History suggests lefties have finally gained the upper hand

Ten per cent of the population are left-handed, but why is this – and how far back does left-handedness go? Sean Smith reports

If you’re one of the 700 million left-handed people, who gamely struggle with scissors, tin openers, corkscrews and Qwerty keyboards, you’ll have realised that the world is designed by and for right-handers. But take heart from the fact that there’s never been a better time to be a lefty, and it’s not just because banks are finally phasing out cheque books.

Although southpaws make up just 10 per cent of the population, five of the last eight American presidents signed their executive orders with their left hand. Leaning left is clearly no longer a barrier to professional advancement or social acceptance, but it hasn’t always been that way.

Lefties are a people without a backstory, because history has been written by a dominant right hand that hasn’t particularly cared for what its left has been doing. Surviving linguistic biases hint at the extent to which left-handed people have been marginalised. For example, the Latin word “sinister” merely meant “of the left side”, but over time left-handers were viewed with such suspicion that it gradually became synonymous with evil.

Yet, as far back as we can go into prehistory – according to the archaeological record at least – lefties have always been there, stubbornly making up a stable 10 per cent of the population, any time, any place, anywhere.

Studies that track how Neanderthals brought meat to their mouths by analysing marks on fossilised teeth suggest left-handers have been a 10 per cent constant in the hominid population for at least half a million years. An analysis of marks on 9,000-year-old tools found at an archaeological site in Belgium has corroborated that ratio, and a survey of 1,000 statues and illustrations dating back 3,000 years has estimated left-hand artistry at around the same level.

Human evolution’s steady maintenance of this small proportion of lefties over millennia suggests that left-handedness must have conferred evolutionary advantages.

Perhaps it’s best to start by considering why humans are such an unusually lopsided 90:10 species, when for most mammals and primates the “paw preference” ratio appears to be random, hovering at around 50:50. Even conflicting theories tend to converge around the evolution of the two characteristics that make us distinctly human: walking on our hind legs and talking.

As our brains became capable of managing a far wider range of tasks more efficiently and our fine motor skills developed, we became more successful as a species

At some point between 13 million and six million years ago, our species diverged from the common ancestry we share with chimpanzees. Our ancestors migrated from densely forested areas to the pan-flat east African plains, where rearing up on our hind legs and peering over long grass would make us both more likely to catch, and avoid becoming, prey.

By a process of natural selection, the ancestors who were better at standing were more likely to survive and pass on their genes. As we became hind-legged, and our hands became free, we became skilled foragers and later makers and users of tools.

Cognitive scientists believe that this hand-liberating transition to bipedalism sowed the seeds of our asymmetry as a species because it marked the moment when the left and right hemispheres of our brains started to specialise in different types of task. Divvying up cognitive roles to the different brain hemispheres is an energy-efficient division of cerebral labour known as lateralisation. We now know that lateralisation is common in animals, but to nowhere near the same extent as it is in bipeds, and particularly humans.

As our brains became capable of managing a far wider range of tasks more efficiently and our fine motor skills developed, we became more successful as a species. But it was our species’ later development of language that enabled us to inherit the earth.

Modern neuro-imaging confirms that, for most human beings, the left-handed hemisphere of our lateralised brains became home to our language-processing centre. As our left hemisphere evolved to produce and decode chatter, the criss-crossed engineering of our brains dragged right-handedness along with it as a side effect. This is because the left hemisphere controls what’s happening in our right-side limbs, and vice versa.

Right-handed dominance was a natural consequence of dominant left-hemisphere activity. Some cognitive scientists believe we unconsciously use right-hand gestures to illustrate the vocalised utterances that also emanate from the left-hand side of the brain.

When modern neuro-imaging revealed that left-hemisphere language processing is even more common in humans than right-handedness, and that 61 per cent of left-handers also process language in their left brain, perhaps the question that should have been asked is why only 90 per cent of us are right-handed.

Advocates of the “fighter hypothesis” believe left-handedness as a trait is likely to have survived at the constant rate of 10 per cent because the surprise element confers a competitive advantage in hand-to-hand combat. Lefties get plenty of practice against righties, but back in our hunter-gatherer past, a right-handed fighter’s first encounter with a southpaw opponent might very well have turned out to be also their last.

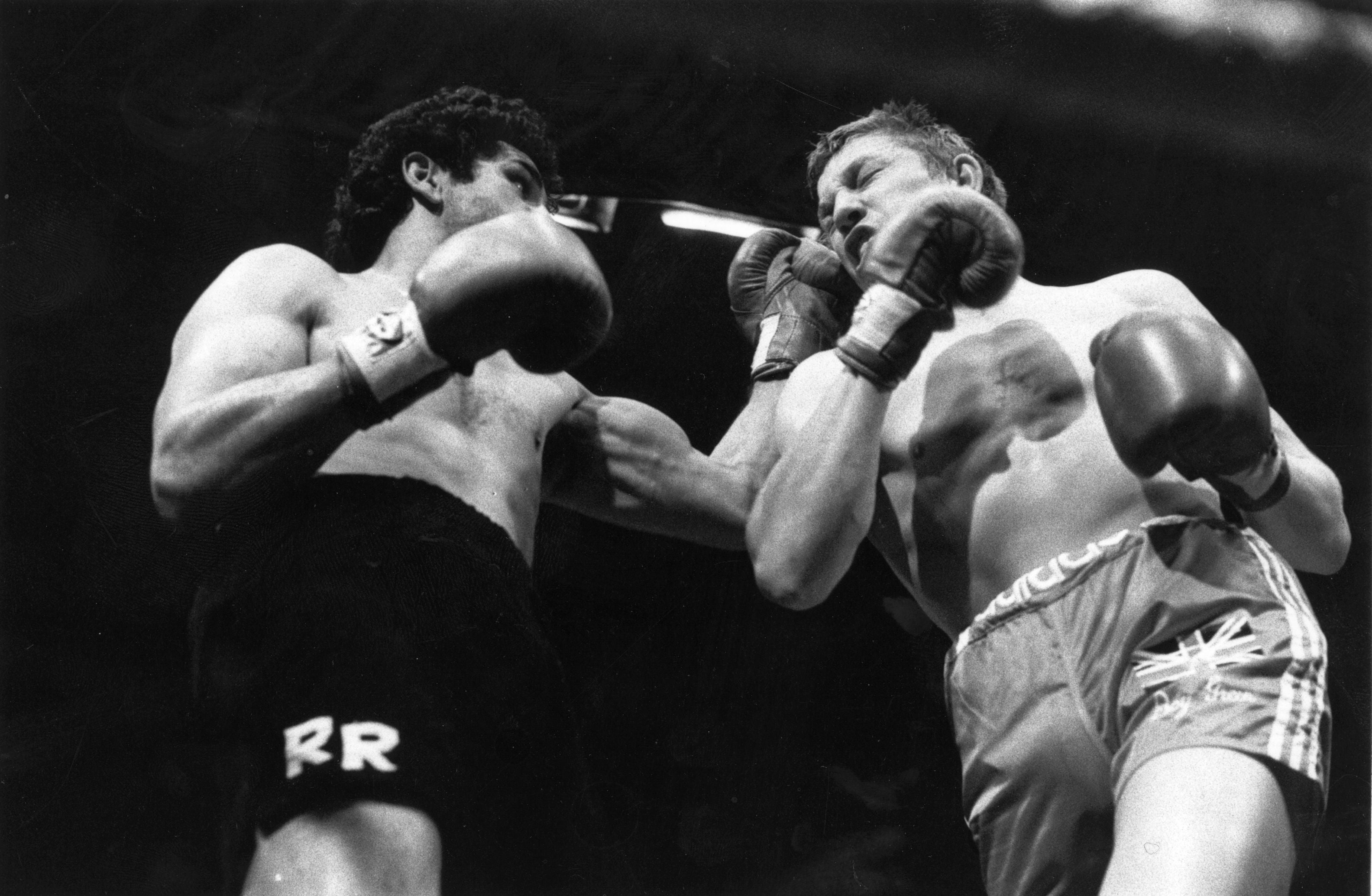

Evidence to support the hypothesis can be found in professional sports data today. According to a recent database of 10,000 boxers and martial arts fighters, southpaws recorded a significantly higher win percentage than their orthodox right-handed counterparts. Significantly, there is a slightly larger proportion of lefties in the few competitive hunter-gatherer societies that still exist today.

However, the fact that the proportion of lefties seems to have remained at just 10 per cent would suggest that the tribal communities of our hunter-gatherer ancestors were not all that “red in tooth and claw”.

In an evolutionary context, if those communities really were just driven purely by a bloodthirsty “survival of the fittest” mechanism, you would expect the handedness preference to equalise at around 50:50 over time until hand preference ceased conferring an advantage in combat.

Enclosed, superstitious communities with physical anomalies such as left-handedness were likely to stand out and attract unwelcome attention

A 2019 study used the stability of the 10 per cent figure to support the hypothesis that our successful survival as a hunter-gatherer species owed far more to language development and cooperation than to ruthless competition. The small but stable minority suggests an equilibrium, where the push-pull between the cooperative and competitive effects of handedness regulated itself at 10 per cent over time.

It’s likely that the history of left-handers started to take a sinister turn for the worse around 10,000 years ago, when our species transitioned from nomadic hunter-gathering tribes into settled farming communities. Early farming settlements may have been the cradle of modern civilisation as we know it, but enclosed, superstitious communities with physical anomalies such as left-handedness were likely to stand out and attract unwelcome attention.

Certainly by 500BC – if the Bible is anything to go by – the Judeo-Christian tradition seems to have regarded left-handers with righteous suspicion. In the old testament, the left side of the body is associated with deception or darkness. Satan sat on God’s left hand before his fall from grace. Eve tempted Adam after being crafted from his left rib. And in the new testament, the Christian tradition has always associated the left with underhand deception, immorality and illegitimacy.

In the parable of the sheep and goats, the righteous are on the right side and will be admitted to the kingdom of God; those on the left will be reunited with the devil. “Then shall he say also unto them on the left hand: ‘Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels’,” (Matthew 25:41).

The Romans believed that the left side was cursed, and after the fall of their empire the new Church of Rome installed that belief at the heart of Christendom.

The prejudice is still visible in superstitions to this day. When we throw spilt salt over our left shoulder we’re trying to blindside the devil and empower our guardian angel on the right. Getting out of bed on the wrong side is blamed for having a bad day; and illegitimate children, who were once considered not to be “part of God’s plan”, were said to have been fathered on the “wrong” (left) side of the bed.

The history of the English language is one of right-sided colonisation. The very word, “left”, is old English, and originally meant weak and broken. After the Norman invasion, French became the language of official public life. Their word for right (droit) also meant correct, and became synonymous with righteous authority, while the French word for left (gauche) became synonymous with unorthodox awkwardness and dubious legitimacy, much like its synonyms, maladroit and gawky.

To this day, in the political sphere, the right is associated with reassuring establishment orthodoxy, while the left is synonymous with unorthodox change and has a much harder job of establishing its legitimacy and right to govern.

In the middle ages, the Catholic Church believed left-handedness was a sign of the devil. The Spanish inquisition saw left-handedness as a deviation from Catholic orthodoxy and a sign of a heretical intent to overthrow the church hierarchy. During historical periods of “witchmania”, being left-handed could begin a process that might end with being burnt at the stake. Black magic is sometimes referred to as the “left hand path”.

Joan of Arc may or may not have been left-handed, but propagandist depictions that implied she was a witch certainly portrayed her that way. Significantly, in early productions of Macbeth, the “weird sisters” would have entered and exited stage left, and stirred their cauldron in a counter-clockwise direction. During the Salem witch trials, a woman who was left-handed was much more likely to be accused of being a witch.

Life might have been expected to improve for left-handers after the Enlightenment, but in socioeconomic terms, they would experience another sinister downturn in their fortunes. During the second industrial revolution of the Victorian era, left-handers were socially “outed” as a very visible minority for the first time.

In an era of statutory schooling, left-handedness was beaten out of children who tried to write with their left hand. Teachers presumably thought they were being cruel to be kind when they tied left hands to chairs to enforce right-handed use. The tendency was particularly pronounced in the Scottish and Irish school systems.

It’s thought that the two brain hemispheres are better connected in left-handed people, which may well confer an advantage in language use

King George VI’s lifelong stutter was depicted in the film The King’s Speech, and is believed to have been a manifestation of a “misplaced sinister” – a recognised psychological condition thought to be caused by forcing left-handed children to write with the “correct” hand.

Left-handed children who used their natural hand for writing had to push the steel nibs of ink pens against the grain of the page, which tended to produce smudged, poorly presented work, and were often assumed to be less academic.

Meanwhile, in the workplaces of the industrial revolution, left-handed factory workers also struggled to compete with their colleagues, because machinery and equipment was specifically designed for right-handed use.

In 2007, handedness researchers from University College London studied crowd scenes filmed by Victorian cinema pioneers Mitchell and Kenyon. By analysing handwaving, they were able to calculate that for those born between 1890 and 1910, the proportion of the population that was left-handed had fallen to an all-time low of just 4 per cent, in a phenomenon they referred to as the “Victorian dip”.

Within just a few generations, the hostile environment in schools and factories had depleted levels of left-handedness in the late Victorian gene pool because less successful lefties were marrying later and having fewer children. Left-handedness didn’t regain its natural rate of 10 per cent in England until halfway through the 20th century.

But a review of more modern history suggests that now it may be lefties who have gained the upper hand. The southpaw effect means that left-handers are over represented in professional competitive sports. If you’re a competitive parent with Olympic dreams for your left-handed children, you’d be well advised to direct them towards quickfire adversarial sports, such as tennis, cricket, boxing or baseball. Fifty per cent of top hitters in baseball history have been left-handed, despite letf-handers only making up 10 per cent of the work force.

Perhaps no one has done more to level the academic playing field for left-handers than Laszlo Biro, the inventor of the ballpoint pen. But neuro-imaging also suggests left-handers have brains that are organised in an unusual way that confers several other cognitive advantages. It’s thought that the two brain hemispheres are better connected in left-handed people, which may well confer an advantage in language use. According to researchers from the University of Toledo, it may also be the reason why left-handers have better memories.

In mathematics, left-handed students are known to have a significant edge. A study of 2,300 Italian students found that when it came to difficult problem solving, left-handed edged out their right-handed peers.

By having more balanced brains, with right hemispheres that more effectively process spatial awareness, left-handers are also over-represented in the architecture and design professions. Their ability to navigate the kind of spatial shape-orientation questions found on IQ tests is also likely to explain why lefties make up an impressive 20 per cent of Mensa’s membership.

If there were still a need for a left-handed liberation movement, it could select its leaders from a stellar cast of southpaw overachievers that includes Oprah Winfrey, Nancy Pelosi, Noam Chomsky, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, and Barack Obama.

Nowadays, claims about left-handers being more creative have taken on the status of urban myth. But even wildly unsubstantiated claims show just how far the pendulum has swung back to the left hand, almost as an act of reparation for the sins of the past.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments