Twenty years after the end of the war, the Kosovo Museum is leading the fight for independence

An exhibition highlighting Kosovo’s plight to become a state shows that not all political battles are fought by diplomats behind closed doors. Luke Bacigalupo and George Kyris investigate

This year marks two decades since the end of the last war in the Balkans. During the break-up of Yugoslavia, efforts by the Serb leader Slobodan Milosevic to limit the autonomy of Kosovo’s Albanians led to war and an attempt at independence. The war ended with Nato intervention in June 1999, which secured Serbia’s departure from Kosovo and allowed the international community to help rebuild it after the conflict, pending an agreement on its final status.

In 2007, the UN proposed that Kosovo become an independent state under international supervision. The proposal was rejected by Serbia, but Kosovo implemented parts of the UN plan and declared its independence in 2008.

Kosovo closely resembles the process through which states have been born in recent times, usually by separating from another state. This is, for example, how South Sudan was born – by separating itself from Sudan in 2011. But while carving out a territory that you can control and govern is important, being recognised as the sovereign of this area is also crucial to functioning like other states.

The value of recognition by other states is evident in how recent attempts at independence have been treated: South Sudan is considered by many to be the youngest state in the world, because it is the latest state accepted in the UN. Other declarations of independence since then, such as that of Donetsk and Lugansk in eastern Ukraine in 2014 or Catalonia in 2017 have been ignored internationally and so are not considered to have resulted in new states.

Eleven years after its declaration of independence, Kosovo has a functional government and appears to be like any other state, including in international relations. For example, Kosovo is part of the World Bank and the IMF. In sport, Kosovo is a full member of Fifa and Uefa and its football team is on track to qualify for the next European Championship. Meanwhile, Tokyo 2020 will be Kosovo’s second appearance at the summer Olympics.

It might come as a surprise, then, that Kosovo’s declaration of independence in 2008 is not recognised by almost half of the UN’s members, including China and Russia, which are on the UN Security Council. Until these two states change their stance and stop vetoing Kosovo’s membership, a seat at the UN is simply impossible for Kosovo.

Kosovo is not the only state that has only one foot in the global order. Palestine is in a similar state of limbo, left outside the UN despite being recognised by the majority of the members, as well as being part of other international organisations like the Arab League. Taiwan is also not fully recognised, despite being one of the world’s leading economies.

Kosovo has also had to face a recent trend of smaller states withdrawing their recognition, following an orchestrated effort by Serbia, which still refuses to recognise its former province as an independent state. There was a brief diplomatic crisis recently when the Czech president suggested that his country might do the same. Serbia has also successfully lobbied against Kosovo’s membership of Unesco and Interpol.

This tactic is being used by several states that see independence movements as undermining their sovereignty. China has used its diplomatic clout to convince states to de-recognise Taiwan. Morocco makes trade deals with other states on the condition they de-recognise the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic in Western Sahara, which Morocco considers as part of its territory.

The division of the international community on issues of recognition means that the journey of Kosovo, Palestine and others to fully recognised statehood is incomplete. Palestinians and Kosovars are just some of the people still in the process of trying to convince the world that their country is a state and deserves independence. Naturally, persuasion is mostly pursued through diplomacy. For example, political allies of Kosovo drew attention to the smooth running of the recent elections as a sign of a properly working democracy. But a less examined, and in some respects more interesting way in which this is done is through culture. Specifically, the Kosovo Museum in Pristina shows how museums can be used to promote the image of a newborn state and push for its international acceptance.

Located in the capital city of Pristina, the Kosovo Museum is at the forefront of developing a cultural expression of Kosovo’s statehood. The ground floor displays a selection of archaeological items from prehistoric times to the medieval period. This floor is labelled Ancient Dardania, a Roman province that covers most of what is now modern Kosovo. It gained importance during the struggle for independence in the 1990s when it was used to emphasise Kosovars’ ancient heritage, and featured on a new Kosovar flag emblazoned across the two-headed eagle of the Albanian flag. The use of the name Dardania is also a nod towards Albanian nationalist historiography, which claims that Albanians are the original pre-Roman inhabitants of much of the Balkans. This contested interpretation of ancient history has been used as a justification for modern-day Kosovo’s efforts to break free from Serbia, on the basis that the Serbs are usurpers who have taken ownership of land from its original inhabitants.

This use of history to support modern political positions is mirrored in the National Museum in Serbia, which offers an opposite portrayal of Kosovo, as Serbian lands ruled by Serbian kings in the Middle Ages. After renovation, the museum re-opened in 2018 on the anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo. This battle is often interpreted in Serbia as a great defeat by the Ottoman army and the beginning of the subjugation of the Serbs by the Ottomans. The contrast between the two museums and their interpretation of the same territory demonstrates how the struggle over Kosovo’s recognition is fought not only in the present, but backwards through history and culture.

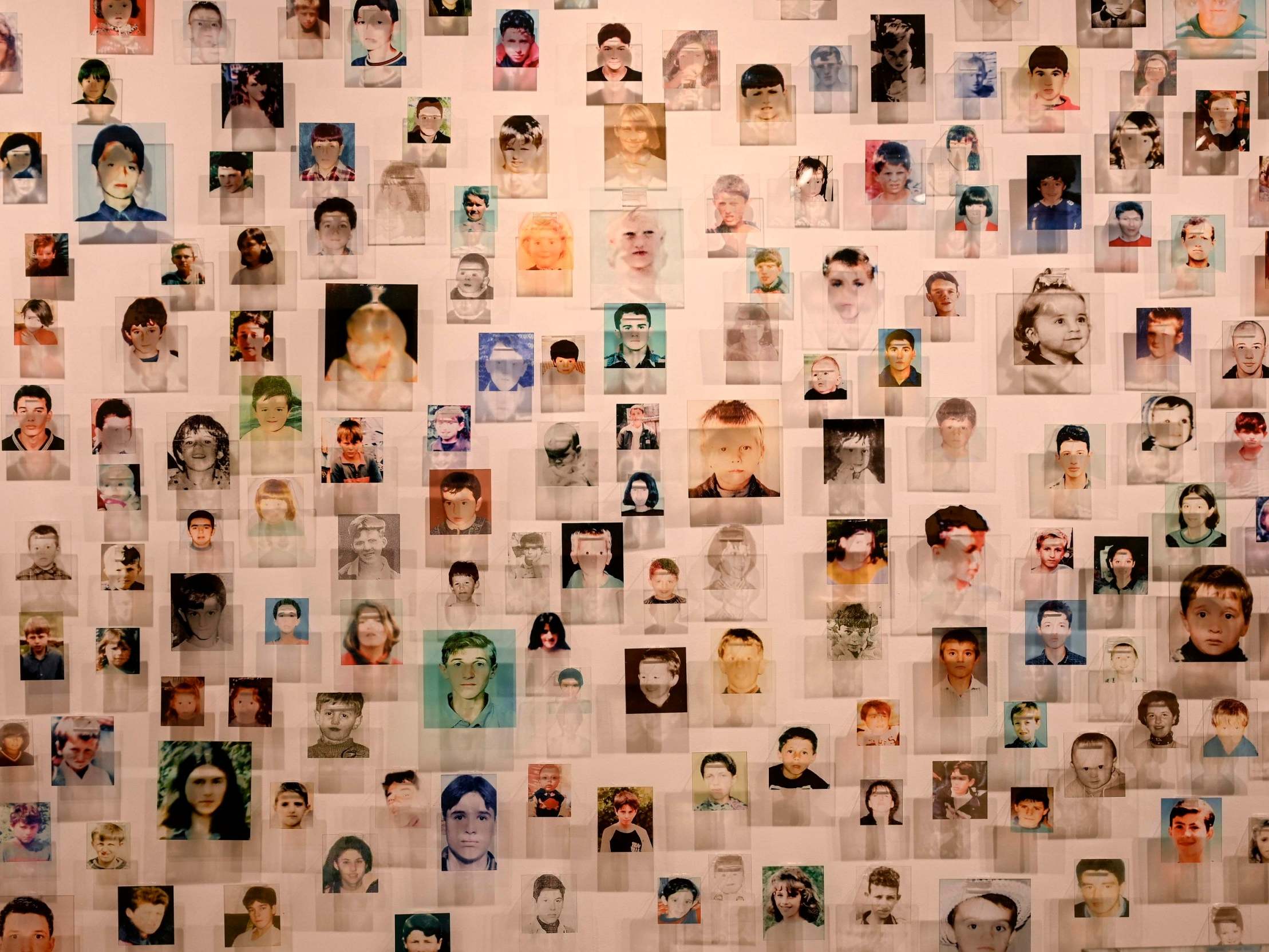

Back in Pristina, the vast majority of the exhibits on the second floor are dedicated to the past 30 years, during which time Kosovo fought for its independence from Serbia and began to organise itself as a separate state with the help of the UN, the EU, and especially the United States. Visitors can see the uniforms of Kosovo Liberation Army fighters from the 1990s and the motorbike of Adem Jashari, a famous guerrilla fighter killed by Serb police. Shells used during the Nato bombing of Yugoslavia sit alongside a cowboy hat belonging to Madeleine Albright, the former US secretary of state and one of Kosovo’s warmest supporters in the fight against Serbia. Another display is dedicated to Ibrahim Rugova, at one time referred to as Kosovo’s Gandhi because of his advocacy for independence through non-violent resistance to Serbian rule.

These artefacts of armed and diplomatic struggle sit alongside exhibits that aim to convince the visitor that Kosovo is an equal member of the international community. These include photos of meetings of Kosovar and foreign diplomats and a display of Kosovo’s stamps, including designs that celebrate Kosovo’s independence, its acceptance as a Uefa member and its first ever participation in Olympic Games in Rio in 2016. The fight for independence and recognition culminates in the museum’s most imposing room, which displays a golden plaque engraved with the 2008 Declaration of Independence, surrounded by an array of flags of the states that have recognised Kosovo.

While we often think of museums as neutral, objective institutions that are beyond politics, this impression could not be further from the truth. Many museums do not have a clear and obvious political agenda, as Kosovo’s museum does, but all museums are by their nature political. History museums that are designated as “national” museums are often even more explicitly political than others. This is not new. Many national museums in Europe were founded in the 19th century to establish the existence of a distinct people in order to justify the nation state. Examples include the Hungarian National Museum founded in 1802, the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremburg established in 1852, and the National Historical Museum in Athens founded in 1882. They have often been characterised as temples or shrines to the nation that reproduce the mythologies and uncritical historical narratives that underpin specific national identities.

The Kosovo Museum is in some ways a 21st-century version of this kind of national museum. The collection is not so much used to build a specific narrative about the past, but instead to introduce the story of a new state from scratch. The museum’s strong focus on the very recent past shifts the spotlight onto events that were taking place within living memory of most of the visitors and seeks to convince people that they amount to the birth of a state.

What makes the Kosovo Museum stand out even more is that its main exhibit is directly linked to a contemporary political aim, which is the full recognition of Kosovo as a state. When a government faces an issue as pressing as gaining a seat at the UN, it is not surprising that cultural policy is geared towards achieving this just as much as foreign policy.

There are other similar museums, particularly in conflict zones where different claims to statehood exist. For example, a large part of the Yasser Arafat Museum in Ramallah is also about Palestine’s image as a state and the meetings of the late leader with foreign diplomats. Not too far away, in 2018, the city of Tel Aviv introduced an “independence trail”, a one-kilometre walk aiming to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the founding of Israel and highlight the history of its independence.

Politics can also be hidden in what museums choose to not highlight. For example, displaying something as simple as an axe, but not mentioning the people who used it and their social conditions, allows the axe to be integrated into a romanticised, sanitised narrative about previous periods of history. In Pristina, the aspects of Kosovo’s history that do not fit into the story of a constant struggle for independence from external forces are omitted from the museum’s exhibitions.

For example, Kosovo’s shared history with Serbia within Communist Yugoslavia is not mentioned. Dealing with this would require the exhibition to not just detail the anti-Albanian policies of the 1990s, but also describe the advances that Albanians made within Yugoslavia, such as the first Albanian-language university in Kosovo being founded in 1969. Centuries of Ottoman rule, which have left a significant cultural legacy including the fact that the majority of Albanians are Muslims, are covered by one display case of weapons and one example of clothes worn at the time.

The fact that many Albanians reconciled themselves with the Ottoman regime, demonstrated by the spread of Islam, does not conform to the narrative of a constant struggle for independence.

Do museums’ inescapable politics excuse their political partiality? No, but it means that museums should reflect on themselves and acknowledge their biases. The stories of minorities should be included in exhibits. Different interpretations of the same events should be presented. More fundamentally, the idea that there is a single, true history needs to be challenged: the different ways in which museums In Kosovo and Serbia deal with the same events illustrates this perfectly. This is an uncontroversial point for historians, but relatively few museums try to communicate this.

Some museums are belatedly waking up to the need to address their political biases. In Belgium for example, there has been an effort to address the country’s role in slavery, to mixed reactions. The Amsterdam Museum recently decided to stop using the term “Golden Age” to refer to the 17th century on the basis that it overlooked issues such as poverty, war and human trafficking. In the UK, there has also been controversy over how the British Museum should deal with the country’s colonial past. While these museums might not be in a place where they have to fight for their country’s existence like in Kosovo, they still affect national politics and people’s perceptions of their nation’s history.

The Kosovo Museum shows us that independent states and nations are not only created through wars and on the negotiating table, but also in the minds of individuals. More generally, cultural institutions serve as a stark reminder that political battles are not only fought by diplomats in dull meeting rooms, but in theatres, libraries and museums.

This article has been prepared as part of wider research and advocacy efforts supported by the Kosovo Foundation for Open Society in the context of the project “Building knowledge about Kosovo”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments