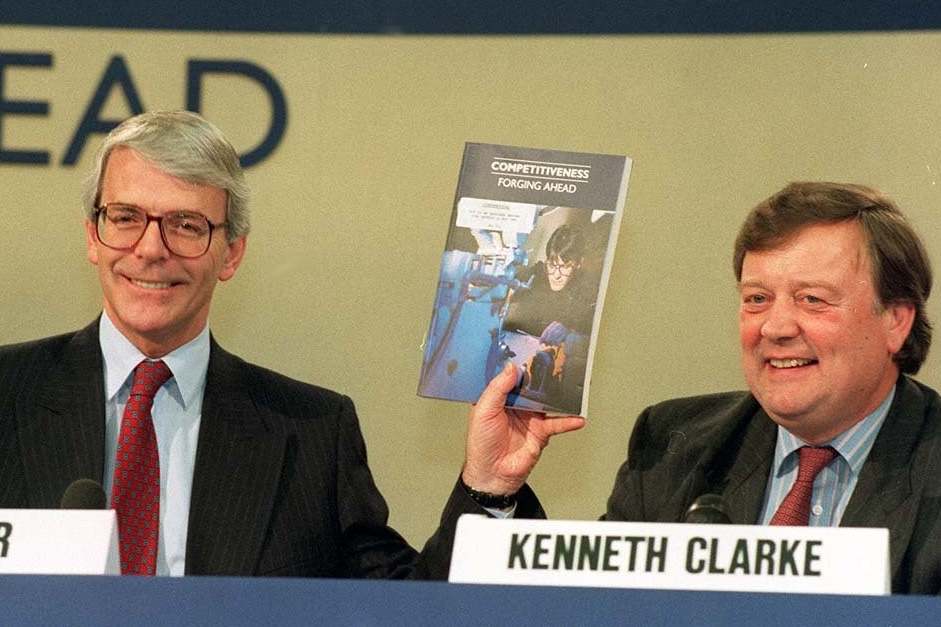

Kenneth Clarke: Without doubt the ‘best prime minister we never had’

He could have made it to 10 Downing Street several times in the past quarter-century, but his resolute adherence to the European ideal meant he was always out of time. John Rentoul salutes a Tory grandee

Now that Ken Clarke has left the House of Commons after 49 years, his chance of becoming prime minister depends on an unlikely sequence of events, including taking a peerage and stepping into No 10 in a crisis. “I wrote a biography of Ken Clarke in 1993 in the expectation that he might soon be prime minister,” wrote Andy McSmith, my former colleague, when MPs voted at the end of last month for an early election. “I’m starting to get a bad feeling it won’t ever happen.”

McSmith’s was one of two biographies of the chancellor published in 1994, a year when politics changed. By then, Clarke’s chances were already receding. Had he been a more cynical politician, that could have been the year he trimmed his sails to the prevailing Eurosceptic mood in the Conservative Party, but he refused to do so. He insisted on keeping the option open for the UK to join the planned single European currency – it didn’t even have a name then – and thus annoyed party members.

By the time McSmith’s book came out, with an image on the cover just of a man’s feet, in suede shoes (not Hush Puppies, Clarke said, but Crockett & Jones), John Major was in deep trouble, and it seemed likely he would be turfed out within months. But Clarke was no longer the shoo-in to succeed him. People have forgotten now how unpopular Major was. More unpopular even than Theresa May at her lowest ebb. Much more unpopular than Boris Johnson is today. His net satisfaction was at minus 54 per cent, at that point the worst ever recorded by a prime minister – a record only ever beaten by Gordon Brown.

It was reasonable to assume that the Conservatives – the ruthless, pragmatic party focused only on doing what it took to hold on to power – would ditch Major and put in someone capable of saving as much as possible from the wreckage of the coming election. Someone, above all, capable of standing up to Tony Blair, who was about to be elected leader of the Labour Party after the death of John Smith in May 1994.

That someone was no longer Kenneth Clarke. Michael Heseltine, the trade secretary, seemed the better choice. Just as much a pro-EU Tory as Clarke, he seemed readier to adjust to Tory Eurosceptic sentiment – and he seemed to have the buckle and swash to fight the fresh-faced appeal of Blair. But Major refused to give up. He fought off threats from both sides of his party in 1995, throwing down a gauntlet to the Eurosceptics that was picked up by John Redwood, who fought and lost a quixotic leadership contest, and coopting Heseltine by making him deputy prime minister.

Clarke’s chance of becoming prime minister was on hold. The great clash between him and Michael Portillo, the tribune of the Eurosceptics, would have to wait until the leadership contest after the general election in 1997. But the landslide that year was so great that Portillo lost his seat. A bittersweet prospect faced Clarke: he seemed certain to become leader of the Conservative Party, but the prospect of overturning Blair’s 179-seat majority now seemed rather remote. And even this prize was denied him when William Hague, 36, having pledged his backing to Michael Howard, changed his mind and ran for it himself.

Clarke was defeated in the third ballot by 90 votes to 72 – the first of two leadership elections in which he was clearly the most able candidate, but which he lost because of his pro-EU views. Four years later, when he probably would have won if the decision had been in the hands of Tory MPs alone, he was defeated in the runoff among party members against Iain Duncan Smith. Hague had changed the rules to give the final say to grassroots members.

Clarke recently accepted that, if he had won in 1997 or 2001, he would have failed to become prime minister, and would probably have gone after the 2005 election. As it was, that was when he contested the leadership a third time. He was eliminated in the first round. That election was won by the special adviser whom he had inherited from Norman Lamont as chancellor, but with whose services he had dispensed. David Cameron was young, smooth, centrist, and just Eurosceptic enough to win two thirds of the party members’ vote.

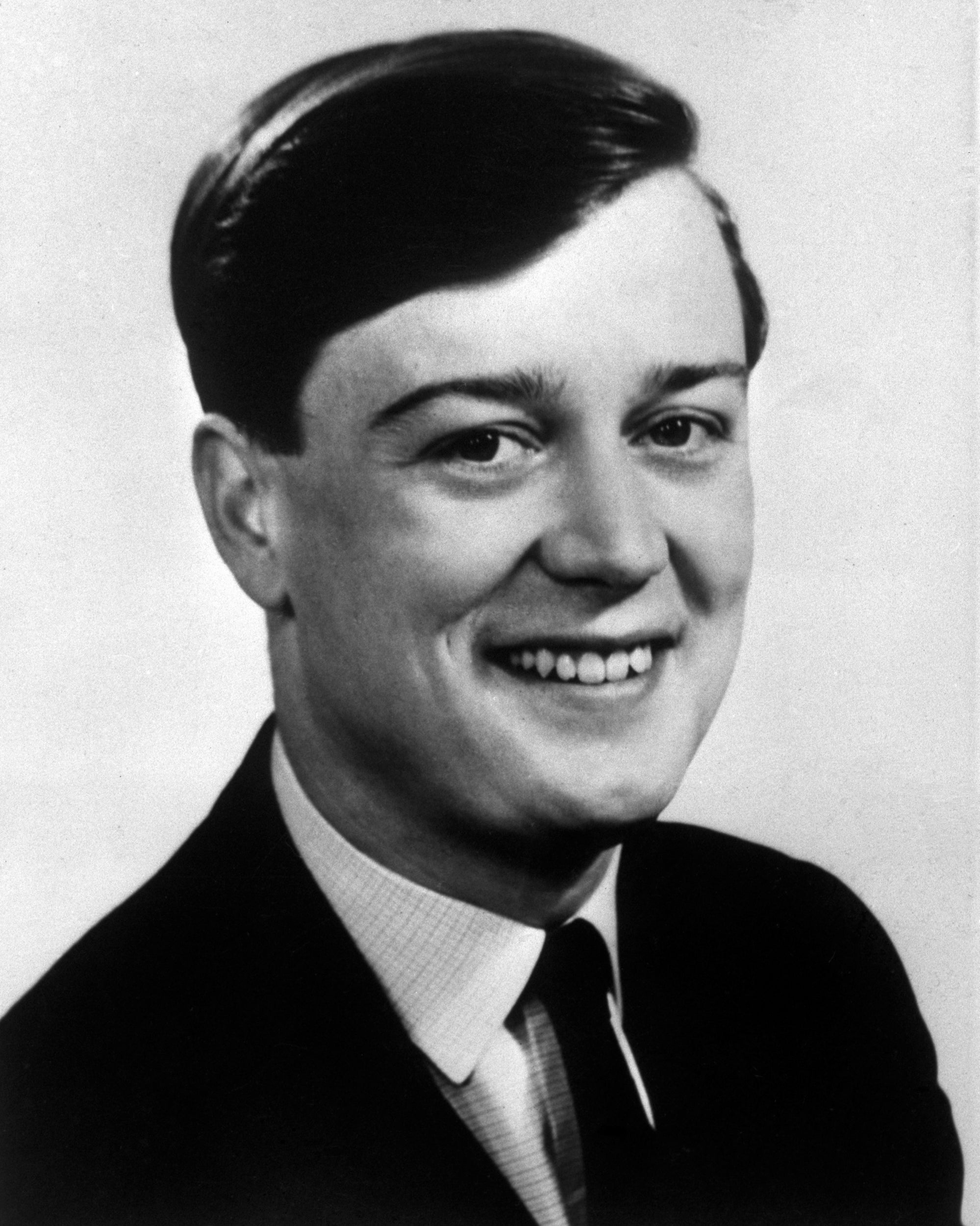

Kenneth Clarke entered the House of Commons in 1970 at the age of 29, when Ted Heath won his surprise victory. As a new MP, he voted to join the European Economic Community, and has been utterly consistent since. He became a junior minister in Margaret Thatcher’s government, and was promoted to the cabinet in 1985 despite being an obvious “wet”.

His ability made him impossible to overlook, so when John Moore, Thatcher’s favourite, crashed and burned, she broke up the giant Department of Health and Social Security and promoted Clarke to run the health part. He was there for only two and a half years, but it was a critical period in the history of the British welfare state. Thatcher wanted to shift to a social insurance model of health care, believing the bureaucracy of the NHS could not be made efficient. Clarke forcefully argued the opposite, combining a political instinct for what Nigel Lawson dismissively called the national religion with a genius for administration.

Clarke’s devolution of power to self-governing hospital trusts started reforms that paved the way for New Labour’s success in delivering better services when higher spending started to come through. But the ideological significance of his victory over Thatcher was that it started to turn the Tory party away from the idea of breaking up and privatising public services. It wasn’t until Michael Howard’s time as leader that the idea of the “patient’s passport” – a way to subsidise people who chose to go private for treatment – was finally abandoned, but it was doomed from the moment Clarke won that battle in 1989.

From then on, he was qualified to be prime minister. The most important and least appreciated qualification for high office is temperament, and Clarke had it. His affability and confidence gave him a huge advantage. Civil servants loved working for him because he would make decisions with an air of not having to try too hard.

Unfortunately for him, his immense confidence arose from firm beliefs, above all in Britain’s place in Europe. The very quality that meant he would have been a good prime minister also ensured that he would never have the chance to put this to the test: at the very moment he graduated to the top rank of politics in the twilight of the Thatcher period, the Conservative Party was undergoing a historic shift to Euroscepticism (and Labour, meanwhile, was crossing the spectrum in the opposite direction).

He was already by then a slightly old-fashioned politician. He had a hinterland – jazz, birdwatching, motor racing – and the culture shift when Brown succeeded him at the Treasury was marked. Civil servants tell the story of the new chancellor trying to get into the building early on Saturday morning after the election. Clarke had not been expected in the office until 10am, and then only on weekdays.

He enjoyed wine and cigars. When it was put to Clarke as health secretary that smoking should be banned in enclosed public spaces, his only response was to blow a cloud of smoke in the direction of the suggestion.

There was a darker side to this insouciance, though, which was Clarke’s position as deputy chair of British American Tobacco, 1998-2007, during much of the Conservative party’s period in opposition, when he was also a shadow minister. He was serenely untroubled by the ethics of taking big tobacco’s shilling, or by the suggestion that there might be a conflict of interest with his political role. I should record that he was also a director of The Independent at this time, a responsibility he took seriously and discharged diligently.

He was a streetfighting politician, who used words carefully: that is not a contradiction, because so much of political debate is about language, and avoiding words that your opponents might use against you. I saw a flash of this when he came to a class at King’s College London taught by Nick Macpherson, who had been his private secretary at the Treasury, and Ed Balls, special adviser to Clarke’s successor as chancellor.

Clarke said he – along with all former chancellors except John Major – had always been in favour of an independent Bank of England. Balls interrupted to point out that Clarke had opposed it when Brown had consulted him before making the announcement in 1997. Clarke said that if you studied his words, you would find that he did not commit himself on the principle. Ten years after the event, he had a razor sharp memory for the subtleties he had deployed. (I went back and checked; he said: “What you are going to see, undoubtedly, is tighter monetary policy than you might otherwise have got…” In other words, he implied Bank independence was a bad idea without saying so.)

So it was no surprise that David Cameron brought Clarke, at the age of 69, back to the cabinet as justice secretary in 2010. He was the most experienced senior minister, but caused the prime minister no end of trouble. Cameron described him as the sixth Lib Dem in his cabinet, and said he found it easier to work with the five actual Lib Dems than with the one who was nominally a member of his own party.

A classic liberal Tory, Clarke had no patience with home secretary Theresa May’s restrictive policy on immigration and her populist campaign to pull out of the European Convention on Human Rights. At an earlier stage in his career, he might have been more discreet, but by now he was beginning to enjoy his reputation as the bad boy of One Nation Toryism. So Cameron shifted him to minister without portfolio in 2012, and Clarke left the cabinet in 2014.

His wife Gillian died in 2015, yet he remained a genial and talkative grandee, always happy to embarrass his leader – calling May a “bloody difficult woman” in the 2017 election – and always ready to exchange his cheery assessment of politics with passing journalists – which was usually along the lines of, “No one has the slightest idea what will happen next.”

After the 2016 EU referendum, Clarke enjoyed an Indian summer as one of the leading voices for moderation. He accepted the result, but argued for the softest Brexit possible, keeping the UK closely aligned with the EU single market. He voted for Theresa May’s deal, but when she failed and Boris Johnson took over, he enjoyed his final hurrah. He emerged as the natural candidate to be temporary prime minister if such a device were the only way to stop a no-deal Brexit. He returned from a two-week holiday in Norway in August, and affected bemusement at the clamour for him to stand ready to take over at the head of a possible caretaker government, but said: “If they ask me to lead, yes I would lead it.”

At that point, this was a plausible scenario. Many MPs thought it wouldn’t be possible to legislate against a no-deal Brexit, in which case the only way to stop Johnson carrying out his threat to take the country out, “deal or no deal”, would be to bring him down by a vote of no confidence. If the opposition parties and Tory rebels could work together, they could then install a temporary prime minister for the limited purposes of agreeing a Brexit extension and holding a general election. A new prime minister would be needed before the election was called to prevent Johnson leaving the EU without a deal while parliament was dissolved during the election campaign.

Oddly enough, an extension was agreed and an election announced anyway, but that was achieved by passing a law to block a no-deal exit, rather than by finally putting Clarke in 10 Downing Street, 26 years after Andy McSmith first thought he might be prime minister.

So that is the end of Clarke’s 49 years as an MP: a rich career of ministerial service and one of the longest-serving holders of the title of “best prime minister we never had”. He ends it as one of a band of 21 MPs who were expelled from the parliamentary Tory party for voting for more time to consider the legislation to enact Johnson’s Brexit deal. Clarke leaves parliament as the spiritual leader of liberal, One Nation, pro-EU Conservatism; the natural prime minister of a party that was eclipsed by New Labour. It was surprising, in many ways, that pro-EU Toryism survived for so long, but Clarke’s departure from the House of Commons, no longer officially a Conservative MP, is a vivid marker of the end of that strand of politics.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments