Keir Starmer has found a role in the war against trickle-down economics

The Labour leader finally has a clear purpose. His task at the party’s annual conference is to maximise his ideological advantage, writes John Rentoul

A year ago, Labour looked like “a party searching for a problem the country might want it to solve”, according to the Financial Times. The most important thing that has happened to Keir Starmer since then is that he has found one.

On the energy price crisis, Labour has led the way. From the start, as inflation surged, the opposition urged Rishi Sunak to do more to help people on low to middle incomes. And Labour proposed a windfall tax on the oil and gas companies to help pay for it, as world prices rose, even before the invasion of Ukraine in February.

As the crisis escalated, Sunak was forced to follow, announcing more help with energy bills in May, partly funded by a windfall tax. The world gas price continued to rise, and Starmer responded by proposing an energy price freeze. Wise heads said that it would be too expensive and would give taxpayers’ cash to people who didn’t need it. But it was easy to understand, and offered reassurance at a frightening time. So Liz Truss, while preparing to become prime minister, junked her free-market principles and adopted Labour’s policy.

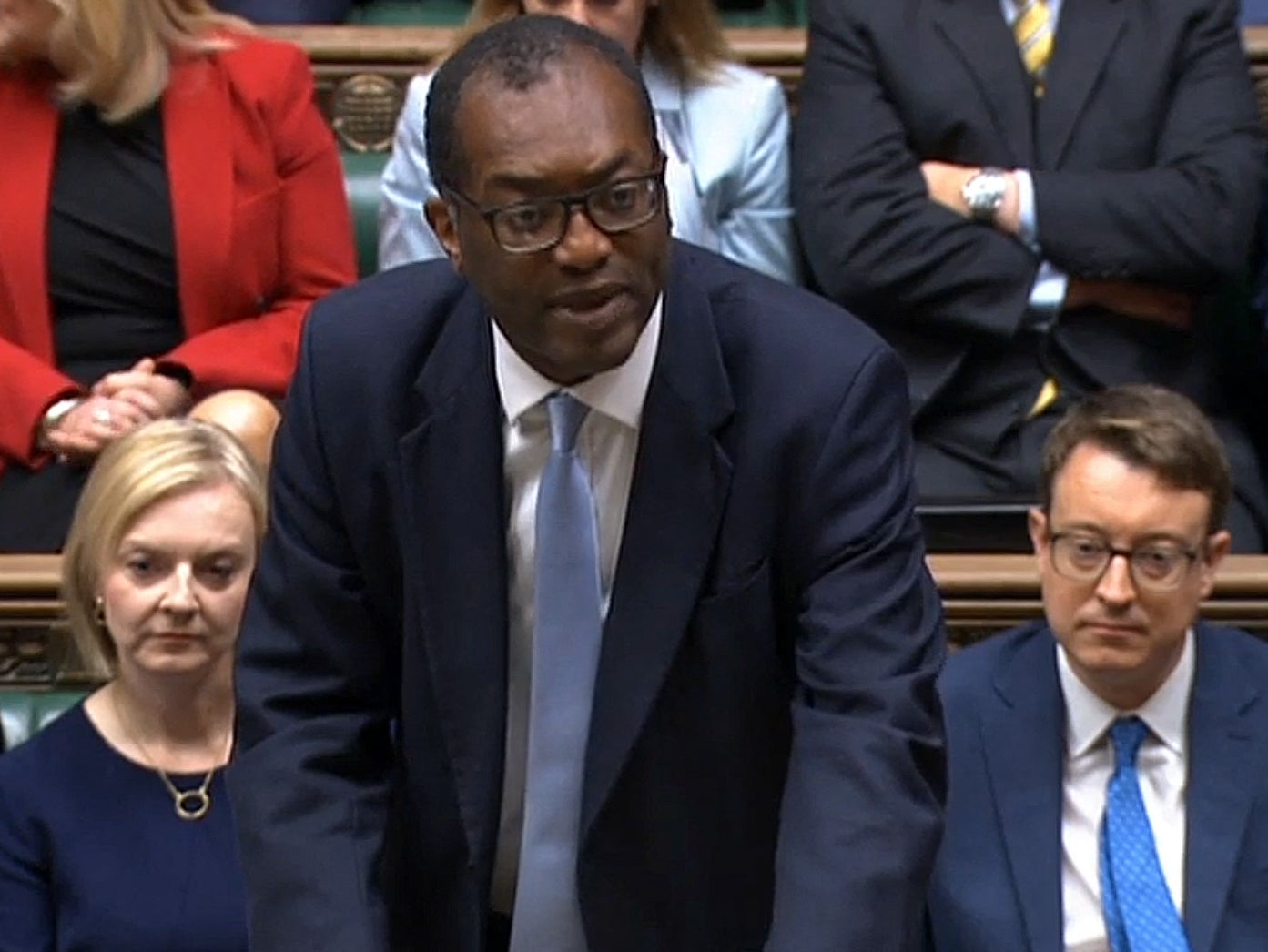

This week, Kwasi Kwarteng and Jacob Rees-Mogg confirmed that Starmer and Rachel Reeves, the shadow chancellor, had won the argument. But there remains a clear strip of ideological territory between the two parties, and Starmer’s task at Labour’s annual conference in Liverpool over the next few days is to maximise his advantage.

He and Reeves continue to argue for a heavier windfall tax, and for tax cuts tilted towards helping those on lower incomes. Theirs is a simple message: that they know how to promote economic growth in a way that is socially just and fiscally sustainable. They have been handed a priceless gift by Truss and Kwarteng, who are cutting taxes for the rich and letting oil and gas companies keep more of their windfall profits – paid for by higher borrowing. A gift tied up in a ribbon carrying the legend: “Bigger bonuses for bankers.”

This means that Starmer will have an unusual advantage in his leader’s speech on Tuesday: he has a clear message, a clear difference with the government, and he is on the side of public opinion. Both Starmer and Truss will claim in their party conference speeches that they can deliver growth, but Starmer believes that “the political dividing line is how you see growth delivered”, according to a Labour source: “from the top down or the bottom up – Liz Truss is on the side of a failed trickle-down economics”.

What is uncanny is that I had that conversation with the Labour source three days before Joe Biden tweeted a remarkably similar form of words on Tuesday: “I am sick and tired of trickle-down economics. It has never worked. We’re building an economy from the bottom up and middle out.” It shows how Starmer takes some cues from the election campaign that produced Biden’s victory over Donald Trump two years ago, but it also shows how Truss’s tax cuts for the better off have opened up “trickle-down” as a dividing line in British politics.

Truss’s claim that tax cuts for the rich will benefit the whole country will help Starmer sell a different pro-growth message: prosperity for the many, not the few

Those, then, are going to be the themes of Starmer’s speech. They have been rehearsed in a couple of recent speeches of his, which did not get the kind of coverage he hoped for, mainly because the Conservative leadership campaign was still in full flood. “Labour will fight the next election on economic growth. The first line of the first page of our offer will be about wealth creation,” he said in Gateshead on 11 July.

There is a striking similarity between the two main parties in the way they frame the objective. “I have told the shadow cabinet that every policy they bring forward will be judged by the contribution it makes to growth and productivity,” said Starmer in Liverpool – where Labour’s conference meets this weekend – on 25 July. Compare this with the government’s Growth Plan, published with Kwarteng’s mini-Budget earlier today, which said: “Economic growth is the government’s central mission ... requiring each policy and initiative to be measured against a defining test of whether it helps or hinders growth.”

The focus on growth from both main parties may seem dissonant at a time when the British economy is flat on its back, and the main priority for the next two years is to avoid a deep recession, but the two parties are positioning themselves for the next election. Some of Starmer’s supporters on Labour’s national executive committee (NEC) are allowing themselves to believe that the energy crisis might be “the moment when the Tory reputation for economic management suffers the kind of damage” it sustained 30 years ago when John Major’s exchange rate policy collapsed.

But even if Truss is lucky with world gas prices, and gets the British economy through in one piece to what everyone expects to be the election year (2024), it looks as if there will be a clear ideological difference between the parties, summed up in that “trickle-down” phrase. Truss is gambling on the idea that, although her abolition of the top income tax rate for the richest 1 per cent may be unpopular, it will nevertheless convey a simple message: that she is focused only on growth; Starmer is happy to fight the election arguing that growth should be “bottom-up” rather than “trickle-down”.

He recognised that this might pose a challenge to some Labour members: “We won’t retreat to a comfort zone on public services and hope the focus of the country shifts ... The approach to growth I have set out today will challenge my party’s instincts. It pushes us to care as much about growth and productivity as we have done in the past about redistribution and investment.”

I am told that a section of Starmer’s conference speech will be about how “Britain is living through a moment of profound change”, and how a Labour government will help the country to seize the opportunities of artificial intelligence and other hi-tech buzz phrases.

Truss’s claim that tax cuts for the rich will benefit the whole country helps Starmer to sell a different pro-growth message: prosperity for the many, not the few. But he will have to make himself heard above the usual hubbub and distraction of Labour’s annual get-together. There will be a fuss about singing the national anthem, although that will probably pass off uneventfully. “In any other country, the main centre-left party would sing the national anthem,” a current member of the NEC told me. Labour elder statespeople affect to be baffled by the alleged controversy. “We’re a patriotic party,” said Lord Mandelson this week.

The Corbynites are trying to engineer a vote on nationalisation. Starmer’s line is that public ownership is a distraction from the immediate problems of the energy market

There will be rows about some of the issues that Starmer doesn’t want to be debated or voted on. With a small majority of constituency delegates supportive of the leadership, most of the Corbynite assaults will be fended off. Momentum – the Corbyn leadership campaign turned fan club – is not the force it once was. It held a “primary” vote of its members in April to choose the motions it wanted to prioritise, and only 2,500 people took part, compared with the 7,400 who voted to choose Momentum’s candidate for the leadership (Rebecca Long-Bailey) in January 2020. Look out for the election of members of the national constitutional committee. This will be significant, both as an indication of the strength of the Starmer loyalist slate, and for future disciplinary cases (although cases related to antisemitism are now dealt with by a separate, independent mechanism).

The Corbynites are trying to engineer a vote on nationalisation. Starmer’s line is that public ownership is a distraction from the immediate problems of the energy market in particular, and is not a priority for public spending. So far, attempts to force a vote have been frustrated, but there is more procedural wrangling to come. There will be further such manoeuvring over support for “workers in struggle”, and what one Starmerite sarcastically referred to as motions to “make it compulsory to go on picket lines”. (This is only a slight exaggeration: one of Momentum’s prioritised motions demands the repeal of “all anti-trade-union laws” and commits the party “to always supporting striking workers”.)

One of the leader’s supporters argued that Starmer would probably lose some votes, but these would be embarrassments rather than substantive reverses, as conference resolutions do not bind a Labour government. And Starmer’s office was delighted to discover that, in one indication of significant change, local parties have failed to submit a single motion on the Middle East, meaning that there will be no sea of Palestinian flags this year.

The big question on which the conference will not go Starmer’s way is electoral reform. I am told that Starmer is “relaxed” about a motion in favour of proportional representation (PR) being carried by a large majority. So relaxed that he strained every sinew and called in every favour to organise the trade union block votes to crush an overwhelming vote by local parties for PR last year. He cannot do that this year, because the two biggest affiliated unions, Unison and Unite, have both switched from opposing PR to supporting it. So he has decided to make a virtue of necessity by pretending to be open-minded. “Our only red line is using it to advocate ‘progressive alliance’ crap,” said a source close to Starmer.

The Labour leader is happy to use his party’s support for PR as an incentive to informal cooperation with the Liberal Democrats, but refuses to countenance a pre-election pact by which the parties stand candidates down in each other’s favour. Starmer’s position is helped by the failure of electoral reformers to agree on which form of PR they should advocate: the Lib Dems prefer preferential voting in multi-member constituencies, as in Ireland; Labour reformers tend to want an additional-member system, like the one used by the Scottish parliament.

Starmer’s main concern is that a big controversy over PR would give the impression that Labour thinks it cannot win and, more seriously, that it would distract from his “growth for all” message. His greatest ally in getting his message across, though, turns out to be Truss.

With the Labour conference coming immediately after an emergency Budget that has cut the top rate of income tax, uncapped bankers’ bonuses and allowed oil and gas companies to keep more of their windfall profits, Starmer and Reeves have an unparalleled opportunity to offer an alternative aimed at prosperity for the many, not the few.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments