To ask why Raphael matters today is to ask why art matters

At the age of 16, he would be described as a ‘master’ in his own right... by the age of 37 he would be dead. The renowned Italian painter died 500 years ago today. Kevin Childs reflects upon the man, his art and his enduring legacy

Raphael Santi of Urbino, who died on 6 April 1520, was one of the most influential artists of all time. Yet his life and work represented an impossible ideal: tensions between past and present, war and peace, status and identity, and love and life, which played out in the brilliant colours he used to portray moments of psychological intensity. Through the prism of those colours most associated with Raphael – black, red, gold and blue – this article reflects upon the man, his art and his legacy.

Black

Good Friday, 6 April 1520.

The sun had set. A pale streak of tin oxide over Rome’s Janiculum Hill in an otherwise cloudy sky of pitch. People made their way to stand vigil outside Old St Peter’s. The Pope, as usual, had ordered all lights to be extinguished in churches and public places, so that a darkness over the streets and squares of Rome would help the faithful remember the moment Christ’s body descended from the cross and his spirit descended below. Through the night, the harrowing of hell had begun.

But all day across the threshold of Palazzo Corsini, people had come and gone in the hope of news – good news, bad news, any news. And all day the reports had not changed. The visitors trod through the vestibule hung with tapestries, up the broad stone staircase to the door of a large room. There they crowded, catching a glimpse inside where a bed had been placed. On the bed, pale as ashes, a man in his mid-thirties would from time to time raise his head to drink a little water, barely wetting his cracked lips, his brown eyes only half open.

Raphael Santi of Urbino, the Prince of Painters, hailed by Rome as the greatest living artist, drifted in and out of consciousness. And as night fell and torches flickered at the doorway – yellow to orpiment orange and then bright arsenic red, light umber and a flash of cinnabar in the heart of the flame – Raphael’s body, burning and feeble from days of fever, his lungs slowly drowning, and his doctors with no clue how to save him, gave up the struggle.

The 37-year-old made his confession. Earlier that day, a young woman had left the house. Margarita Luti had been the artist’s lover for some years, the woman about whom many stories would be told and of whom Raphael had made tender portraits. But now he was dying, and the priests insisted it wrong for him to do so in a state of sin. Margarita was sent away from his bedside. Someone else would say it was her fault, that Raphael had been up too late and too long making love to her, and on his way home had caught a chill. Nonsense, certainly, but Margarita somehow would take the blame.

In the hall that had doubled as a studio, a large painting stood more than four metres high, a few brush strokes away from finished, but miraculous for all that. It had been commissioned by the Pope’s cousin, Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici, for his episcopal church in France. Raphael had laboured over it alone, experimenting with tone and colour, changing the narrative radically. It would become one of the most celebrated and copied works of the Renaissance.

In The Transfiguration, a young, beautiful Christ, dressed in brilliant white robes amid clouds of intense violet white, soars above a small hill, the Old Testament prophets Moses and Elijah either side of him and three astonished apostles prostrate below. But this is not the human interest of the picture. Beneath, in the space nearest to us, the rest of the apostles are confronted by the family of a boy, depicted off-centre on the right, who is in the grip of feverish convulsions, body and face contorted, eyes rolling. It’s almost certainly a depiction of an epileptic fit. This is our world, confused, conflicted, dark, in contrast to the shimmering light of the scene above. The apostles gesticulate wildly, unable to help, powerless to summon up a miracle in this earthly realm. One points towards the hill as if to say, “He’ll return again, he will help.”

At what would be our eye level, a woman dressed in pale pink and deep blue, her firm body defined by her clothes rather than concealed, in a novel attitude, turns to face the apostles while indicating to the tortured boy, pleading with them. It seems no one pays her much heed. But we notice her unusual power and grace, as almost everyone has since the painting was first shown. She is a goddess, the perfect expression of contrapposto, the shifting of the body to create a strong, sinuous sense of movement. It’s also typical of Raphael to have focussed our attention on a woman at the epicentre of his drama.

Vibrant colours – green earth, burnt umber, vermillion and yellow ochre – emerge from and sink into deep shadows, burning in stark contrasts, articulating limbs, gestures, expressions against a low raking light. It’s the most astonishing use of chiaroscuro – the dramatic contrast between highlights and shadows to create a sense of volume – before Caravaggio adopted it at the end of the 16th century.

Raphael’s biographer, Giorgio Vasari, who considered this piece to be his greatest, nevertheless criticised the artist for using a black pigment derived from the soot of oil lamps which, he believed, over time had darkened the painting. But Raphael needed the darkest black to create the strongest contrasts, the most dazzling relief, the stark crisis of mortality in which human uncertainty grasps at a vision of faith that is almost too perfect to be of any real comfort.

To ask why Raphael matters today is to ask why art matters – and more specifically, the sort of art that combines technical mastery, psychological insight and a cracking good story. Raphael painted for a generation that was on the cusp of our modern world. Inspired by stories he had heard about the dazzling realism and sheer beauty of ancient painting, he wanted to recreate a style that had vanished 1,500 years earlier, the works of its most famous artists – Apelles, Zeuxis, Protogenes – having entirely disappeared.

He is the most objectively beautiful of painters, almost self-consciously so because he was reinventing, or reconstituting, the concept of beauty from what remained of antiquity: some crumbling ruins, a handful of sculptures and a few more words – an imagined ideal.

To ask why Raphael matters today is to ask why art matters – and more specifically, the sort of art that combines technical mastery, psychological insight and a cracking good story

In a little less than 20 years, the years in which Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael and Titian came to maturity, the ancient world and the modern would collide to create a hybrid culture of unmatched beauty, and Raphael was at its forefront. Ancient writers told how their world could be brutal, like his own, but also beautiful, an age of harmony and happy mediums dreamt up by its philosophers and poets, the same philosophers and poets Raphael was to depict on the walls of the Vatican in the rooms that are named after him.

He wanted to conjure this world through painting and architecture, yes, but also through a spirit of being. He was the painterly equivalent of those gentle inspired minds, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Pietro Bembo, Baldassare Castiglione, who recognised human dignity, amid all the pain and horror, as the essence of that being.

Raphael came to Rome towards the end of the first decade of the 16th century, at the request of Pope Julius II, to paint a scene in a new private library in the Vatican. He was known for delicate, charming Madonnas and coolly elegant saints, immaculately conceived and perfectly painted in icy pinks, blues and greens. His landscapes rivalled those of the northern European artists Van der Weyden and Memling. He’d already been drawn to the mysterious techniques of Leonardo da Vinci and the boldly radical style of Michelangelo from a few intermittent years in Florence. He was not yet the Prince of Painters, though, but he had the manners and looks of a prince, and the Pope wanted him near.

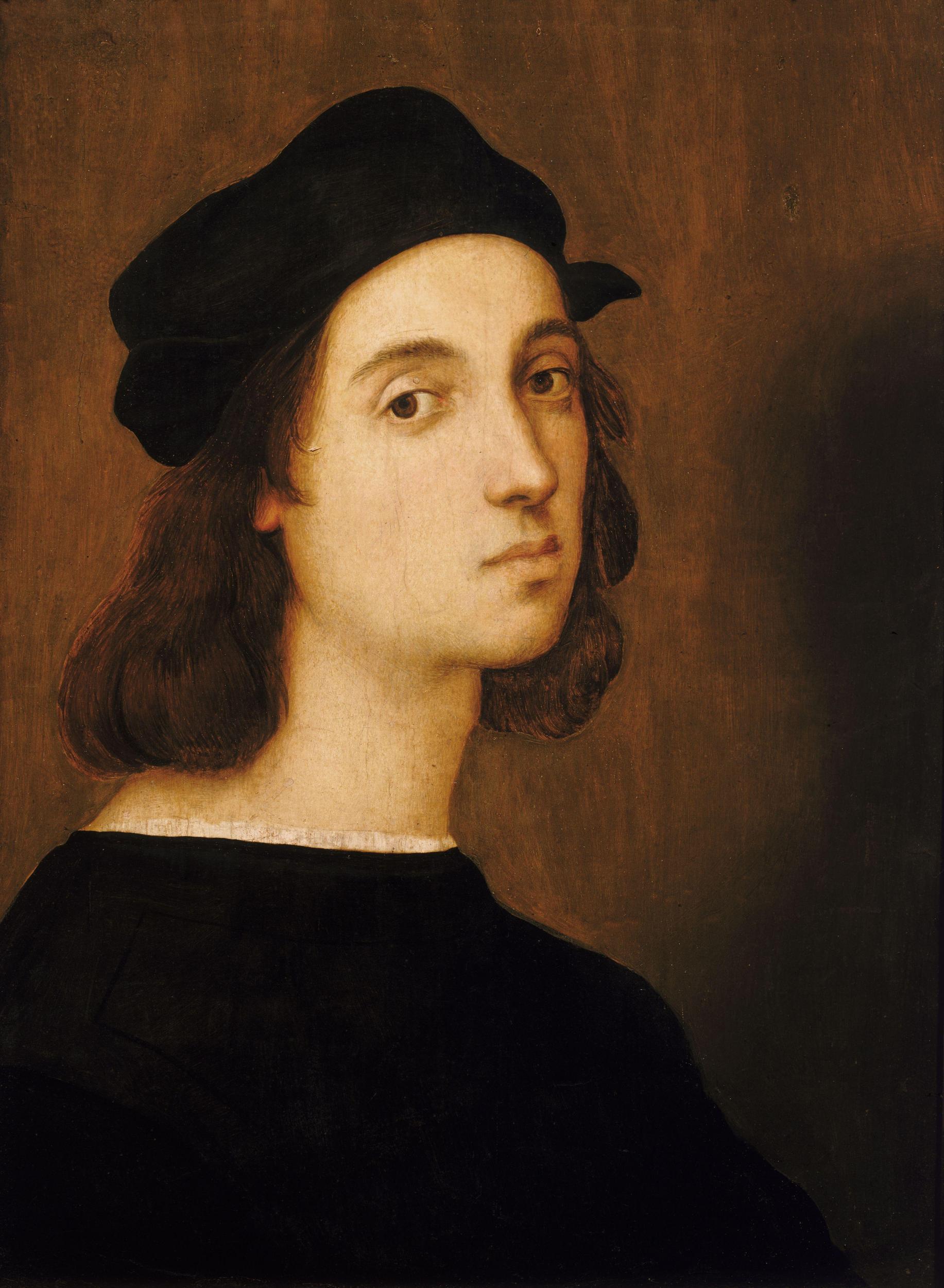

A self-portrait from a little before this time shows a beautiful youth glancing sideways at us, his fine head with its mass of auburn hair perched on a long neck, the perfectly arched brows and hooded eyelids giving him a nonchalant look. And he wears black, lampblack as it was called, with just the hint of a white shirt collar at the base of his throat.

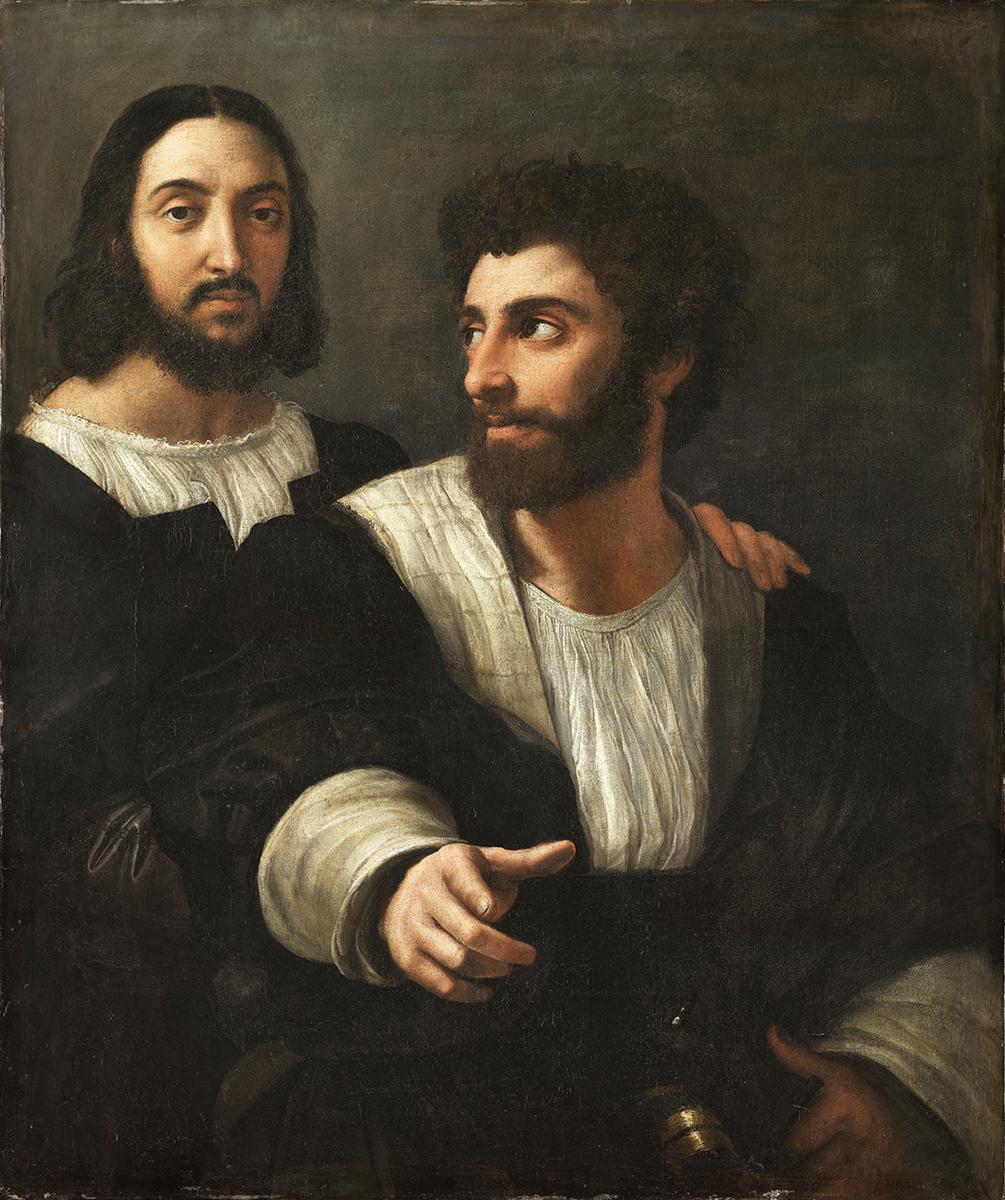

He wears black again some years later in a strange, sombre self-portrait with a friend. He’s older, bearded, pale, those same arched brows framing eyes that are tired. He’s probably only a year or so from the fever that would kill him, and the hand he rests on the shoulder of his companion might already have a dampness about it. Only when we get close to the painting do we realise he isn’t smiling. By contrast, the other man is vibrant and energetic, pointing at us, moving forward into our space but turning to look at Raphael as if to urge him to follow. Raphael seems reluctant.

Raphael’s friend, Baldassare Castiglione, had always recommended black. “I prefer [clothes] always to tend a little more towards the grave and sombre rather than the foppish,” he would write. “Hence, I think black is more pleasing in clothing than any other colour.”

Black was the costliest of fabrics. No black pigment would hold in cloth without running, so the dyers needed to colour blue and red, blue and red, blue and red many times until a deep, dark lustrous tint was achieved. The process made the cloth prohibitively expensive. Both Raphael and his companion announce their status by wearing it. But it also gives the double portrait a sombre look. For Raphael, black seems to denote mortality, which is the essence of the human condition. It is as though these men are mourners at some grand Roman wake.

Red

Down a cobbled street, soldiers are moving at a trot, pikes and crossbows shouldered, helmets gleaming darkly in the sun. They wear leather doublets and red hose, bright vermillion. Across the fields of yellow stubble, they will march against a milky blue sky. The young duke at their head rides to defend Holy Mother Church against her enemies. His red cloak, the colour of madder roots, of dried blood, billows out behind him. As he watches them pass, the young boy at the roadside will remember the colours and movement.

Raphael was born on Good Friday 1483, falling then on 28 March, in the small city of Urbino in the Marche, a fertile, hilly region in eastern Italy that gently declines towards the Adriatic Sea. His father, Giovanni Santi, was a local painter and poet who worked for the most important patrons around, Urbino’s dukes Federico da Montefeltro and his son Guidobaldo. He painted altarpieces and Madonnas and wrote plays and poetry for ducal festivities.

As a small child, Raphael lived in the shadow of the Montefeltro palace. Urbino, the Little City, was just that, “a city in the form of a palace” as Castiglione would call it, perched on a hill, the elegant arches of its courtyards dancing in the southern light, its wide stone staircases and tall gilded ceilings the latest word in taste.

Montefeltro was a mercenary captain, or condottiere, but his skills in war kept war from Urbino for much of his rule. Guidobaldo, though only a child when he inherited his father’s duchy a year before Raphael’s birth, would hope to do the same, but the times were not kind to him, and more than once he would lose his little duchy. But while it lasted, he and his wife, Elisabetta Gonzaga, attracted some of Italy’s most wonderful minds to Urbino, so that Raphael grew up among poets and philosophers, many of whom would become his friends, like the irrepressible Castiglione, who later described the brilliant conversations in the palace of Urbino in his Book of the Courtier.

In August 1494, Raphael’s father died after a long sickness, leaving the 11-year-old an orphan. Raphael’s mother and little sister had died a few years earlier. It was a dangerous time to be left alone. Two months after Giovanni died, the French king Charles VIII invaded Italy to claim the throne of Naples, launching what would become decades of brutal war on the peninsula, sacking cities and slaughtering their inhabitants, carting off precious objects, tapestries, gold- and silver-work, paintings and precious antiquities.

Duke Guidobaldo fought first for the French as they made their triumphal way through Italy, but later switched sides to join the League of Venice against France, eventually losing his palace to Pope Alexander VI’s ruthless and greedy son Cesare Borgia.

The eyes of the boy Raphael absorbed all this. He was living under the guardianship of his uncle, a local priest, while employed alongside his father’s old assistants in the painting workshop. They had taken him under their wing, but within five years, at the age of 16, he would be described as a “master” in his own right and was already working on commissions from patrons beyond Urbino. He produced small lovely things then.

The tender dreams of a knight resting on his scarlet shield; the three Graces dancing in coral necklaces and holding rosy red apples; gentle Madonnas in dark red tunics, the colour of royalty, the colour of martyrdom. In a painted world of harmony and peace, red was the only concession to the violence that surrounded him.

Vasari tells us that Raphael had been apprenticed by his father to the Umbrian painter Pietro Perugino. It’s unlikely any such formal relationship existed, but at one time the young lad’s style was certainly very close to Perugino’s. They painted similar subjects – at times Raphael’s work appeared to be an improvement on Perugino’s compositions, as in the versions of the Betrothal of the Virgin they both painted for patrons in the same region.

So similar in terms of structure and style, Perugino’s staid, statuesque figures, stock Roman architecture and standard perspective are transformed by Raphael through a more dynamic rendering of style and movement – even the architectural backdrop is more daring. His daring splashes of madder lake and cinnabar red shake up the borrowed composition.

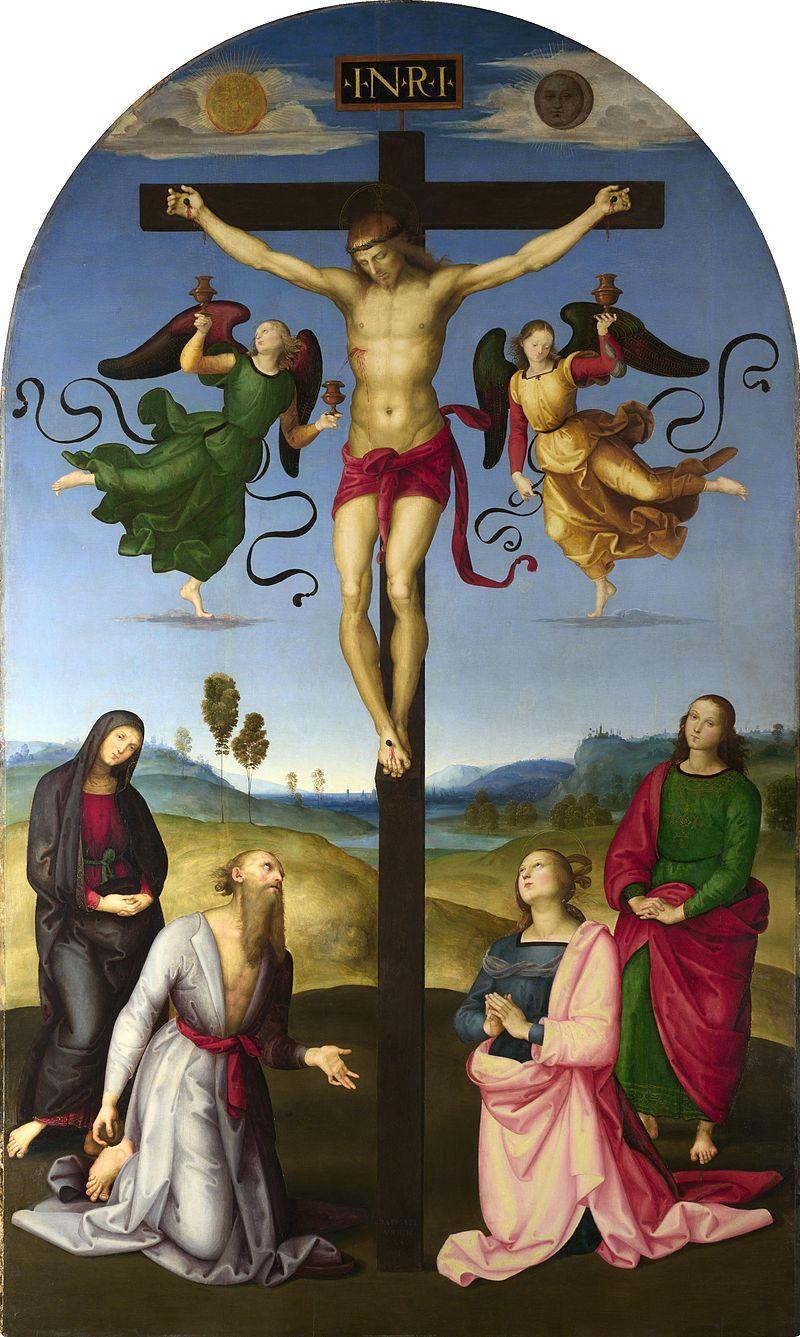

Even in his version of the crucifixion, the teenage Raphael surpassed the older artist’s timid use of colour: red in Christ’s loincloth, normally snowy white, in the robes of the Virgin and St John as well as Jerome’s sash. It’s as though the boy were trolling Perugino in pictures.

Raphael was never anyone’s apprentice – despite what Vasari would have us believe – but an assimilator, a thief even. He didn’t learn from Perugino; he stole from him and did it better.

From around 1504 Raphael started going to Florence because he had heard of the miracles of art being done by Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, who were competing to produce battle murals in the main meeting hall of the Florentine government. He saw their vast cartoons – full-size drawings of the final compositions – and understood the revelation they offered: how Leonardo’s figures emerged fully rounded from a sort of primordial mist in rage and passion; how Michelangelo exalted the male nude and counterfeited three dimensions through mastering the technique of foreshortening that the ancient painters had known, so that his figures seemed to leap from the cartoon like the carvings on an ancient sarcophagus.

And though Raphael recognised he could never do what they had done, he could assimilate the lessons and create a style all his own. “So,” writes Vasari, “he decided not to waste his time by imitating Michelangelo’s style but to attain a broader excellence in the other fields of painting … His example might well have been followed by many contemporary artists who … if they had followed Raphael … would have benefited themselves and everyone else.”

Gold

He looks at the wall before him. A difficult space to tackle, with a large window opening in the centre, its shutters now closed, dividing the space. The wall is how he imagined it. In the candlelight he looks through a black iron grill above the window opening, which dominates the centre of the scene, all painted in lampblack, the darkest pigment. This screen leads to a prison. St Peter is sleeping, enchained, for the moment oblivious to the miracle.

An angelic figure dressed in robes of rose gold leans forward to wake him, whose bright golden light fills the cell, creating a brilliant pattern of squares against the iron grill. It’s one of the finest of night scenes, and the seeing of it through the grill of the prison cell creates an extraordinary illusion never attempted before. Soldiers, sleeping either side of the cell, reflect the light of the moon and the dazzling apparition, their armour drenched with it. On the right of the fresco, the golden aureole, pale ochre through to orpiment orange and lead white, follows the angel as he leads Peter by the hand to safety.

Raphael, who had devised the scene first through individual figure drawings, only came to the boldness of the design when the wall was prepared with wet plaster. Then his eye was like a camera, imagining everything at once as well as the sequence of events: how St Peter’s miraculous escape from Herod Agrippa’s prison runs through the line of the soldier on the left, his back to us, pointing his companions towards the eerie light at the centre, to the tension as Peter is led past sleeping guards to freedom.

The features of Peter are a posthumous portrait of Pope Julius II, who had recently died. When Raphael opens the shutters of the window, the burst of sunlight through the wall makes the scene seem like a resurrection.

Raphael had left commissions half done in Florence and Perugia when he was summoned to Rome by Julius II in the autumn of 1508. His reputation as a prodigy went before him, but he was still expected to prove himself, and while Rome at the beginning of the 16th century was not yet paved with gold, there was gold to be had from a pope who loved both art and handsome young men.

But the city was full of ghosts then: vast carcasses of once magnificent buildings, temples, baths, theatres sheltering sheep and cattle, the bones of saints, the scars of feudal wars. Raphael would come to champion the preservation of these ruins from speculators. As you walk through the Forum or the Markets of Trajan today, consider the debt owed to him. But Rome was also beginning to fill up with wealthy men who commissioned palaces for their ease and chapels for their souls, all of which required a decorator’s hand. In Rome, Raphael would become the greatest decorator who ever lived.

He was set to work in the Pope’s library at around the same time the scaffolding in the Sistine Chapel was put up and Michelangelo closed off the ceiling to paint in peace. The tension between the two artists has become legendary, although much of it may have been only that. They were rivals – later Michelangelo would claim Raphael learnt all he knew about art from him – and strove after the same ends. But ultimately, Michelangelo would be conflicted by his fascination with the sensual world of pagan antiquity. Raphael would embrace it.

Raphael certainly speculated about what was happening on that ceiling, but Michelangelo must also have heard whispers of the marvellous things the boy from Urbino was painting. Ancient philosophers wandered through vast classical backdrops expounding the nature of the universe, figures of inestimable beauty and grace who seemed to breathe again the air of antiquity. They argue, they teach, they read, they sit alone in melancholy contemplation. Apollo plays his golden lyre among the company of poets while the doctors of the church argue, with perfect equanimity, the meaning of the Eucharist. The message of the Pope’s library was clear: pagan antiquity and modern Christianity were not incompatible, but continuous.

Julius was so impressed, Vasari says, he gave over the whole suite of rooms that would become known as the Raphael Stanze to be decorated by Raphael alone. Raphael’s experience of fresco painting was very limited. He knew he couldn’t complete this great project without help, so he began to bring together the team that would become his family: Giulio Romano, Giovanni da Udine, Polidoro da Caravaggio (not that one) and Giovan Francesco Penni. They created a style of narrative combining drama and clarity, rhetorical set pieces and moments of intimacy, cinematic in its scale and scope. Visitors hurrying to the Sistine Chapel today pass through these rooms but often stop as though remembering something. It’s as if they’ve always known these images but needed reminding. They are the moment when the revival of ancient culture truly entered Western consciousness.

In the second of the rooms he decorated for Julius, Raphael painted Heliodorus driven out of the Temple in Jerusalem by angels as the Book of the Maccabees describes it: “A horse appeared to them with a fearsome rider and decked out with a beautiful saddle. While running furiously, the horse attacked Heliodorus with its front hooves. The rider appeared to be clothed in full body armour made of gold. Two young men also appeared before him – unmatched in bodily strength, of superb beauty, and with magnificent robes.”

Heliodorus, the agent of King Seleucus, has sought to steal the “widows’ gold” from the Temple. He falls forward into our space, a bronze urn tipped on the ground with gold coins spilling guiltily out. It’s one of Raphael’s most dramatic and violent scenes, a companion piece to St Peter’s liberation on an adjoining wall. Gold is the armour of the avenger and the sin.

Julius II died before Raphael completed this room, but the election as pope of the tubby, pleasure loving Cardinal Giovanni de’ Medici, son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, signalled a great shopping spree for Rome’s artists. He took the name Leo X. “Now that God has seen fit to grant us the Papacy,” Leo said, “let us enjoy it.”

Leo, who loved young men as much as his predecessor had, also loved Raphael, retaining him to complete the suite of rooms and to produce cartoons for tapestries to hang in the Sistine Chapel as well as countless other paintings. When the architect of the new St Peter’s, Donato Bramante, died in 1514, Leo appointed Raphael in his stead. Soon the artist was overwhelmed with work, relying more and more on his assistants to execute frescoes while he controlled the designs through drawings – sketches, figure studies and detailed cartoons.

A few months before Leo’s election, Michelangelo’s ceiling in the Sistine Chapel had been unveiled to universal astonishment, but some time earlier the young Raphael had had a sneak preview. It changed everything he thought about painting. Under the spell of the Sistine ceiling, Raphael’s figures became more solid, more dynamic, more powerful. Draperies no longer concealed the force of bodies beneath them. Michelangelo’s spectacular painted architecture, the grandeur of the Prophets and Sibyls, would also resurface in works Raphael began to design from then on, such as the impressive fresco of Isaiah in the Basilica of Sant’Agostino, with which he stole a march on the unveiling of the Sistine Chapel itself in October 1512.

And the young male nudes, playing like pagan gods across Michelangelo’s ceiling, put an idea in Raphael’s head. What if the ancient world which had inspired Michelangelo, with all its magnificence and beauty, its paradoxes, its harmony of thought and uninhibited love of sensuality, could come again?

He drafted a letter to Leo X with the help of Castiglione, begging him to put a stop to the destruction of Rome’s ancient buildings by modern building contractors. If Rome were to be renewed, she needed these vestiges of her past greatness to inspire her artists. In it he speculated on what was possible in the past and what was believed now:

“There are many who, on bringing their feeble judgement to bear on what is written concerning the great achievements of the Romans … have come to the conclusion that these achievements are more likely to be fables than facts. I, however, have always seen – and still do see – things differently … I do not find it unreasonable to believe that much of what we consider impossible seemed, to them, exceedingly simple.”

His purpose was to make what seemed impossible simple in his own work. If the Church was slow or squeamish about this this, there were other patrons who shared his dream. The immensely wealthy Sienese banker Agostino Chigi persuaded Raphael to decorate his villa by the Tiber, built to emulate celebrated ancient villas with extensive gardens and fine loggias dedicated to pleasure.

First Raphael produced a single superb fresco of the nymph Galatea riding a chariot across the sea drawn by dolphins. Castiglione would later forge a letter as if from Raphael describing how he imagined the figure of Galatea: “being deprived of good judges and beautiful women I make do with a certain idea which comes into my head. Whether this has in it some artistic excellence I don’t know; I certainly labour to acquire it.”

About four years later Raphael returned to Chigi’s villa, in 1518. Then he brought his entire team and beloved Margarita in tow to paint the ceiling of the garden loggia with the story of Cupid and Psyche. It’s one of the first and most complete renditions of the pagan world in the Renaissance. Between a painted pergola entwined with flowers and fruit, phallic golden gourds and yonic crimson pomegranates – a sly dig at Michelangelo’s grandiose architecture of the Sistine ceiling – nude gods and goddesses, with the gentle golden glow of the Mediterranean about their skin, tell the story of Cupid and Psyche’s trials towards true love: how Venus, jealous of Psyche’s beauty, sent her son to punish her, only for Cupid to fall in love with Psyche himself and wish to make her a goddess.

A magnificently virile Mercury seems to appear poised to land on the pavement of the loggia itself. The Graces listening to Cupid’s seductive pleas fuse realism and idealism, their sensually perfect bodies twine elegantly about each other while their cheeks blush – probably one of the few sections of the ceiling Raphael painted himself.

Jupiter kisses Cupid; Venus flies through the blue heavens in a chariot drawn by diminutive doves; Psyche smiles knowingly as she rises to Olympus in a gold dress that reveals more than it conceals.

This is the pagan world in all its sensual glory, unshackled from narrow medievalism, revelling in sexual love without inhibition. There is a serious tale to be told about the passage of the soul (psyche in Greek) through life’s trials, but Raphael tells it with such exuberance and through the medium of the nude, the spiritual world embracing the sensual. Indeed, the foibles of gods and mortals are celebrated equally.

Across the flattened curve of the ceiling’s apex the gods feast as if woven on a fictive tapestry hung like an awning above our heads. Beneath this scene, Chigi himself once feasted with the Pope to celebrate his marriage to his long-time mistress, the loggia open to the warm Roman night, with the scent of orange blossom from the gardens, lamp light flickering on the bright scenes above and the golden plates on which Chigi’s guests dined. In an act of infamous extravagance, after each course the plates were taken from the table and thrown into the Tiber, although the guests were unaware that Chigi’s servants had hung nets just below the water line to catch them. Chigi was no fool where gold was concerned.

Raphael got what he wanted from men of rank. A man of no family, a professional who would have been considered a mere labourer in the past, he subverted the old order of class and privilege

And nor was Raphael. By the time he came to work on this loggia, he had a thriving and profitable business designing tapestries, engravings, metalwork, chapels and palaces, as well as producing paintings for the Pope and close members of his curia. His team was working from his designs on the decoration of a tier of loggias in the Apostolic Palace, the papal residence, with motifs derived from recently discovered ancient fresco paintings in the Golden House of Nero. He was already constructing what was intended to be a vast villa in the hills above Rome, Pope Leo’s own Golden House with terraces, elegant dining rooms and intimate bathrooms. Princes couldn’t command Raphael. The Duke of Ferrara spent years begging, cajoling and threatening him via his emissaries for a work of art to add to his collection:

“We do not consider writing to Raphael of Urbino as you suggest, but we wish you to find him and tell him that you have received letters from us in which we write that three years have now passed since he gave us his word; and that this is no way to treat men of our rank.”

Instead, Raphael got what he wanted from men of rank. A man of no family, a professional who would have been considered a mere labourer in the past, he subverted the old order of class and privilege.

Vasari tells us Raphael insisted his lover be housed with him in Chigi’s villa while he worked there. Margarita, it seems, was also his model. Her face is the face of some of his late Madonnas, her body likely all over Chigi’s ceiling, so it’s little surprise he needed her there.

The Duke of Ferrara’s demands might have been ignored, but Raphael took the time to paint Margarita’s portrait twice, once half nude, the other in a beautiful gown of pale yellow satin embroidered with gold thread, the sleeve of which is fashionably slashed to reveal the white chemise beneath. It’s loosened a little, and she clutches it to keep it from slipping further. A golden veil covers her dark hair. Gold was the colour of a courtesan in Rome, and in her intense look is a recognition of belonging.

‘‘No court, howsoever great it be, can have any beauty or brightness in it, or mirth, without women," wrote Castiglione in The Book of the Courtier. Portraits such as this suggest Raphael respected women’s civilising influence, as well as loved them. The role of women – whether the Madonna, St Cecilia, Psyche or Margarita herself – seems central to his paintings in a way not seen before.

Blue

She sits in a meadow leaning against a tree stump; her blue mantle, ultramarine rising to lead white highlights, covers much of her body. If it is Margarita, she is idealised and rendered virginal in blue. She leans forward to touch the young St John the Baptist in a protective gesture. Her child, a beautiful boy with golden blonde curls, takes a makeshift cross from his cousin. Innocence in blue – blue which saturates the painting like wine. A blue sky only the Mediterranean can muster above their heads, and in the distance blue mountains and a lake. Even the Madonna’s meticulously painted sandals are made of blue leather.

Blue is everywhere in Raphael’s work, not just The Alba Madonna. It dominates the sky, the heavenly realm, in his St Cecilia Altarpiece in Bologna, for example. In Christ Falling on the Way to Calvary, it forms an arc of sympathy between mother and son as the Madonna, surrounded by dark reaches of red, stretches out towards the fallen Christ. It is the realm of purity, telling us what we’re looking at. And so the skies in St Cecilia, The Transfiguration and The Loggia of Psyche are all a lake of ultramarine, a pigment derived from crushed lapis lazuli, which was as costly as gold

Stories are told about Raphael because so little is known about his actual life. We have only a handful of letters by him, while several hundred by Michelangelo exist, along with his workshop records; several volumes of Leonardo’s notebooks survive. So, it’s little wonder Vasari relied on hearsay when researching his biography, and myths abound. We have many of Raphael’s artworks, which tell us something about the man, his love of gentleness in men and women, his passion for antiquity, his emotional response to beauty. And we have aspects of the image of the courtly, elegant, charming man his friends promoted. But all this is speculation without his words. And on most things, he’s silent.

So, we’re told anecdotes: how he came across a young mother and her two children in the countryside and immediately set about painting them on the bottom of a wine barrel, so charmed was he by the image. And how he put off the offer of marriage to a niece of Cardinal Bibbiena because he hoped for a cardinal’s hat himself. Even his death is mythologised. To “die like Raphael” in Italy means to expire during the act of lovemaking, which no one at the time suggested, not even Vasari.

Some stories ring true. We’re told of how Michelangelo encountered Raphael and a band of his adoring assistants in the streets of Rome one day. “Where are you going,” he asks of Raphael, “surrounded like a lord?” Raphael replies with his own question: “And you, alone like an executioner?” The contrast of the gregarious, easy-going courtier and the solitary, almost tragic Michelangelo may be after the fact, and with a foot in both legends, but his response rings true given Raphael’s puzzlement over Michelangelo’s determined isolation.

Baldassare Castiglione, the witty, erudite, brilliant wordsmith from Mantua, had been a friend of Raphael’s since they met in about 1503. His intelligent blue eyes gaze steadily at us from what is possibly one of the most beautiful portraits ever made. Castiglione wears black velvet with broad, fur-trimmed sleeves of a bluish grey, a tint that would be named after this portrait, Castiglione blue. He is, in the truest sense of the word, life-like: alert, inquisitive, alive, and the expression in those intensely blue eyes is friendly.

The influence of Castiglione on Raphael and Raphael on him goes much further than a stunning portrait. Why, for example, does Raphael’s art seem so effortless? In The Book of the Courtier, Castiglione had offered an answer, coining a new word. Sprezzatura, or “nonchalance”, an effortless grace that could be innate as well as learned, was the hallmark of the perfect courtier: “Therefore we may call that art true art which does not seem to be art.”

In the history of Raphael’s times, we remember the House of Borgia, the warrior Pope Julius, the brutal Sack of Rome, the treachery and bloodshed of the Renaissance. Raphael and Castiglione were in love with the idea of antiquity, a place of the imagination as thrilling and consoling as opening a new book. Raphael and his friends would make sweet picnic jaunts to the Roman countryside to sit among the flowers and the ruins of Hadrian’s villa and imagine the past. “Tommorow … I shall again see Tivoli,” the Venetian poet Pietro Bembo would write, “with Navagero, Beazzano, Castiglione and Raphael.” Everything was defined by ancient Rome, “the fatherland of all Christians and ancient mother of glory,” as Raphael put it.

It lasted barely 20 years, this pitch of High Renaissance – Raphael’s professional lifetime – and these few brief moments within it when the dream of pagan antiquity and the Christian present merged into an ideal coexistence were like a sweet illusion; moments captured on the ceiling of Chigi’s loggia or the rapture of St Cecilia, in blue skies and golden raiment.

The tensions implicit in such a melding of ancient and modern, pagan and Christian, the excesses of Pope Leo’s hedonistic court, the envy of foreign kings and the simmering rage of Martin Luther, couldn’t hold, and didn’t really outlive Raphael’s fatal illness in 1520

But these could only ever be moments. The tensions implicit in such a melding of ancient and modern, pagan and Christian, the excesses of Pope Leo’s hedonistic court, the envy of foreign kings and the simmering rage of Martin Luther, couldn’t hold, and didn’t really outlive Raphael’s fatal illness in 1520. Within days, Agostino Chigi was dead, and with a year Pope Leo too. Castiglione would follow at the end of the decade. The Reformation would come, and the Church’s reaction would eventually scorch the earth of any vestiges of what it considered to be pagan sensuality.

“Death was envious of one who could make the dead bones of ancient Rome live again,” wrote Castiglione. Raphael had already purchased a niche to house a tomb in the Basilica of Santa Maria ad Martyres, better known as the Pantheon. He’d be buried in an antique sarcophagus in an old pagan temple dedicated to all the gods. Bembo would provide an epitaph and the citizens of Rome would turn out to watch in silence their artist’s funeral cortege make its progress through the streets. They might do so out of duty for a king or prince of the Church. They did it out of love for the Prince of Painters.

Raphael would be worshipped by generations to come: Titian, the Carracci, Rubens, Poussin, Claude, the English academicians and the French revolutionaries, Turner and Delacroix; even the Pre-Raphaelites defined themselves in contradiction to him. But it was the form not the essence of Raphael’s work that the academies of the 17th and 18th centuries admired. The dazzling neopagan spirit became the father of a narrow academicism. His genius for narrative painting would be put to the service of propaganda. The 19th century found him sentimental. The 20th saw him eclipsed by Michelangelo’s tortured masculinity and Leonardo’s scientific enthusiasms.

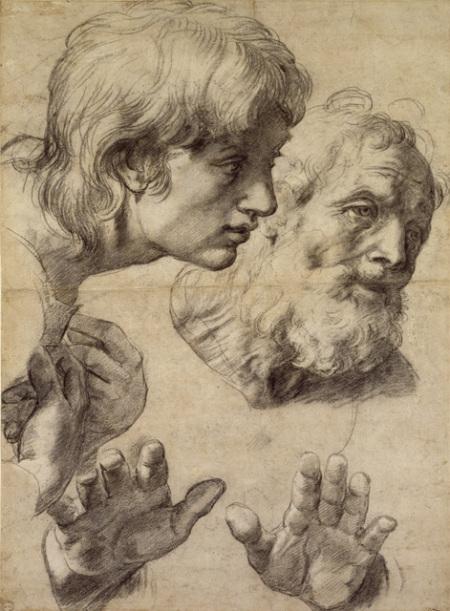

There is a drawing in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford – two heads, studies for two of the apostles in the lower part of The Transfiguration, are coupled with drawings of their hands, done in black chalk. In the painting they stand next to each other, youth and age contrasted, the younger man slightly overlapping his older companion. It is possibly Raphael’s greatest drawing, superbly executed by an artist at the height of his powers. The deft hatching with the chalk to denote shading and volume; the use of bare white paper in the highlights on the tips of fingers dramatising their eloquence; the strong, defining contours achieved by dipping the tip of the chalk in oil, a trick he’d learned from Michelangelo – these are all the techniques of a great draftsman. But this drawing shows something else: an instinct for beauty married to a deep understanding of psychology. If this one drawing was all that had survived of The Transfiguration, it would be enough.

Raphael had made this painting in competition with another artist, the Venetian Sebastiano del Piombo, who, it was common knowledge, had solicited the help of Michelangelo to make drawings for his piece, The Raising of Lazarus. Cardinal de’ Medici would judge which was the best painting. If there were a competition between the two artists, respectful or otherwise, did Raphael have the last word? He wrote to a friend at the time: “Michel Agnolo will see very clearly that I do not beat Bastiano … but rather himself, who is reputed (and rightly so) the Idea of drawing.”

The sheet in the Ashmolean shows, beyond a doubt, that Raphael too was the “Idea” of drawing. But beyond the areas of flesh the lines of black chalk peter out, leaving heads and hands floating.

Raphael’s body would be placed on a bier in the hall in which The Transfiguration stood, at the foot of the huge panel. Those who came to pay their respects could only wonder at what had been lost. Castiglione, Bembo, the ailing Chigi, Cardinal de’ Medici and, in the crowd that hung about in the street outside, Margarita Luti might all have looked sorrowfully up at the lights in the windows, a glimpse of Christ in that brilliant azure sky.

There is a pressure on his forehead. A thumb traces the sign of the cross; the rich, dark scent of myrrh fills his nostrils. He is tired. His breath so small it barely moves his chest. He cannot hear the words of the priest. He cannot move his limbs, and the world is shrunk to the candles flickering beyond his eyelids. Tin yellow shifting to ochre with madder lake at its centre. The flames dim and the azurite of the veins on his eyelids darken and expand to a rich ultramarine which soon takes the place of the glowing candlelight. Then this dims again to a deeper carmine purple, and finally to the deepest black.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments