In memory of my best friend Ian Charleson, who performed the greatest Hamlet ever

Thirty years ago today the ‘Chariots of Fire’ star died of Aids. Fellow actor and best friend Hilton McRae recalls a man of stubbornness, bravery and brilliance

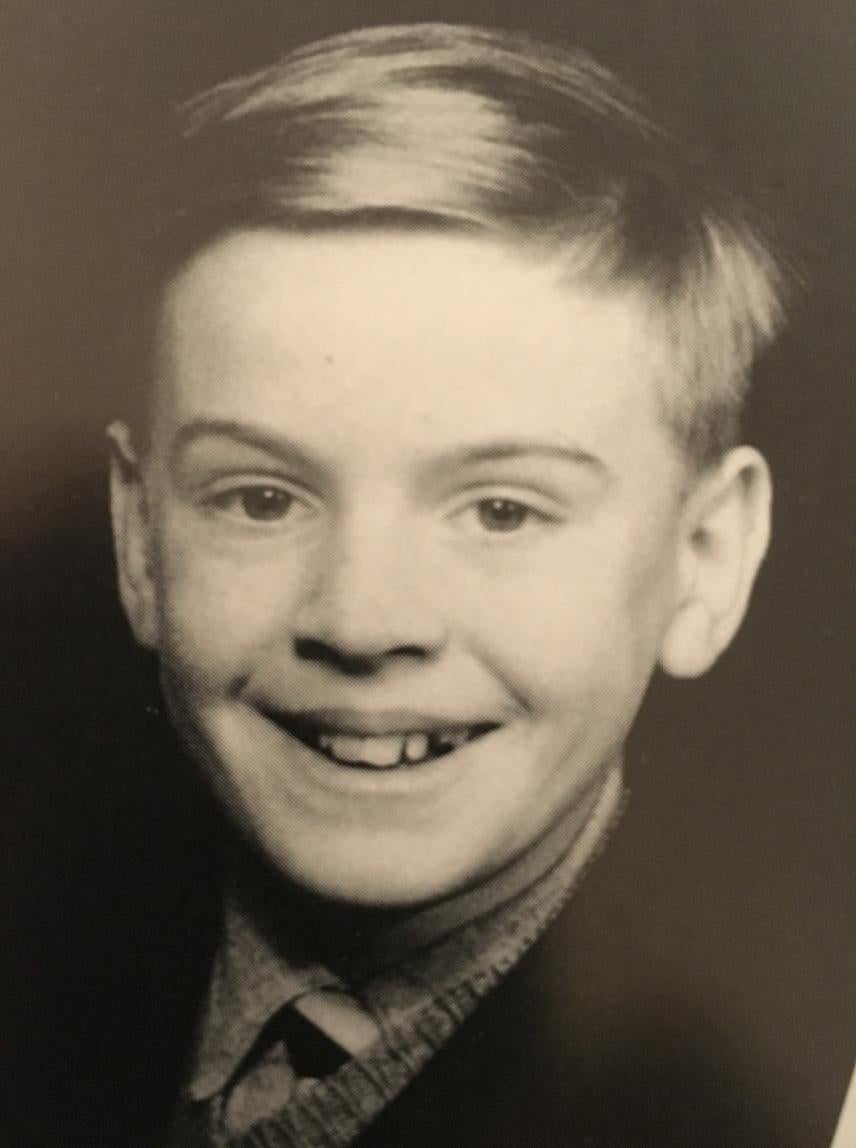

It was 1968. I went to Edinburgh University to read Scots law. My father’s best friend was the Sheriff of Dundee, so it seemed like a good idea. There was a scrap of paper on a noticeboard advertising lunchtime charades at Dramsoc’s premises. And that’s where I met Ian. A young man who looked old beyond his years, Ian McElhinney (Mac), performed a charade which I gathered to be a play by Shakespeare, and when Mac mimed tossing a coin, a blond god along the row from me exclaimed: “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.”

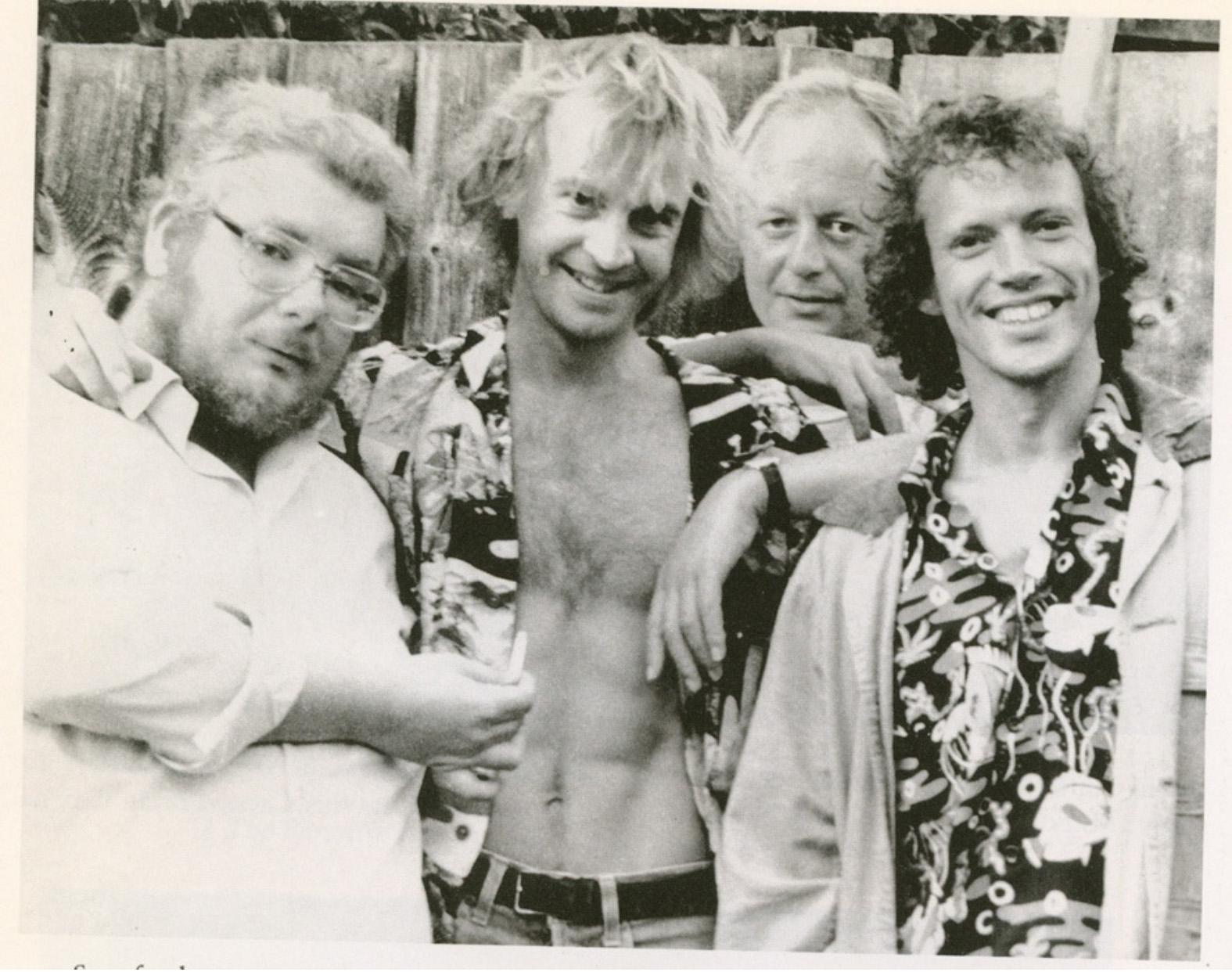

The blond god – tall, loose-limbed, beautiful but with bad acne – was Ian Charleson. During that first term we – Ian, Mac, David Wilson (now Rintoul) and myself – did a pile of plays, workshops, readings, whatever. When I went home for Christmas I told my dad: “I know what I want to do. I want to be an actor.”

“That confirms it,” he said, “you’re a fucking poof.” And that made me cry. Mac and I moved into a flat and hosted countless evenings of charades and bridge. And Ian would mostly be there. He was fun: gentle, caring, a dry wit. He would pick up his cards and mutter “fuck-my-old-boots’’.

One time we were having a cup of tea and knelt on the carpet, straight-backed, and he sang “My Funny Valentine” a capella. And time stopped. It turned out that his older brother Ken in his first entry in the Edinburgh Schools singing competition had won it singing “My Love Is Like A Red, Red Rose”. Their mum Jean –she was a member of the Communist Party after all – insisted that Ian, not Ken, enter the next year. He won, singing the same song, and the brothers won for several years, alternately.

Years later, before accepting Richard Eyre’s offer of Guys And Dolls at the National, he made Eyre listen to him sing the score, and when he’d finished he turned to the director saying: “You enjoyed that Richard, didn’t you?” And we all enjoyed it. He was a magnificent Sky Masterson, and every man and woman in the audience fell in love with him. In the summer of 1969, he designed the costumes for Sartre’s The Flies – having managed to fail his second-year architecture exam for designing a splendid bridge with no foundations.

Ergo, the actresses found themselves in dresses revealing their bare breasts. We did a late-night revue as well. I lodged with Ian at his parents’ home. Poor dad Jack had to let us in a few times at three in the morning. “An’ whit time dae ye call this?” Rintoul went off to Rada, Ian to Lamda. I completed my degree in ’72, moved down to London to work at the Hard Rock Cafe, and stayed with Ian just off Abbey Road. I got him a job at the Hard Rock as a busboy. He danced as he cleared the tables.

In his flat he had dozens of half-finished paintings, he would play me Mahler’s fifth – the adagietto, of course – declaring Barbirolli the best conductor of that piece. I learned so much in his company about music and art. All passed on with utmost consideration. Amusingly self-deprecating about his acting skills, he was graceful in movement and gesture. He told me about a speech he did for Brian Cox (another Dundonian), who was teaching at the college. “Very good!” said Brian. Then he tied his arms and legs to a chair and said: “Now fucking do it.” That was our first lesson on the power of the word.

Ian was terribly ashamed of his poverty. His colleagues at Lamda somehow got Alec Guinness to give him a wee cheque and a pile of hand-me-down clothes in an attempt to ease the penury

Ian was terribly ashamed of his poverty. His colleagues at Lamda somehow got Alec Guinness to give him a wee cheque and a pile of hand-me-down clothes in an attempt to ease the penury. One evening at the Hard Rock, Frank Dunlop, the director at the Young Vic saw him, chatted him up, and in no time at the end of 1972 he was in Dunlop’s Joseph and the Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat.

A few years down the road, we were in a flat, and in his room was my gran’s piano. And that was what we did. Schubert duets, Mozart, singing anything we could play, days of board games, evenings of bridge. Never a harsh word. Serendipitously, we were both contracted to the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC). Off to Stratford. We lived in converted stables seven miles out, and we made lifelong friends there, particularly Richard Griffiths, who also adored board games. Life was quite simply, idyllic. Ian and Griffo were rehearsing The Tempest. Ian was playing Ariel.

As a mild protest, he never took off his trenchcoat. “How’s it going, Griffo,’’ I asked. “Well, Ianov hasn’t taken off his coat yet. And Ariel is VHF.” Huh? “Very Heavy Fairy.” But Ariel has songs. And the RSC made a recording of it. (Find it if you can.)

The production was a mess. As they were watching the masque scene in which Juliet Stevenson and Ruby Wax were prancing about in black bin-bags, Ian and Alan Rickman told me that Michael Hordern (playing Prospero) would say “I’m so ashamed”, loud enough for the audience to hear. I picked Ian up after a performance and a student asked for his autograph (he always signed). She asked him if, when Ariel came on in this huge ruff, it signified he had transformed into a sea-nymph? He cried “Yes!’’ – delighted that she’d caught the designer’s intention. “Hmm,” she said, “well, you didn’t make it.”

We laughed all the way to the Dirty Duck, where Griffo was waiting. Another American student came up to our table: “Excuse me, Mr Griffiths, I just want to say you are an absolute genius.”

“Wot,” said Ian, “like Beethoven?” We laughed so much Griffo fell off his chair. And he was not an easy man to pick up off the floor. Ian started running in preparation for Chariots of Fire. Read the bible too. Cover to cover. “It’s all sex and violence.” The film made him rich. He took a share of the profits. But he remained unchanged. There was always an east coast Presbyterianism holding back any excess.

I say that, but after a celebratory lunch with Nigel Havers he clocked a drop-head Mercedes in a Park Lane showroom. “What do you think, Hilty?” “Go for it,” I said.

He was now in a ground floor flat in Hammersmith. I was in Barnes/Mortlake, so it was just a quick trip over the bridge for the resumption of games, piano and song. He had abandoned a film publicity tour of the United States – too much poking into his private life, desperately missing someone he had fallen for – and was resentful, I think understandably, that good film offers weren’t exactly pouring in.

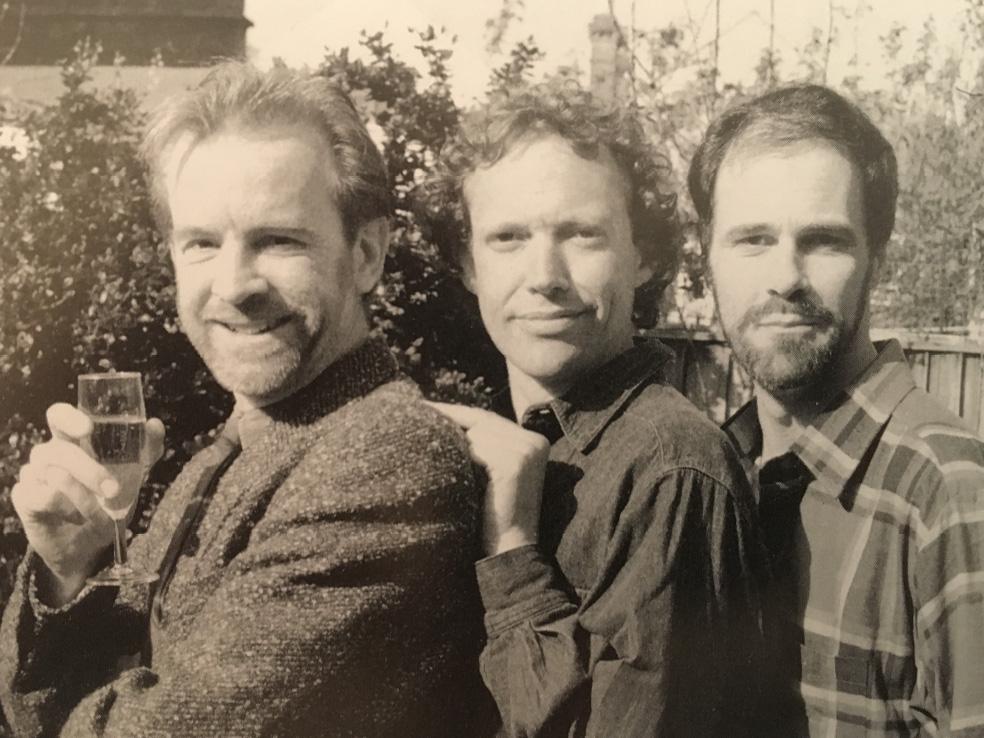

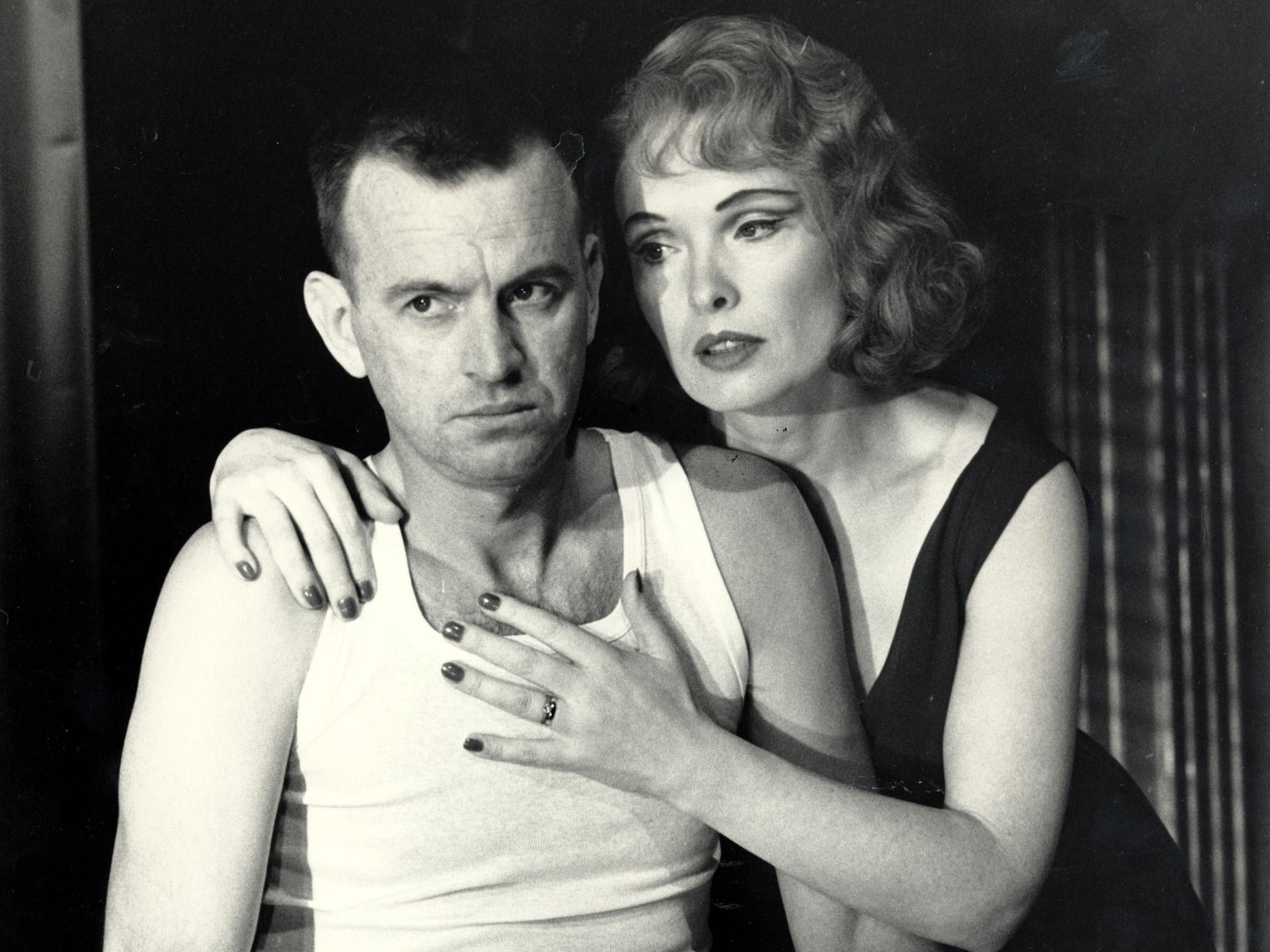

Work, circumstances, took me abroad. We drifted apart. Back in London there was an estrangement. But more than that: he had developed a shield around him which I couldn’t fathom. In Cat On A Hot Tin Roof he was a wonderful Brick. There was a serious weight and truth to his work, and a deep melancholy. We hardly talked that year and then in 1989 Ian came to our wedding party. Rintoul, too, of course.

I can’t remember exactly when but weeks later, maybe months, Rintoul called me to say he’d been working with Derek Jacobi and he had let slip that Ian was HIV positive. No, no. I couldn’t believe it. I went round to Ian’s flat with some fish and greens to cook for him, and we hugged. “You’re feeling my bones Hilt, aren’t you?”

I was just overjoyed to be back with him. And his story came out. He was diagnosed in 1986. New York bathhouse. Brazilian model. He was that specific. In Cat On A Hot Tin Roof he had asked Eric Porter not to push him so hard as he had bruised his chest. But it wasn’t bruising, it was the first Kaposi sarcoma. I went to see him doing a one-off gig of Martin Sherman’s Bent. The director, Sean Mathias, writes a lucid, heartfelt account in Ewen Maclachlan’s book Ian Charleson: A Tribute. Only he, costume and make-up knew he had now developed Aids. It was an unforgettable evening, with Ian receiving the loudest cheer at the curtain-call.

And then … Hamlet. Daniel Day-Lewis had left the production and Richard Eyre asked Ian to take over. He jumped at it, warning Richard that he had some sinus trouble. His body was covered in sarcomas, his eyes badly swollen. “All you’ll hear when I come on Hilt, is the rustle of programmes as the audience goes ‘Who the hell is this?’’ I didn’t see Hamlet, I was up in Dundee playing Macbeth, but we phoned each other. He eventually called a company meeting to tell the cast it was Aids. Michael Bryant (Polonius) went up to him afterwards and said: “I don’t care what you’ve got, you’re the bravest man I know.”

John Peter of The Sunday Times wrote a full-page review and, by the way, sent a magnum of champagne: ‘[The] masterful new Hamlet: Ian Charleson ... Technically he employs clarity combined with a powerful dramatic drive. His delivery is steely but delicate. The words move with sinuous elegance and crackle with fire. His Hamlet is virile and forceful ... He oozes intelligence from every pore ... The way Charleson can transform a production is a reminder that actors are alive and well, that directors can only draw a performance from those who have one in them and that in the last analysis the voice of drama speaks to us through actors.’

That naughty Ian McKellen said to me later: “Imagine being Dan Day-Lewis lying on a beach in the South of France and reading that!” I called Ian to congratulate him. He was so, so happy. He played Hamlet one more night. Ian McKellen was in the audience. The next day Ian McKellen won an Evening Standard Award, and in his speech said it should go to our Ian.

We learned, through the sculptor David Cregeen, that there was this healer in Bath who was seemingly having astonishing results with Aids sufferers via a form of light therapy. We would have done anything. Any straw. This was in that all too brief window before the relative effectiveness of AZT and the combination drugs.

Hugh Hudson, the director of Chariots, got us rooms in the Royal Crescent Hotel. Jonathan Pryce lent me his spacious comfortable Mercedes and I drove Ian and his Mum down there – for as long as the treatment might take. He had his first session with the lights man. Next morning Jean and I were having breakfast in my room when suddenly the double doors were thrown open. Ian sailed in, a huge smile, arms wide: “I feel wonderful!”

Later that day, my phone rang: my gran had died. Jesus, what are you to do? I had to go. Rintoul took over my post. And of course, the lights didn’t work. Rintoul and Patsy Pollock looked after him back in his Hammersmith flat, fielding callers, all sorts of friends, feeding him, and Patsy administering morphine. He had decided to end the chemo and everything else. Lindsay and I put in a few hours one day, and Ian got up. We laughed about his unfinished paintings – and he ordered a pile of paints and brushes – “It’s difficult being a Renaissance man.”

He talked of the joy of Hamlet, and that he was looking at Benedick – and Lear. Rintoul rang me on a Saturday morning, declaring Ian’s bad. The family is flying down. Will you pick them up from Heathrow? Of course. “How is he son?” asked his dad. “It’s not good Jack.” And a tear fell on his wee battered suitcase. Ian was in a coma, and died around 6 o’clock, Twelfth Night, 1990.

He didn’t talk of death. In fact there was a shyness, even a loneliness, a deep socialist understanding of respect for other men (and women), that he was no better than anybody else

Next morning we discussed what to tell the newspapers. Ken was clear. Septicemia. But too many people knew, I ventured. Only six weeks ago he had given a definitive Hamlet: a miracle of strength of body and mind racked by a bout of pneumonia, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, with that astonishing stubornness and absolute bravery born in a Scotsman. And Jean agreed. And so the front pages recorded “Chariots of Fire Star Dies of Aids”. Most of Jack’s Edinburgh golf club members never spoke to him again.

It states in Wikipedia that Ian “requested that it be announced after his death that he had died of Aids in order to publicise the condition’’. No, no. He was far too private. He didn’t talk of death. In fact there was a shyness, even a loneliness, a deep socialist understanding of respect for other men (and women), that he was no better than anybody else.

“You’re a real man, Hilt. I wish I was a real man.” He had said this years before, and it took me aback. Because it had never occurred to me that either of us would ever be defined by a term like that. Much as we had rejected our fathers’ entrenched views on man/woman, sexual politics, and much else, here he was expressing some sense of failure to meet the expectations of the time. It shocked me, because in all respects here was my best-ever friend, my teacher on how to live, how to be, how to care, how to laugh, how to share, how to dance.

“We defy augury ... there is special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, ’tis not to come. If it be not to come, it will be now. If it be not now, yet it will come – the readiness is all. Since no man of aught he leaves knows, what is ’t to leave betimes? Let be.”

He has left a legacy. The Aids ward at the Royal Free is named after him. Richard Eyre, John Peter and The Sunday Times established the Charleson Award, which goes to actors under 30 who excel in classical roles. It’s our favourite award ceremony. As a postscript, I wanted to list the Tory MPs who have consistently voted against gay rights and same-sex marriage. They’re the same guys who vote against the ban on hunting. But there’s just too many of them...

Nearly a million people still die from Aids each year. And Aids continues to disproportionately affect the gay and trans communities. For more information, please contact Frontline Aids, which has a special fund that supports the LGBT+ community https://frontlineaids.org

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments