Japanese pop culture’s complicated history with Hollywood

With the release of Netflix’s remake of ‘Cowboy Bebop’, Jim Moore takes a closer look at why the thirst for live-action adaptations of animated originals hasn’t always worked out

Japanese pop culture is mounting a sustained assault on the global stage. A string of its top properties are set for live-action adaptations as Hollywood, and its streaming giants, seek to satisfy their insatiable desire for new and exciting content; for stories that can stand out and draw eyes in an increasingly competitive field

Netflix’s hotly anticipated live-action adaptation of Cowboy Bebop, the legendary anime, is out now – and there’s plenty more where that came from.

Legendary Entertainment, which has enjoyed success with Detective Pikachu, Pacific Rim and several Godzilla films and is fresh from Dune, is working on a My Hero Academia movie. Netflix will follow Cowboy Bebop with a series based on One Piece, the oddball pirate manga and anime that boasts a large and devoted fanbase.

A movie based on the venerable Gundam franchise is also in the works.

Lovers of manga and anime in their original forms have good reason to view this explosion of adaptation with both excitement and a certain amount of trepidation.

Western takes on beloved Japanese originals haven’t always worked out so well.

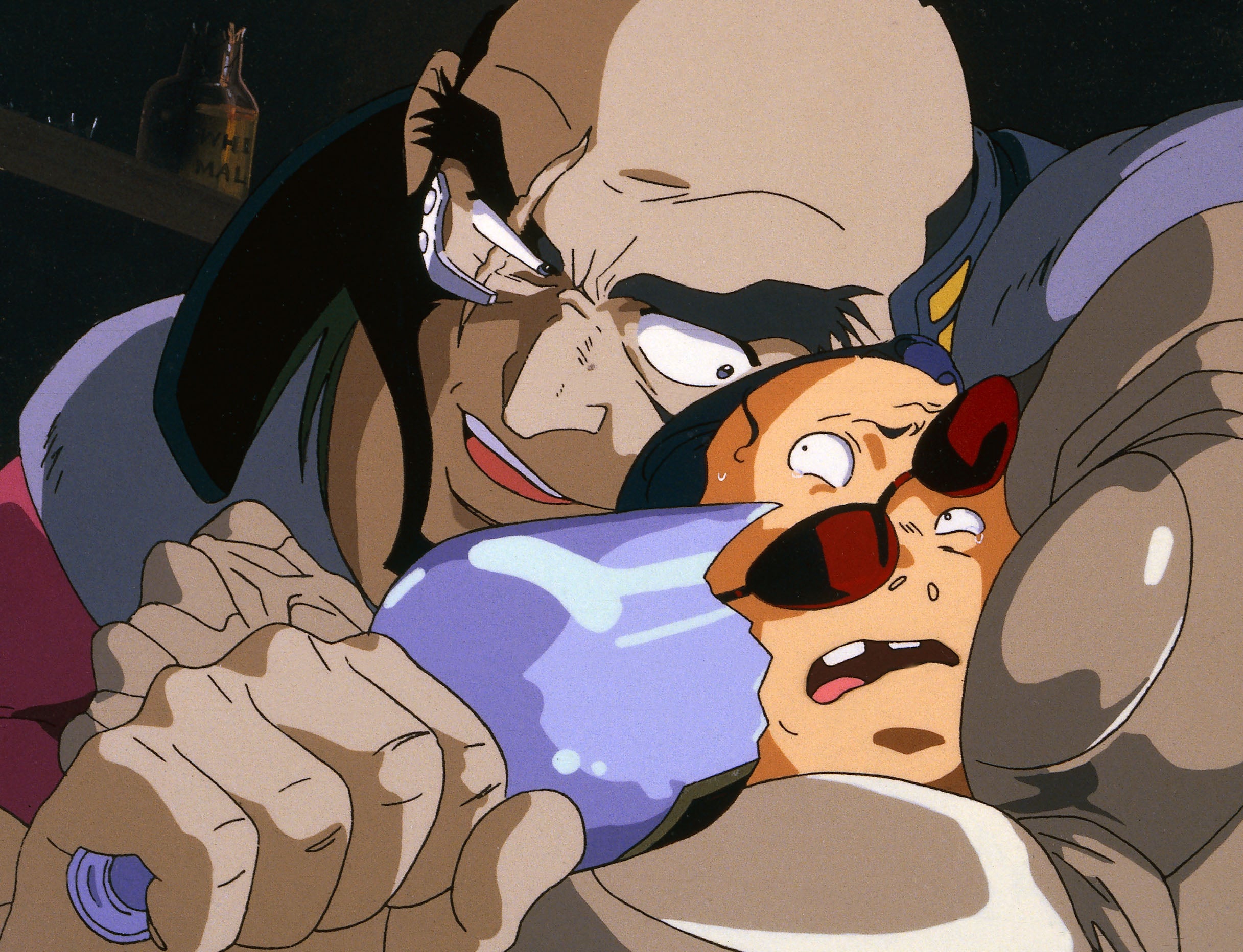

The likes of Death Note, Ghost in the Shell, and especially Dragon Ball, have all crashed and burned as either live-action movies or series.

To be fair, this isn’t just true of manga and anime. Western remakes of Japanese films generally have proved decidedly shaky. With the possible exception of The Ring, featuring Naomi Watts, name a J-horror that has worked out well, let alone come close to the original, when taken across the Pacific Ocean.

Cowboy Bebop may be different. The trailers suggest it has retained the retro Seventies look of the genre splicing anime, which puts sci-fi, film noir, westerns and crime into a pot and stirs them up produce a wildly entertaining stew.

Set in a future after an unspecified accident with a hyperspace gate has wrecked the Earth, with civilisation moving out into the solar system, the set-up looks dystopian but it really isn’t. It’s more a future in which the problems are quite similar to the ones we have today. Uniquely, there is no Star Wars-style scene setting intro text or voice over. It plays out as if we are watching in that future.

The viewer is asked to pick up the background as the show moves along. It’s a master of what countless creative writing teachers have tried to instil in their students: show don’t tell. And it has more style in the intro than some shows have through their entire runs.

The genesis of the original is a story in itself. Creator Shinichiro Watanabe was basically told he could do what he wanted with the project just so long as he delivered an anime with spaceships that Bandai could sell as toys.

‘Cowboy Bebop’ consistently sells thousands of units every year in the UK without any real push

The result featured crime syndicates, bounty hunters, gunplay, doomed romance and, in the first episode, a drug called “bloody eye” that causes bloody mayhem. It duly caused consternation among its sponsors, and its first run in its home market, with a 6pm time slot, omitted the majority of the episodes.

But while its sponsors may have been horrified, it was tailor made for a cult fanbase, including anime’s growing western fanbase, which had been given a major shot in the arm with the release of Akira several years earlier. It connected with that fanbase in a big way.

When Andrew Partridge, the CEO of Anime Ltd, produced an ultimate Blu-ray edition, lovingly packaged in a vinyl flight case – there’s that style again – with multiple extras, it was sold at £300, although it was available for £225 to those who got in early.

Despite the ambitious, even prohibitive, price point, the 1,000-strong run sold out in double quick time and it has since appreciated in value.

“Cowboy Bebop consistently sells thousands of units every year in the UK without any real push,” says Partridge. “There’s a whole new audience every year discovering it. I think they’re in for a treat. And this will take it well beyond that community.”

But the sort of passionate, engaged fanbase the show has ready made can cause trouble for a project if it fails to hit the right note, as many animes adaptations haven’t.

Cowboy Bebop will have to satisfy high expectations.

Leah Holmes, a former journalist turned academic specialising in anime fandom, however, says it has an important advantage over some of the past failures.

“A lot of the western adaptations of anime, manga and Asian cinema generally, they fail to translate when producers try to westernise them. They lose the cultural context that makes them successful. That’s not such a problem with Cowboy Bebop. Its backdrop is quite diverse. Its themes are universal. When it came out it was incredibility popular. It had a great deal of crossover appeal. It shouldn’t run into the same problems as, say, Death Note.”

The latter is a horror/crime manga and anime that follows the adventures of a teenaged genius who comes across a book that grants the user the power to kill anyone named in its pages. It made a successful translation to a live-action format in Japan but even the formidable presence of Willem Dafoe couldn’t save the western version, which has a dismal 38 per cent rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

“The various Japanese films made were decent but so much of what ties it together is to do with Japanese society and attitudes towards crime and the police and social responsibility that it just did not translate,” Holmes argues.

She contrasts this with Detective Pikachu, which could easily have crashed and burned but performed well at the box office and even won round a majority of the critics despite a somewhat convoluted plot.

The presence of Ryan Reynolds, and an irreverent tone that led to it being described as “Deadpool for kids”, didn’t hurt.

“Detective Pikachu could have gone so terribly wrong but in the end it worked out very well. Everyone seemed to be having a good time with it and you could tell Ryan Reynolds was loving it,” says Holmes. “But this is now one of the world’s biggest media franchises. It has no real geographic footprint. You can very easily transplant it.”

Holmes says Ghost in the Shell is another example of a more culturally grounded property that fails to cross over as a live-action Hollywood offering.

It caused itself a problem at the outset by casting Scarlett Johansson as the very Japanese Major Motoko Kusanagi, the central character.

“For so long, Hollywood and the people who have defined storytelling in America, have defined it as stories to be told for and by white people,” Trevor Noah, host of the Daily Show said in a measured and thoughtful monologue.

“And all people are saying is, if there are these opportunities where it's like, a Japanese character pops up… you saw how many people loved Crazy Rich Asians ’cause they’re like, ‘hey man, just to see myself on screen’ – not in just a stereotypical fashion but just to see myself as a human being’.”

It wasn’t only the regrettable whitewashing of the lead role that created a problem.

The anime, hugely influential with western filmmakers, is set in a cyber punk future Japan, full of political intrigue and social tension. It’s dense and philosophical, sometimes head spinning. Much of that was stripped out of the film, presumably for fear western audiences wouldn’t take to it. Except that a sizeable western audience had taken to it via the anime. And a western audience took to the Matrix, which is also dense and philosophical and head spinning, and was very obviously influenced by Ghost.

Josh Stevens, a writer on anime, says: “I think Leah makes a really good point about Cowboy Bebop being a very unique type of show. There aren’t the cultural barriers to adapting that sort of story as there are with some properties. I’m not as down on Ghost as some people. It’s a very good looking sci-fi film. It’s just not a very good Ghost in the Shell film.”

Stevens admits that he struggles to find a favourite among the anime adaptations that have appeared to date, and found Death Note so bad he actually laughed.

“I’ve never done that with a film before. But I do think that even the ones that were misfires have things that they got right. I might have laughed at how bad Death Note was overall, but Willem Dafoe was inspired casting as the Shinigami Ryuk.”

If the series does nothing more than get Yoko Kanno’s foot in the door of the boys’ club of Hollywood composers, it will have served a noble purpose

The struggle that makers of films and shows have in grappling with Japanese themes that western anime audiences have no problem with, could pose an issue for My Hero Academia.

Set in a world where the majority of the populace have some level of special ability, it focusses on a group students seeking to become qualified heroes. The ones with the really knock out powers.

Its conception of superheroes is starkly different to the American one that has become a pop culture staple. They’re typically vigilantes who often have strained relationships with government, a theme explored in Captain America: Civil War.

In My Hero, by contrast, the heroes are public servants.

Stevens identifies another potential challenge for the makers: “One of the big issues with live-action anime adaptations is that a lot of characters can end up appearing like caricatures. That puts a lot on the acting. Then there’s the look of them. You can do so much with the look of a character in anime but when you try and move it across it can end up looking cheesy. That was the problem with the live-action Japanese adaptation of Full Metal Alchemist.

“Remember, in the early X Men adaptations they had Wolverine just wear black, rather than spandex like in the comics. That was smart.”

As for One Piece, which has produced umpteen mangas, animes, and anime movies, Holmes says: “I think the biggest thing standing in its way, is that it’s just so bonkers. It’s not the most surreal anime I’ve ever seen but it has a very particular kind of vibe.”

Holmes may have a point. Pirates are a risky proposition at the best of times, as repeated Hollywood flops (Hook, Cutthroat Island) have proved.

One Piece also features a lead character who can stretch his limbs at will. “I’m not sure how they’ll get that to work on screen,” says Holmes. “But they have the original creator working on it and they’ve cast some good people.

“In essence, what makes a good adaptation is the creators knowing what they are doing and understanding what they have; in understanding what makes the original tick.”

That is something they have clearly struggled with when it comes to anime. But maybe they can learn from past mistakes.

The live-action Bebop’s creators certainly appear to have understood what they had, at least so far as the look of the show goes. They also have Yoko Kanno on board, which is a big plus point. Her intoxicating score, which fused a diverse mix of musical genres, borrowing from soul, funk, jazz and more besides, was a key part of the anime’s success.

If the series does nothing more than get her foot in the door of the boys’ club of Hollywood composers, it will have served a noble purpose.

Says Partridge, who has produced a fresh special Blu-ray edition to coincide with the series’ launch: “Cowboy Bebop has an international feel. It has a gripping story. It’s irreverent. It takes itself seriously when it needs to but it’s not afraid to have a laugh. Honestly, however it turns out it’s a good thing. It will grow the audience for the anime. But I’m hopeful.”

If Bebop connects with a wide audience, perhaps it can show others the way. Just as the anime did.

See you, space cowboy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

4Comments