‘I was 10 years old when I first sensed that something wasn’t right’: The trauma of a family secret

A decade ago, an extraordinary and unexpected event set Fiona Chesterton on the path to writing a book about being an illegitimate child

You learn to live with secrets. After you’ve harboured one for the best part of 30 years, as I did, it gets easier to keep it locked up inside. My mother, who kept the same secrets until her dying day, believed that it was for the best to keep – well – mum. No doubt her family, who I have only recently discovered also knew the truth, thought it for the best not to talk to me about it, believing they were respecting mum’s wishes too.

It took an extraordinary and totally unexpected event 10 years ago to set me on the path to writing a book, talking on the radio, and now writing this essay, unlocking those secrets at last. I am already learning of a remarkable outcome – that talking about my experience of being an illegitimate child and the terrible impact on my mother’s life is opening up a lot more conversations than I anticipated.

I know from the response I am getting from readers and listeners that there are many people with similar experiences of secrets, shame, elaborate deceptions and cover-ups – and in the worst cases, cruelty and emotional abuse – all because they bore children out of wedlock, were themselves illegitimate, or witnessed something at close hand in their own family.

There’s something here, surely, that we need to talk about and come to terms with.

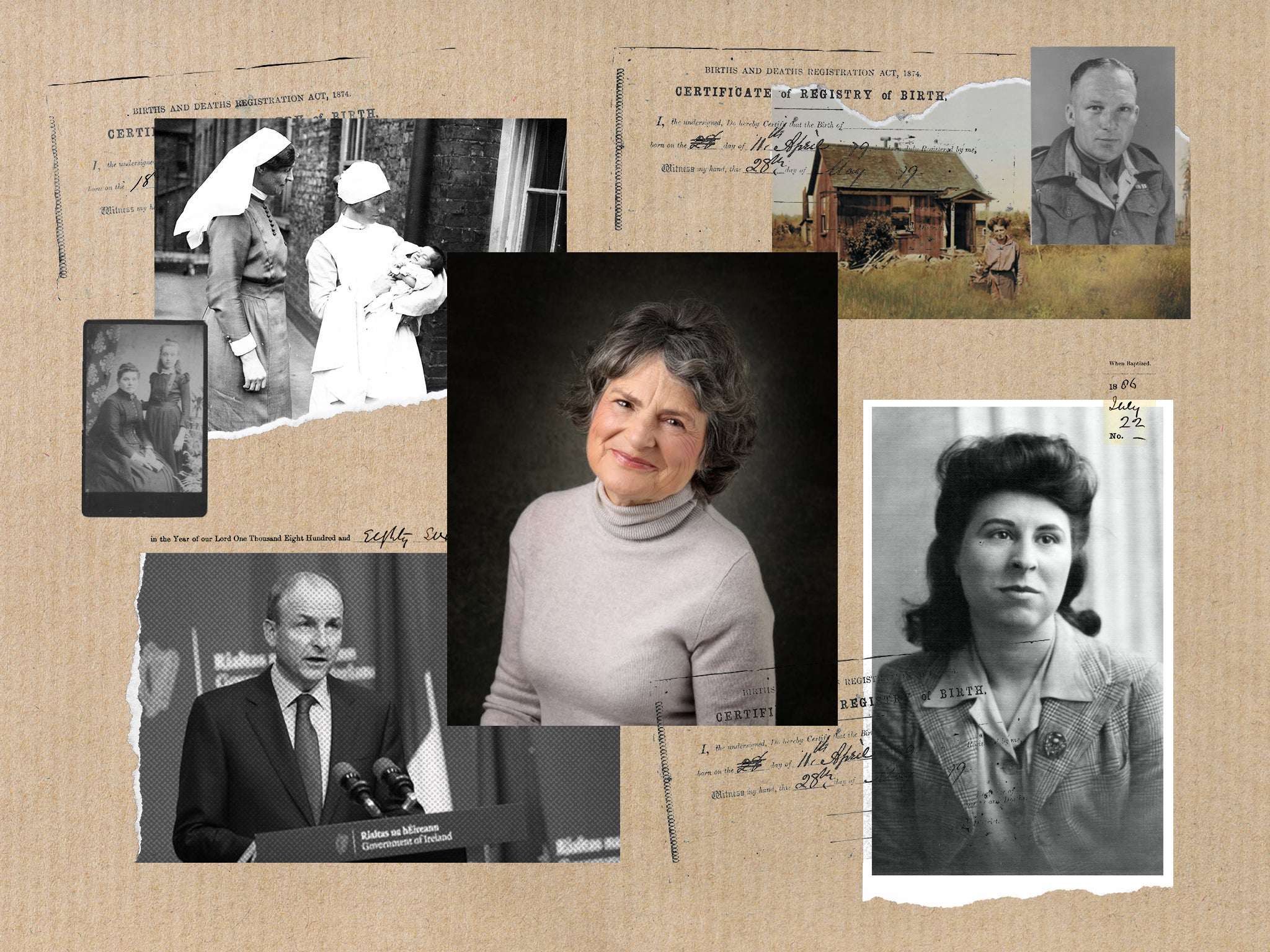

My epiphany started with an official letter from the Office of the Public Guardian of British Columbia, sent to me in my capacity as the administrator of my mother’s estate in 2011. It informed me that the estate was the beneficiary of a one-tenth share of another estate, that of a Canadian man called Underwood, who had died 17 years before. I had never heard of this man. It had taken the authorities all that time to discover anything of his identity, as he had no birth record, and the woman presumed to be his mother had also hidden her true origins.

Jessie Underwood, born Heading and also known as MacDonald, had emigrated on her own to Canada from England 100 years previously, just before the start of the First World War. I learnt from the Canadian official who had written to me (and who assured me the letter was not a scam and sent me a bank warrant for $35000 to prove it) that this was a tale of two generations of illegitimacy and cover-up.

I was intrigued to find out more, and a few years later started my own investigation, digging into records in Cambridge where Jessie Heading was born to the unmarried daughter of a Bedfordshire farmer. She was then given away to a widowed housekeeper, and was brought up for a life of domestic service. I discovered that shortly after her adoptive mother died, Jessie, still unmarried at the age of 35, signed up to an emigration scheme, which shipped thousands of female servants to Canada and other far-flung parts of the British empire.

Jessie, with just a few pounds in her pocket, knocked a few years off her age on her immigration papers. After seven or eight years in her new country she turned up in a rural community, which is now part of Greater Vancouver, with a five-year-old boy (who would become the man with no birth record). She married an elderly farmer, elaborating her new identity on her marriage certificate. She described herself as a widow called Mrs MacDonald, made up her father’s name, and stated that the Cambridge housekeeper was his wife and her mother.

All this was designed to disguise the fact that both she and the boy were illegitimate. No doubt Heading had discovered that the prejudices and taboos of Edwardian England, which she thought she had left behind, had been exported to the New World.

I found myself compelled to follow in the footsteps of Jessie – or Cousin Jessie as I now called her – and travelled to Vancouver to find out more. I realised that my empathy for this distant cousin came from my feelings for this woman, born out of wedlock, who had made a new life for herself.

When I learnt that Jessie and her boy may have been ostracised in their new home, and lived apparently isolated as well as tough lives, I realised that there were some uncanny parallels with my mother’s story and my own experience. Our life in Leicester in the 1950s and 1960s wasn’t as different as you might think from that of Jessie and her son in rural Canada 30 years before.

Mum told me of the fun, friends and dancing she had enjoyed in her twenties. I was too young then to realise that she was sinking into chronic depression

I was 10 years old when I first sensed that something wasn’t right, and that my family’s self-isolated and restricted life wasn’t normal. I convinced myself I was adopted. With hindsight, that was an ironic thing to fear, as indeed it was the fate of hundreds of thousands of children, born to unmarried mothers in the 30 years after the end of the Second World War, to be adopted – forcibly so in many cases.

Years later, when I had my own children, I discovered that the woman who had brought me up was indeed my birth mother, and that she had used legal means – and some petty deceptions – to pretend to be married. This, I now realise, ensured that she could keep me. Mum did not have to give up her child, as so many women did, but she still paid a lifelong penalty.

Mum was also no teenage unmarried mother – the stereotype of the time, described as “silly” or “wanton” girls who had “got into trouble”. No, my mother, born Mary McDonald (another coincidence with Cousin Jessie) was well into her thirties when she had me. She told me she had met my dad in Leicester after the end of the war a few years previously.

Mary had had a quiet war, working as a shorthand typist in the local hospital and in a factory, and was still living with her parents. My dad had served in the army, working as a mechanic and a driver, supporting the tank regiments as they battled their way across Europe to Berlin after D-Day. After they met, my parents moved away from Leicester, returning only in the months immediately before I was born. So far, so ordinary, you might say. Yet, as with Cousin Jessie, something changed – and not just Mum’s name – as I came onto the scene.

By the time I was 10 and beginning to understand the world, we were living in a house tied to my dad’s job. After a few years working as a salesman and a publican, Dad had become the manager of a working men’s club in Leicester. Meanwhile, Mum had become something of a recluse, hardly ever going out socially, let alone to the club next door. She had no friends.

This was not just keeping oneself to oneself, nor shyness – my Mum told me of the fun, friends and dancing she had enjoyed in her twenties. I was too young then to realise that she was sinking into chronic depression, which would lead inexorably to a breakdown. For a strikingly good-looking woman, she also suffered from a sort of self-neglect, wearing shabby clothes and never putting on make-up.

In my book I recall my memories of that time. In this extract, I lie in my parents’ bed, sick with the measles:

The big wardrobe – made of a browny-pink, shiny, composite material – and its matching dressing table might offer me some entertainment if I were allowed out of bed. Mummy keeps a beautiful hairbrush, comb and mirror set on the pearly table top, as well as a powder puff in a small china box and a cut-glass perfume bottle with a gold-tasselled spray handle. As the bottle is empty and the brush immaculate, this collection seems for decoration rather than use.

The wardrobe is full of possibilities too. On the left side, where my mother’s clothes are kept, there is a fur coat, several beautiful dresses and a suit, with a couple of pairs of high-heeled shoes and matching leather handbags.

I have never seen Mummy wear any of these alluring items. I know from reading her Woman’s Own that they are not in the current style, more in the New Wave fashion of a decade or more ago.

There are a few photos of Mummy in the drawer – smartly dressed, her raven-coloured hair styled, her face made up with powder and lipstick – but it feels to me as if that woman has been shelved, filed away along with the clothes here in this wardrobe.

I would never dare try any of them on, for fear of spoiling their pristine perfection. From time to time, I do risk trying on the shoes and teeter around the bedroom in them. Not now, though; the wardrobe doors are firmly shut and the daytime hours drag by more than the evening ones do.

My mum’s self-isolation extended to my life too. I could not invite schoolfriends home – ever. As an only child, I entertained myself – not even spending time after school with other children in the local park (the “reccy”, as it was called). On fine days, I might play alone in our unkempt back garden, which backed on to the railway line.

I was driven to a school across town by my dad, and weekends were also spent on my own. On Saturdays I had a private elocution lesson in town, to deal with a speech impediment, and maybe there would be a trip to town on the bus with my mum to visit the shops or the library. Occasionally I went shopping with my Dad – he often did the main grocery shop.

That was all. No Sunday school – we never went to church when that was much more the norm. No Brownies – Mum didn’t care for the organisation.

Sunday was spent for the most part at home with a good book or my homework, Hollywood films on the telly, and of course the Sunday roast – just the three of us, Mum, Dad and me. In the summer we had two weeks away at the seaside, the highlight of the year. Most of the photos I have from my childhood are taken on a beach or a promenade in some English seaside resort, with me wrapped up in a coat or jacket against the chilly North Sea winds.

As the Sixties progressed, I was transported out of my bleak surroundings by the new joy of pop music – with The Beatles tracking my teenage years. I was not unhappy despite my isolation. I loved school and did very well. My mum’s only happiness seemed to come from the vicarious pleasure of my success.

I never talked to my mum about what I had discovered – the marriage I learnt about in that lunch hour, but also another secret marriage years later

So my childhood memories are often curiously upbeat. It is not a misery memoir – at least, not from my childish perspective. Those memories now are filtered through my adult knowledge – the truth I learnt when I was in my forties, when Mum was frail and elderly. This is how I describe the impact of the first revelation:

Mum had another breakdown a while ago and she has had to go into a home. I had to clear her chaotic flat in a hurry and take a mass of papers to my house for safekeeping.

We – Howard, our two children and me – moved out of London a few years ago, in part to be closer to Mum in Leicester. We now live in a small village in Cambridgeshire less than an hour’s drive away. With work, commuting and family life, it takes me some time to get around to sorting out the drawer where I have stuffed Mum’s papers.

Among the random collection of bills, rent books, pension and bank statements, recipes cut out from magazines, old birthday cards, letters and postcards sent by us to Mum from our summer holidays in Portugal and France (I tear my hair out at her inability to throw anything away or file things in some sort of order), I found a large brown envelope.

I opened it and inside were a whole lot of important documents dating back years: birth, marriage and death certificates, a will and some other legal papers. Some were routine and familiar, some made my jaw drop.

They have turned my whole understanding of my family relationships upside down. They explain my childhood – at last. They are so devastating but, in some ways, unsurprising, that I can’t talk to anyone about them. Certainly not to Mum. She’s not well enough. They have to remain a secret a while longer. For one thing, there are still things to find out – lines of inquiry prompted by the evidence in the envelope.

That’s why I have embarked on this further quest, the one that I am now pursuing in my office lunch hour. I have ordered a record of a certificate of marriage up from the archive. It is contained in a heavy leather-bound volume, and I now stand with it open in front of me at a page recording the details of a wedding in Leicestershire some time before I was born.

The handwritten records set down here devastate me to the core. They confirm what I had suspected after opening that envelope and reading the contents, undermining the ground that I thought my childhood was built on. Now I realise it opens up new lines of inquiry – lines that I may struggle to follow. I certainly need some time to think about the implications of this wedding record, so I decide to leave it here for now.

I walk back to the office along the Embankment as I need some fresh air. I am rather good at keeping calm and carrying on but I need just a little more time to compose myself. I return to the office and get on with my work. I have given my customary sandwich a miss, though.

As I was to find out, truth – as well as love – hurts. There also can be unforeseen consequences when you pursue it. I never talked to my mum about what I had discovered – the marriage I learnt about in that lunch hour, but also another secret marriage years later. I know some might find that strange. Again, it was about respect, and the protection of a woman who was mentally fragile. In her last days, when mum was suffering somewhat from dementia, I realised that her insecurity about being unmarried with a child was not far from the surface of her unconscious – even though, outwardly, in the last years of her life, as a grandmother, she was the happiest I had ever known her to be.

My experience of the trauma caused by the deep-rooted prejudices against women who had children out of wedlock makes me understand and support those women who suffered forced adoptions and are campaigning now for justice – for recognition of the trauma they suffered – and, what is most crucial to realise, still suffer.

Maybe we should not be too comfortable about the robustness of our newer, more generous attitudes towards unmarried women and their children

They know that what happened to them in the Sixties, Seventies, and even into the Eighties cannot simply be consigned to the dustbin of history. That abuse – much crueller in many respects than my mum ever suffered – should not be dismissed lightly. The terrible cruelties inflicted on young mothers have now been well documented. Not just the forced adoptions, but the whole process of abuse, neglect and casual cruelty inflicted on them at every stage of the process, by teachers, nurses, GPs, midwives, social workers – and, of course, often their own families and neighbours.

In Ireland, the scandals of the mother and baby homes, in which unmarried pregnant girls and young women were incarcerated and humiliated with hard labour as punishment for their “sins”, have also been revealed in recent years. In some cases, we now know their babies were left to die as well. In January last year, the Irish prime minister, Micheal Martin, issued a government apology for the state’s complicity in this abuse.

In the UK, there are no precise statistics, but early evidence suggests that a high proportion of the women – maybe a third – who suffered forced adoptions did not go on to have further children. Although it is easier now for adopted children to find their birth mothers, reunions are rarely easy. The children who were forcibly handed over suffered their own trauma, believing their mothers had never loved them.

So the campaigners are looking to the British government to apologise for the treatment of the vulnerable young women they were when they were pregnant, when they delivered their babies – and when, shortly after, they were coerced into handing them over. They are not looking for financial compensation, although they are claiming funding for trauma counselling.

It is not an unrealistic expectation, as other governments, including that of Australia as well as those of Ireland and Flanders, have made similar apologies in the past few years. The Canadian Senate has also recommended such action from the prime minister, Justin Trudeau. Here, the parliamentary Joint Select Committee on Human Rights, chaired by Harriet Harman, is conducting an inquiry, and will soon be hearing evidence from some of the 300 women who came forward in the committee’s first stage of consultation at the end of last year. In Scotland, similar investigations are being conducted into forced adoptions. 2022 could be the year when there is significant progress towards the official apology these women are looking for.

Finally, another word of caution to those who might think this is just a historical issue, something that we have put behind us with all the other outmoded prejudices and cruelties. Let’s not be complacent. A recent article by Joseph Chamie, an independent demographer and former director of the United Nations Population Division, looked beyond our myopic British horizons with some sobering statistics.

Chamie was comparing the prevalence of births outside marriage in 1964 and 2014. Since the 1960s, in many – but by no means all – countries, there has been a steady increase in the proportion of children born out of wedlock, in tandem with the growing economic and social independence of women. In the large majority of developed countries, including the United Kingdom, Germany and the United States, by 2014 more than a third of all births took place out of wedlock. By contrast, according to OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) figures, there were still some twenty-five countries, including major ones like China and India, where the proportion of births recorded out of wedlock was as low as 1 per cent.

Significantly, in those countries, there is often still strong social disapproval of illegitimacy, including sanctions and penalties for the mother and father, as well as stigmatisation of the child... just as there was here for most of the 20th century. So our perception, living within what we like to call more progressive societies, that there are many acceptable frameworks for childbearing and long-term relationships, is far from the global norm. Even within the west, we see some signs of regression in women’s rights – for example on abortion. Maybe we should not be too comfortable about the robustness of our newer, more generous attitudes to unmarried women and their children.

I, though, am comfortable about one thing – that I don’t carry the burden of those family secrets any more.

Fiona Chesterton is a former BBC and Channel 4 producer, editor and journalist. Her book ‘Secrets Never to Be Told’ is published by the Conrad Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments