How to turn a fashion blogger into a political activist

Reihane Taravati made a video celebrating happiness. It went viral. For this she faced imprisonment and 91 lashes. Borzou Daragahi explains how Tehran makes enemies of its own people

She was “Happy”, one of a group of carefree Tehran youngsters dancing to Pharrell Williams’ hit song in a viral 2014 video clip. It showed a bright, colourful and upbeat vision of Iranian youth dressed in fashionable clothes and grooving to pop rhythms on rooftops and alleyways. It was a vivid, vibrant contrast to the grim pictures of Iranians living under the dark repressive shadow of the autocratic clerical regime that had ruled the country since 1979.

The then 22-year-old Reihane Taravati and six of her friends made the video with no budget or expectations But it became an overnight internet sensation. It quickly racked up millions of views, with thousands of comments on social media.

“We saw lots of people all over the world making videos of ‘Happy’ but no one from Iran had made one,” says Taravati, explaining in an interview from Tehran how she and a group of friends, photographers and filmmakers, made the video. “We didn’t think about the consequences for a second. We thought it would be something between us; we never imagined it would go viral.”

Then the regime cracked down. Within days, security forces purporting to protect Iranians’ moral virtues tracked down the young men and women who appeared in the video and its director. After a global outcry, Taravati and the others were released. But that would not be the end of it. Now on the radar of the regime’s gremlins, she’s been harassed, surveilled and in and out of the clutches of the security forces ever since. Goons in the employ of the Iranian authorities have rummaged through her personal belongings. Her small marketing business has been crushed. Old friends shun her as a possible collaborator. And she now faces a new set of charges and a possible prison term.

Through it all, Taravati has been transformed. Ironically, her treatment at the hands of the regime has politicised her, showing how the government’s ham-fisted responses to those who violate its unwritten mores creates its own enemies. Over the years, her Instagram page, once devoted almost exclusively to fashion and fun, has shifted toward politics and activists. Pictures of rights defenders and rebel icons have replaced those of models and clothes.

“When they stormed into my house, I thought that there’s nothing in this nation called home,” she says. “From that point on I was freaked out about them coming after me. You start to see that it’s happening to those around you, and you become sensitive. You feel closer to those this has happened to, those who have been in prison, and you start to think about how they’re being treated.”

Taravati’s seven-year travail also encapsulates the disappointments of the era under President Hassan Rouhani, whose eight years in office end this June. “Happy” hit social media in the months after Rouhani was elected Iran’s president in a surprise first-round victory over several more hardline candidates in 2013.

In the final days before the vote, the avowedly reformist candidate dropped out of the race and endorsed Rouhani. Iranians in the country launched a last-minute social media campaign urging support for the white-turbaned UK-educated politician, who trounced his four opponents with slightly more than 50 per cent of the vote.

Iranians poured into the streets in celebration, hopeful of an opening of the country’s tightly constrained political and social atmosphere after eight years under the presidency of the toxic, radical rightwing Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Rouhani, a mid-ranking cleric, appeared buoyed by the show of support from Iran’s women, youth and ethnic and religious minorities, and vowed to pursue their interests and aims. He immediately got to work easing relations with the US in what would eventually lead to a deal on Iran’s nuclear programme, and vowed to increase social freedoms.

“Obviously, economic problems and foreign policy are important, but these won’t stop us from thinking about cultural issues and domestic politics,” he told the Financial Times in a 2013 interview. “I am seeking to devise a civil rights charter. I will complete this charter after receiving the views of intellectuals and experts and will present it to the society and will pursue its enforcement.”

Many young Iranians like Taravati – who graduated from Tehran’s prestigious University of Art in 2013 – took such promises to heart, believing that, finally, change in Iran was afoot. Following the new president’s inauguration, dozens of human rights activists and defenders were released from prison. Many within the political elite, even the conservatives adopted the government’s rhetoric of compromise with the west. Rouhani vowed to respect people’s personal lives.

“A strong government does not mean a government that interferes and intervenes in all affairs,” he told a group of clerics in 2013. “It is not a government that limits the lives of people. This is not a strong government.”

But on the ground, elements within the regime’s security forces and hardline paramilitary forces were already preparing their comeback. They had resented Rouhani’s rise, and sought to maintain their grip on the nation. And they were confused and angered by Iranians turning to social media channels such as Instagram and YouTube. They struggled to find ways of using such tools to propagate their own messages without allowing them to become centres of resistance. Between 2016 and 2020, at least 100 Iranians were arrested for posts on Instagram, according to human rights monitors.

“There was a genuine fear they were losing the moral compass of Iranian youth,” says Mahsa Alimardani, an Oxford researcher with a focus on internet usage and censorship in Iran. “Iran is reckoning with this phenomenon. It hasn’t figured out what to do. Its power is so useful for the system and there are many Islamic figures and politicians making use of Instagram – but the way they are trying to deal with it is through fear.”

The loud banging on the front door of Taravati’s apartment came at 10pm just two days or so after ‘Happy’ had gone viral

The loud banging on the front door of Taravati’s Tehran apartment came at 10pm just two days after “Happy” had gone viral. As Taravati peered through the peephole, she spotted a woman who claimed she was the wife of one of her neighbours and needed to be allowed in. Taravati opened the door and a swarm of men poured into her flat, knocking her across against the walls.

“It was very scary,” she recalls. “They were accusing me of being one of the ‘Happy’ kids. They started shaming me about the clothes I was wearing in my own apartment.”

They began ransacking her home, sorting through her drawers, dumping her belongings on to the floor. There might have been 30 men coming in and out of her flat for hours, she recalls. They included plainclothes law enforcement, uniformed officers and members of shadowy militias. They seized her television, some paintings she had made, her books and a pile of Vogue magazines.

“Why do you read Freud?” she recalls an officer asking.

They searched through her clothes, including her underwear. “Why did they bring my clothes out? I don’t know what can be in my clothes,” she says.

She was handcuffed and taken to a police station. They seized her phone and began calling other members of the “Happy” team, falsely telling them she was sick and in need of their help at the police station, where they too were arrested once they arrived. In jail they were treated harshly, offered disgusting food and placed in rough conditions.

Tehran’s police chief announced they had been arrested for an "obscene video clip that offended public morals and was released in cyberspace”. But news of the arrests quickly spread around the world. Human rights groups and political leaders spoke out, and even the American singer Williams condemned the arrests. “It is beyond sad that these kids were arrested for trying to spread happiness,” he wrote on his Facebook page.

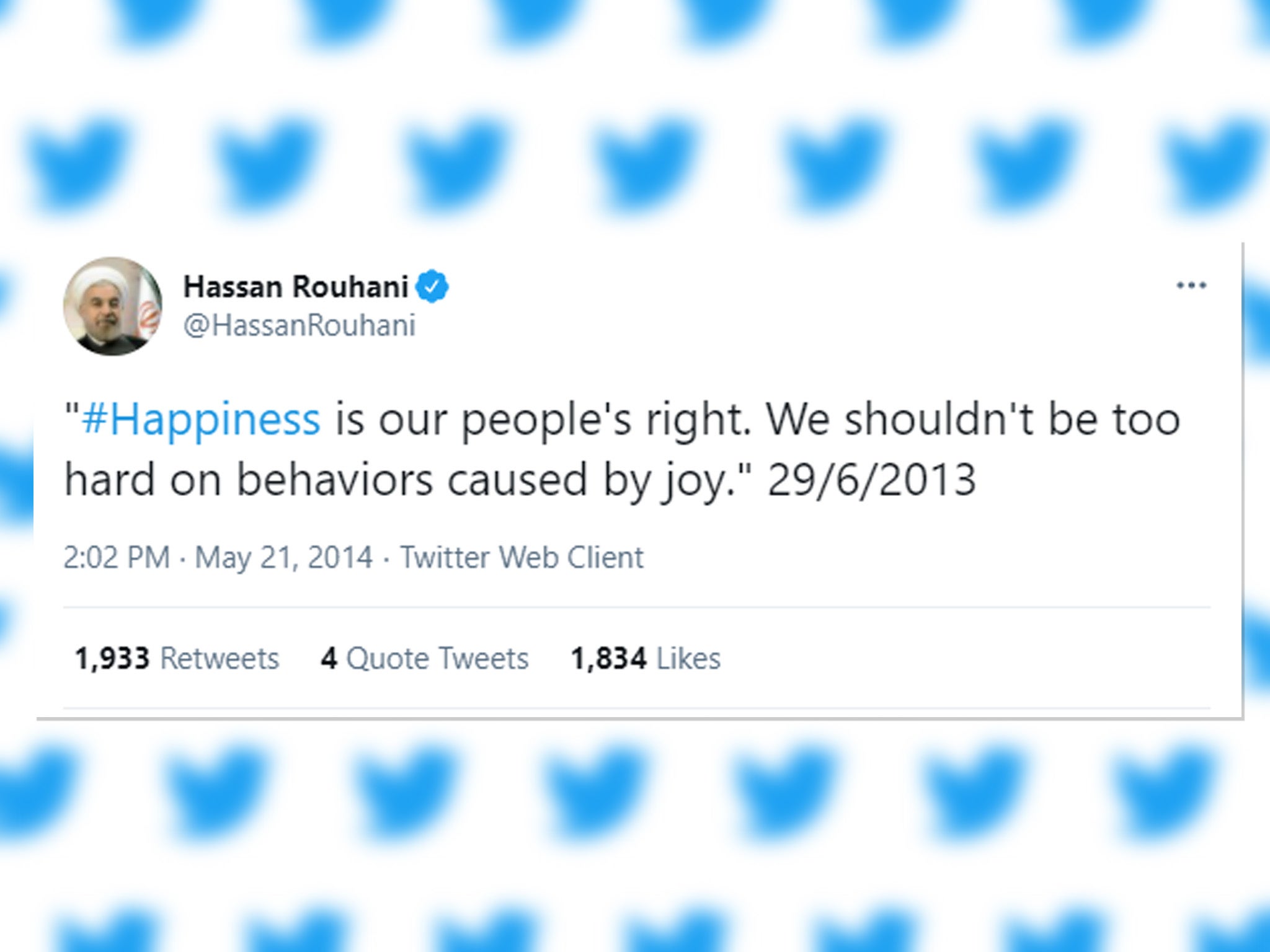

Rouhani, too, weighed in, posting a tweet quoting himself from the previous year saying, “Happiness is our people’s right. We shouldn’t be too hard on behaviours caused by joy."

Suddenly, the security forces’ tone shifted. “In the final 24 hours they became nicer,” she recalls. “They said, ‘You’re a good girl.’”

They brought her fresh fruit and hot tea. “They said, ‘don’t do any interviews when you leave’. And I didn’t. I posted something on my Instagram saying, ‘thanks for campaigning for me’, but I didn’t do any interviews.”

Some of them were forced to appear on state television, and apologise for their actions as if they had handed over military secrets to an enemy nation rather than make a video set to the music of a catchy pop song. A few months later she and the rest of the “Happy” team were handed sentences of one year in prison and 91 lashes, but the punishments were suspended so long as they stayed out of trouble for three years.

Amnesty International called the charges absurd, unjust and ludicrous. “These individuals will have been convicted and branded criminals purely for making a music video celebrating happiness,” said Hassiba Hadj Sahraoui. “The youths should never have been paraded before state TV to ‘confess’ nor brought to trial.”

Her home was sealed off with police tape for two months, as if it was the scene of a homicide rather than a lively start-up

Taravati sought to move on, but the experience had a profound impact on her, she says. It got under her skin and entered her nightmares “This is the side effect they want,” she says. “They want you to be paranoid all the time.”

It took her years to rebuild her life and get her career back on track and to put the “Happy” episode behind her. She became more active on social media. She started a small marketing studio, running promotional campaigns for Iranian clothing and consumer companies. Gradually, she built it up to 15 employees working on and off on various campaigns. And over the years she built up her presence on Instagram, where she has amassed 220,000 followers.

But unbeknown to her, she remained on the radar of the security forces, and in July of 2019, they came for her again. This time Taravati was out of town when they poured into the north Tehran design studio that now doubles as her home. She began receiving frantic calls from her colleagues. Reihane, they’re here! They have a warrant. They broke down the door. They are hurting people. They’re taking away everything.

“They detained everyone,” she says, her voicing brimming with rage. “They searched everything,” she says. “They broke a lot of my stuff. It was just like what happened with ‘Happy.’ They pour into some place, with a very big team so that you’re frightened, and they confiscate everything: papers, DVDs, CDs, books, movies and they put them in plastic bags and take them away. Maybe they won’t even look at them. It’s mostly for scaring people.”

Taravati struggled to find her colleagues and get them released, and it took her days to find out what had happened. It turned out that a hardline Islamic group had lodged a complaint against her based on fashion shoots her firm had been doing on the rooftop.

“They were fashion photographs showing clothes and jackets with heads cropped out. It was for the commercial work we were doing,” she says. “But they called the photographs ‘nude photos’.”

They also found some bottles of alcohol, an illegal but common commodity kept in most Iranian homes, and suggested that the marketing firm she was running was some kind of den of iniquity.

Her colleagues were allowed out of jail after posting stiff bails. Eventually the authorities realised they had nothing. “They saw they were arresting a bunch of 20 years olds, and they were crying,” she says. “We’re not a news agency or a political party with hardened activists. No one expected this.”

Eventually, charges were dropped against everyone except her, who was described as the ringleader of a house of corruption. Her home was sealed off with police tape for two months, as if it was the scene of a homicide rather than a lively startup. “I had to sneak in just to get my cats out,” she says.

They were fashion photographs of clothes for the commercial work we were doing. But they called the photographs ‘nude photos’

With renewed US sanctions crushing the economy, and hardliners ascendant, the last few years have been harsh on Iran’s middle class. Many of Taravati’s friends and even her close relatives have emigrated to the west. Taravati’s life has grown especially difficult, with pressure from the authorities and suspicion from her old friends and colleagues.

“You get it from this side and you get it from that side,” she says. “People say that Reihane went in, and got out. Maybe she’s an informer. You get pressure from that side and then on this side they said she’s collaborating.”

Last year she suffered two bouts of what she was told was coronavirus, and it has made her weaker and more fragile. She speaks of the grey hairs that have sprung up. Still, Taravati says she prefers to stay in Iran and fight as tough as it is. “I believe that people should stay here and work here and do something for our country,” she says.

She’s not alone. Since “Happy”, the regime has lashed out repeatedly against young people dancing in videos, including the case of Instagram star Maedeh Hojabri, who was forced to appear on state television and confess to violating moral codes. The government has also cracked down on schoolchildren making upbeat videos showing people dancing. “I believe there are political motives behind the incidents,” education minister Mohammad Bathaei was quoted as saying by local news outlets in 2019. “The enemies want to undermine people’s trust in schools.”

Taravati and her lawyer have an uphill battle in court, where she faces a possible prison sentence of six months in prison and a stiff fine. During one recent hearing at Tehran’s infamous Revolutionary Court, the judge refused even to allow her into the courtroom, permitting only the lawyer to enter. The lawyer insisted the judge take a look at his client, before he proceeded. Finally the judge relented, allowing her into the hearing room.

“I am running a small business that provides jobs for young people,” she says with pride, recounting what she told the judge. “I brought in teenagers and trained them and created jobs. I gave them salaries and skills. And then you came into my home when I was not there?”

She told the judge: “If it were anywhere else in the world, I would be celebrated.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments