Can we ever really know what historical figures looked like?

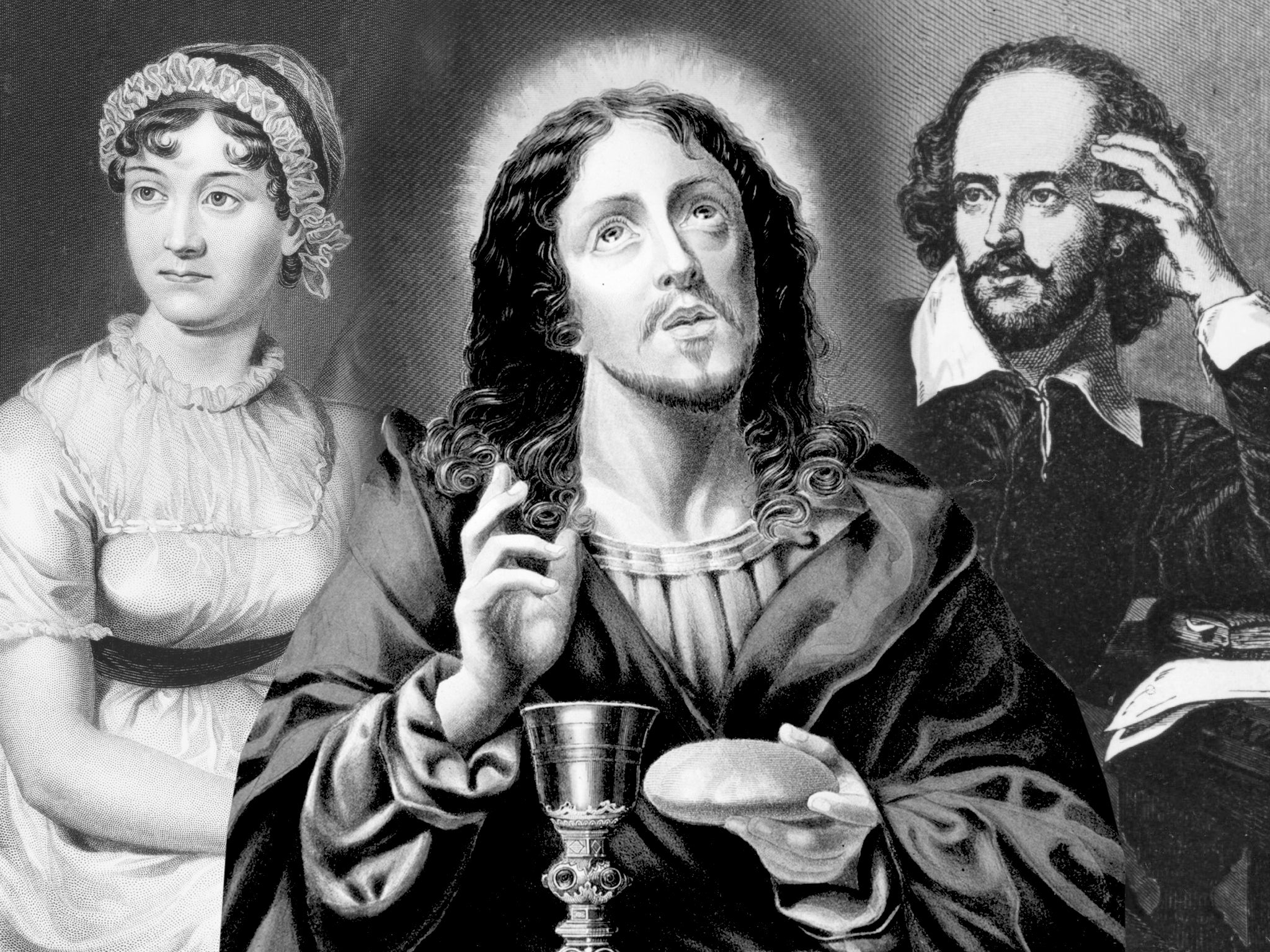

What face do you see when you think of Jane Austen or Shakespeare? We might have images of these figures in our heads, derived from paintings, but what did they really look like, asks David Lister

The Holburne Museum in Bath is this month mounting an exhibition around just one picture. The picture is a sketch of a woman who lived literally across the road from the museum, and it was drawn by her sister. OK, there’s a bit more to it than that. The picture is of Jane Austen, and the sketch by the novelist’s sister, Cassandra, is acknowledged to be the only accepted depiction of Austen. Arms folded and a little impatient-looking, the picture has adorned innumerable book covers, and when her name is mentioned, this is the image we immediately conjure up. And, of course, it is now the image on the £10 note.

But is this picture, on loan from the National Portrait Gallery, a true likeness of Austen. The truth – whisper it softly around the museum and the NPG – is that we have no idea. For a start, Cassandra may have wished to flatter her sister and make her a little more attractive than she was. It’s equally possible that there was a bit of sibling rivalry at play, and Jane received a sterner persona than she displayed to the world. Also, was Cassandra even any good? Did she have the ability to sketch a true likeness? She has no real reputation as an artist beyond this one picture.

To add to the mystery, the sketch about to go on show in Bath, unsigned and unfinished, is also undated and unrecorded in the correspondence between the two sisters. After Austen’s death, her reputation grew, as did demand for a reliable portrait. Cassandra’s sketch was turned into an engraving, which Austen’s niece, Caroline, said depicted a “pleasing countenance”, crucially adding, “though the general resemblance is not strong”.

So, there we have it. Austen’s own niece said it wasn’t much of a likeness. Prettified, perhaps, idealised perhaps, it’s how every reader of her work, and every handler of a £10 note, will choose to think of her.

Does it matter if we know what she looks like or not? Yes, says Austen expert David Lassman, former director of the International Jane Austen Festival. Writing for History Extra in 2017, he said: “The fact that her works continue to be so immensely popular worldwide, both in their written form and numerous screen adaptations, and the fact that the commercial industry that has sprung up around her is worth billions of pounds, we might, at the very least, be curious to find out if the likeness we are presented with owes more to marketing than actuality.

“In the 200 years since Austen’s death, images purporting to be of her have been made-over, touched up, sexed up and prettified in order to advertise everything from books and alcohol to magazines and cosmetics.”

The exhibition’s Spanish-born curator, Monserrat Pis Marcos, describes the picture as “this fragile and iconic portrait of one of the most important figures in English literature, and one of Bath’s most famous residents”. But she agrees that we don’t really know if it is what Austen really looked like.”

But in truth, like Jane Austen, like Dante, our own national poet and playwright is another whose likeness we take for granted, whereas in fact we simply don’t know for sure what he looked like

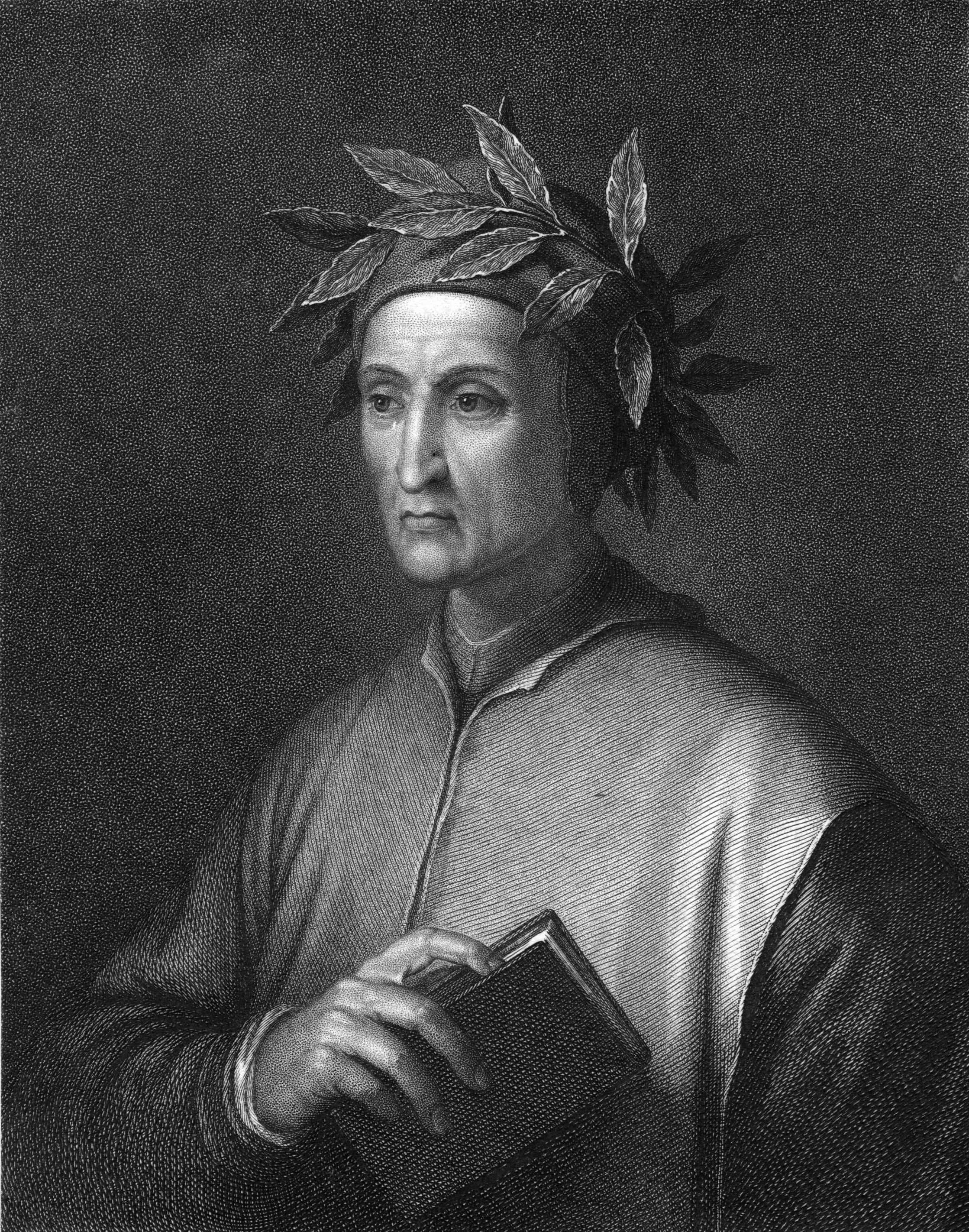

She makes the comparison with Dante, another iconic figure in world literature, whom we think of automatically as the man with the aquiline nose. The father of the Italian language and author of the greatest epic poem of the Middle Ages, the Divine Comedy, had no portraits made of him in his lifetime. Most were painted at least a year after his death, and the most familiar, gaunt and stern with striking long, hooked nose, 170 years after his death in 1321. It took nearly another 700 years for research on his skull at the University of Bologna to determine that his nose was probably pudgy like a pugilist.

Professor Giorgio Gruppioni, the anthropologist who led the project in 2007, told the BBC: “We all had our ideas of what Dante looked like. But if this is right, it shows his face was quite different from what we envisaged.” The classical portraits of his were described by Professor Gruppioni as “psychological renditions”, impressions that artists had formed of Dante from readings of his work.

Ah, those psychological renditions. Make the man or woman fit the work. It suits us as we gaze at a Jane Austen book cover or a £10 note to see a face that is knowing, perceptive, impatient and maybe just a touch acerbic. Just as it suits us to see Shakespeare in that portrait familiar round the world as the great thinker and noble mind. The face, surely, should reflect the writing.

But in truth, like Austen, like Dante, our own national poet and playwright is another whose likeness we take for granted, whereas in fact we simply don’t know for sure what he looked like.

We think we do. We can all picture the middle-aged man with receding hairline, thin moustache and wavy hair with his Elizabethan ruff. What we recall is the black and white engraving that was the frontispiece of the first folio. It was produced by the Flemish engraver Martin Droeshout in 1623, and not published until some years after the Bard’s death. It was probably copied from a portrait of Shakespeare that has not survived.

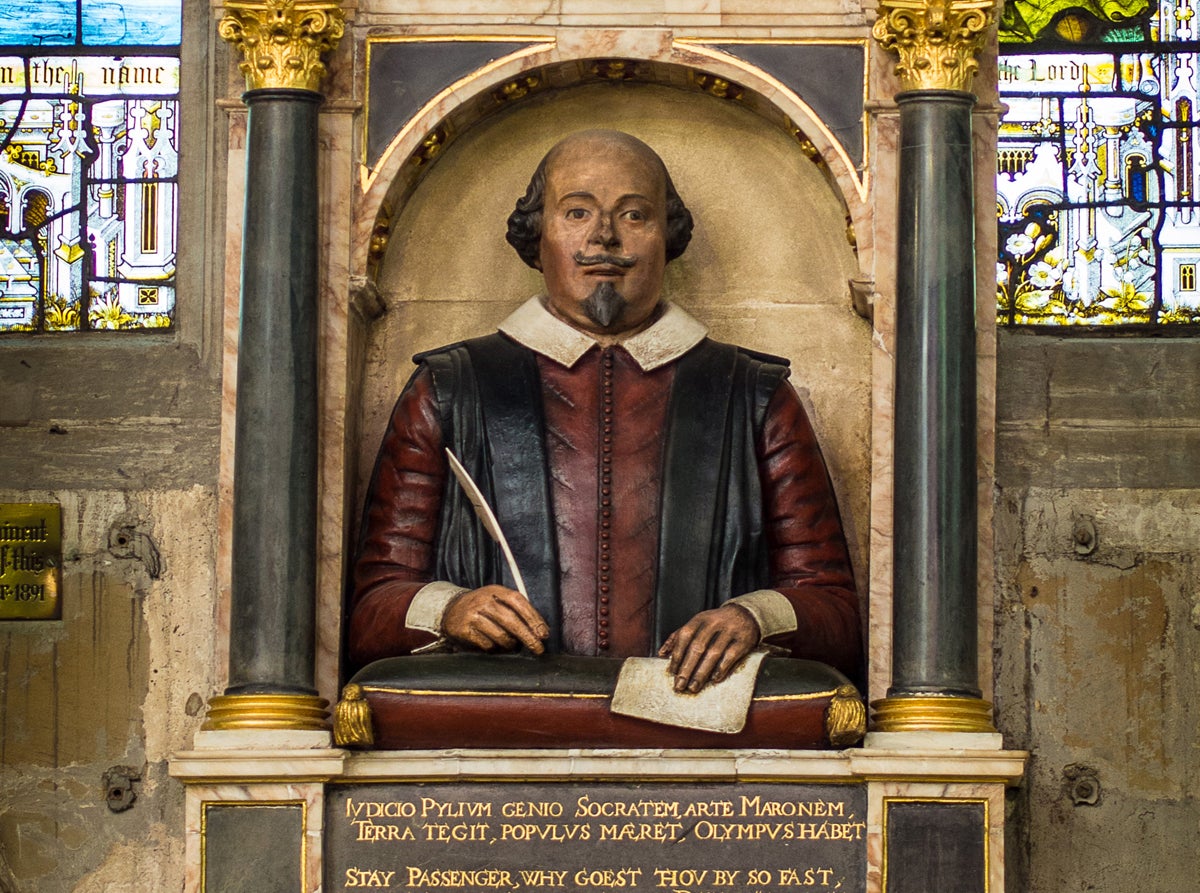

Other paintings exist, showing a similar likeness, and scholarly debates still rage over which is the more credible likeness. Yet, disconcertingly, the bust of the Bard in Stratford upon Avon’s own Holy Trinity Church depicts a rather different figure from the conventional likeness in paintings and the famed engraving. And again, it wasn’t made during Shakespeare’s lifetime, but commissioned four years after his death, so that it could be placed above his grave.

This portly figure hasn’t pleased all Shakespearean scholars. The highly esteemed 20th-century critic, John Dover Wilson, described it as “resembling a self-satisfied pork butcher”.

But time never stands still in new discoveries about how Shakespeare looked. Prof Lena Cowen Orlin, a professor of English at Georgetown University in the US, shoots down the long-held theory that the Holy Trinity bust was commissioned after Shakespeare’s death. She says: “It is highly likely that Shakespeare commissioned the monument. It was done by someone who knew him and had seen him in life. We can think of it as a kind of life portrait, a design for death that gives evidence of a life of learning and literature.”

Orlin’s evidence now attributes the bust to a sculptor “other than we’ve been given to understand”, a craftsman who specialised in creating such memorial monuments from life and whose workshop was “just steps from” the Globe Theatre in London, where many of Shakespeare’s plays were first performed. In other words, the sculptor would very likely have seen, even known, Shakespeare.

The painted effigy is a half-height depiction of Shakespeare holding a quill, with a sheet of paper on a cushion in front of him. In the 17th century, a Jacobean sculptor called Gerard Johnson was identified as the artist behind it. Orlin believes that the limestone monument was in fact created by Nicholas Johnson, a tomb-maker, rather than his brother Gerard, a garden decorator.

Pleasing as it has been to think that a garden decorator had bequeathed the likeness of Shakespeare, the “fact” that it might be a genuine sculptor who knew or at least had sighted the bard, has to be of interest. Dr Paul Edmondson, the head of research at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford-upon-Avon, told The Guardian: “This is truly significant. We can therefore say that is how Shakespeare wanted to be represented in our memories. This is massive. It is compelling new light on what he looked like and how he operated.”

As Apollo, the art magazine, pointed out just a few weeks ago, Shakespeare was very self-aware of “the challenges of self-memorialisation”. In the Sonnets, he broods over the transience of “gilded monuments” that can all too quickly become “unswept stone besmeared with sluttish time”.

The celebrated discovery of Richard III’s skeleton under a Leicester car park in 2012 enabled forensic examination which showed that Shakespeare’s evil child murderer had a soft and gentle face

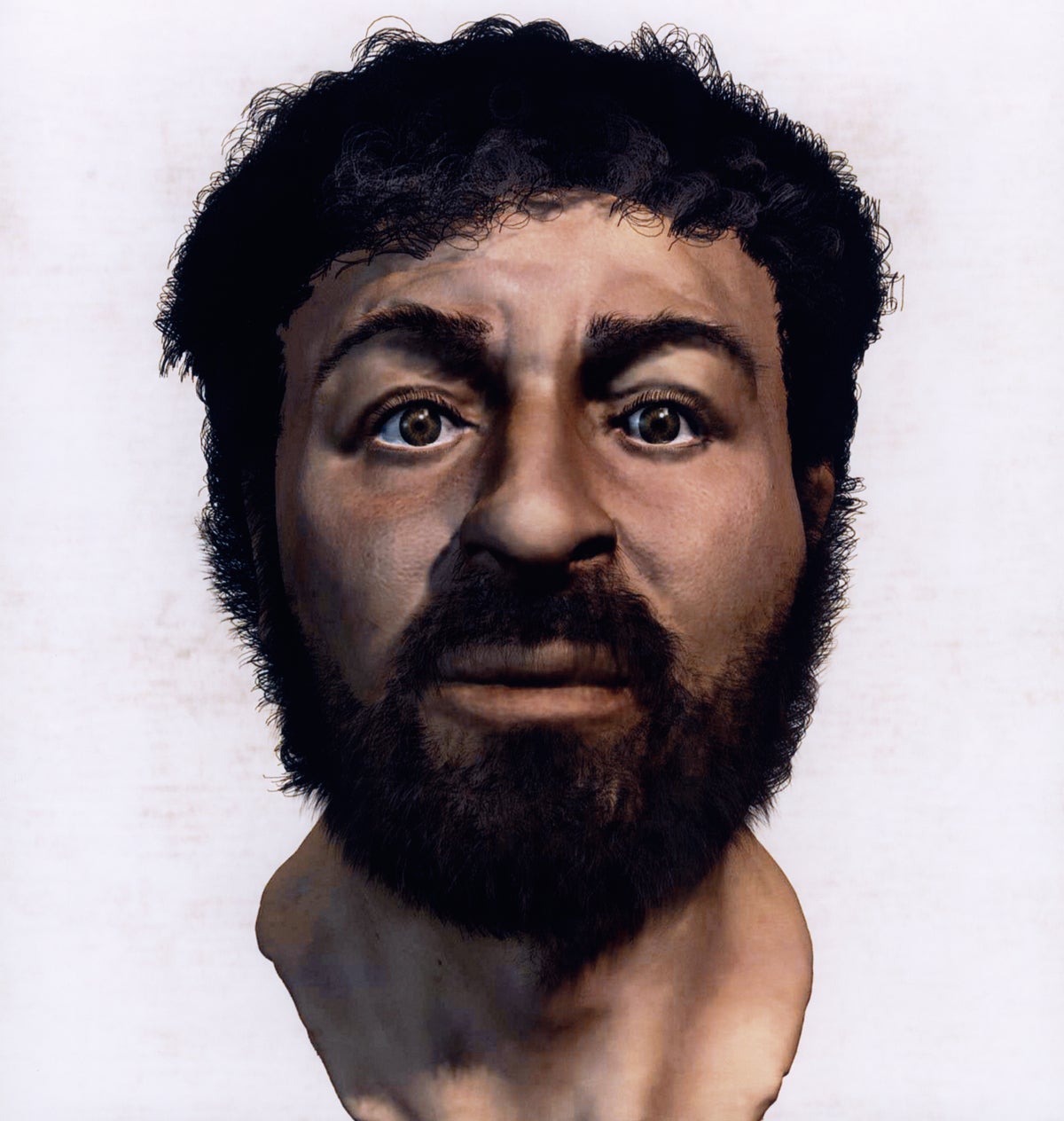

Is Shakespeare the biggest figure whose true appearance continues to elude us? Definitely not. Top of the list must be Jesus Christ, the prime example of someone whose image is fixed in our consciousness, but is unquestionably wildly wrong. We feel we know because he is quite simply the most painted figure in western art. And the vast majority of those paintings portray a saintly-looking man with long hair, a beard, a long white robe with long , white sleeves and, most incredibly of all, blue eyes.

As Professor Joan Taylor, a historian of Jesus and the bible, at Kings College, London, explained: “This familiar image of Jesus comes from the Byzantine era, from the 4th century onwards, and Byzantine representations of Jesus were symbolic – they were all about meaning, not historical accuracy… Byzantine artists, looking to show Christ's heavenly rule as cosmic king, invented him as a younger version of Zeus. What has happened over time is that this visualisation of heavenly Christ – today sometimes remade along hippie lines – has become our standard model of the early Jesus.”

In fact, as a Jewish man of the time, Jesus would not have had long, flowing hair, though he might possibly have had a short beard. The clothing, according to Professor Taylor, is certainly not as portrayed in all the paintings. “At the time of Jesus, wealthy men donned long robes for special occasions, to show off their high status in public. In one of Jesus's teachings, he says: ‘Beware of the scribes, who desire to walk in long robes and to have salutations in the marketplaces, and have the most important seats in the synagogues and the places of honour at banquets.’

“The sayings of Jesus are generally considered the more accurate parts of the Gospels, so from this we can assume that Jesus did not wear such robes.” He would, she says, have been short-haired and wearing a short tunic, with short sleeves.

In 2001, the retired medical artist Richard Neave led a team of Israeli and British forensic anthropologists and computer programmers to create a new image of Jesus based on an Israeli skull dating to the first century AD. Though no one claims it’s an exact reconstruction of what Jesus looked like, scholars consider this image – around five feet tall, with darker skin, dark eyes, and shorter, curlier hair – to be more accurate than many artistic depictions.

Indeed, scientific research has blown a hole through long held imaginings of what famous historical figures looked like. Analysis of genetics and digital scans showed that the ancient Pharaoh King Tut was a frail boy with a club foot and heavy overbite. And, of course, the celebrated discovery of Richard the Third’s skeleton under a Leicester car park in 2012 enabled forensic examination which showed that Shakespeare’s evil child murderer had a soft and gentle face. He did though have a deformity of the spine, so parts of the legend were true.

Who better to end with than Santa Claus? Surely, we all know what he looked like. Once again, no. The remains of St Nicholas, the original Santa Claus, have been in a church in Bari, Italy, since they were stolen from Turkey in 1087. Measurements of his skull have revealed that St Nicholas had a small body – he was only 5’6” – and a huge, masculine head, with a square jaw and strong muscles in the neck. He also had a broken nose, like someone had beaten him up.

Perhaps, we have a psychological need to know what the great figures from history looked like. But science increasingly confounds long-held and long-cherished images. The scholar Ben Johnson had the best advice in his foreword to Shakespeare’s First Folio: “Reader, looke / Not on his Picture, but his Booke.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments