Why have we turned our backs on sacred outcast Julian Assange?

Nothing about his case is fair: his crime was simply to expose corruption. The press loved him, then abandoned him. We need to understand his banishment before it is too late, urges Patrick Lawrence

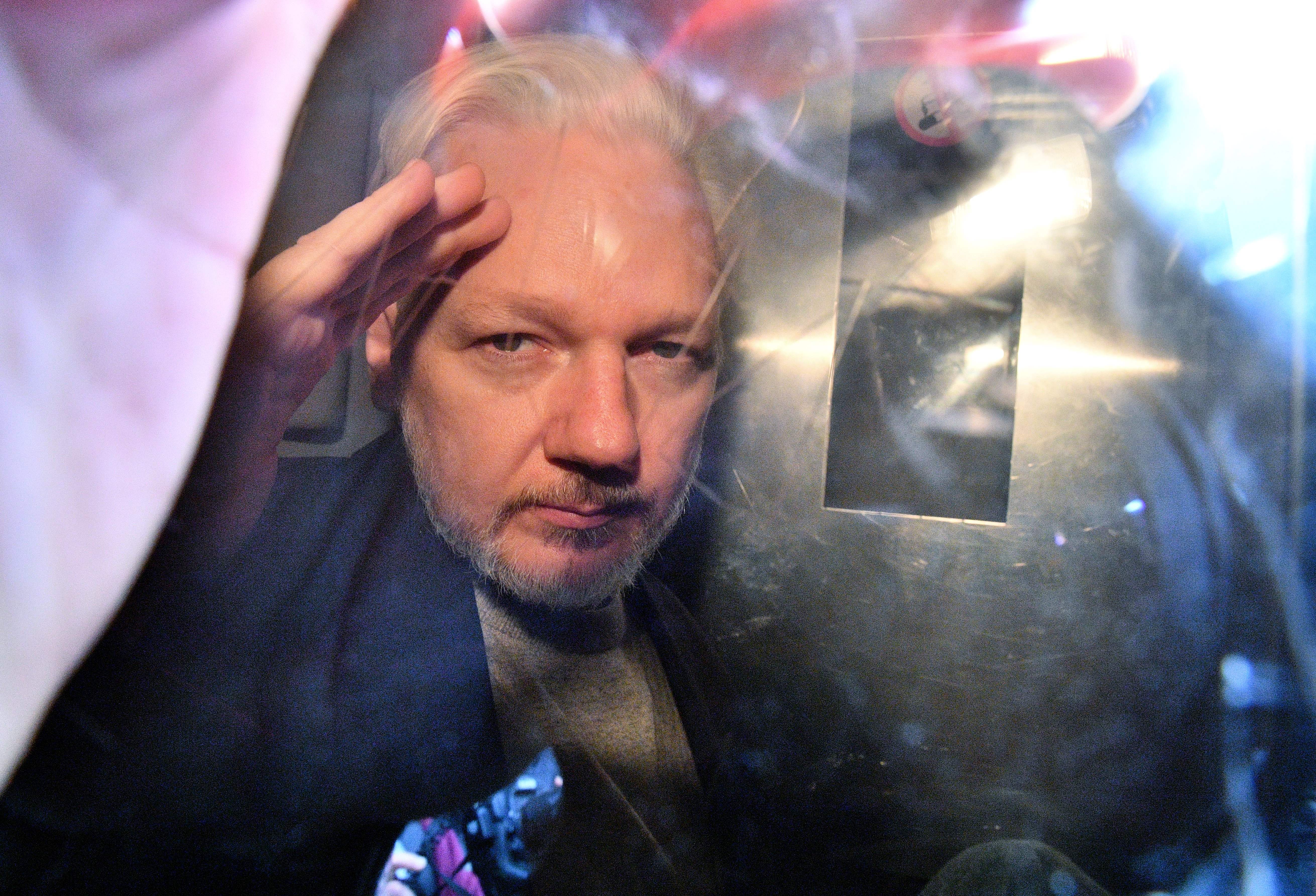

Of all the images of Julian Assange made public over the years, three are indelibly haunting, even if, as we look at them, their import comes to us subliminally. These pictures date to the spring and autumn of 2019, when the WikiLeaks founder was arrested and imprisoned in London as a British court considered an American extradition request. In all three, he is photographed behind a pane of glass, a little as if he were a sea creature in an aquarium — near, yet beyond our reach. In all three, he is confined in a security van about to take him away from crowds of press people, supporters and, we have to assume, some stray passersby.

These are pictures of departures, then. When we look at them we find ourselves among those gathered at the scene and left behind. On the other side of the glass, with its strange reflections and refracted light, Assange is framed for us. He is remote within the frame, as figures in portrait paintings are remote. Even as he leaves us, Assange is already gone.

There is a Reuters photograph taken on 11 April 2019, the day Assange was arrested. Plainclothes police officers have carried him, corpse-like, down the steps of the Ecuadorian embassy in Knightsbridge. His hair is long and brushed back severely, and he wears an unruly beard. From the police van’s window he offers a resolute stare. Handcuffed, he raises both forearms to manage a thumbs-up gesture. The band of a London cop’s cap is visible behind him.

In an Associated Press photograph dated 1 May, a police van is taking Assange from a court appearance back to Belmarsh, a maximum-security prison in southeast London. His hair is short and his beard trimmed. His stare again conveys resolve. Assange holds up his left hand and curls his fingers into a fist. To his left in the picture plane, the glass reflects the distorted image of a brick apartment block. To his right, the flash of a camera illuminates an icy steel door just behind him.

The third image is a still from a video recorded after Assange had appeared in Westminster Magistrates Court on 21 October. He is in the window of a van that belongs to GEOAmey, a private company that provides “secure prisoner transportation and custody services”. Behind him is a steel door similar to the one in the second photograph, again illuminated by the flash of a camera. Assange is clean-shaven, gazing into the middle distance somewhere just above his head. The resolute stare is gone. Assange has no sign for us — we on the other side of the windowpane— no thumbs-up, no clenched fist. Some new kind of silence — a totalised, internalised silence — has been added to the silence imposed on Assange at the time of his arrest.

These images span six months. To place them side by side is to detect in outline the story of a very eventful half year in the life of Julian Assange. They are to me like shards of a broken bowl. Holding fragments of pottery in one’s hand, one imagines the unseen whole, the object that is no more. So it is with my prints of the Assange photographs. I spread them on my desk. I study them. They seem to me tiny pieces of a shattered life, a life deprived, a life by turns taken away.

The story the images tell is Assange’s but also ours, in some measure the story of the way we in western democracies (or post-democracies) now live. In this way the three pictures are mirrors, held up to us that we see ourselves as we are.

The story of Julian Assange’s arrest in April 2019 begins in another April, this one nine years earlier. Assange’s exceptional endurance aside, there is nothing to admire in this story, much to hold in contempt. It is a story of false charges, cynical fabrications, unscrupulous prosecutors and judges, incessant breaches of law. There is physical abuse and psychological torture. Sweden, Britain, and latterly Ecuador have all conspired to deliver Assange to the United States for the offence, as is often noted, of breaching official walls of secrecy to expose multiple crimes, corruptions, and cover-ups. Assange is not charged with lying or disinformation or calumny or libel or anything else of this sort. The crime is exposure, shining the light of day where it must not shine.

I have wondered while writing this essay whether Assange will ever again see the sky but from a walled and concertina-wired prison yard. At writing, his hour draws near. His lawyers failed to adjourn a hearing earlier this month. That four-week hearing of the evidence concluded last Friday, 2 October, and the ruling will be made on 4 January. It is a foregone conclusion. There will almost certainly be an appeal. And again, almost certainly, it is only a matter of time before Assange is put on a plane to face trial in a federal court in Virginia where such cases are typically heard and ruled upon. This verdict is another foregone conclusion. To describe these as show trials is perfectly responsible. And it is part of the argument here that we must be mindful of the history and connotations this freighted term bears.

To return to that earlier April: on 5 April 2010 WikiLeaks released Collateral Murder, the swiftly infamous video of a US Army helicopter crew’s mid–2007 attack on unarmed civilians in Baghdad. Three months later came “Afghan War Diary,” 75,000 documents that devastated official accounts of America’s post–2001 campaign in Afghanistan. These were two of the most damaging leaks in US military history. For the first time in its brief life, WikiLeaks had penetrated deeply into the citadels of official secrecy. This was stunningly confirmed with the release of “Iraq War Logs” (nearly 392,000 Army field reports) in October 2010 and, a month later, the phased publication of “Cablegate”, a collection of State Department email messages that now comes to more than three million.

All of these releases derived from Assange’s work with Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning. They were a blunt challenge to the ever-advancing sequestration of power in our post-democracies and — let us say this now — to practices of mis- and disinformation that have long been routine in institutional Washington and the capitals of allied nations.

The 2010 publications stunned the Obama administration and the national-security apparatus invisibly but formidably behind it. There is much to suggest, on the basis of what is known, that Washington soon prevailed upon cooperative allies to encumber Assange with all manner of criminal charges, however far-fetched, trivial, or unrelated to the work of WikiLeaks these may be.

Stratfor, a Texas company that provides intelligence services to a variety of defence contractors and federal government departments, began issuing directives of this kind within weeks of the “Cablegate” releases. “Pile on,” one of its advisories reads. “Move him from country to country to face various charges for the next 25 years.” It was WikiLeaks, ironically enough, that revealed these communications in a 2012 release called “The Global Intelligence Files”.

While teleologies cannot be countenanced, what Stratfor recommended — to official clients in Washington, we can cautiously assume — is a strikingly apt description of Assange’s fraught odyssey during the nine years prior to his 2019 arrest. Shortly after the release of “Afghan War Logs”, Swedish prosecutors alleged that Assange had raped two women while in Stockholm for a media conference. These allegations would haunt Assange for many years.

We now know, thanks to an investigation by Nils Melzer, the UN’s special rapporteur for torture, that the Swedish case rested on corrupted police reports and fabricated evidence. Not even the two women with whom Assange had consensual relations supported prosecuting Assange on rape charges. Assange volunteered a statement to the Swedish police after prosecutors leaked falsified accusations to a Stockholm tabloid. He waited five weeks to be questioned, but Swedish authorities never brought him in. In autumn 2010 he decamped for London on his attorney’s advice and with Stockholm’s assent.

With the coordination of trapeze artists, Britain took over where Sweden had left off. British authorities arrested Assange two months after his arrival, citing a sudden Swedish request for his extradition. While released on bail, Assange took asylum at the Ecuadorian Embassy when Sweden declined to confirm that it would not re-extradite him to the United States were he to return to Stockholm to cooperate with Swedish investigators, as Assange wished to do.

In time, the Swedish case melted like ice cream in the sun. Prosecutors formally dropped their case on 19 November 2019. They had never charged Assange with any offence, and no allegation was ever substantiated, but they had done their work: by this time an obliging new government in Ecuador, acting at Washington’s behest, had canceled Assange’s asylum. He was arrested for violating the terms of his bail but was immediately faced with another extradition order — this one from the United States. Country to country, charge to charge: Sweden, Britain, and Ecuador acted, oddly enough, according to the design Stratfor had earlier proposed.

The Justice Department’s initial request for Assange’s extradition was unsealed the day he was carried out of the embassy. He was charged with a single count of conspiracy to compromise a government computer — this during his work with Manning — and faced a maximum sentence of five years. It seemed at the time an oddly modest case and an oddly modest penalty given the extreme animosity official Washington had nursed since Assange published the Manning documents in 2010. But more and much worse was shortly to come. On 23 May, six weeks after his arrest, a district court in Virginia unsealed indictments charging Assange with 17 additional offences — these filed under the 1917 Espionage Act. This was a precipitous escalation of the American case. Assange suddenly faced sentences of up to one 175 years should he be extradited and found guilty of all 18 charges now lodged against him.

“Like many young people, I wanted to be on the cutting edge of civilisation. Where were things going? I wanted to be on this edge. In fact, I wanted to get in front of this edge of the development of civilisation. Because the old people were not already there.”

That is Julian Assange talking to Ai Weiwei in 2015. The noted Chinese artist had visited Assange three years into his asylum with the Ecuadorians. Their exchange is a contribution to In Defense of Julian Assange, a compendium of commentaries published a few months after Assange’s arrest at the embassy. “If you could learn fast you could get in front of where civilisation was going,” Assange said the September day he and Ai conversed. “So I tried to do that, and I was pretty good at it.”

Assange became pretty good at it at a young age. He was hacking into the email queues of Pentagon generals while still a teenager in Australia. He understood very early that to be on the front edge of civilisation meant penetrating the walls of secrecy behind which our most essential institutions — of government, statecraft, intelligence, defence — set the course of an ever more globalised civilisation.

Assange’s thought was not his alone. By the time he was scoring his first hacking hits, it was plain that a “culture of secrecy” — Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s phrase — had grown like kudzu all around us. In Secrecy, Moynihan’s 1998 survey of the phenomenon, the late senator wrote of “secrecy centres” throughout the American government, of “the routinisation of secrecy”, of “concealment as a modus ivendi”. Something called the Information Security Oversight Office — a secret in itself to most of us — each year totes up the number of secrets government bodies created during the previous 12 months. As Moynihan explained, in essence the ISSO counts the documents classified in a given year. These, too, seem to grow year to year like a weed.

Assange’s original contributions to the questions of secrecy and concealment are four. One, he recognised, without inhibition and without allegiance to any orthodoxy, that our political culture’s infinitely elaborated structures of secrecy are, indeed, where civilisation is going. At this point, it is commonly assumed among paying-attention people that a small proportion of what our government decides and does is visible to us.

Two, Assange understood that these structures must be penetrated if authentic forms of democracy are to survive. Hence his thought as to where the edge of civilisation lies. Three, Assange saw the vital, make-or-break responsibility of the press if the walls of secrecy are to be dismantled. Finally, he devised an extraordinarily innovative means to open up these structures — the national-security state and its numerous appendages — for the first time since this tentacled organism began to develop in the years after the Second World War.

Assange registered “WikiLeaks” as a domain name in Iceland on 4 October 2006. The site’s early publications were small bore — a Somali rebel’s assassination plots, the leaked emails of Sarah Palin, then a vice-presidential candidate — but its potential as a technology and a means to protect sources was immediately evident. In these early years, WikiLeaks was understood to promise something very new in journalism, a resource that could fundamentally alter relations between those practicing the craft and the powers they reported upon. Traditional media initially embraced WikiLeaks; governments cast a cold eye for the same reasons.

Whistle-blowing and the exposure of the officially hidden have long and honourable traditions, in America and elsewhere

All of the major releases of 2010, WikiLeaks’ breakout year, derived from the Assange–Manning connection. Their work was made of what reporters and sources do in countless such interactions daily: Manning gave a journalist a story and evidence to support it; Assange cultivated his source and published the story. No serious appraisal of their relationship can otherwise describe what they did. But it is this relationship that the Justice Department deems a criminal conspiracy. This was the charge in the indictment unsealed the day of Assange’s arrest at the Ecuadorian Embassy.

It is not clear, even now, how many sets of documents Manning conveyed to WikiLeaks. In “Gitmo Files”, published in April 2011, WikiLeaks lifted the lid on the Army’s shockingly cavalier treatment of captives at Guantánamo Bay. On 24 June 2020, the Justice Department filed a superseding indictment against Assange, in which it alleges that Manning was also the source of these documents. In my view this is almost certainly so, but as WikiLeaks does not reveal its sources — Assange’s most essential principle — the origin of “Gitmo Files” has never been established. However this may be, it was not until the Guardian and other newspapers began publishing parts of Edward Snowden’s immense data trove, in the summer of 2013, that any breach of secrecy matched in magnitude the releases Manning had given Assange.

Manning and Assange paid, and paid swiftly, for their fruitful collaboration. Sweden and Britain soon had Assange careening through a hall of mirrors made of largely manufactured allegations. Manning was arrested a month after WikiLeaks released “Collateral Murder”. She then faced the first of numerous charges and was sentenced to 35 years’ imprisonment three years later. Manning’s treatment while detained was not much different from what awaited Assange at Belmarsh: it was harsh and in breach of law.

At the Quantico Marine Corps base, where Manning was initially held, she was deprived of sleep, confined to solitary for long periods in a windowless 6-by-12-foot cell, and at times stripped to her underwear. Juan Méndez, at this time the UN’s rapporteur for torture, described these and other conditions as “cruel, inhuman, and degrading”. It is unusual and by definition cruel that Manning was subsequently imprisoned at Fort Leavenworth, a men’s military prison, despite having announced just prior to her sentencing that she identified as a woman. By 2016, three years into her sentence, she had attempted suicide twice.

Three days before vacating the White House in January 2017, Barack Obama commuted all but four months of Chelsea Manning’s remaining sentence — roughly 28 years of it. Her freedom was brief. In March 2019, she was rearrested on contempt charges after refusing to testify before a grand jury investigating Assange.

Prosecutors knew Manning’s story well enough: she could not have spoken more plainly when she was first arrested. She had submitted to extensive questioning, confessed, and pleaded guilty at her earlier trial. They needed one thing from her this second time around: they needed her to support their conspiracy case against Assange. Manning had earlier testified that she acted alone when she hacked government computer systems. Now they wanted some indication, however scant, that Assange had directed her. An incautious phrase would do. Manning gave them nothing. “I will not participate in a secret process that I morally object to,” Manning stated, “particularly one that has historically been used to entrap and persecute activists for protected political speech.”

I will not participate in a secret process that I morally object to, particularly one that has historically been used to entrap and persecute activists for protected political speech

Manning returned to prison, this time to the women’s wing of a federal facility, on 8 March 2019. There she remained for a year, keeping the faith. On 11 March 2020 Manning made a third suicide attempt. A federal judge ordered her release the following day.

Whistle-blowing and the exposure of the officially hidden have long and honourable traditions, in America and elsewhere. As one would logically expect, challenges to our empires of secrecy have grown more frequent along with the grotesque expansion of these antidemocratic domains. This has proceeded in consonance with the elaboration of the national-security state, beginning with Truman’s fateful directive in 1952 — kept secret for decades afterward — to authorise the new National Security Agency. The imperium we now live within, we may fairly say, has from the first been a furtive, undeclared and unnamed, there-and-not-there undertaking — secrets comprising its walls. With the keepers of secrets, more or less inevitably, come the breakers of secrets.

There are some illustrious names among the leakers and whistle-blowers of our recent past. Most people’s lists begin with Daniel Ellsberg, he who passed the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times in 1971. Mark Felt, a career FBI official, was the Deep Throat of the Watergate scandal, although his name was made public only in 2005. Let us not forget Samuel Provance, the Army intelligence officer who exposed abusive practices at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq in 2004, along with the attempted cover-up that followed.

The list must go on and on, too many exemplary figures to mention. Bill Binney, Kirk Wiebe, Ed Loomis, and Tom Drake were senior NSA officials when, in the early years of our century, they exposed the corruptions associated with the agency’s now-infamous surveillance systems. These four had a curious ancestor worth noting. Herbert Yardley directed the Cipher Bureau when, in 1931, he exposed the first monitoring and surveillance practices of an early iteration of the NSA.

Julian Assange cannot properly be assigned a place on any such roll call. His work concerns whistle-blowing, but he is a journalist and publisher with no whistles of his own to blow. Assange’s bravery when confronted with questions of principle and integrity, and the magnitude of what he determined to do, are the match of anyone’s in the truth-telling tradition. But we cannot tuck Assange neatly into any file. His fate sets him apart, just as the figure we now see behind glass is apart from us. There is an historical discontinuity, too. What has been done to Assange since his arrest and detention, how, and by whom, is to be understood only by way of the most disturbing precedents. Let us call this the colonisation of Assange’s being — every aspect of it — by legal authorities with (a paradox here) no legal authority to act toward Assange as they do.

About a month after Assange was sent to Belmarsh, he wrote a letter to Gordon Dimmack, an activist (and self-fashioned journalist) who follows the Assange case. At the time, Assange and his defence attorneys were trying to frame their case against the American extradition request. In Defense of Julian Assange includes part of this letter. Here is a brief passage:

“I have been isolated from all ability to prepare to defend myself. . . .I am unbroken albeit literally surrounded by murderers. But the days when I could read and speak and organise to defend myself, my ideals and my people are over until I am free.”

This letter is dated 13 May 2019. At a preliminary extradition hearing shortly afterward, Assange’s attorneys stated that their client was too ill to appear in court, even via video from Belmarsh. On the same day, WikiLeaks announced that Assange had been moved to the prison’s hospital wing. One of his defence attorneys said at this time that on meeting Assange “it was not possible to conduct a normal conversation with him”.

A day later, Nils Melzer, the UN’s rapporteur for torture, made public his findings on examining Assange, not quite a month after his arrest, in the company of medical experts. These were the first indications that Assange was being mistreated at Belmarsh. Here is part of what Melzer wrote:

“The evidence is overwhelming and clear. Mr Assange has been deliberately exposed, for a period of several years, to progressively severe forms of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, the cumulative effect of which can only be described as psychological torture.”

But his physical appearance was not as shocking as his mental deterioration. When asked to give his name and date of birth, he struggled visibly over several seconds to recall both

Assange next appeared in public on 21 October last year, the date of the third image considered earlier, when he attended another preliminary hearing at the Westminster Magistrates Court. This was an important occasion. Craig Murray was among those in court that day. Murray, a Scot and a former Foreign Office diplomat, stands among Assange’s most dedicated supporters. The day after the Westminster hearing, he published a lengthy piece on his website. It circulated widely — no surprise given its astonishing account of Assange’s enfeebled appearance and the wilful corruptions evident throughout the proceeding. I will quote Murray’s report at length. His language, along with the images he conveys to us, merit our close attention:

"I was badly shocked by just how much weight my friend has lost, by the speed his hair has receded and by the appearance of premature and vastly accelerated ageing. He has a pronounced limp I have never seen before. Since his arrest he has lost over 15kg [33 lbs] in weight.

“But his physical appearance was not as shocking as his mental deterioration. When asked to give his name and date of birth, he struggled visibly over several seconds to recall both. . . .It was a real struggle for him to articulate the words and focus his train of thought. . . .Julian exhibited exactly the symptoms of a torture victim brought blinking into the light, particularly in terms of disorientation, confusion, and the real struggle to assert free will through the fog of learned helplessness.”

In his account of the court proceeding, Murray describes a perverse farrago of farce, travesty, and tragedy. This was railroaded injustice by any properly disinterested reckoning. Assange was confined in a glass enclosure the whole of the hearing — as he has been in all court appearances since. District judge Vanessa Baraitser, the presiding magistrate, ruled against Assange on each of the points his lawyers raised.

They requested additional time to prepare a defence, given that Belmarsh had deprived Assange of his records and restricted his meetings with attorneys. There would be no such extension. They argued that the extradition treaty between the US and Britain does not apply because it excludes political offences. There would be no consideration of the nature of Assange’s alleged crimes. A court in Madrid was at this time reviewing evidence that the CIA, through a Spanish company called UC Global, had spied on Assange while he resided with the Ecuadorians. Since this included occasions when Assange was conferring with his attorneys, a finding of guilt would be sufficient to nullify the extradition order: Baraitser took no interest in this self-evidently significant case.

I do not know how shocked one should be that we are able to watch as the United States and Britain abuse their power precisely to abuse Assange openly and without disguise

Five US government officials sat at the back of the courtroom. Prosecutors, led by Queen’s Counsel James Lewis, scurried to confer with them before responding to each point the defence raised. Baraitser then ruled according to the prosecution’s preferences. Here is Murray:

“At this stage it was unclear why we were sitting through this farce. The US government was dictating its instructions to Lewis, who was relaying those instructions to Baraitser, who was ruling them as her legal decision. . . . No one could sit there and believe they were in any part of a genuine legal process or that Baraitser was giving a moment’s consideration to the arguments of the defence. Her facial expressions on the few occasions she looked at the defence ranged from contempt through boredom to sarcasm. . . . It was very plain there was no genuine process of legal consideration. What we had was a naked demonstration of the power of the state, and a naked dictation of the proceedings by the Americans.”

Toward the end of his report, Murray offered a few details as to Assange’s circumstances at Belmarsh. These, too, should be of interest to us:

“He is kept in complete isolation 23 hours a day. He is permitted 45 minutes of exercise. If he has to be moved, they clear the corridors before he walks down them and they lock all cell doors to ensure he has no contact with any other prisoner outside the short and strictly supervised exercise period. . . .That the most gross abuse could be so open and undisguised is still a shock.”

He is kept in complete isolation 23 hours a day. He is permitted 45 minutes of exercise. If he has to be moved, they clear the corridors before he walks down them

There are, indeed, gross abuses galore in the fate of Julian Assange during this time, and since, certainly. These abuses have been by turns political, physical, psychological, and at last judicial. When preliminaries ended and formal extradition hearings began last February, Assange was again confined to an armoured glass box — unable to sit with his attorneys, unable to communicate with them while witnesses were called, with no access to the defence’s court papers, with no chance to speak — a muted spectator at his own hearing.

When Assange’s defence protested his preposterous confinement in a secure dock as if he were a dangerous criminal, Baraitser asserted (yet more preposterously) that Assange would have to post bail to be released from his glass confinement and sit with his lawyers. By this time, the court had psychiatric documents diagnosing Assange with clinical depression.

“I believe the Hannibal Lecter-style confinement of Assange,” Craig Murray (again present) wrote, “is a deliberate attempt to drive Julian to suicide.” There is something extreme in this conjecture, at least to the ordinarily democratic sensibility, but it is less so when considered against all that Assange could reveal — not least the grotesque and consequential fraud of Russiagate — once he is on American soil with little left to lose.

To be honest, I do not know how shocked one should be that we are able to watch as the US and Britain abuse their power precisely to abuse Assange openly and without disguise. While there was a remarkably prevalent news blackout in the months after Assange’s arrest, British and American authorities draw no curtain over the sorts of events I describe. What are we to make of this?

I believe the Hannibal Lecter-style confinement of Assange is a deliberate attempt to drive Julian to suicide

Vanessa Baraitser’s ostentatious condescension toward Assange gives us a striking and suggestive detail in this connection. Prosecutors acting for the crown but conferring in plain sight with American officials, indifferent to all legal propriety, give us another. It is often said that those who detain and try Assange intend to make an example of him — a flesh-and-blood warning to others who may attempt entrance into the empires of secrecy America and its allies operate within. This is certainly so, but it is not the whole of the case.

The rest of us, without ambitions to blow whistles or expose official wrongdoings, are also objects of the exercise. As Assange is disoriented, so are we to imagine ourselves. His confusion is intended to be our own. Baraitser condescends to us when she condescends to Assange and his attorneys. His struggle to assert free will is — but precisely — our struggle. In his learned helplessness — a psychiatric term coined by behaviourists to denote a coerced surrender to authority — we recognise our own. Assange’s totalised silence: again, it is to be ours. To gather these thoughts as one, we are meant to watch as the sovereign state demonstrates what the Assange case requires us to call limitless subordination. This phenomenon should not escape us.

“The arrest of Assange is scandalous in several respects,” Noam Chomsky writes in his contribution to In Defense of Julian Assange. “One of them is just the show of government power.” The linguist’s words are deceptively freighted for all their apparent simplicity. In them lies the irreducible meaning of Julian Assange’s fate. It is a question of purposeful display. What has become of power in the remnants of our democracies, the extent of its reach, what it guards at all costs, what it further aspires to, our relation to it: this is what we are meant to see.

The Origins of Totalitarianism is commonly read as a condemnation of the Nazi and Stalinist regimes, specifically as these found their most debased expression in concentration and extermination camps. This is fine but insufficient. We cannot underestimate the pertinence to our circumstances of Hannah Arendt’s tour-de-force exploration of what she termed “total domination”.

It is no good taking the camps or the systems that begot them as one-off aberrations to be excised from our understanding of history. This was Arendt’s very point in giving us an account of totalitarianism that reaches back to the 19th century. She persuasively establishes the phenomenon as part of the modern condition, and I do not know that we have left off being modern.

Arendt runs relentlessly and deep as she defines total domination in its fulsome specificities. Its intent is to strip humanity of all identity and individuation. It is to reduce all who are subjected to it to an interchangeable “bundle of reactions”, none in the slightest different from any other. Perfect predictability leads to perfect control. Here is Arendt on the means by which this is to be accomplished:

“Totalitarian domination attempts to achieve this through ideological indoctrination of the elite formations and through absolute terror in the camps. . . . The camps are meant not only to exterminate people and degrade human beings but also serve the ghastly experiment of eliminating, under scientifically controlled conditions, spontaneity itself as an expression of human behaviour and of transforming the human personality into a mere thing. . . so the experiment of total domination in the concentration camps depends on sealing off the latter against the world of all others, the world of the living in general.”

We will come to our indoctrinated elites shortly. For now let us remain with Arendt’s thought of absolute terror. How far must we travel from her idea to the learned helplessness Craig Murray detected when he saw Assange in the Westminster court for the first time since his incarceration at Belmarsh? How shall we understand the Assange in our three images, the Assange rendered barely articulate over his months at Belmarsh, as we watch Arendt’s acute mind at work? Certainly he has been sealed off against the world of all others. Do we witness — by glimpses, of course, our shards of pottery — a systematic effort to squeeze all spontaneity from him?

These questions are not difficult. Our replies require us merely to set aside the grim images of the camps we carry in our heads like frames in a grainy newsreel. Then, our minds clear, we must allow ourselves to think about convergences. History is our merciless but best guide. One of its bitterest lessons is the tendency of great powers to become what they stand against. The purportedly innocent are over time transformed into the guilty. The enemy of torture lapses into torture. The anti-imperial power becomes an empire. Hardly is the thought novel. It proves out almost invariably.

The purportedly innocent are over time transformed into the guilty. The enemy of torture lapses into torture. The anti-imperial power becomes an empire

“What is a camp, what is its juridico-political structure?” the philosopher Giorgio Agamben asks in Homo Sacer, a brief book he subtitles Sovereign Power and Bare Life. “This will lead us to regard the camp not as historical fact and an anomaly belonging to the past (even if still verifiable) but in some way as the hidden matrix of the political space in which we are still living.”

This is altogether bold on the Italian philosopher’s part. But as we shed our resistance to so startling a thought we read more clearly into what has become of Assange since his arrest. We can now recognise the purposeful extreme of his isolation — in prison but also from us, “the world of the living". No access to a computer, to his records, to (most of the time) a telephone: what is this if not an effort to obliterate identity to the extent possible, to strip away all spontaneity — which I take to mean autonomy, agency? What do we make of a man who struggles to say his name? In his helplessness do we see the previously robust doer of deeds reduced to a bundle of reactions?

Arendt does not seem to have explored how her discoveries might bear upon us now, we the living. But it is hardly too large a leap to think of Assange’s time at Belmarsh — such as we know of it — as an experiment of the kind Arendt so well investigated. At its sordid core, there is the same effort to dismantle the personality. It is this Assange wrote of when he told Gordon Dimmack he was unbroken but surrounded by murderers — murderers of the spirit as well as those around him charged with homicide, in my reading of his letter. From the first of the photographs considered earlier to the person Craig Murray saw standing before Judge Baraitser six months later, we have a record of his tragic regress toward the condition of “mere thing”. Borrowing from a scholar named Jon Pahl, let us call this innocent domination, the dominating power’s claim to virtue in its act of domination.

Since Assange’s first moments in captivity, when a half-dozen police officers carried him down the Ecuadorian Embassy’s steps, the corporeal dimension of the state’s conduct has been very plain. This we must also consider. If the project is total domination, it must begin with the body. It is through the body that the prisoner is deprived of all control. Guantánamo Bay, Abu Ghraib, the CIA’s secret torture sites, Chelsea Manning at Quantico and Leavenworth: there are many such cases, these merely the most readily to hand.

The excessive use of prolonged solitary confinement at “supermax” prisons across the US constitutes another. Bodily domination as a coldly efficient means of dehumanisation, of assault on all constituents of identity: from the time of the camps until today, it is always in evidence. This is what we look at when we look through the glass at Assange.

It would be illusory to posit that this use of the body is something new in the western democracies. Slavery, the American Indian campaigns, the Second world War internment camps: these are obvious precedents. But in this contemporary iteration we nonetheless find an unprecedented descent into convergences with some of the most detested features of the west’s 20th-century totalitarian adversaries.

We watch as our sovereign institutions, one after another, destroy themselves with illegitimate assertions of sovereignty. While once we looked to them for protection, we must now seek protection from them. This is the lesson Assange in captivity has for us

Routinised torture, the pervasive reach of surveillance into the spaces of daily life, lately the systematic punishment of innocent populations by means of diabolically calibrated sanctions, and now what amounts to the physical and mental abduction of those challenging the vast universes of sovereign secrets — all of this must concern us partly as a matter of morality but also because we are subject to it ourselves. We watch as our sovereign institutions, one after another, destroy themselves with illegitimate assertions of sovereignty. While once we looked to them for protection, we must now seek protection from them. This is the lesson Assange in captivity has for us.

Nowhere is this of graver consequence than in the case of our judiciaries. It is when judicial systems lapse that a society’s final fate becomes evident. Judges and courts are the last line of defense against “failing state” status. We must consider Baraitser’s imperious performance in this context. With her flagrant corruptions of due process and her high-handed demeanour, what is it she sought to convey, seated as she was in an English judge’s robe and peruke?

The relationship between law and lawgiver has preoccupied many a political philosopher over many centuries. In the modern west, where the citizenry is declared sovereign, those who make law and enforce law are assumed to be bound by law. It is difficult to think of Baraitser as a Cicero-reading legal scholar, but she nonetheless took a strong position as to the purview of law.

By word, gesture, and deed, she placed the giver of law outside the law. Those who consider this question in our time, Arendt and Agamben among them, define this as a “state of exception”. Sovereign power declares itself the exception to its own laws. This leaves the state inside and outside the judicial order at the same time, for it cannot be an exception unless there is a judicial order from which it is excepted. The sovereign extends law over the governed, in other words, so as to demonstrate its position above it. Agamben expresses the paradox this way: “I, the sovereign, who am outside the law, declare that there is nothing outside the law.” This is Baraitser’s implicit but very clear position: I, Judge Baraitser, embody the law and enforce it. I am not bound by the law I uphold.

“Everything is possible,” is among Arendt’s better-known interpretations of conditions in a totalitarian state. This, a state of exception par excellence, is the defining objective of total domination, she tells us. Arendt is writing about the sovereign’s claim to infinite prerogative, to put the point another way. Baraitser’s claim to sovereign prerogative is quite the same. Everything was possible in Baraitser’s courtroom — or, at the very least, no limit to the possible was tested. Are we not on notice that we all live within this condition? The sovereign can torture and it is not torture: Assange in captivity demonstrates this plainly enough. At the extreme — and the extreme has been reached numerous times in numerous cases — the sovereign can kill and it is not murder.

Not long after Julian Assange’s arrest, an organisation called Speak Up for Assange began circulating a petition asking journalists to support “an end to the legal campaign against [Assange] for the crime of revealing war crimes". The document is offered in eight languages. At writing it bears 1,400 signatures, mine among them, from 99 nations.

To gather 1,400 journalists on behalf of Assange is an excellent thing. But when we put this number against the number of journalists in the ninety-nine countries cited — there are more than 30,000 in America alone — we must draw a different conclusion. Where is everybody? we must ask. What happened (and when), such that the press that welcomed Assange and WikiLeaks after its founding in 2006 came to evince nearly rabid animosity toward both?

If 2010 marked WikiLeaks’ coming of age as a publisher, it was also the year the American press, along with media in Britain and elsewhere, began to turn on their former colleagues. The precipitating event was the October publication of “Iraq War Logs.” It was on this occasion that official Washington established three long-running themes: WikiLeaks risks American lives; WikiLeaks compromises national security; WikiLeaks aids those the United States deems adversaries. The American press concurrently began to shift its attention from the publications it had enthusiastically reproduced to WikiLeaks and its founder. Reports of internal dissent, financial difficulties, and Assange’s allegedly abrasive personality date to this time. An unrelenting campaign of character assassination had begun.

In the ensuing years the press and broadcasters have treated us to a truly preposterous list of Assange’s shortcomings, disorders, excesses, and perversities. He is a rapist, a narcissist, a megalomaniac, a fascist. He is a liar, he is unwashed, and he did not clean his bathroom at the Ecuadorian Embassy—where he mistreated his cat and smeared faeces on the walls. Caitlin Johnstone, the irreverent Australian commentator, gathered twenty-nine such entries and offers replies to them as her contribution to In Defense of Julian Assange. To read her list is to confront the extent to which American media have made a pitiful mockery of themselves, a juvenile spectacle worthy of Lord of the Flies. Entirely out the window, of course, is any further consideration of the war crimes and corruptions reported in “Iraq War Logs” and other releases.

On 13 April 2017, shortly after President Trump named him director of the CIA, Mike Pompeo addressed the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the Washington think tank. Pompeo devoted a remarkable proportion of his speech to WikiLeaks and Julian Assange. This reflects the timing of Pompeo’s CSIS presentation. Less than a year earlier, WikiLeaks had begun publishing mail stolen from the Democratic National Committee’s computer servers. By the time Pompeo spoke, the convoluted, devoid-of-evidence fable we call “Russiagate”—a cockeyed conspiracy theory if ever there was one—was fixed in the American consciousness. “It is time to call out WikiLeaks for what it really is—a non-state hostile intelligence service often abetted by state actors like Russia,” Pompeo asserted.

This was Pompeo’s essential message that day. The press and the broadcasters turned it into headlines, and another groundless bit of fabrication was on its way to being accepted as fact. The conjured connection with Russia was key. It licensed many in the press, and I would say most mainstream media, to abandon Assange, so finishing what it had begun years earlier: much that we find on Johnstone’s list of slurs dates from the time since Assange was identified as neither a journalist nor a publisher but as a foreign agent with some indeterminate tie to Moscow.

In Defense of Julian Assange gives us an excellent, well-edited record of a pilgrim’s progress as he fights our very necessary war against runaway secrecy in defence of properly democratic societies whose governments operate transparently. Daniel Ellsberg, Patrick Cockburn, John Pilger, and Matt Taibbi are among the book’s many distinguished contributors. Renata Avila, a Guatemalan human-rights lawyer who has represented Assange over many years, writes a cogent account of meeting Assange (in Budapest, 2008), during which he explained WikiLeaks’ working principles: decentralisation, security (of staff and documents), and protection of sources. Stefania Maurizi, an Italian journalist and longtime WikiLeaks collaborator, describes, albeit discreetly, the organisation’s operations from the inside out. There are repeated challenges to the by-now-baroque edifice of falsehoods erected to turn Julian Assange into one of the repellent malefactors of our time.

If In Defense of Julian Assange offers a factually sound understanding of the WikiLeaks founder and the truth-seeking tradition he stands within, it is also useful as a mirror to reflect upon the commonly accepted story of the man and his work. To read the book is to recognise that our corporate media’s over-the-top renderings of Assange are best understood as “persecution texts.” This term belongs to René Girard, the late philosopher and social critic. Persecution texts are accounts of transgressions told from the perspective of those persecuting the transgressor. They typically combine the real and the imaginary, the true and the false, and they are reliably replete with “characteristic distortions.” Of these distortions Girard tells us something very useful. Even if they are ridiculous (as in the Assange case), there is much to learn from them. The more ridiculous the text, Girard finds, the more it tells us about its authors. “The unreliable testimony of persecutors,” Girard writes, “reveals more because of its unconscious nature.”

Our question is clear. What do the very numerous persecution texts available to us reveal about the media that compose and publish them? It is not enough to see the pitiful and juvenile in press reports of scatological doings at the Ecuadorian Embassy, or of cruelty to a housecat, or of an unclean loo. These are texts. What do we find as we interpret them?

In the American context, our media have made Assange the object of a purification ritual. In this his persecution—and so I will call it—is in line with the Quaker hangings in Boston, 1659–1661, the Salem witch trials three decades later, the anti–Communist paranoia of the 1920s and 1950s, the Russophobia and Sinophobia that now beset us. In all such cases, the righteous community—transcendent, messianic, chosen—has been corrupted and must be regenerated, its purity restored. The polluting alien must be expelled. Hardly is it difficult to read this unconscious drive, primitive as it is, into our media’s obsessions with Assange the unclean, with Assange who is a Russian asset, with Assange who is not a journalist.

Girard would consider Assange a scapegoat in his highly developed use of this term. Assange in sequestered captivity is a sacred outcast, to put the point another way. This ever-perplexing figure has a history extending back to the Romans and has since inspired many interpretations and reinterpretations. The sacred outcast (homo sacer in Latin) is “noble and cursed,” in Girard’s phrase. He is considered worthy of veneration, but he is also a breaker of taboos and so is subversive of the established order. The admired transgressor: this will do as a thumbnail description to get us past a contradiction that is merely apparent, the holy man who must be cast out. By tradition the homo sacer, important to add, can be murdered without fear of retribution. This, too, is a feature of his fate.

The sacred outcast serves an essential function. In the time before he is ostracised, the threat of division, schism, or even violence hangs over the group to which his persecutors belong. A certain hysteria commonly besets the group during this crisis phase. Ejecting the homo sacer relieves these pressures. Differences within the group are dissipated. I will return shortly to this point.

Assange as archetype: we can gain much understanding if we use this thinking — judiciously, of course — further to illuminate the media’s treatment of him. If the righteous community has banished the transgressor from its midst, what was the transgression? In Defense of Julian Assange stands with the signature-seeking website on this point: Assange’s crime is to expose the crimes of the powerful. This is fine but not enough. The press and broadcasters have impurities of their own to bleach clean. What are these?

Assange the scapegoat has departed from the originary American code. This is his irreducible violation. He broke the taboo against questioning — prominently, in public space — the essential virtue of American intent and American power. Many of WikiLeaks’ major document releases challenge this sacrosanct precept. American media, with occasional and carefully attenuated exceptions, observe it, so staying well clear of the taboo. The originary code amounts to a code of silence at this point, so many are the instances of malign American conduct that go unreported (or dishonestly reported) by our corporate-owned newspapers and broadcasters. When Assange confronts the fallacy of American goodness and innocence, he also confronts the media’s sycophantic allegiance to official orthodoxies. In effect, he exposes the media’s culpability — its collaboration in preserving the myth necessary to obscure the true nature of American power.

How shall we understand those early years, when the press readily republished WikiLeaks releases? After the publication of “Iraq War Logs”, the New York Times set up an interactive site called “The War Logs”. It featured a search mechanism enabling readers to sift through the immense inventory of documents according to topic. This was diligent journalism in the new mode. Al Jazeera was the only other newspaper to match the Times for thoroughness. It is true that the Times concurrently published news reports that erased the complicity of US forces in the torture of Iraqi detainees, leaving readers to conclude the Iraqi military and police acted without the knowledge of American authorities. But the question remains: how did the press go from collegial collaboration with Julian Assange to scapegoating him as a pariah? It is a very curious journey by any measure.

American media, shelters of our indoctrinated elites, were fated from the first to face a choice in their relations with WikiLeaks and its founder. Sooner or later, working with the organisation was bound to put them at odds with the institutions of power they had long and loyally served. There was the potential for conflict, crisis, or both — schism or violence in the archetypal meaning of these terms. Sooner or later, they would have to decide whether to continue observing the originary code or to transcend it, as Assange had done to such impressive effect.

The moment to choose arrived with the release of “Iraq War Logs”. So did the disavowals and demonising begin — the casting out and scapegoating. And so was harmony restored between the press and the institutions of power it reports upon. It was inevitable that all the persecution texts would follow.

Now we come to the truth of our media’s remarkable animosity toward Assange. Journalism is seeing and saying; WikiLeaks and its founder are exemplary practitioners by this irreducible definition of the craft. The work is to see and say in the cleanest possible fashion — with gathered facts alone, without editorial comment, without persuasion.

In this way Assange stands as an ideal — never mind whether our corporate media so acknowledge him. In archetypal terms he is sacred. But Assange is also damned, for he is a traitor, just as he is accused. He is unfaithful to our mass media’s illusions, and we must consider these two ways. There are the illusions our press perpetuates in its pages, and of these there are of course very many. There are also the illusions media live within — illusions of integrity, of impeccable ethics, of principled independence from institutions of power. Mainstream media have long deceived themselves with these illusions, and it is these Assange betrays. He betrays, then, those who warrant betrayal.

So is Assange banished. So should we understand his banishment. Assange has preserved the lost ideals his persecutors recognise, with unconscious but legible bitterness, as no longer their own. It is by casting him out that the righteous community averts dangerous conflicts in its ranks and restores the existing order, the troubled peace Assange has so honourably disturbed.

Patrick Lawrence’s essay was written in response to ‘In Defense of Julian Assange’, edited by Tariq Ali and Margaret Kunstler, published by OR Books. This piece originally appeared in Raritan

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments