Lata Brandisova: The fearless, forgotten hero who humiliated the Nazis on horseback

While women in sport continue to fight for equal opportunities and respect, Richard Askwith has unearthed the remarkable lost story of a pioneering woman jockey whose struggles and achievements on the eve of the Second World War feel uncomfortably relevant today

Does anyone really want to read a book about horse racing?” asked my Czech friend Anna, when I told her I was researching a biography of a forgotten jockey called Lata Brandisova. “Especially that sort of racing, where horses get hurt? Also,” she added, when I mentioned that my heroine had been a countess, “doesn’t everyone despise aristocrats these days?” These were valid objections. If it hadn’t seemed rude, I’d have mentioned another: English-speaking readers have little interest in stories involving Czechs.

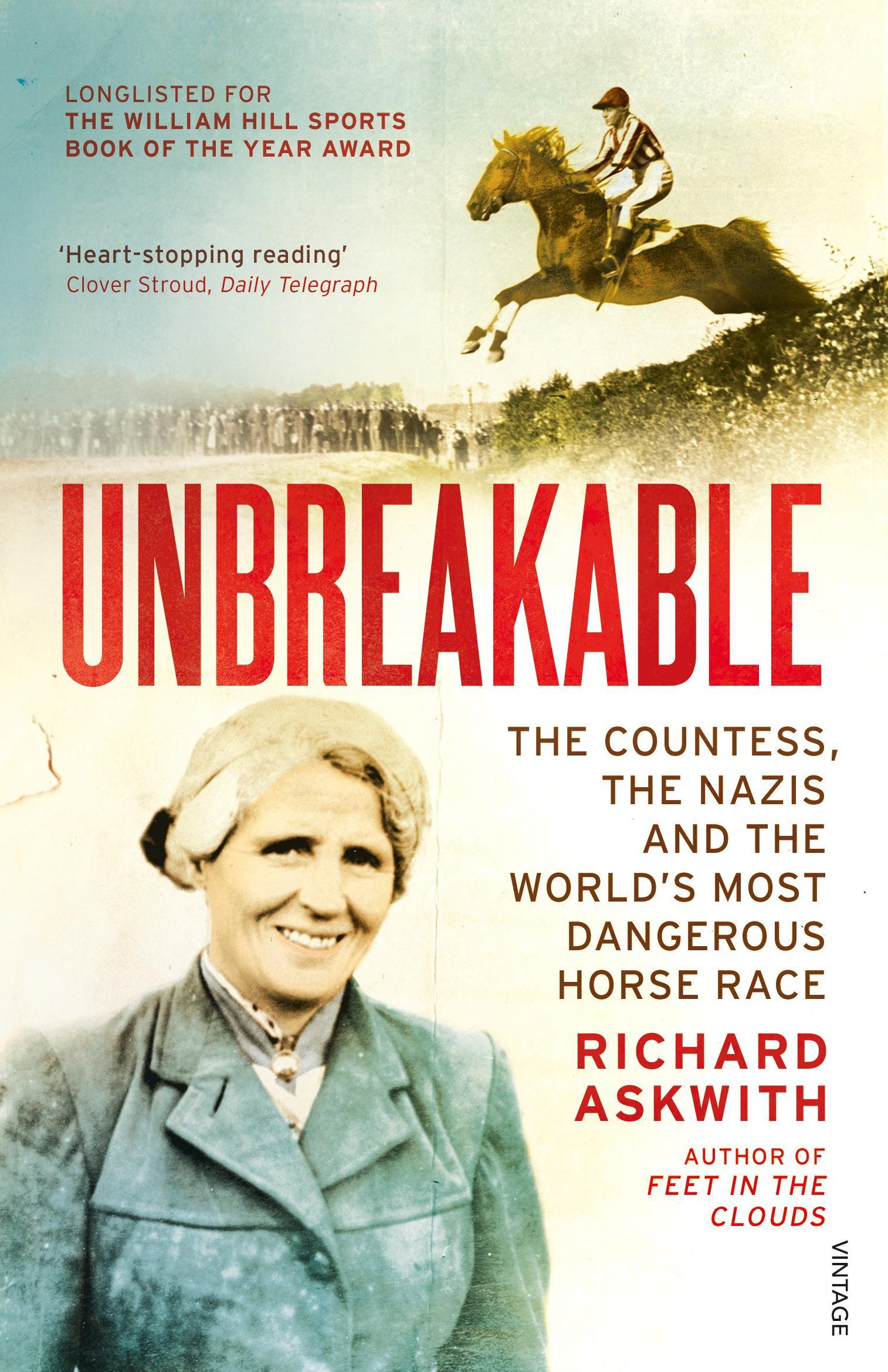

These issues had been bothering me for months. Ever since the project first occurred to me, I’d been trying to talk myself out of it. Where was the sense in labouring to piece together the lost story of a long-dead horsewoman no one had heard of, in a faraway country and an impenetrable language, when most people would take one look at my proposed subtitle – “The countess, the Nazis and the world’s most dangerous horse-race” – and decide that, on the whole, these were not themes they wished to read about?

I resolved several times to drop the idea. But the story wouldn’t drop me. Instead, it kept on demanding to be told. Eventually, I gave in.

It’s the tale of a strange, shy woman, born into privilege in 1895, who became an icon for her nation and her gender on the eve of the Second World War; fell foul of two different totalitarian regimes; became unmentionable; and died, forgotten and poor, in 1981.

Its sporting context is a notorious horse-race, the Grand Pardubice steeplechase, which is sometimes described as a more reckless version of the British Grand National. Its 31 life-threatening obstacles, including the monstrous Taxis ditch, are spread out along a course of four-and-a-bit miles, much of which is ploughed. It’s less extreme today than it was when Lata was riding. Even so, the risks to jockey and horse are obvious and severe.

Some consider merely riding in it a sign of insanity. Others question the ethics of exposing horses to its dangers – despite the enthusiasm with which horses generally seem to participate. I sympathise with such sentiments. Yet somehow they don’t detract from the value of Lata Brandisova’s achievements. That’s partly because, though she lived in an age less concerned with animal welfare than ours is, she herself was noted for her exceptionally gentle and sympathetic approach to the creatures she rode. Conventional wisdom held that riders must dominate their horses. Lata insisted that a horse would give of its best only if coaxed into being a “willing helper and friend”. Horses loved and trusted her, and I am not aware of any having come to harm in her care.

But even if extreme steeplechasing is not to your taste, there are other reasons for thinking that Lata’s achievements matter. One is their political and historical context, which is simultaneously distant and uncomfortably similar to our own. Born in what is now the Czech Republic in the twilight years of the Habsburg empire, Lata came of age just as the First World War was reducing the old aristocracy’s charmed world to rubble.

In the old world her gender had allowed her no prospect of riding competitively. Her job was to marry a fellow aristocrat and bear his children; that was all

A free, independent democracy emerged from the ruins in 1918: the First Czechoslovak Republic. Tomas Masaryk, its idealistic founder and first president, quickly introduced a radically progressive political agenda. Aristocratic titles were abolished. The ruling class’s bloated estates were gradually reduced. And equality between the sexes was enshrined in the constitution.

As a countess, Lata suffered from the first two measures (although by 1918 her family had already lost much of its land and wealth). The third promised opportunities that, if real, would more than compensate for the other losses. She had been riding since she was eight; her miraculous rapport with horses was obvious to all who saw her do so. In the old world, however, her gender had allowed her no prospect of riding competitively. Her job was to marry a fellow aristocrat and bear his children; that was all.

Sometimes, growing up, Lata and her sisters had organised horse races of their own. When they did so, they dressed up as men and painted moustaches on their faces. Back then, the idea of a female jockey had seemed absurd. Now, however, Lata began to dream.

In fact, despite the constitution’s promise of equal rights, old habits of prejudice and discrimination died hard. Women in European democracies were taking to sport with growing enthusiasm, but the men who ran horse racing showed little appetite for opening their world up to female competition. One leading Czechoslovak trainer recognised Lata’s ability and allowed her to exercise his horses. But for many years that was the only outlet permitted for her talents. Not until she was 32 was she allowed as far as the starting line of an official competitive race.

Her first race was a low-key affair: a four-horse race in which all the riders were women. It incurred the disapproval of the racing press but little else. Her second – the 1927 Grand Pardubice steeplechase – caused a scandal that echoed across Europe. The race, which attracted riders from many countries but was prized by Czechoslovaks as their own big national sporting event, had been designed as a preparation for war: its whole point was to be life-threatening.

If you were man enough to ride in it, you were man enough to die for your country. Even in the 1920s, most of the men who rode in it were cavalry officers. They refused point-blank to compete against a woman in such a perilous race, claiming that to do so would be an intolerable stain on their honour.

The liberal consensus that had given birth to Czechoslovakia seemed, by contrast, to be dissolving. People grew used to reports of hatred being whipped up against Jews, communists, trade unionists and freemasons

They were persuaded to back down only when the English Jockey Club intervened; and, even then, were still protesting on the day of the race. Lata joined them at the start in an atmosphere of furiously simmering hostility; faced them down; raced with them; fell five times; remounted five times; and, unlike eight of the 13 starters, finished.

Having proved both her durability and her courage, Lata was able to return to the race in subsequent years, gradually winning more respect and eventually being accepted as a kind of national treasure. Her results improved, but she could never do better than second. Eventually, in 1936, the owner she rode for lost faith in her and gave her regular ride to a man instead.

The world had changed again by then. Democracy and equal opportunity remained the (theoretical) guiding principles of Czechoslovak life. Across the border in Germany, however, the extreme conservatism of the far right had been flourishing. In 1933, Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, and those two tides converged, creating a whirlpool of ideological conflict that sucked in much of Europe.

The far right grew steadily stronger. The liberal consensus that had given birth to Czechoslovakia seemed, by contrast, to be dissolving. People grew used to reports of hatred being whipped up against Jews, communists, trade unionists and freemasons; and against “Amazons” – that is, women who followed traditionally masculine pursuits rather than staying at home to raise families. A woman’s role, asserted Hermann Goering in 1934, is to “take hold of the frying pan, dustpan and broom, and marry a man”. The same year, the Women’s World Games, first held in 1922, took place for the last time.

As the “low, dishonest decade” progressed, the battle for hearts and minds grew dirtier. The Nazis exploited the new medium of radio to disseminate propaganda and fake news. They also discovered the power of sport as an ideological weapon. The Berlin Olympic Games of 1936 are the most notorious example of a sporting event being used to promote the Third Reich’s warped ideals, but there were many others – especially in sports involving horses. And few arenas mattered more than the Grand Pardubice steeplechase, where the Nazis could not only present themselves as a master race of invincible Aryan warriors but also humiliate the neighbours whose land they coveted; neighbours they despised as (in Hitler’s words) “sub-human Slavs”.

Year after year, through the 1930s, German horses with German riders kept winning the Czechoslovaks’ celebrated steeplechase. More precisely: Nazis kept winning. The leading German jockeys were all officers in the Equestrian SS or, in a few cases, the Equestrian SA (the “Brownshirts”). Far from being reluctant representatives of Hitler who obeyed orders only out of fear, several were enthusiastic early adopters of the Nazi ideology. They actually wanted their victories to advance the Nazi cause.

The Czechoslovaks could muster only a few cavalry officers riding no-hopers – and one middle-aged woman: 42-year-old Lata Brandisova

The string of Nazi victories caused agonies to Czechoslovak patriots, and to anyone who didn’t enjoy seeing a liberal, progressive democracy being crushed by the poster-boys of fascism; but Himmler, Goebbels and the rest were delighted at triumphs which Das Schwarze Korps, the SS newspaper, hailed as evidence of “the new spirit of our nation”.

In the second half of the decade, the Third Reich began to seem unstoppable, in and out of the saddle. Calls for Czechoslovakia to be taken under German control grew louder and more aggressive. Then came 1937. That September, Tomas Masaryk died, provoking a vast national outpouring of grief and unity. It was one of those tidal waves of mourning that happen once or twice in a century; the kind we associate with figures like Churchill or Mandela. Two million people brought Prague to a standstill for the funeral of the “founder-liberator” who had embodied their Republic’s ideals. “That was not a crowd,” wrote one observer. “That was a nation.”

Less than three weeks later, it was time for the Grand Pardubice. Patriots and democrats flocked to Pardubice race-course in unprecedented numbers (the organisers stopped counting after 40,000) to see what the official programme dubbed “The battle of Pardubice”. The Germans had sent their strongest ever party of Nazi paramilitaries, including two Brownshirt officers and three from the SS. The Czechoslovaks could muster only a few cavalry officers riding no-hopers – and one middle-aged woman: 42-year-old Lata Brandisova, back from assumed retirement, a silver-haired countess riding a little golden mare called Norma.

To find out what happened next, you should probably read my book. (Or you can get a preview by reading the extract that The Independent will publish this Sunday.) But you’ve probably guessed that, one way or another, Lata must have done quite well. Otherwise, why write a book about her?

Yet that isn’t the whole story; or even, perhaps, its most remarkable feature. For a few months after the race, Lata Brandisova was the most famous woman in Czechoslovakia; the most famous sportswoman in Europe. She was interviewed, profiled, photographed, courted by the great and good. For her threatened nation, she was a figurehead from the same mould as Joan of Arc. Yet when I first tried to write about her, she was forgotten: even, with a few exceptions, among Czechs and race-goers. Her story had been relegated to a footnote in the annals of sport. Why? What happened?

The answer is: more history. The Grand Pardubice steeplechase of 1937 was the last for almost a decade. In 1938, the Munich Agreement led to Czechoslovakia’s dismemberment. Then, in 1939, came invasion and war. Lata’s was one of the first estates the Nazi occupiers seized. She had humiliated the Third Reich’s finest warrior-horseman, and her family had subsequently been associated with some defiantly pro-Czech public declarations. She had to be punished.

She endured the resulting hardship uncomplainingly and – while a Waffen-SS cavalry regiment based on the Equestrian SS was committing atrocities on horseback in the East – quietly did what she could to help the Czech resistance. In May 1945, she risked her life to tend the wounded during the fight to liberate Prague. In short, she had a good war.

She expected a good peace, too, but she was wrong. By 1945, memories of her 1937 triumph were already beginning to fade. Soon afterwards, the communists came to power: partially following the 1946 elections; totally following their 1948 coup d’état. Lata was identified as a class enemy. Her property, briefly restored when the Nazis were defeated, was once again taken away. She was evicted from her home, which was looted, and never saw it again. Instead, for nearly 30 years, she and two sisters lived in poverty and obscurity in a tiny cottage in the woods, without electricity or running water.

The race that was designed as the ultimate test of manhood has been welcoming female jockeys for more than 80 years

She died forgotten. Eight years later, the Iron Curtain fell, and the achievements of people like Lata could safely be celebrated again. By then, however, a new generation of race-goers had grown up who had never heard of her. To most intents and purposes, her story remained lost. Had I not written Unbreakable, it would still be lost today.

Yet in one crucial respect, Lata’s legacy survived. The taboo she broke in 1927 remained broken. Women have continued to ride in the Grand Pardubice: not every year, but often enough for their participation to seem unremarkable. The race that was designed as the ultimate test of manhood has been welcoming female jockeys for more than 80 years.

The rest of the racing world, shamefully, has been slow to catch up. The Grand National got its first female jockey in 1977 – 50 years later than Pardubice. Charlotte Brew, the woman in question, was horribly abused for her achievement – and much preferred the reception she received when, later that year, she become the first Englishwoman to ride in the Grand Pardubice.

In recent years, women steeplechasers have been making more of an impact, in the UK and beyond. If you follow National Hunt racing, you’ll recognise such names as Bryony Frost, Harriet Tucker, Nina Carberry, Rachael Blackmore, Lizzie Kelly, Katie Walsh. Their successes shouldn’t surprise us: a major study published by the University of Liverpool in 2018 demonstrated fairly conclusively that, once the quality of the horses is taken into account, gender has no bearing on the outcome of a race.

Yet the same study showed how steeply the turf is sloped to men’s advantage. Women account for 74 per cent of people who ride horses, 51 per cent of stable staff, 11.3 per cent of professional jockey licences and 5.2 per cent of actual rides in races.

The achievements of women like Frost and Tucker shouldn’t blind us to the fact that, in horse-racing as in other sports, we remain a long way from anything approaching true gender equality. And there are still plenty of people in racing who insist, publicly or privately, that female jockeys aren’t tough enough to handle the most extreme steeplechases. The story of Lata Brandisova disproves that theory conclusively – or would do, if anyone in the sport were aware of it.

Perhaps, next month, a woman will ride the winner of the Grand National for the first time. I hope so. (My money’s on Bryony Frost on Yala Enki, if they run; but Rachael Blackmore and Lizzie Kelly may well be in with a chance as well.) What I hope even more, however, is that this will be the year when Lata Brandisova gets the recognition she deserves.

She wasn’t the type to seek the limelight. She preferred the quiet company of horses to the whirl of fame. Yet her shyness hid a quiet courage that shrugged off the constraints of prejudice and danger. She became a symbol of hope and freedom in her nation’s darkest hour, and her achievements made a lasting difference to the opportunities available to the women who came after her.

Female high achievers often get a raw deal from history, especially in sport. Few have got such a bad deal as the woman who defied the warrior-athletes of the Third Reich in the world’s most dangerous steeplechase.

‘Unbreakable: The Countess, The Nazis and the World’s Most Dangerous Horse Race’, by Richard Askwith, is out in paperback by Vintage (£9.99). To purchase any UK edition of the book, click here. American readers can order the US edition here.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments