How a stretch in Hydebank Wood can change your life

For many ex-cons it can feel like the punishment continues even when they’re out of prison. Andy Martin visits the ‘secure college’ changing all that

Keith is not your average ex-con. For one thing, at the tender age of 27 he’s made over a million in the last three years – legally. And I shouldn’t even call him an ex-con: he’s more of a graduate, having been a “student” as they call prisoners at Hydebank Wood College in Belfast. He’s doing a lot better than most graduates. Keith gives a lot of credit to Tommy O’Gorman, one of Ireland’s most successful businessmen, who sold Cove Energy a few years back for a cool couple of billion. This is the story of how Keith met Tommy – and how a spell in Hydebank Wood can change your life.

Keith was ultimately convicted for firearms offences, but the charges that put him away were serious enough to mark him out as a Category A prisoner – the most dangerous type of offender, and the only one in Hydebank Wood. He’s over six foot and well-built so his first day a heavy guy comes up to him and says: “I run this prison.” To which he replies: “I don’t want to run the prison, so we’re fine.” Eventually he was moved to a less secure wing and granted more freedom. He served two and half years inside, where he became the manager of “The Cabin”, the first café inside a prison that is run by the prisoners themselves.

When he got out he looked for a job. In order to get a job he had to get a bank account. He went to the bank to open an account, but as soon as he mentioned his recent stint inside, he was firmly shown the door. “All doors were closed to me,” he says. “You’re still being punished when you’re out.” So he decided to go into business for himself, just him and his laptop. Before his arrest, at the age of 19, he had completed the first year of a business degree at Dublin Business School and he had “done a lot of studying inside”. How hard could it be? He borrowed £1,000 from two friends and set himself up as a trader. He did his research, analysed the markets scrupulously, and invested all his money in Abercrombie and Fitch. It looked perfect. What could possibly go wrong?

“Within 15 seconds of the Wall Street market opening I was wiped out,” Keith recalls. The share price dropped by 10 per cent but since he had leveraged his initial capital by a factor of 10x it was all gone. To pay the money back he set about buying CCTV equipment on one side of the border and selling it on the other, exploiting a price discrepancy (or rather, since he had no money, he sold it first, then bought it, relying on Amazon Prime next day delivery). He made £70 per unit. Soon he had paid it all back and more. Then, in December 2016, he was introduced to Tommy O’Gorman.

“I spotted he was a genius,” says O’Gorman. “Keith was a clever guy to start with. I didn’t make him clever.” But he did loan him several thousand pounds to buy a VW Golf on a Monday. By the Wednesday Keith had sold it again at a profit of £2,000. After that he went back to the markets, following advice from O’Gorman, a man with the Midas touch. “It’s a learning experience every day with him,” says Keith. Now he is trading crypto and working on property deals and speculating in classic cars.

Keith points out that a lot of prisoners could make decent business people. “They’re mostly in there for buying and selling. Usually drugs. What they were doing is illegal, but it’s the same skill set. They have the entrepreneurial mindset. With the right intervention they don’t even need to be there.” Now he and O’Gorman are going back to Hydebank Wood – Keith’s alma mater – to mentor future entrepreneurs and try to set up a business school within the prison.

O’Gorman received a “Dear Tommy” letter from a young man saying that he would like to go to prison if only he could get mentored by Tommy. In Northern Ireland they trying to break in. No one has ever escaped from Hydebank Wood, perhaps because they aren’t really trying. This is not Shawshank or San Quentin or Sing Sing. There are lawns and tubs of flowers and hanging baskets and sheep grazing on the hill. It’s more like the grounds of an Oxbridge college, admittedly topped off with more rolls of barbed wire than commonly adorn the dreaming spires. I’m not sure instant millions are guaranteed, but I did drive up the leafy lane that winds towards the imposing front door of Hydebank Wood College (technically, “Secure College”), three miles outside Belfast City Centre.

They’re mostly in there for buying and selling. Usually drugs. What they were doing is illegal, but it’s the same skill set. They have the entrepreneurial mindset

The facade is instantly familiar, because it doubles as “HMP Blackthorn” in Line of Duty. Oaks from the original estate were felled to build the Titanic. This may be the first prison I’ve been in that could do with an image rights agent. I was given the grand tour by the governor, Richard Taylor, and his highly committed staff and I had the opportunity to speak to a number of the students. It was sometimes hard to tell staff and students apart, because they all wear casual clothes (admittedly Taylor himself wore a tie, which helped) and refer to one another by their first names.

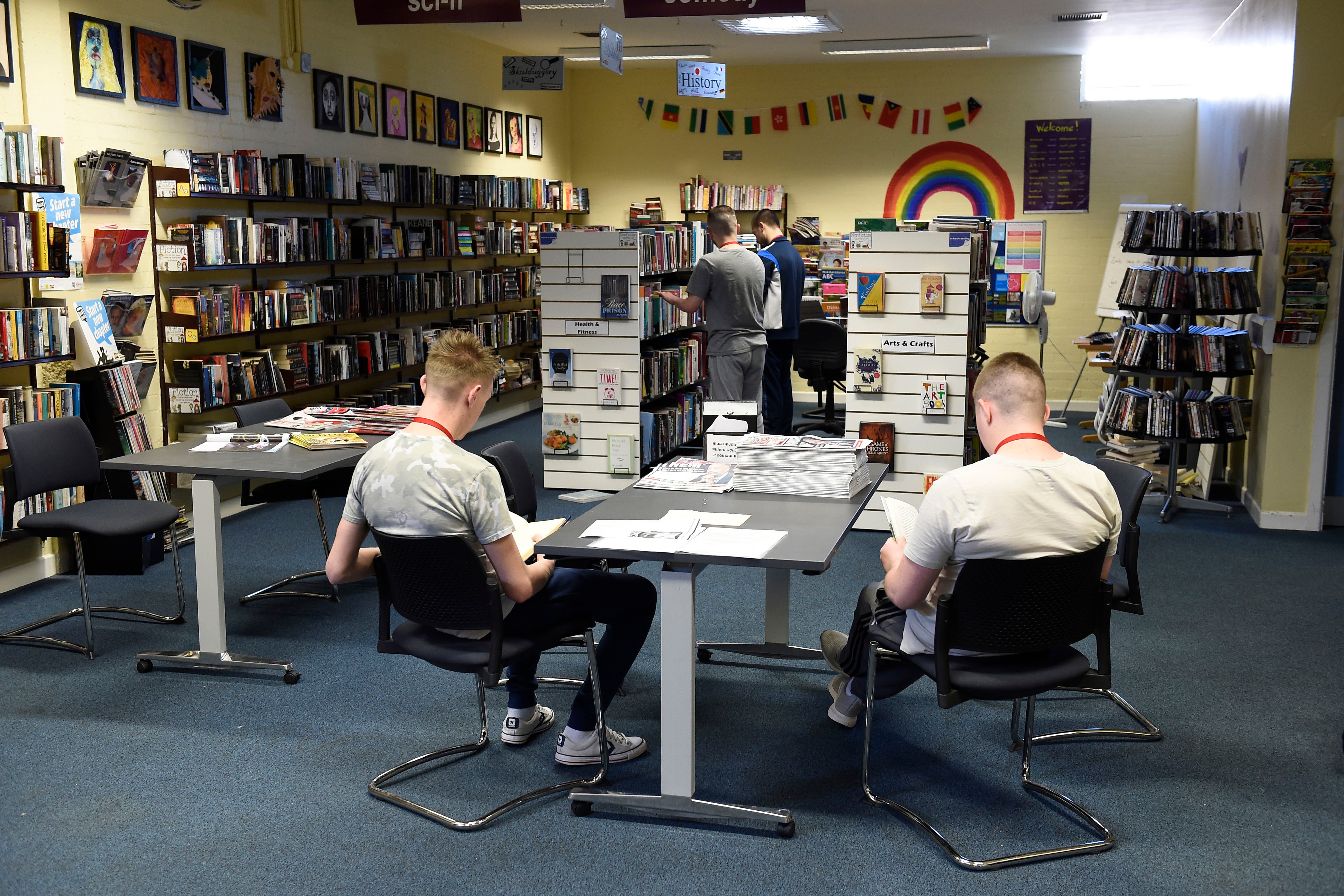

I got to hang out at the library and the recycling centre and the Personal Development Unit and to visit a residential block where they are replacing the old grills and bars with wood and toughened glass (so it is “desecuritised” and noise is reduced). I mucked about with Robbie the therapy dog, a big old brown Labrador. And I got to inspect the climbing wall at the superbly well-equipped gym. “So you’re training them up to climb the walls then,” I suggest to the physical education officer, Austin Willis. “Yes,” he says. “It’s all about keeping them out. It’s not a jail as you know jail.”

The new style jail-that-is-not-a-jail prioritises putting an end to re-offending. “The last victim has already been created,” says the governor. “We want to stop the creation of the next victim.” Taylor is a second-generation prison officer with over 30 years of experience who served for a while with his father at HMP Maghaberry. And he worked at the Maze during the Troubles. Taylor is a visionary who was drafted into Hydebank Wood in 2013 and given 18 months to turn it around after a disastrous report concluded it might have to be closed. Now it has become a beacon to other penal institutions, even – notably – in the United States.

Taylor was awarded a Rule of Law Fellowship that took him to Boston and a collaboration with Harvard. He met with an American counterpart, formerly a film producer and now elected “Sheriff” of the prison. He was telling him all about the benefits of pet therapy and the students’ work with goats and sheep and chickens and treating prisoners as individuals when the Sheriff interrupted him. “Our task is to keep the bastards in!”

But security is expensive. Then the Sheriff was hit with a budget cut of 20 per cent. Soon he was listening more carefully to talk of hens laying eggs and making election speeches saying that they needed to do things differently and put the emphasis on rehabilitation and pets. He sent staff over to Hydebank Wood to see how it was done and gives full credit for the transformation to Northern Ireland. Now his prisoners get their sentences cut by 50 per cent if they sign up to the programme.

“We call them students because it’s all about education,” says Taylor, who has an MSc and a diploma in conflict resolution from Coventry University’s Centre for Peace and Reconciliation. Hydebank Wood has several high flyers studying quantum physics and psychology and law in partnership with universities. Many others are doing GCSEs and A-levels and learning skills in the realm of plumbing, animal husbandry, hair and beauty, nutritional science and physical fitness. They have produced an award-winning graphic magazine about drugs in prison (“Craving the Blues”) and won the prize for “Top Ram” at the Balmoral Agricultural Show. A couple of the graduates of the system have gone on to work on Game of Thrones, filmed in Northern Ireland, one as a gardener, the other as a “food stylist”. But the harsh fact is that most convicts have suffered from a deficit of education in their upbringing. At Hydebank Wood no one talks of “illiterates”: they are “below entry level one”.

When one new arrival at Hydebank Wood was presented to him, Richard Taylor had to say to him, “I knew your father – and your grandfather.” Intergenerational crime is normal. But Hydebank Wood is aiming to break the cycle. The number of people re-offending after release from prison is lower in Northern Ireland than in the rest of the UK. The numbers of people locked up at Hydebank Wood has been cut by more than half. In a 2020 report the college scored 15 out of a maximum 16 points.

They are trying to fit back into society and society is rejecting them. You’ve got to give them something better than washing bottles in a pub. If you can take a young criminal off the streets and stop them committing crime, that’s got to be better for all of us

I had lunch with Karen, an iron woman, training up for a future triathlon, working out like mad in the gym. “I’ve lost a stone and a half since I’ve been in here,” she says. She is in her thirties with young kids that she hasn’t seen in a while – except over Skype – and she was chucked out of school early on with ADHD (for which she is now receiving medication). Karen is an engaging personality with a quirky sense of humour, she’s a fan of Love Island and Peaky Blinders and is on remand on a charge of murder. Her trial is up in November.

We were joined by Andy, serving a sentence of five years for GBH after stabbing someone at a party. He’s a specialist in sheep breeding while studying maths and English for an Open University access course and reading memoirs like Michael Maisey’s Young Offender: My Life From Armed Robber to Local Hero. And he has a young daughter. Prison, no matter how progressive, is always cruel.

There is a high percentage of young single parents in here. No one is locked up in their cells (they don’t say “cell”, they say “room”) 23 hours a day. No one is bored out of their minds and plotting their next heist. They can shop online at Sainbury’s and do their own cooking. Students on the autism spectrum get headphones to block out noise. But the reality is you’ve lost your liberty even if you do have a TV in your room. There are visiting DJs, but that hefty metal door is still slammed shut and locked at 7pm every night (unless you achieve “extra enhanced status” and obtain the key to your own room).

“The thing you have to understand about people in prison,” says former resident Keith, “is that they are people. They shouldn’t be demonised. There are a lot of good guys with talent in there.” The big idea behind the the business initiative is that you may not be able to find a job when you get out, but you can create a job for yourself and possibly others too.

O’Gorman is putting his hand in his own pocket to give graduates of Hydebank Wood the seed capital to start their own businesses. He is funding car washing machines, laptops, business cards. “You build up from there, it’s quite simple,” he says. “People don’t realise how easy it is to make money.”

And he is spreading the word. He put out a message on LinkedIn to fellow captains of industry, explaining what he was doing and seeking help. He got three thousand reads but only one solitary response from a wealthy hotelier willing to train up apprentices in hospitality. He is looking to inspire many more to pitch in and chip in funding. “They [ex-cons] are trying to fit back into society and society is rejecting them. You’ve got to give them something better than washing bottles in a pub. If you can take a young criminal off the streets and stop them committing crime, that’s got to be better for all of us.”

O’Gorman identifies with the students. He was born into hard times, forced to drop out of school at 14, was fired from a job as a trainee chef for burning the chicken, and found himself “unemployable” and “more or less homeless”. Latterly he has developed a habit of roaming about the graveyard in Newry and reflecting on the certainty of death. “Once you accept it, it changes the way you lead your life,” he says. “I often think that there’s not a single soul in there who – if they could – would not want to change their lives in some way. But I can, because I’m still here. So I’m doing it.”

O’Gorman’s confident can-do attitude reflects the spirit of Hydebank Wood. We’re still here. We can change if we want to. In the art and design facility, students have been painting large stones that will go to make a pathway through the gardens. One of them has painted a stone blue and inscribed it with the resonant self-referential message, “You rock”.

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Surf, Sweat and Tears: the Epic Life and Mysterious Death of Edward George William Omar Deerhurst’ (OR Books)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments