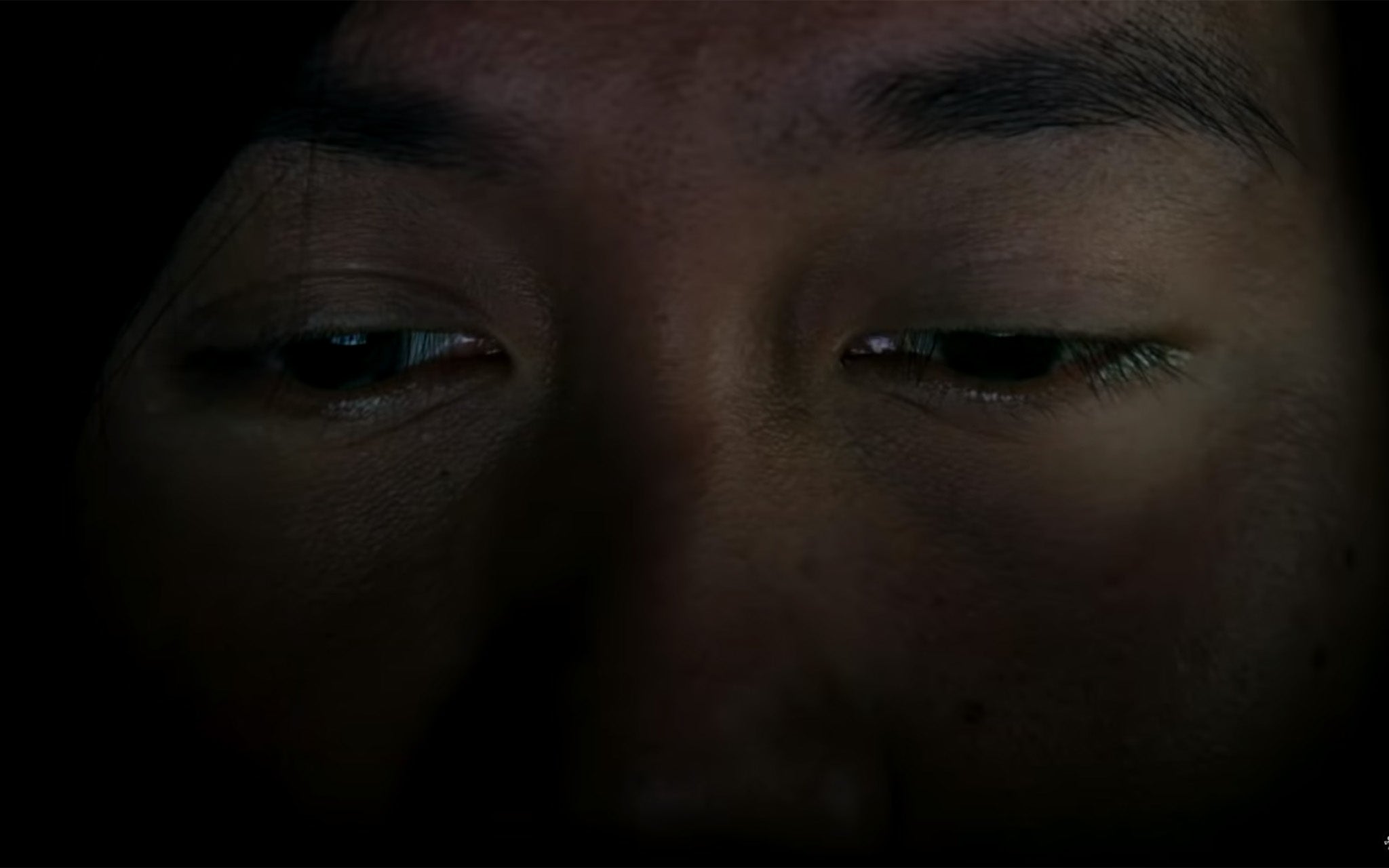

‘It’s a dirty little secret’: The mental health crisis among the internet’s content moderators

As social media platforms grow ever larger, so too has the army of people employed to filter out the most gruesome and extreme content posted to them. The human cost is often great, writes Greg Noone

Horror films were no longer convincing for Max. They seemed timid in comparison to the heinous material he watched daily as a content moderator. Max – not his real name – found the workload heavy, but manageable. By the time he would eventually leave his job reviewing video as a contractor for a major social media platform, so many flagged clips were being deposited through his inbox that the review process for each could only stretch to 30 seconds.

Most of them were benign, mistakenly flagged and easy to filter out. Once in a while, though, the worst of it – an animal abused, a head disconnected – would play peekaboo in the lineup. Over time, Max grew jaded, his skin a little thicker. Occasionally, the worst images would continue to flash in his memory, at great cost to his personal life.

“This one time my girlfriend and I were fooling around on the couch,” before Max’s girlfriend made an innocuous joke and he shut down the conversation. “I doubt, maybe a decade down the line, maybe I will stop encountering these things that bring it up, but who knows?”

If you’ve ever flagged something offensive or disturbing on Facebook, YouTube or Twitter, it will almost certainly have been sent to someone like Max. Every day, millions of videos, status updates and images are reviewed by teams of moderators around the globe, patiently sifting through batches upon batches of material to find and delete signs of graphic violence, sexual or animal abuse, racism and pornography.

Sometimes, these individuals are gig workers, clicking through image after image from the comfort of their own homes. Many more are to be found sitting at rows and rows of desks in anonymous offices in Silicon Valley, Florida, Morocco, Manila or Bangalore.

Scattered reports suggest that the psychological impact of long-term exposure to images of graphic violence is devastating, with many content moderators reporting symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), paranoia and political extremism. These same reports suggest little in the way of mental health support. Despite this evidence, however, there have been few, if any, formal psychological surveys in this area on people like Max.

“There’s no longitudinal study that I know of that has tracked these individuals once they are out of the employ of these firms,” Sarah Roberts tells me. A professor of information studies at UCLA, Roberts interviewed moderators like Max for her book Behind the Screen. That social networks have not bothered to investigate the psychological impact their content can have on the moderators they employ is, she believes, out of a sense of wilful rather than genuine ignorance. “Not knowing means plausible deniability of responsibility, to a certain extent.”

Commercial content moderation – a term coined by Roberts – has been around almost as long as the internet itself. Its promise as a medium for the free exchange of information and ideas also implied its abuse, a theory that rapidly became reality in the 1990s as popular forums like LambdaMOO became embroiled in sexual harassment scandals. This is no less true for the social networks of today.

“These companies rose to prominence on a premise, sometimes implicit but many times overt, that what they were offering was an unfettered mechanism for people to express themselves,” explains Roberts.

The existence of a social network, however, is only made possible by advertisers paying to access the vast consumer base of people choosing to express themselves on that platform. This, says Roberts, explains both the reason for and the nature of the relationship between these platforms and content moderators: it is an exercise in brand management, and one that is to be talked about as little as possible.

Advertisers would refuse to engage with social networks if they became known as breeding grounds for racial hatred, violent imagery or hate speech. Employing hundreds if not thousands of content moderators to winnow it out of their platforms is, therefore, the most expedient way of threading the vision with the reality of social networks, but not one that they are keen to promote.

Most content moderation is reactive. Content thought to be offensive and therefore in violation of a site’s rules is flagged. Depending on the website – in addition to social media platforms, media outlets and e-commerce sites also employ moderating teams on a smaller scale – this material will go through a set of automated filters to check for obvious signs of pornography and copyright violations, before landing in the inbox of a dedicated moderating team, usually outside contractors.

At MegaTech, the pseudonymous social media platform where Max worked, the process of working through flagged videos quickly became rote. Videos are broken down into a string of 30 thumbnails and sent to moderators in groups of 10. After surveying the images for signs of animal abuse, graphic violence or pornography, among other things, Max would start on the next batch. A typical day would see him moderate up to 2,000 videos.

Like Max, most of the screeners Roberts interviewed for her book were bright young twentysomethings straight out of university. They considered the job well paid and, for all its proximity to the likes of Twitter, Facebook and YouTube, prestigious. “For many people, what they saw in this job opportunity was, ‘I’m going to be working in the tech industry’,” she explains. “And that’s where things fall down.”

What many of these recruits discovered was an extremely demanding role with little in the way of pastoral support or prospects of advancement. Most content moderation work is kept at arm’s length away from the platforms requiring it, outsourced either to freelancer networks like Amazon Mechanical Turk, boutique firms in the website’s country of origin, or dedicated call centres in India and the Philippines.

A few contractors, like Max, are brought literally, if not legally, in-house to work in the social network’s headquarters. Even then, their lower status in the company is confirmed by their exclusion from certain privileges. “This is the stupidest thing in retrospect, but there was a rock-climbing wall in the lobby,” Max told Roberts. “We couldn’t use it because we weren’t on the company insurance plan.”

More serious was the absence of pastoral care for content moderators. At MegaTech, counselling was treated as an afterthought. Moderators were left to develop thicker skins, which seems to have reinforced a culture of cynicism around the mental health sessions that were promoted by management. Many succeeded, or at least gave the outward appearance that they had. The workers Roberts spoke to often denied that they experienced any long-term impact on their personal wellbeing.

“I had no reason to think otherwise when people would say things like that,” she explains. “But you know, somewhere down the line in the interview, after a period of time, that same worker might say to me, ‘Since I’ve taken this job, I’ve been drinking a lot. I find myself opening a beer as soon as I get home.’” Others are reluctant to socialise with friends, for fear that the conversation might turn to work, while some – like Max – find the worst material they’ve seen intrude into their lives as disturbing flashbacks.

“I’m careful to differentiate between what these workers deal with psychologically and what workers who are in physical danger deal with,” says Roberts. Even so, “when you’ve had some kind of psychological damage done, it’s very difficult to put barriers up and leave it at the office, as it were, even though a lot of people would tell me that’s what they would try to do. But I don’t know how one does that.”

None of the workers Roberts interviewed said they were comfortable with talking about what they had seen with friends and family, not only because they were reluctant to expose them to harmful material or remind themselves of it, but also because many had signed non-disclosure agreements prohibiting such conversations.

“It goes to the point that these practices were treated, on the one hand, like trade secrets,” explains Roberts. “But I also think it’s because it was a dirty little secret towards the public.”

Despite this, workers like Max have some measure of pride in what they do. “They had a sense that they were doing something to the benefit of the greater good and on behalf of people who, unfortunately, didn’t even know they existed, much less the work that they did,” says Roberts. “So, while they had this real sense of pride and altruism, it was kind of diminished by the fact that their work was erased and invisible.”

The looming prospect of their jobs being outsourced to India and the Philippines didn’t help either. During Max’s time at MegaTech, many of the more routine screentasks – deleting pornography, for example – were diverted to teams in these countries. “They paid me a decent amount, and it was still miserable,” Max told Roberts. “I can’t imagine doing it for nothing.”

The reality is a little more complex. While moderators in India and the Philippines are certainly paid less than their American counterparts, many consider the role as the first rung of a potential career in the sector. When Sabrina Ahmad was researching content moderation in India for the Oxford Internet Institute, she found herself interviewing screeners who had already been doing the job for one company or another for up to five years.

“A lot of them said, ‘This is a career for me’,” says Ahmad, not only because it is seen in India as a stable profession, but also one with real prospects for advancement. “People are getting promoted, which in of itself is a very big thing, and they get to work with the internet.”

Even so, content moderators in India and the Philippines are expected to work much harder than in the west, given the fragility of the contractual relationships at stake. Shift work is commonplace, as firms alter start times of their workforces to adapt to the moderation needs of clients in Europe and North America. It isn’t unusual to see content screeners spill out of offices in downtown Manila to take advantage of happy hour at a nearby bar – at 7am.

For the screeners Roberts interviewed in Manila, the message was clear: “If you don’t meet the metrics, if your accuracy is poor… we will lose the contract and that will affect all of the workers,” she explains.

None of these workers are immune to the effects of the imagery they are required to vet. Counsellors for moderators in the Philippines have reported symptoms of PTSD, and Indian screeners have complained of long, stressful hours, completely incommensurate with their base salary.

Change has been promised by social media platforms – what shape it will take remains to be seen. In 2017, Facebook announced its intention to dramatically increase its army of moderators from 4,500 to over 20,000, and invest in artificial intelligence research to lighten the load on human shoulders even further.

Outsourcing content moderation to machines is, Roberts says, the ultimate desire of Silicon Valley’s brightest minds. Unfortunately, it’s not going to happen any time soon.

“We know [human moderators] are engaged because of their sophisticated ability to judge and to make meaning and to have nuance, and to do all of that in a split second,” explains Roberts. “And computers just can’t equal that.”

Currently, AI is really only useful in select moderation scenarios. “It’s really good at dealing with material that already exists in the world,” says Roberts. “When there’s known bad material that gets recirculated, it can successfully find and rescind that material very quickly, before it really is even up, per se.”

Even so, Roberts believes that this will at best only result in a hybrid combination of human and machine analysis. After all, there’ll always be a job for someone to train the algorithms.

“And I actually think that is to the benefit of most people, to have humans involved in vetting these tools,” says Roberts.

Meanwhile, the other solution – throwing more bodies at the moderation problem – does little in itself to alleviate the psychological trauma inflicted upon moderators. What, then, should be done?

Greater provision of mental health support services in moderation firms is a no-brainer, says Roberts. Treating these workers with the dignity they deserve is another, according to the moderators she interviewed. “The first thing they say to me – it should come as no surprise – is ‘Pay us. Pay us properly,’” says Roberts.

Internet companies should also remember that their responsibility to their moderation workforce does not end with the termination of their employment. “Figure out what people need over the long-term, when they are out of [the job] but you have fundamentally changed them in the course of having employed them,” says Roberts.

Some have waited to receive adequate compensation. A class action filed against Facebook in California last year cites the social network as having inflicted PTSD on moderators after it “bombarded” them with detestable content.

Moderation at the scale currently being performed could decline: the growth in encrypted messaging apps like WhatsApp suggest a retreat among younger demographics from public social media into private groups with private cultures. The need for some workforce though, exposed night and day to graphic content, is unlikely to disappear.

As well as imbuing Roberts with a renewed admiration for this new digital underclass, the experience of writing Behind the Screen gave her an unwelcome initiation into the sheer range of disturbing behaviours human beings are capable of. She recalls one particularly depressing conversation with an ex-content moderator for a news site whose comment sections had to be regularly scrubbed clean of homophobic, racist and sexist slurs.

“At the end of that interview, she described herself as a ‘sin eater,” says Roberts, a figure in English folklore who consumed the sins of a deceased neighbour by eating bread passed over their body. Conversations like this made her question how much the architecture of the internet itself and its uncanny valley of a public commons has given deviants a new stage on which to dance.

“The question becomes, to what extent are these systems themselves encouraging more and more debased, prurient, abhorrent content, which – frankly – is a representation of behaviour,” says Roberts. “I find that disturbing, all the time.”

‘Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media’ is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments