Foster’s resignation places the Partition of Ireland on even shakier ground

British politicians tend to know nothing about Northern Ireland until it blows up in their faces – and Arlene Foster’s departure has made a political explosion more likely, writes Patrick Cockburn

The resignation of Arlene Foster as leader of the Democratic Unionist Party and first minster for Northern Ireland coincides almost to the day with the 100th anniversary of the Partition of Ireland on 3 May 1921. The coincidence is appropriate since unionism in Northern Ireland is in a state of general crisis and Partition looks shakier today than at any time in its history.

The union with Britain will not end soon and nor is Irish unity around the next corner but there is a historic change taking place in the balance of power between unionists and nationalists, Protestants and Catholics, the UK and the Irish Republic, and – the newest element – between the UK and the EU.

The departure of Foster is one important symptom of this transformation. Her serial unforced errors since she became DUP leader in December 2015 exacerbated existing trends that weaken unionism and Partition, but she did not create them and her successor will have to grapple with them.

The key question now is whether a new DUP leader will deliberately inflate the unionist sense of threat, which is never far from paranoia, to claw back the support of harder-line unionists before the Northern Ireland Assembly election in May 2022. This would then be fought on a straight sectarian basis between unionists/Protestants and nationalists/Catholics.

The DUP will argue that Partition, dividing Ireland into the two states of Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic, is under threat as never before, though in many respects it is their own intransigence that has undermined it. Again and again, Foster overplayed her hand in the five-and-half years that she was DUP leader, doing more damage to the union with Britain than Irish Republicans could have dreamed of.

A crude and unjust settlement in many respects, Partition had the advantage of settling The Irish Question for nearly half a century. Partition with a capital P became the short-hand word for the creation of two very different states. The biggest losers were the Catholics of the north, making up one third of its population in 1921. Isolated politically from the south by the new border, they were in a permanent minority, subjected to discrimination at every level, in a statelet run in the sole interests of the Protestant majority.

Partition was largely detested by Irish nationalists north and south, but there was not much they could do about it and it did, at least, bring about a sort of cold peace.

The 1921 settlement contained the seeds of its own destruction as a constitutional settlement, though these might not have germinated if the unionists had not excluded the Catholics from political power and economic opportunity. Northern Ireland was, as one British newspaper headlined it in the 1960s, “John Bull’s Political Slum”. Electoral districts were gerrymandered, the Royal Ulster Constabulary and the paramilitary “B” Specials were both overwhelmingly Protestant, while government jobs and housing were allocated on a sectarian basis.

The Irish Republic, for its part, is more prosperous, more secular and has greater international influence in the US and EU than in the past

The system was unsustainable, but when the inevitable explosion came it was not over the issue of Partition, but over the demand for political, social and economic equality within the Northern Ireland state.

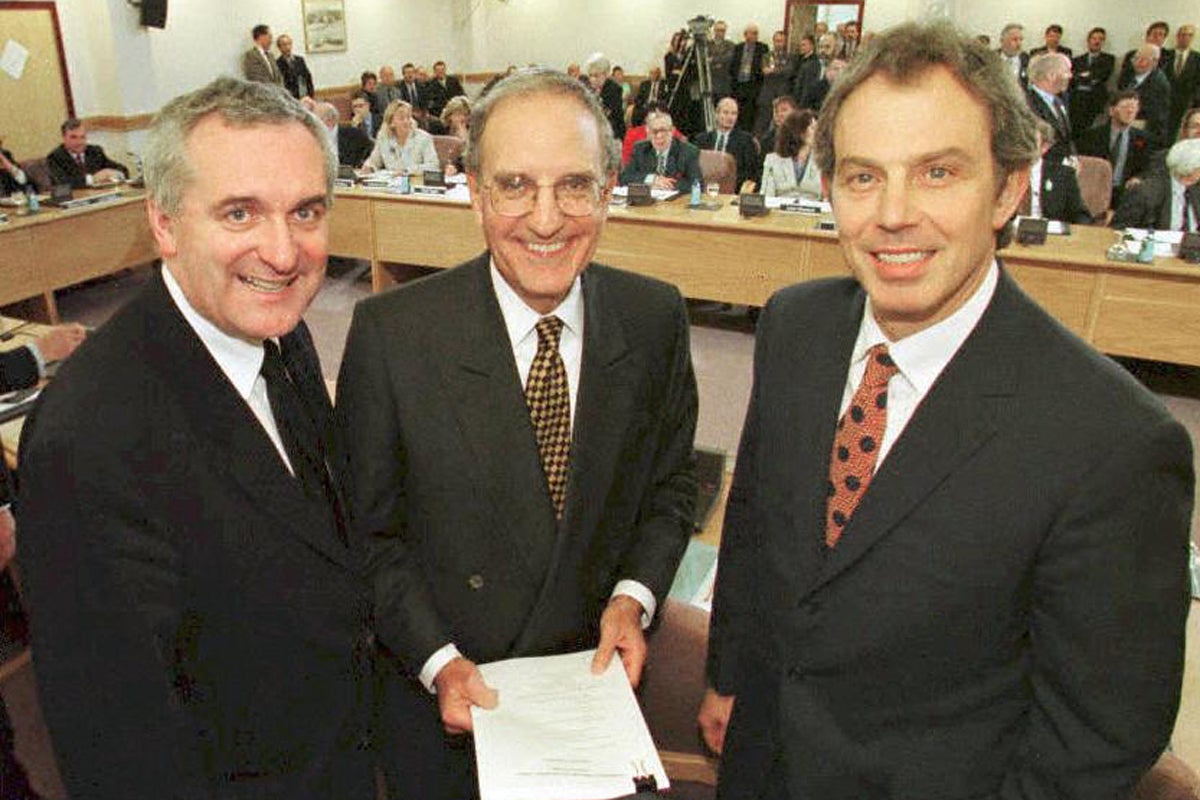

Militant republicans and unionists might tell it differently, claiming from diametrically opposing angles that the conflict was all about the maintenance or destruction of the union with Britain, but this was never the case. The low-level warfare known as the Troubles lasted from the first civil-rights marches by Catholics in 1968 to the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) of 1998. The agreement recognised what should have been obvious 30 years earlier, that there are two separate communities, unionist/Protestant and nationalist/Catholic, in Northern Ireland, each with their own distinct identities, interests and loyalties.

The GFA sought, with a surprising degree of success, to accommodate both communities within an accepted set of rules that looked both west-east across the Irish Sea towards Britain and north-south across the border towards the Irish Republic.

The line on the map denoting the border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic remained just as it had been since 1921. But the nature of the border, and of the division it embodied, was transformed as what had once been one of the more heavily fortified frontiers in Europe was dismantled.

Travellers crossing it no longer found the road ahead closed by concrete blocks or were funnelled through a limited number of military checkpoints. People living in a former IRA stronghold like south Armagh were no longer under the permanent surveillance of military watch towers.

The GFA sought to recognise realities on the ground that were much changed from what they had been 30 years earlier in 1968, and differed even more radically from those of 1921. What nationalists had described as “the Orange State” – in which they were second-class citizens deprived of civil and economic rights – no longer existed. It was not buttressed any more by the British army and security services which had unwittingly acted as the chief recruiting sergeants for the Provisional IRA.

The IRA did not win its armed struggle for an end to Partition and the creation of a united Ireland, but nor did it lose it or look like doing so. Contrary to the British government claim that it was a tiny group of terrorists without popular backing, the IRA had at least the political support – going by election results – of about a third of the nationalist population in the north, which was enough to sustain its pin-prick military campaign.

Beginning with the hunger strikes in 1981, the IRA found that the electoral opportunities for Sinn Fein, its political wing, far outstripped its military prospects. The calculation turned out to be correct. A crucial feature of the political landscape in Northern Ireland today is that Sinn Fein routinely gets about two-thirds of the nationalist vote in elections, something that may make it the largest party in the Assembly elections in May 2022.

As one local commentator put it: “Nationalist voters like republican politics much more than they like republican violence.” The new balance of power between the two communities is driven by short- and long-term developments. When Partition was first introduced, Protestants were two-thirds and Catholics one-third of the population in the north, but the current census – the results of which are to be announced in 1922 – is likely to show that the numbers are now about equal, with Protestants and Catholics each numbering about one million, the Catholics probably in a small majority.

Where do these complex political convulsions leave Partition? The divide from mainland Britain is weaker and the connection with the Irish Republic is closer than it was

Social and economic change has disproportionately hit the Protestant working class, which once dominated industrial employment in the shipyards and engineering factories. As in the rest of Britain, these jobs have largely disappeared, while Catholics are increasingly better educated and predominant in the universities and professions.

The Irish Republic, for its part, is more prosperous, more secular and has greater international influence in the US and EU than in the past. The American role in opening the door to the GFA is often underestimated and British governments have always been acutely aware of the impact of what they do in Ireland on their relations with the US.

This is particularly true with President Biden, known for his pro-Irish sympathies. All sides purport to revere the GFA, referring to it as if its status was somewhere between holy writ and the Magna Carta. Practical support for it is more equivocal. Foster and the DUP, which dominate unionist politics in Northern Ireland, never liked it and have done as little as possible to share power with Sinn Fein as their partners in government. The interests of the Protestant community might have been better served by seeing the GFA as shoring up their position rather than weakening it.

Adamantine intransigence on the part of unionists, typified by the slogans “No Surrender” and “Not an Inch”, once automatically produced political dividends. But that time has passed. The Orange Card is not what it was because Protestant Ulster can no longer be presented as the first line of defence of the British empire. The DUP blames Boris Johnson for betraying them over the Irish Protocol, but his actions show that the unionists of Ulster can no longer expect to be backed by the Conservative Party.

The GFA might have had the long-term staying power of the Partition settlement had the UK not voted to leave the EU in the referendum in 2016. British politicians tend to know nothing about Northern Ireland until it blows up in their faces. Johnson and the proponents of Brexit never gave any thought to the impact of turning the Irish border – a frontier that scarcely existed except as a line on the map thanks to the GFA – into the only land border between the EU and the UK. Suddenly Partition, something which Irish nationalists had been vainly trying to make an international issue since it first divided Ireland, became a problem discussed by world leaders in Brussels, Washington, Paris and Berlin.

Misjudgements by the DUP over the past five years will one day be the subject of a PhD or some other form of academic study on the disastrous consequences of overplaying a political hand. First the DUP supported the Leave campaign under the impression that it would make Northern Ireland more British and restore a “hard border” with the covert intention of weakening the GFA settlement. It was a naïve miscalculation and, in any case, Northern Ireland voted strongly to remain in the EU. Foster and her DUP colleagues never took on board that the UK needed a withdrawal agreement more than the EU and was never going to torpedo it for the sake of the Ulster unionists.

Instead of strengthening Partition as the DUP had imagined, Brexit has wounded it, perhaps mortally. For a few glorious years from the DUP point of view, the old alliance between the unionists of Northern Ireland and the Conservative Party seemed to be reborn. Between 2017 and 2019, Theresa May’s government depended on DUP votes for its majority. DUP leaders were flattered by invitations to Downing Street and obtained the respectful attention of the British media.

It was an illusion. Foster and her colleagues mistook temporary and accidental influence for real power. They double-downed on the mistake by trusting the blandishments of Johnson in the naïve expectation that as prime minister he would stand by them.

What they got instead was the Irish Protocol with a commercial border running down the Irish Sea and no barriers between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic. In the Executive, the DUP ended up simultaneously denouncing and implementing the Protocol, which loses it votes both to the hardline Traditional Unionist Voice and to the moderate Alliance Party. The recent riots across Northern Ireland show how the political temperature is rising and will get hotter still as the DUP seeks to shore up its position as the prime champion of unionism.

Read More:

Where do these complex political convulsions leave Partition? The divide from mainland Britain is deeper and the connection with the Irish Republic is stronger than it was. Political support for unionism has eroded. Post-Brexit, fewer Catholics in the north want to stay in the union and the same is true of a smaller number of Protestants. Unionism is visibly in crisis, but unionists do not know what to do to reverse the trend.

Yet crucial aspects of the political landscape have not changed since 1921. The bedrock of Partition was the wish of the majority of the Protestant community to stay within the UK and outside a united Ireland – and that determination is, for a large part, still what it was. But by treating every change as an existential threat to unionism, it is the DUP that is destabilising Northern Ireland and putting the future of Partition in doubt.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments