A web of deception: The strange tale of the $50,000 insect heist

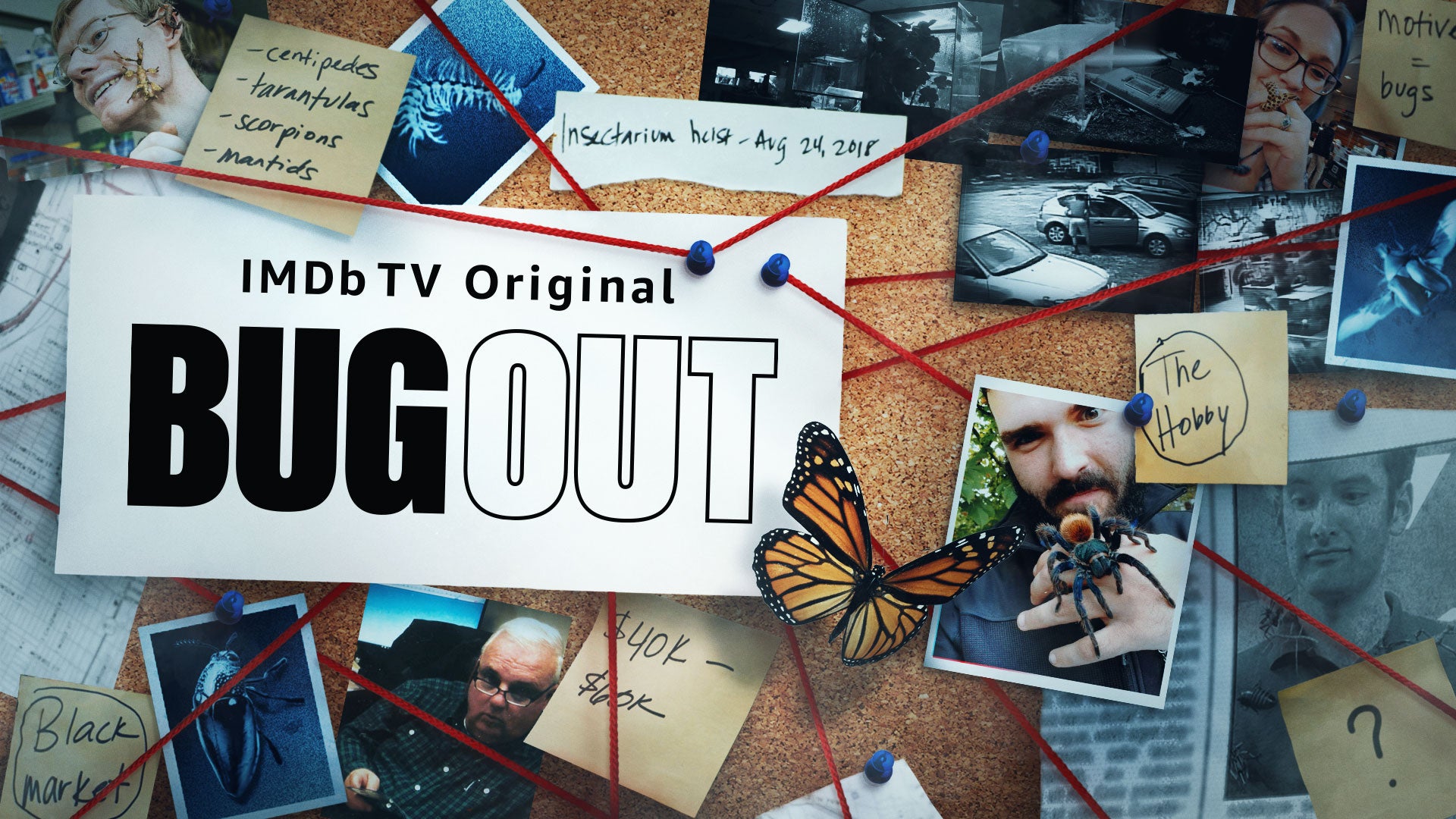

‘Bug Out’, an engrossing new four-part documentary on IMDb TV, shines a light on one of the oddest cases in the annals of crime, which plunged detectives into a little-known and perilous underworld. James Rampton speaks to those involved

Michael Zanetich, a detective with the Philadelphia Police Department, recalls the most bizarre case of his career. “We’ve investigated everything here from petty thefts to robberies, homicides and rapes. We’ve pretty much covered the whole gamut. But I’ve never investigated anything with bugs before.

“Some thefts are strange, some domestics are strange, but I don’t think there’s anything as strange as bugs being stolen. Who on earth reports that their bugs were stolen?”

Zanetich is referring to what is surely one of the oddest cases in the annals of crime: the notorious story of the “bug heist”. On 24 August 2018, a staggering $50,000 worth of living bugs were stolen from the Philadelphia Insectarium and Butterfly Pavilion – the first creepy-crawly zoo in the US.

The robbers took 80 per cent of the insectarium’s entire collection, amounting to some 7,000 bugs. All the felons left behind was a very threatening message: a set of electric-blue staff uniforms pinned to a wall with knives.

Eyewitnesses say that when this truly outlandish crime was reported at the police station in Philadelphia, detectives, “were peering over their cubicles going, ‘what’?” Zanetich’s colleagues mercilessly teased him about having to apprehend the fugitive creepy-crawlies. The investigating officers, like everyone else, were bugged out by this case.

In what was the largest theft of insects in history, the criminals took an astonishing array of rare creepy-crawlies with wonderfully evocative names, including desert hairy scorpions, domino cockroaches, giant African mantises, bumblebee millipedes, warty glowspot roaches, Mexican fireleg tarantulas, dwarf and tiger hissers, and leopard geckos.

The thieves even had the audacity to steal a six-eyed sand spider, the most venomous arachnid in the world. Its bite, which is often fatal and can cause 25 per cent of your flesh to rot, is as poisonous as that of a rattlesnake. Terrifyingly, no known antidote exists.

Before you could say “arachnophobia”, the heist became the subject of gags by late-night talk-show hosts – and the story instantly exploded right across the world. Responding to a concerned tweet saying, “if you see this six-eyed sand spider that is highly venomous, please let the Philadelphia Insectarium know”, Jimmy Kimmel joked: “Trust me, I’ll let them know, probably in a loud and very girlish scream.”

Supportive citizens donated thousands of dollars to the museum. Overnight, the staff also became local celebrities. Kevin Etheridge from the Animal Care Department at the insectarium, recollects, “I was on Tinder and people were like, ‘hey, I heard you're at the insectarium. What happened during that bug heist?’ I couldn’t get away from it.”

The story grew wings in the police station, too. According to Zanetich, “there were actually members of the police department suggesting that this six-eyed sand spider could be used in crimes and that it could be thrown at somebody in an act of terrorism.”

At first, this might have appeared a fun story. However, as Zanetich and his colleagues from the Philadelphia Police Department probed further into this weirdest of heists, they started to realise that the insectarium may not have been the “American as apple pie” family museum it purported to be. It was not wholly wholesome.

It shows how living cockroaches are used as jewellery in Madagascar and Hercules beetles are forced to fight each other for money in China and Japan

The detectives were also quickly plunged into a little-known and perilous underworld of villainous dealers in rare insects. The police discovered a thriving black market in exotic insects, part of a global trade in illegal wildlife that is worth an astounding $20bn a year. It is a proliferating crime that carries hefty prison sentences. It is a particularly dangerous type of flea market.

Although police suspect the bug heist was an inside job at the insectarium, they have been unable to muster sufficient evidence to charge anyone because insects are ridiculously easy to hide. So the crime remains tantalisingly unsolved.

The extraordinary story of this unbelievable heist is now recounted in Bug Out, an engrossing new four-part documentary that begins on IMDb TV on 4 March. Described by its director Ben Feldman as “Tiger King meets Ace Venture Pet Detective,” the series attempts to unravel the web of deception and obfuscation surrounding this story. It portrays the world’s most unconventional whodunnit, where the bounty has several legs and can give you a lethal bite.

Delving deep into the very unusual world of insect obsessives, it puts a magnifying glass on the worldwide popularity of bugs. It shows how living cockroaches are used as jewellery in Madagascar and Hercules beetles are forced to fight each other for money in China and Japan.

Bug Out covers every aspect of the creepy-crawly kingdom, scuttling from shady dealers in rare insects, bug-runners and embezzlement to death threats, honey traps and Mexican criminal cartels.

Jenner Furst, the executive producer of Bug Out, realised immediately that this yarn would make a tremendously enjoyable documentary. “People saw the bug heist headlines and said, ‘who the hell would want to steal bugs’? Everybody loves a good crime story and a whodunnit, but this was stranger-than-fiction in every way imaginable.

“This is the type of story that leads you into an unexpected place – one that makes you laugh, but also invites you to learn something about a world you would have never found on your own.”

Feldman, who was working as a lawyer in Philadelphia at the time, says he too was instantly captivated by the story of the bug heist. “I thought, ‘that can’t be it’. And indeed when I first met John Cambridge, the CEO of the Philadelphia insectarium, that was exactly his first comment to me: ‘there is so much more to this story than just the headline.’

“On that first day, he started telling me the whole history of the museum and some of the conflicts between different characters there. And I just thought, ‘all right, I think we’ve got something here’.”

The fact that many of the museum staff seemed determined to sink their teeth into each other certainly made the story all the more juicy. For instance, Cambridge was engaged in a lengthy legal dispute with the insectarium’s founder, ex-cop Steve Kanya.

It very quickly descended into a vicious blame game. “Things got heated,” Feldman admits. “There was a lot of conflict between these people and some really high stakes.”

The director was finally sold on the idea when he went to a bug collecting conference – yes, they really do exist – in Arizona in the summer of 2019. “During the day, everyone presents papers on bugs, and then at night they drive hours out into the desert and set up these huge white traps.

“The bugs come from miles away and land on this big sheet, and all these people are collecting them and out there having a really good time. It’s just had a blast. If you go to the conference, you will not be disappointed. If it’s not already there, put it on your bucket list now.”

He’s got this huge Mexican tarantula-breeding facility, and he purposefully sells these spiders at a loss to undercut the poachers who were driving native tarantula species towards extinction

The sheer scale of the creepy-crawly industry took the filmmakers aback. It is an immensely lucrative trade. For example, a single stag beetle can cost up to $100,000. Furst outlines why people are prepared to pay such high prices for rare bugs. “Insects are some of the rarest creatures on the planet.

“Some of them have habitats so exotic that the normal person could never experience them in the wild. It makes sense that people would pay unthinkably large sums of money to hold them in their hands.”

Pretty soon, though, the documentary makers became aware of the darker side of the business. Brent Karner, a bug salesman, says, “trying to understand the collectors’ mentality probably requires a psychology degree.

“There are those people in the world who will do anything to make sure they can get their hands on something like that, and that’s when the black market gets rather nefarious.”

As Jim Maxwell, a former FBI agent turned private investigator who helped the Philadelphia Police Department on this case, puts it: “Some people collect thimbles and some people collect bugs. You’re always going to find someone willing to pay almost anything if they want it bad enough.”

Feldman learnt more about this extremely dodgy netherworld through a chance encounter with a bug runner. “He opened up to me right away about how he’s made millions running bugs from one country to the next. That’s when I started to realise, ‘OK, there is big money here, and that always attracts some shadier players as well’.”

Not long afterwards, the director ran into another character you couldn’t make up, a man making a brave stand against the murky black-market traders in creepy-crawlies. “Some of the regulations can be an impediment to trading bugs internationally. But in the third episode, we go down to Guadalajara, Mexico, and spend some time with this guy, Rodrigo, who’s on the opposite side of that.

“He’s got this huge Mexican tarantula-breeding facility, and he purposefully sells these spiders at a loss to undercut the poachers who were driving native tarantula species towards extinction. Mexican tarantulas are the cream of the crop in the tarantula world, and Roderigo got really concerned because he was seeing these endangered spiders being sold in all these markets.

Essentially, the director carries on, “poachers were paying farmers to collect tarantulas on their land for pennies and then selling them for hundreds of dollars on the international market. So Roderigo took on these organised crime groups by undercutting their trade.”

How did these gangs, not known for their peace, love and understanding, react to Roderigo’s actions? “He received death threats, and things did get really dicey for him.”

Another detrimental effect of the illegal trade in insects is that non-native species can cause devastation in a new environment. Feldman explains, “there are some really high stakes at play here, not just because some of these species are endangered, but because some of them pose serious ecological risks.”

“Where so much of an economy is still based on agriculture, when certain insects are brought in, they can really disrupt the ecosystem and really wreak havoc on that industry.”

Some of the characters depicted in Bug Out are very unorthodox, to put it politely. In one quite remarkable scene, bug collector Kelvin Wiley walks into his bedroom, opens his mouth, and out crawls a tarantula. The message? Don’t try this at home.

Feldman details the filming of that scene. “I knew Kelvin did that sometimes for his Instagram feed. So I asked him to do it. But we had a monitor set up in a room next door for some of the crew, and they did not know it was coming.

“And so when Kelvin walked in and did that, you could hear an audible gasp in the other room. Afterwards, a bunch of the crew were coming up to me saying, ‘holy whatever, you have got to give us some heads-up. That was terrifying’.”

All the same, the filmmakers were was anxious not to take sides. In fact, if anything, they found themselves attracted to the unalloyed passion that the bug collectors displayed.

According to Furst, “the power of a good documentary is that you discover people who are deeply passionate about things you had no idea existed. It’s infectious, and we ultimately learn to love and care for things we never thought we could, just from watching others.”

It is true that the documentary should help raise awareness about how vital insects are to our very survival

Feldman chips in that, “it’s fascinating to try and figure out why people love collecting exotic creatures. That’s partly what makes Tiger King so fascinating: why are some people just drawn to these kind of dangerous and exotic animals and why do they spend their life trying to breed them, while other people are so grossed out by bugs?”

Some collectors are clearly in the grip of an unquenchable fixation. “We heard from some of the investigating authorities, like the US Fish and Wildlife Service,” Feldman continues, “that some people become so obsessive about collecting insects or whatever wildlife that consequences just don't seem to deter them.

“They get locked up, and then they get out and immediately go back to the trade – not even because they’re selling these creatures for the money, but just because they are obsessive about them.”

Like those mythical criminal masterminds with an unrivalled secret gallery full of old masters, bug collectors are also motivated by a desire to acquire something that no one else has. The director says, “when you get into the world of rare butterflies and rare beetles that can go for $100,000 a piece, I do think that’s part of it – ‘I have something you don’t’.”

For all that, Feldman confesses to a passion for the passionate. “Just being with people who are passionate about anything is a good energy to be around. It's inspiring. If they are passionate about something I don't understand, it's intellectually stimulating as well.

“I love that there’s something for everyone out there. Even if bugs aren’t my thing, I love the fact that there’s this whole world of people out there who are collecting these things and posting on the internet about them. That really lights my fire.”

Making the documentary has even persuaded Feldman to get up close and personal with bugs. “I got more comfortable holding a tarantula. I don’t think that’s something I would have done before this project. But now I’m like, ‘OK, this isn’t so bad’.”

Despite Feldman’s protestations, many people will take a lot more convincing before they want to cuddle a creepy-crawly. The director reflects that we are hardwired to be frightened of bugs. “I did speak to an entomologist about this issue.

“He said just that we’re evolutionarily trained to pay attention to skittery movements because they can be a threat. So when creatures move quickly and in that skittery-type motion, our brains are tuned to pick that up and be on alert – even though we don’t need to be scared of those things.”

The director adds, “70 per cent of the named species in the world are bugs. If we don’t come into contact with them that often, when we do, we try to brush them aside. So there is real value in taking a closer look at them.

“Some people might say, ‘I’m afraid of insects, so I’m not going to watch Bug Out.’ But I would say to them, ‘you should watch it because so much of what we fear is what we don’t understand. You get to learn about how essential these insects are to our environment, and by learning that, you can overcome some of the fear you have’.”

It is true that the documentary should help raise awareness about how vital insects are to our very survival. “From a very young age,” Cambridge says, “we are taught to fear insects or at least to think that bugs are gross – just look at TV and movies”.

“That’s a shame because it’s important for people to realise how reliant we are on insects and the ecosystem services they provide, like clean water, decomposition and pollination. Bugs are nature’s little workers, and we take them for granted in our day-to-day lives. We want to teach people to appreciate them.”

Furst trusts that Bug Out might also make us more conscious of how our rapacious behaviour is putting insects in peril. “The urgent subtext is that habitats are disappearing and our environmental abuses are making these magical creatures go extinct.”

Finally, what do the filmmakers hope that audiences will take away from Bug Out? “If we can learn to love these unexpected creatures through a wacky and entertaining whodunnit docuseries,” Furst replies, “hopefully we can learn to protect them from poachers and a rapidly changing planet. Because if we don’t, rare insects will only live in people’s homes, on our TV screens, or in our imaginations.

“Their days in the wild will be over forever.”

‘Bug Out’ begins on IMDb TV on 4 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments