‘Everyone is an artist’: The entirely revolutionary Joseph Beuys

At the time, Beuys was a dreamer, a fantasist, and a bit weird, says William Cook. It’s only now, 100 years later, that his work finally makes sense

This summer, arts institutions all over Germany are celebrating the centenary of one of the strangest and most charismatic artists of the 20th century – a man who challenged the art establishment and changed the course of modern art. He was frequently dismissed as crazy, yet he transformed the cultural landscape – not only in his native Germany, but throughout the western world. His mantra, “Everyone is an artist”, became a cri de coeur for a new generation, for whom the gallery was just a sideshow. For Joseph Beuys, art could be anything – it encompassed everything, it had no limits. For him, being an artist was a state of mind, a way of life.

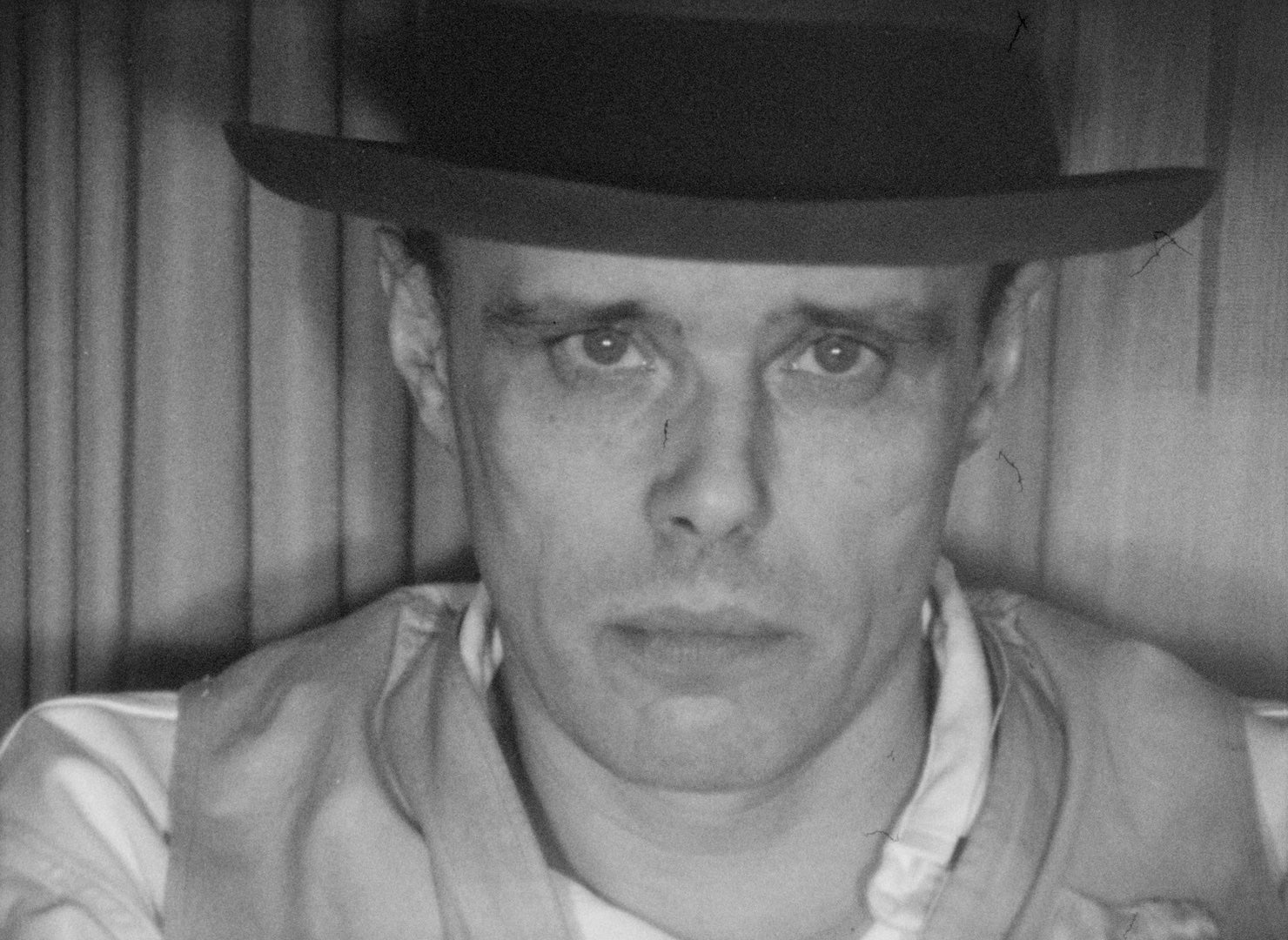

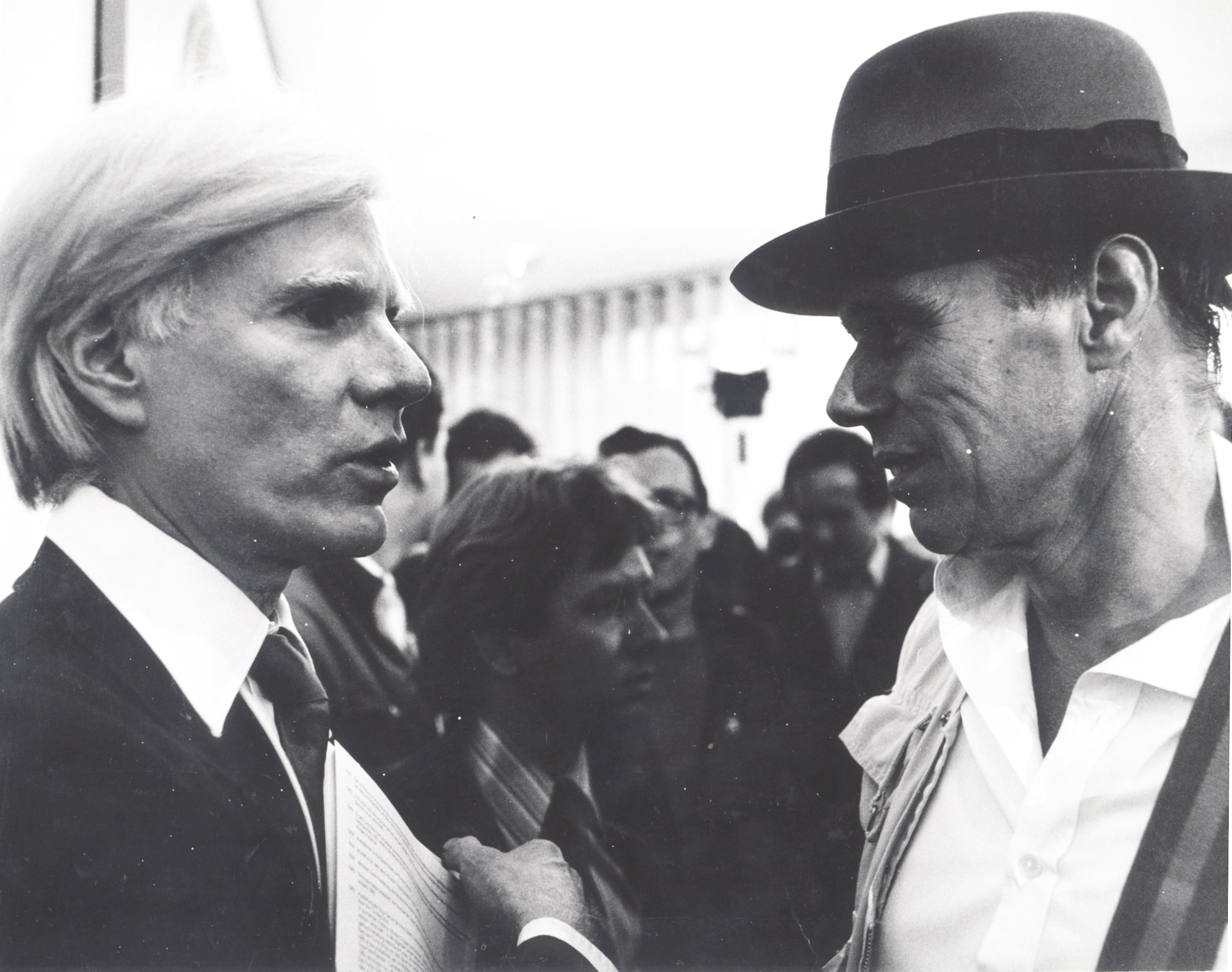

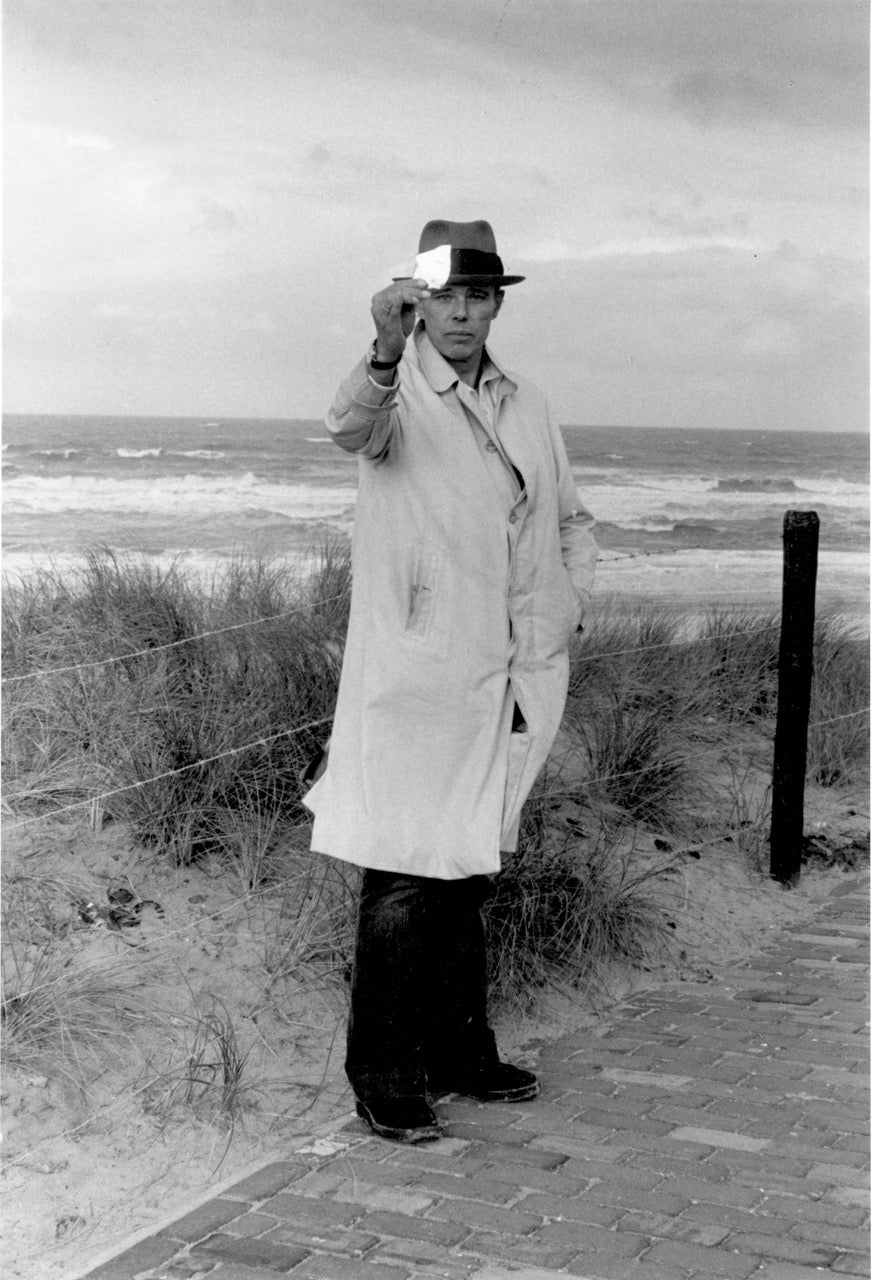

By the time he died in 1986, Beuys had come to be regarded as more of a living artwork than an artist – a kind of Teutonic Andy Warhol, instantly recognisable in his trademark uniform of fedora, fisherman’s tabard and fur coat. Some revered him as a shaman. Others denounced him as a charlatan. For some, he was a philosopher. For others, he was a holy fool, an idiot savant. So who was Joseph Beuys, and why is he still important? And what does he have to teach us about the world today?

Joseph Beuys was born 12 May 1921 in Krefeld, an industrial town near Düsseldorf, and raised in Kleve, a medieval town on the Lower Rhine. His father was a moderately successful businessman. He was an only child. He was 11 years old when Hitler came to power. In 1936, like most boys his age, he joined the Hitler Youth. He was an able student, with a flair for drawing and an interest in science. He was unsure whether to train as a sculptor or a doctor. And then, when he was 18, Germany went to war.

Beuys volunteered for the Luftwaffe, and was sent to the Crimea, where he served as a rear gunner in a Stuka squadron. In 1944, his plane was shot down in no man’s land. Beuys was badly injured. The rest of the crew were killed. These facts are undisputed. What followed became a matter of fierce controversy. Beuys said he was rescued by Tartar tribesmen, who nursed him back to health. To keep him warm and heal his wounds, they wrapped his broken body in fat and felt – two materials which featured prominently in his subsequent artworks. It was a profound and moving tale of resurrection and redemption – a shame it wasn’t true. Beuys was the sole survivor of the crash, which left him badly injured, but he was rescued by the Wehrmacht and taken to a field hospital. It was the Nazis who saved his life, not the Tartars. His salvation was a fabrication – a romantic, atavistic fantasy.

This discrepancy only came to light after Beuys became famous, and was seized on by his detractors as proof that his public persona was a sham. Yet Beuys told this story countless times and seemed to believe every word of it. So was the whole thing a delusion, a form of post-traumatic stress disorder? Had his head injury left him brain damaged, or affected his memory? Or had he simply told the story so many times he’d convinced himself it was true? For his critics, this proved he was a madman or a mountebank, but for Beuys this wasn’t fraud, it was fiction. To escape the nightmare of the Third Reich and the Holocaust, he’d turned his life into a work of art.

After the Second World War, Beuys enrolled at the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie, one of Germany’s most prestigious art schools. It was a hard time to be an art student in West Germany, but a creative era too. Occupied by foreign forces, its cities reduced to rubble, Germany lay in ruins – disgraced, devastated and divided – and yet anything was possible. A man like Beuys could reinvent himself. Everything had been swept away.

Beuys revelled in this brave new world. He spent seven years as a student, finally graduating in 1953. His work was well-regarded, but he struggled to make a living. He was rescued from penury in 1961, when the Kunstakademie made him professor of monumental sculpture. Ironically, this post had been created during the Third Reich, when sculptors were confined to crafting colossal statues of Aryan supermen. Beuys’ reinterpretation of this genre could scarcely have been more different. “He takes a step back and thinks about the concept of art,” says Dr Ludger Schwarte, professor of philosophy at the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie. “He is entirely revolutionary in his artistic practice.”

Beuys had a great talent for creating striking artworks out of everyday objects. The meaning of these works was opaque, but they packed a powerful punch – sometimes haunting, sometimes humorous, often a bit of both. His Trans-Siberian Express was a reversed canvas, turned towards the gallery wall, nailed into the plasterwork, so you couldn’t see what (or even if) he’d painted on it. A Rose for Direct Democracy comprised a single rose suspended in a scientific beaker. The Pack consisted of 24 sledges spilling out of the back of a Volkswagen camper van, like a pack of huskies. Each sledge was equipped with a felt roll, a lump of fat and a torch. “The imagery he uses is mysterious,” says Dr Catherine Nichols, co-director of the centenary festival, Beuys 2021. “It captivates some people, and it alienates others.” Yet although his work was cryptic, it was dynamic – closer to pop culture than fine art. “The laughter of the Beatles counts for more than the appreciation of Marcel Duchamp,” he said.

These enigmatic artworks were greeted with a good deal of antipathy, but the thing that really got people riled were his Aktions, the term he used for his bizarre performances. In one of these Aktions, in Aachen in 1964, he was assaulted by an indignant student, leaving him with a bloody nose. In the aftermath of this attack Beuys was photographed, angry and defiant, his face smeared with blood, holding a crucifix in one hand, like a priest performing an exorcism, the other arm raised high in some sort of salute. What did it all mean? God knows, but it was an arresting, disturbing image. It was this snapshot which made him famous. Beuys had arrived.

In 1965, Beuys performed an even stranger Aktion called How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare. For several hours he sat in the window of an art gallery in Düsseldorf, his face coated in honey and covered with gold leaf, cradling a dead hare in his arms, talking to the animal about art. There was no access to the gallery. A large crowd gathered in the street outside. The meaning of this artwork was elusive. A lot of folk thought it was nonsense, but no-one could call it dull. “It has to be sensational,” he said, “Otherwise, it’s of no interest.” His art was esoteric, but he knew how to cause a stir.

There was a messianic aspect to his performance art which some people found infuriating. In some of his public pronouncements he sounded less like an artist or an academic, more like the leader of a religious cult. He told students he would set them free. He sometimes even washed their feet. “He plays the Messiah,” wrote the German sculptor Norbert Kricke in Die Zeit, one of Germany’s leading national newspapers. “He wants to convert us. He wants the academy to take over the role of the church.”

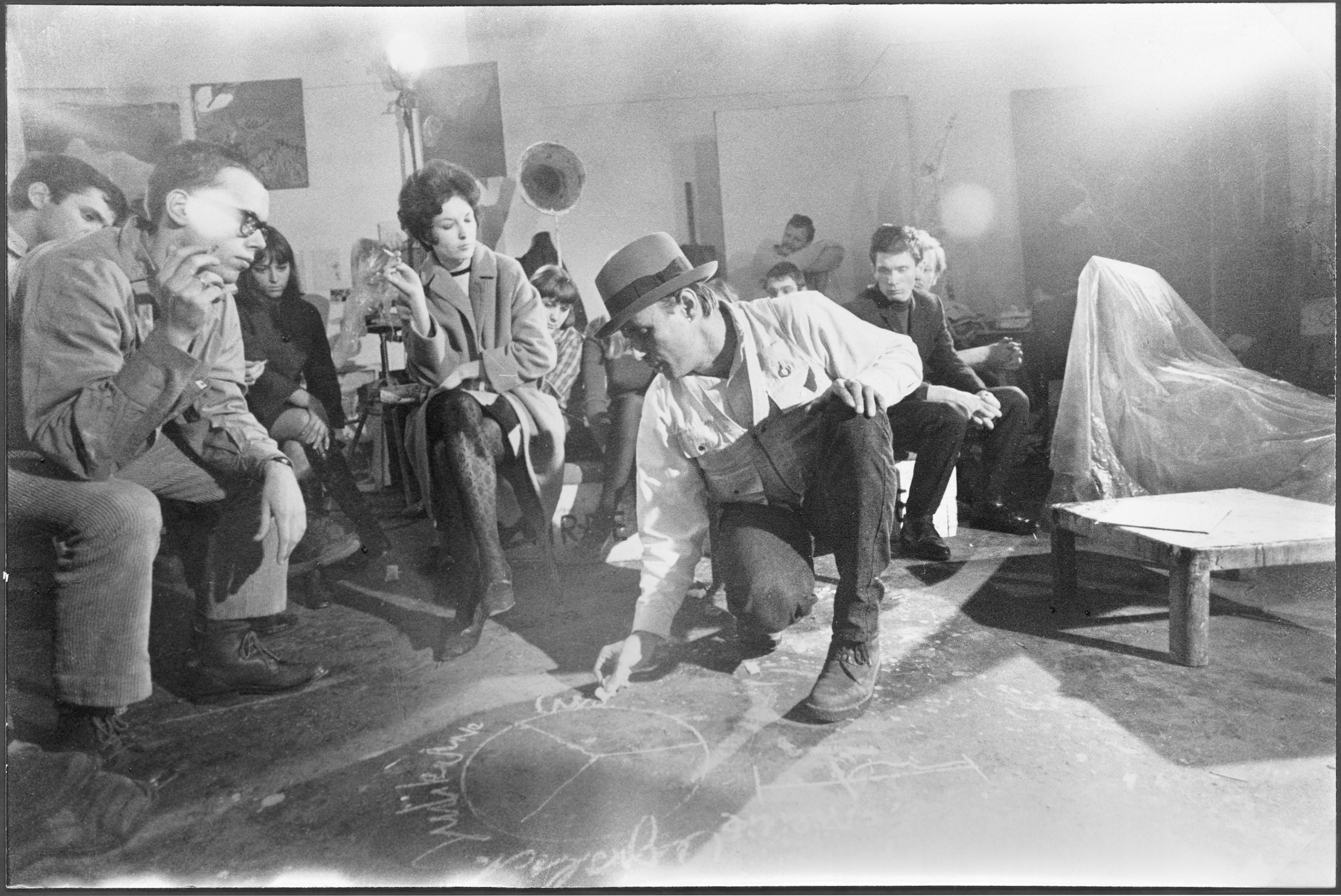

Beuys’ professorship gave him a steady income and the freedom to make the art he wanted, but unlike a lot of lecturers he never saw teaching as a chore. “Every human being can be creative if they are given the opportunity to be creative,” he said. “Teaching is my greatest work of art.” He was a stimulating pedagogue who had a liberating influence on his students, but his style was eccentric – to say the least. At a matriculation ceremony in 1967, before an audience of (self) important bigwigs, he got up to make a speech and spent several minutes grunting and roaring like a wild, wounded beast (”doubtless one of the things held against me years later, when I was dismissed”). “Professor barks into microphone” ran the headline in the local paper. It sounds hilarious, but no one found it funny at the time. It was far too frightening. There was no laughter in the auditorium, only silence. Here was a man on the edge of sanity, more like a tortured animal than a rational human being.

Yet there was a method in his madness. He was a stickler for punctuality and stressed the importance of life drawing. It was his admissions policy, more than anything, which put him at loggerheads with the authorities. Beuys believed that anyone who wanted to study art should be allowed to do so (he said the applicants with the worst portfolios often turned out to be the best students). The idea that a professor should decide which candidate deserved a place, and which ones didn’t, was an affront to everything he held sacred. His superiors did not share his point of view. In 1971, he staged a sit-in with 54 rejected applicants. In 1973, he was dismissed.

For Beuys, being kicked out of the Kunstakademie was a blessing in disguise. With no local stipend to sustain him, his art became international. In 1978 he was reinstated, but it’s telling that he did some of his best work during the nomadic years in between. In 1974 he was invited to New York, but he’d vowed never to set foot in America so long as US troops remained in Vietnam. His idiosyncratic solution to this problem was an Aktion called I Like America And America Likes Me, in which he was transported from JFK airport to a New York gallery in an ambulance, on a stretcher, and left in the empty gallery with a wild coyote and a pile of copies of The Wall Street Journal. For three days, Beuys and the coyote inhabited the same space, watched by a bemused crowd outside. After three days Beuys was put back on the stretcher, put back into the ambulance, and taken back to JFK. From there he flew back to Germany, having never actually set foot on American soil.

Art critics interpreted this Aktion as a critique of capitalism and imperialism (the coyote is indigenous to North America, revered by Native Americans, and eradicated by invading Europeans, who saw it as a pest). I prefer to think of it this way: if you were walking through Manhattan, past rows and rows of shop windows, laden with all sorts of consumer tat, imagine how this image would make you stop and stare, and think again about the world you live in. Would window shopping ever seem the same again?

These Aktions took performance art into uncharted territory, but Beuys now required an even bigger arena for his ideas. With a group of like-minded artists and intellectuals, he founded the Free International University as a roaming forum for debate. At the Edinburgh Festival, he gave a 12-hour lecture, from noon until midnight. “He was a man of towering intellect,” said Richard Demarco, the innovative Scottish gallerist who brought Beuys to Edinburgh numerous times during the 1970s. “He was, for me, the Leonardo da Vinci of the 20th century. I hadn’t the faintest idea what he was doing, but I knew it was the most important thing I’d ever seen.”

During the 1970s, Beuys became increasingly involved in politics. He was a leading light in the German Student Party and the Organisation for Direct Democracy, but his most significant achievement was as one of the founders of Germany’s pioneering Green Party. The party never adopted him as an official candidate (his anarchic philosophy was far too radical, even for them) but in the early days, when this new party was virtually unknown, his high-profile campaigning gave it an invaluable boost. “You cannot tell the story of the Greens without his contribution,” says Professor Schwarte.

Beuys’ passionate commitment to ecology reached its apotheosis in his most beautiful and powerful artwork, 7,000 Oaks. Invited to make a sculpture for Documenta, a contemporary art festival in the German city of Kassel, in 1982, Beuys deposited a huge pile of 7,000 basalt obelisks in the city’s central park. Each time someone contributed towards the cost of this immense artwork, Beuys planted an oak tree in Kassel and erected one of these obelisks beside it. “The tree is an element of regeneration which in itself is a concept of time,” he explained. “The tree keeps growing taller. The rock stays as it is.” Thousands of individuals and institutions chipped in, and as the pile of obelisks shrank, Kassel became a forest. A historic city destroyed during the Second World War, and rebuilt in bland modernist style, Kassel has been rejuvenated by these majestic trees, and the artwork is still evolving. At first, the obelisks dwarfed these saplings – but as the trees have grown and grown, the obelisks have shrunk. Forty years on, the trees look huge, and the obelisks look tiny. Just imagine what they’ll look like 100 years, 400 years from now. As Richard Demarco observed, Warhol turned art into money – Beuys turned art into love. “I am not a gardener who plants trees because trees are beautiful,” he said. “Today, trees are more intelligent than people.”

Beuys didn’t live to see the completion of 7,000 Oaks. He died of heart failure in 1986, aged 64. A heavy smoker and a workaholic, he’d always driven himself very hard. “For me, there’s no weekend,” he said. “You have to wear yourself out. You have to burn yourself down to ashes, otherwise there’s no point.” In spite of his iconic status, friends remember him as warm and approachable, with a lively sense of humour – always able to see the funny side, always interested in what other people had to say. In stark contrast to his public image, his private life was conventional, even bourgeois – happily married with two children, the archetypal family man. “He was rather modest – you could count on him,” says Carl Friedrich Schröer, a journalist who grew up in Düsseldorf, and got to know Beuys as a teenage student. “He was not a star.”

During his lifetime, Beuys was mocked and derided as a hopeless idealist. Today, it’s remarkable how many of his concepts have become mainstream. His environmental concerns now look especially prophetic. He would have felt perfectly at home in current movements like Extinction Rebellion. He was way ahead of his time regarding animal rights. Today his German Green Party stands on the brink of government. Campaigners like Greta Thunberg carry his environmentalist message around the world. “Each one of us has creative potential which is hidden by competitiveness, success and aggression,” he declared. “Environmental pollution runs parallel with the pollution of the world within us. Hope is denounced as utopian and discarded hope breeds violence.” He believed money was a corrupting force, a poison flowing through society like poison flowing through the human bloodstream. “There is an important strand in his work which has to do with compassion,” says Professor Schwarte. “The suffering of animals, the suffering of human beings.”

Sure, he could be difficult, but so are lots of innovators. Sure, a lot of the things he did seemed absurd, but he left behind some astonishing artworks and an abundance of bold ideas. He dared to imagine the world he wished to live in, and did his utmost to create it, and in doing so he inspired an army of artists and activists. “Art, for me, is the science of freedom,” he said. Happy 100th birthday, Joseph Beuys. At the time, you seemed like a dreamer and a fantasist. Now your ideas make a lot more sense.

For more information about Joseph Beuys centenary events in Düsseldorf and elsewhere, visit beuys2021.de

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments