Who was James Webb, the controversial man whose name adorns a telescope?

Mick O’Hare explores the bureaucrat responsible for so much of Nasa’s space exploration, and also the controversies and claims of homophobia that surround him

We’re burning up,” screamed the crew of Apollo 1 in a garbled transmission as fire engulfed the capsule on its launchpad. The transcript makes grim reading. It took five minutes to reach what was left of the three astronauts, who asphyxiated and then burnt in the oxygen-rich atmosphere of their spacecraft. It had only been a launch rehearsal, but it had gone disastrously wrong. That it took place on Earth, rather than in space, somehow made it more terrible.

It was 27 January 1967, and they were the first American astronauts to die in service. Roger Chaffee and Virgil “Gus” Grissom were interred at Arlington National Cemetery on 31 January, Ed White at West Point Military Academy Cemetery on the same day.

James Webb was at the funerals in Arlington. The director of the Apollo missions knew these deaths could likely spell the end of America’s mission to land a man on the moon by the end of the decade. But he was prepared to sacrifice his career to ensure that aspiration remained extant.

The orbiting James Webb Telescope – the successor to Hubble – has already sent back some incredible high-res images as it prepares to reach full alignment in June or July where it will beam back images from far deeper into space. But how many people know the story of the man after whom it is named (but nearly wasn’t)?

Without Webb, Apollo 11 and its commander, Neil Armstrong might never have taken that “one small step” onto the surface of the Moon in July 1969, however, he’s a controversial figure: a hero to some, anathema to others.

And, as a bureaucrat rather than a physicist, engineer or astronaut, why was he chosen to be so memorialised?

Webb was Nasa’s second chief administrator. He had been reluctant to take the job, having no background in aeronautics or spaceflight, but US president John F Kennedy had spotted that he was politically savvy and had a history of success working as a political advisor in Washington DC and in private enterprise. In the end Webb was persuaded.

“He had experience in politics in DC, and knew how to work Washington,” says Teasel Muir-Harmony, curator of the Apollo spacecraft collection and historian of spaceflight at the Smithsonian in Washington DC. “He had been deputy secretary of state and had radically improved his department’s organisation. And before that he was director of the Bureau of the Budget in the Office of the President, meaning he was aware of how to secure the necessary funds for the expensive job of putting people into space. Kennedy realised Webb was exactly what Nasa needed. The president’s own science advisor Jerome Wiesner had warned against crewed spaceflight as a waste of money and too big a risk. But Kennedy assured Webb he wouldn’t be following Wiesner’s advice. Webb realised he would have autonomy. And so took the role.”

Webb replaced Hugh Dryden in February 1961, only shortly before Kennedy committed to put an American on the Moon by the end of the decade. Webb was there to make that happen. Both men knew the United States was behind its rival the Soviet Union in what would become known as the “Space Race”. The Soviets had already launched the world’s first artificial satellite and would soon put the first man and the first woman into space. Webb had much to do.

Nasa had been established to bring a focus to America’s goals in space. The command economy of the Soviet Union had ensured that all the early achievements in Earth orbit were theirs alone. Under the direction of Webb, Nasa shifted from being a loose association of research institutes to a more centralised organisation, similar to that which had brought success to their ideological rival. He oversaw the single-astronaut Mercury spaceflight programme before creating the Manned Spaceflight Center in Houston, Texas from where the two-man Gemini programme was coordinated. Mercury and Gemini paved the way for Apollo, the missions that would take the US to the moon.

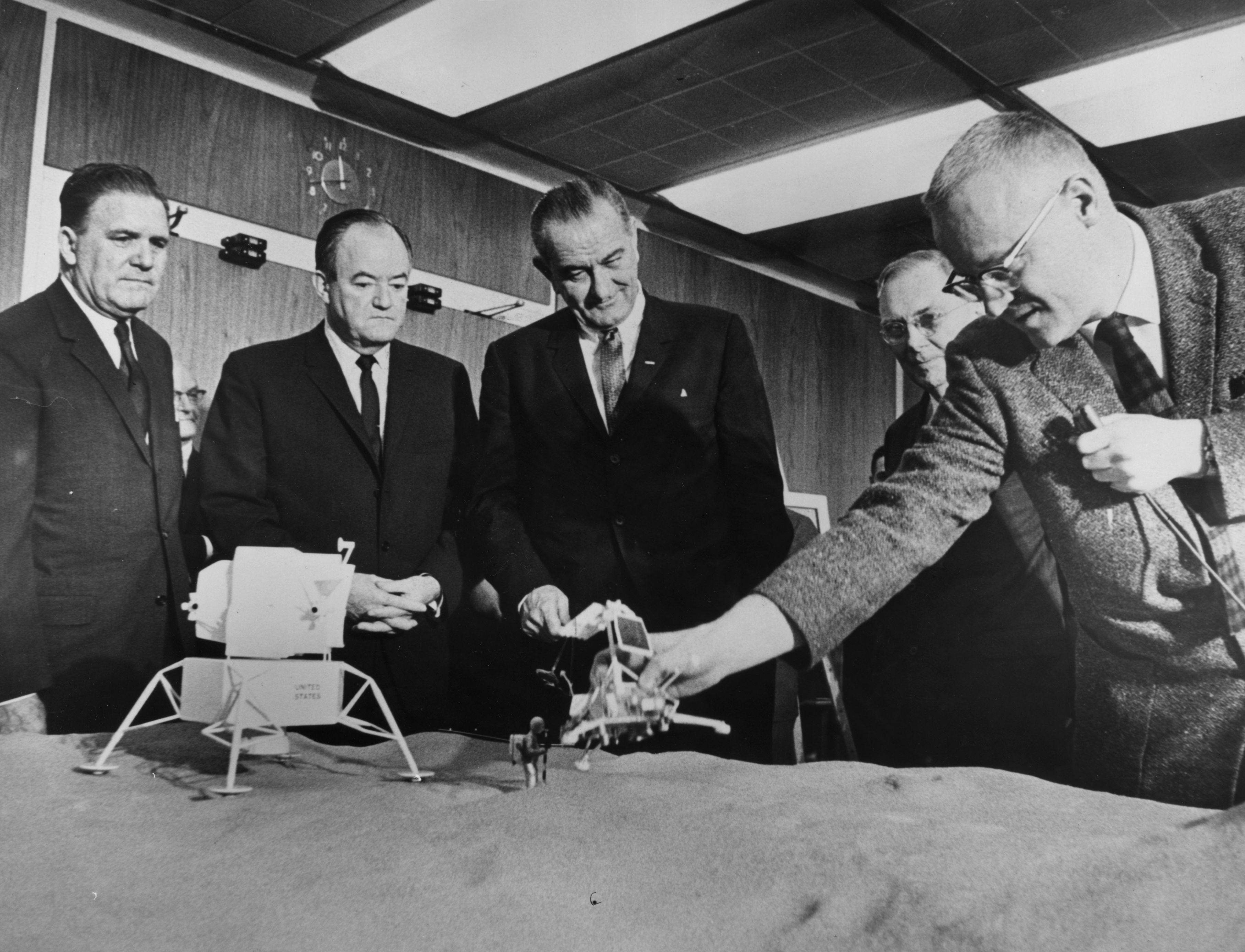

It was one of the most impressive examples of project management ever undertaken. For his seven long years of tenure, Webb masterfully played the role of diplomat, politician, public servant and patriotic standard-bearer as he cajoled, wheedled and sweet-talked Congress into bankrolling and supporting Nasa. His prior experience on Capitol Hill paid dividends while his Democratic Party membership kept him close to Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon B Johnson. His network of contacts in Washington DC brought continued financial support for Apollo as he backed himself and his team to meet Kennedy’s goal. Under him the US was inching closer to a Moon landing. The Soviet Union’s programme was faltering, but then came Apollo 1.

Webb knew his neck would be on the line. “Apollo 1 changed the trajectory of his career,” says Muir-Harmony. “It threw a spotlight on his responsibilities as an administrator. Before it happened, he had focused on the politics of his role in DC rather than the actual technical programme. Apollo 1 was an admission that the programme had fatal flaws.”

The American public was traumatised by the tragedy, Congress wanted answers. Webb knew he had to bear responsibility but equally he knew that Apollo was close to achieving its goals. The programme could not be allowed to founder.

He argued that only Nasa could handle the accident investigation – if left to outsiders, emotion might overshadow the outcome. “We’ve always known sooner or later that something like this was going to happen…” he admitted with uncomfortable honesty. He insisted to Johnson that Nasa would be truthful and that any blame accorded to him or his team would be duly apportioned. This “infuriated Apollo’s enemies,” records Piers Bizony’s book about Webb, The Man Who Ran The Moon. But despite opposition from within and without his own Democratic Party, Johnson agreed subject to Congressional oversight. But “the two men shook hands on it,” writes Bizony, “with the condition that Johnson could change tack if he had to.”

Because Webb knew the technical issues could be addressed, he was aware that if he held himself culpable that would be a sacrifice palatable to the politicians

And while committees in both houses of Congress probed Nasa’s affairs, learning of a 1965 internal report that questioned quality control in companies involved in the manufacture of the administration’s spacecraft, especially the contractor North American Aviation, came to light. Webb convinced them rightly or wrongly that the failings had little bearing on the tragedy. Simultaneously, though, he was demanding resignations at North American.

Meanwhile, some of the blame was falling on Nasa engineer and manager Joe Shea. “In part he was held responsible for certain things like the capsule’s oxygen-rich atmosphere which allowed the fire to burn quickly and his use of flammable Velcro,” explains Muir-Harmony. “The astronauts, too, were aware of these problems and had raised them with Shea even before the fire.”

Shea would later suffer a breakdown and be moved to a different role in the administration. It has been speculated that this was to avoid him giving testimony to Congress where Webb was attempting to carry the can for the tragedy.

In front of his inquisitors, Webb was in equal measures veracious and wily. Future vice-president Walter Mondale, then sitting on the Aeronautical and Space Sciences Committee, wrote that Nasa’s submissions to the committee were marked by “evasiveness” and a “lack of candour”, and showed a “refusal to respond fully and forthrightly”.

Nonetheless, Webb attended every meeting to which he was summoned, taking a personal grilling at each, and successfully deflecting the public and political backlash from Apollo 1. By shouldering much of the blame he demonstrated that while errors had been made at administrative level, Nasa was structurally sound and the Apollo programme itself was sturdy. Apollo would be grounded for review and redesign and chief flight director Gene Kranz, the man who would oversee the Apollo 11 landing and the Apollo 13 rescue, insisted that from now on, “nothing less than perfection” would do. By November, only 10 months after the fire, the uncrewed Apollo 4 mission flew into orbit.

Webb was fortunate that he and Apollo always had pretty much the unconditional support of President Johnson. “Johnson was a big supporter and had backed Kennedy’s aims,” says Muir-Harmony. Although Webb had agreed with Johnson that he could cease backing him if it became politically expedient, Johnson’s support never wavered.

“There was always a general political consensus that Apollo should continue,” says Muir-Harmony. “To stop would have been to backtrack on the aspirations of an assassinated president. Kennedy, ironically, had worried about the costs – Webb had talked him into committing 5 per cent of the US federal budget to Apollo – but Johnson was always supportive. Cancelling it would have been an affront, perhaps, to Kennedy’s legacy and also a big backward step having come so far.”

Without Johnson’s support, Webb’s appearances in Congress would have been even more arduous. But still his stock had fallen very low. When Johnson announced he would not be running for re-election, Webb realised his position was untenable. “Nasa’s reputation was tarnished and somebody had to be a scapegoat,” explains Muir-Harmony. “Because Webb knew the technical issues could be addressed, he was aware that if he held himself culpable that would be a sacrifice palatable to the politicians and also the public who, after the tragedy, wavered in their already meagre support of Apollo. He also knew that the incoming president [Richard Nixon would be elected in November 1968] would likely want to appoint his own Nasa administrator.”

Webb resigned in October 1968, just before Apollo 8, the first flight to circumnavigate the Moon, was launched to worldwide acclaim. One of his last acts in the programme into which he had invested his career had been to advance the timing of Apollo 8 after he was briefed by the CIA that the Soviet Union was about to commence lunar operations. Until that point the two nations had been pretty much neck and neck. Despite his departure, it is widely accepted that without James Webb, Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon eight months later would not have been achieved.

Yet his legacy ran a little deeper. All the time Webb was aware of the political aims of Apollo he also demanded that science play a key role in Nasa’s activities which he hoped would benefit both education in the US and the nation’s academic institutions, something he believed the Soviet programme lacked. Before his appointment he told both Kennedy and Johnson: “I'm not going to run just a one-shot programme. If you want me to be administrator, it’s going to be a balanced programme that does the job for the country.”

Under Webb, robotic spacecraft explored the lunar environment, while uncrewed probes flew to Mars and Venus, and satellites discovered more about the Earth and its atmosphere. “He insisted that planetary exploration was a priority too,” says Muir-Harmony “He looked beyond Apollo and crewed spaceflight.”

He also had a social conscience, asking the question why “if the US could accomplish Apollo, it couldn’t do something for grandma with Medicare?” He set up programmes to replicate Nasa’s management practices in the application of social policy, transforming public health and welfare administrations across the US. “He had a sense of public service and wanted to apply Nasa’s skillset to solving society’s ills society. He saw his role as an opportunity to help his nation,” says Muir-Harmony.

It was as much down to his advancement of science and healthcare as for his achievements on crewed spaceflight that Nasa decided in 2002 to name its next generation space telescope in his honour. But trouble was afoot.

Archival evidence suggests Webb was aware of the policy and although the sackings might not have been directly attributable to him, his silence implies complicity in the persecutions

In March 2021, Scientific American published an editorial stating that prior to arriving at Nasa, Webb was complicit in purging homosexuals from positions in public life during his time working at the State Department in Washington DC. This followed on from an earlier article in 2015 by sex and relationship advice columnist Dan Savage, that asked “Should Nasa name a telescope after a dead guy who persecuted gay people in the 1950s?”

The Scientific American article also drew attention to the dismissal of Nasa employee Clifford Norton in 1963 after Webb had joined the space administration. Norton had been arrested for “homosexual activity” leading to him being fired for “immoral, indecent and disgraceful” behaviour. At that time homosexuality was outlawed in government departments by federal decree, ostensibly to prevent attempts to blackmail government employees, but equally representative of the hostility displayed towards gay people in that era.

Archival evidence suggests Webb was aware of the policy and although the sackings might not have been directly attributable to him, his silence implies complicity in the persecutions. “As someone in management,” wrote Scientific American, “Webb bore responsibility for policies enacted under his leadership,” a maxim Webb himself seemed to acknowledge by taking responsibility for Apollo 1. A group of 1,200 astronomers agreed with Scientific American, writing a letter to Nasa demanding the telescope be renamed.

Nasa defended its decision, citing a lack of actual evidence that the administrator had been directly involved in any persecution. “At best, Webb’s record is complicated,” says cosmologist Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, who co-authored the article. “At worst, we’re basically just sending this incredible instrument into the sky with the name of a homophobe on it, in my opinion. Either he was a wildly incompetent administrator and didn't know that his head of security was interrogating employees in Nasa facilities, or he knew exactly what was going on.”

Nasa’s senior science communications officer Karen Fox insisted the administration had looked into the accusations and “having exhausted our research efforts… have not uncovered evidence warranting a name change.” Prescod-Weinstein responded by saying Nasa had a lack of transparency in its response to her allegations.

The former Nasa administrator who approved the decision to name the telescope after Webb was Sean O’Keefe. “This is an important matter of history, to understand how we could possibly have tolerated the purging of talented professionals on the basis of their personal preferences,” he said. “It’s objectionable. No question about it, and I applaud the effort to surface the visibility and awareness of it.” However, he went on to add that he hadn’t seen anything to convince him that Webb was directly involved in ousting gay colleagues. “To suggest he’d be held accountable for that activity when there’s no evidence to even hint at that is an injustice.”

So the name remains but the dispute rumbles on. James Webb died in Washington DC on 27 March 1992, his legacy tarred on two fronts, possibly both of his own making. And while he has, to a certain extent, been rehabilitated, lauded even, following his selfless devotion to the Nasa cause, following the Apollo fire, the repercussions of the US government’s stance – and by extension Webb’s – towards homosexuality is less clear cut. Doubtless he was a man of his era, which is, of course, no excuse for discriminatory behaviour. The mores of the age suggest he would likely have been, at best, ambivalent to homosexuality. Even ignorance of the federal ban on homosexuals working in government is no defence. As Prescod-Weinstein says that would indicate “wild incompetence”.

“Lots of questions remain,” admits Muir-Harmony. “There is no documentary evidence of Webb supporting discrimination or expressing his views on it, but investigations continue. He did advocate for African Americans both in Nasa and outside and contributed to the civil rights movement but obviously that doesn’t absolve him of sexual orientation discrimination. But he was in favour of what we’d now call inclusivity.”

From self-made pariah, to exonerated administrator and right back to pariah figure once again, Webb’s legacy is divisive, complicated and intriguing. “If the average American knows of a Nasa administrator it will most certainly be Webb,” says Muir-Harmony. “But I guess he was tarnished twice – by Apollo 1 and now by the LGBT+ rights issues. So his legacy is difficult to ascertain yet his overriding influence when it was needed most remains a major factor. He was, to quote Harry Lambright, his biographer, ‘An administrator and a politician’ which at that time was exactly what Nasa needed.”

Without doubt, the arguments will rage on whether or not the telescope is renamed. However, the telescope itself is, quite obviously, a completely innocent party. As we await its first fully aligned, high-resolution images we should, perhaps, not let the controversy overshadow the cosmological wonders it is set to reveal.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments