 1970s and 1980s and sought to do something about it. The question that doesn’t get asked is, why didn’t others? In the war against queers, Robertson and Kennedy, if asked, can tell what they did during that war. They did not turn a blind eye, become complicit or help foment hate. They went into battle.

Millions and millions of others chose to maintain the status quo. These aren’t the people who bashed, arrested, went out of their way to cause harm or took away rights. They would note, but skim over, the crime reports of gay men who had been prosecuted in their local paper. They would feel uneasy about homosexual staff in schools. They would enjoy the stereotyping of poofs, queers and lezzers and would know they shouldn’t, but would join in with that banter. They would avoid homosexuals if they could. They would find homosexuality embarrassing and try not to find it distasteful. They would accept that gay and lesbian people were different and as such it was not inappropriate to treat them differently, however that manifested itself. And they would object to that handful of people, like Tatchell and Kaveney, who were just too strident. Why do they have to bang on about it? Why have they stolen our word, “gay”?

In 2010, the Supreme Court affirmed that to criminalise people because of their sexual orientation amounted to persecution for the purposes of refugee law. Gay men and lesbians cannot be expected to deny their sexuality and pretend to be straight. Did Lord Rodger create a new right? The right to go to “Kylie concerts” and drink “exotically coloured cocktails”? Does the Supreme Court decision mean that lesbians in Jamaica who are not criminalised but will be raped and murdered for being a lesbian cannot claim asylum? They too are, of course, persecuted.

And what of the situation in the UK for gay men and lesbians? Was that persecution? Prior to 1967, gay men without a doubt were persecuted whether or not they were convicted. As criminalisation continued post-1967, did persecution? Institutionalised homophobia remained into the 21st century as virtually all LGBT+ people will confirm. The criminal law may have been replaced in 1988 by the civil law in targeting gay and lesbian people but does that make it any less persecutory?

It’s hard not to draw the conclusion that the persecution of gay men and lesbians did not cease until 2000 with the entry into force of the Human Rights Act 1998. Even though the Conservative Party remained doggedly determined to retain an unequal age of consent and keep Section 28, by 2000 with a combination of EU law and the Human Rights Act, it’s probably correct to say that the persecutory legal system had been subsumed within a rights framework.

Where does this leave those that were persecuted and our persecutors? A proper independent inquiry needs to establish the scope and extent of LGBT+ persecution in the UK throughout the 20th century. This need not be a grand affair. A government-funded committee based at a university could do the job. Kennedy or Robertson (or both of them) would make admirable chairs. That committee would report to the prime minister. Part of its remit would be to assess the right to redress, to the extent that this is applicable and possible.

And what of the millions who were willingly complicit? Can we put their involvement down to different times? Persecution, surely, is persecution. And some, like Robertson and Kennedy, chose not to buy into the homophobic culture. Why didn’t everyone else? We need to establish a mechanism whereby people can apologise and be forgiven, should they wish to be.

Persecution destroys lives. Learning to live with it diminishes all of us. We believe that LGBT+ persecution is firmly behind us now in the UK, but that doesn’t mean that it is forgotten or that the harm it caused doesn’t continue to linger. We also need to be sure it doesn’t rear its ugly head again. Remedying the past is possible but only by acknowledging it. Uncle Neville’s stories will now never be heard. We’ll not know what happened to that young man who stepped out into the night in the 1950s, but we can still honour people like them. We can give visibility to all those who were erased. We can commemorate and celebrate. And we can say sorry.

Geoffrey Roberton, Helena Kennedy and others will be speaking at Policing Desire at Doughty Street Chambers tonight at 5.30pm. For more information, click here

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments