It is. Are you? The inside story of The Independent’s independence

David Lister was there months before The Independent printed its first ever copy. Thirty-five years later, he looks back at how its proud traditions and brand were established

I joined The Independent not at the launch, but two months before the launch. We had, after all, to prepare the thing, produce dummy editions, set up an entire structure. I was on the news desk, or an assistant home editor, as we were rather grandly titled. The reporters felt a little less grand when they rang people for stories and had to explain that no, The Independent wasn’t the local freesheet (many of which at the time were annoyingly called The Independent).

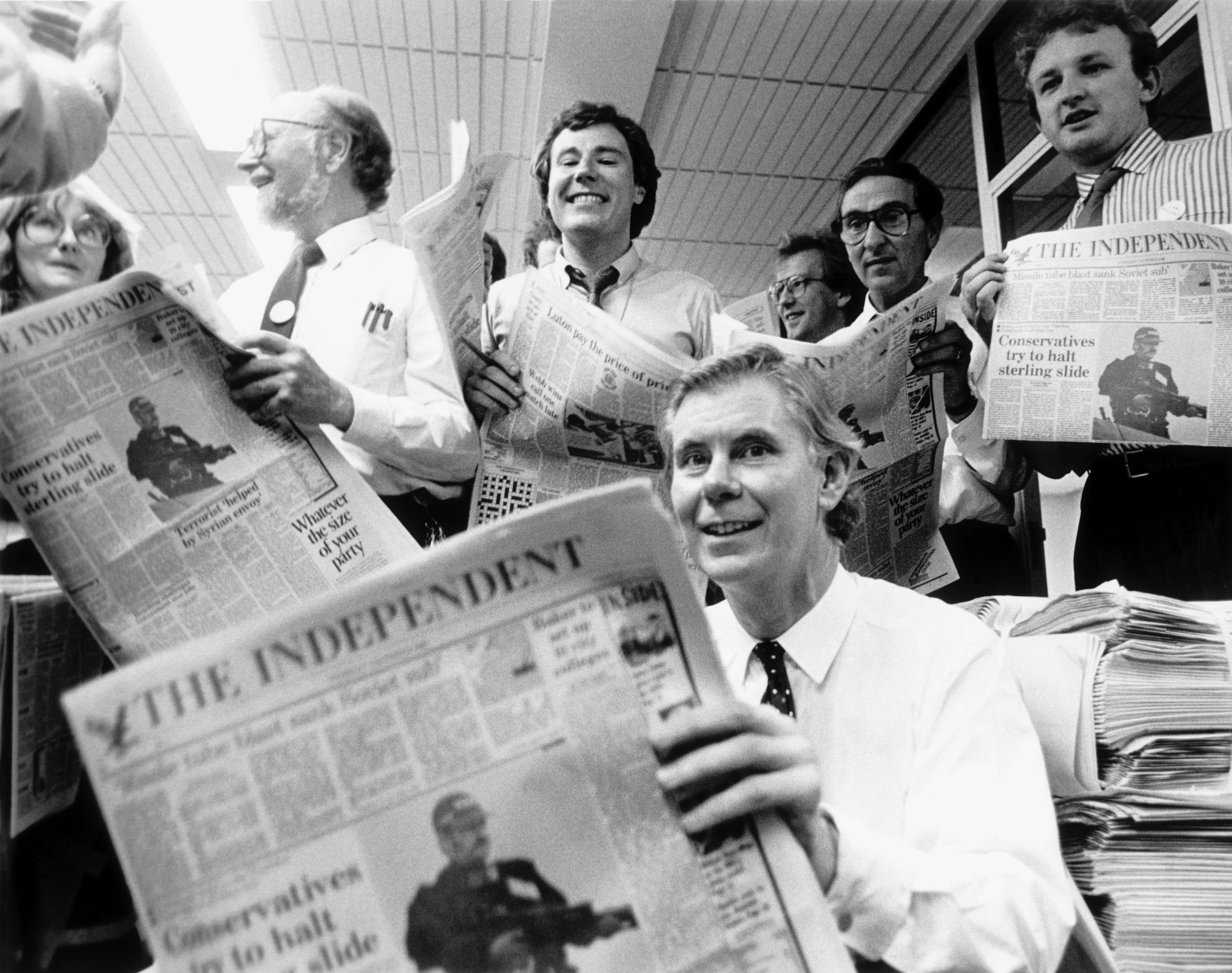

These were extremely heady days in City Road next to Bunhill Fields burial ground. Nothing in newspapers is as exciting as being in at the start of a venture. We were breaking new ground all the time. I and the other assistant home editors sat in the home editor’s garden one weekend discussing how we would treat the royal family. We also discussed how we would treat pictures, making them more dominant and agenda-setting than in other papers. The Independent’s photography became even more of a talking point than its treatment, and often lack of any treatment, of the royals.

Everywhere one looked there was innovation. We introduced arts listings, for example, now ubiquitous. We had a “no freebies” rule to underline our independence, although some staff members found ever more ingenious ways of getting round it. And we had weekly specialist pages for subjects like education, health and science – another innovation that was widely copied.

Arts coverage broke new ground with a daily book review and later a daily poem. Crucially they were not on the arts pages but on the op-ed pages in the central core of the paper. Books and poetry were an important part of every reader’s daily life, the message seemed to be. Certainly, that is what I took it to be.

The design, initially by Nicholas Thirkell but much perfected by Michael Crozier, won many would-be readers over: classic with a twist, as it was known, giving the impression that the paper had been there for years, and with an eagle perched on the top. I loved the eagle, but some of my colleagues were scathing about it. Indeed, in one of the early meetings when Andreas addressed the staff, he said laconically: “I am aware there is a ‘shoot that pigeon’ movement.”

On launch night there was a party and we queued up to have our first editions signed by Andreas Whittam Smith. Some things happened then, that one suspects could not happen now. The three founders, Whittam Smith, Matthew Symonds (father of Carrie) and Stephen Glover were all white, male Oxford graduates from The Daily Telegraph. Can’t quite see that happening now. And within a few days of the paper’s launch Andreas came across to the newsdesk and told us that we would be getting a 10 per cent pay rise as he admired how hard we were working. That too is no longer exactly a common occurrence. Shares in the fledgling paper were gifted to every employee too. I recall making a small profit on those a couple of years later.

I loved the eagle, but some of my colleagues were scathing about it. In one of the early meetings when Andreas addressed the staff, he said laconically: ‘I am aware there is a “shoot that pigeon” movement’

So much in those early years was done in maverick and unorthodox fashion. Symonds was a noted lover of fast cars. Indeed he was. When I had the temerity to ask to discuss my salary in the light of an offer from another paper, I went to see Matthew and it turned out we were going to the same Bruce Springsteen concert that night. He said he would give me a lift and we could discuss the pay situation en route. He drove at speeds which would make Lewis Hamilton’s eyes roll. By the time we arrived, I was so glad to be alive that I would have taken a pay cut. Looking back, his was a canny way of negotiating.

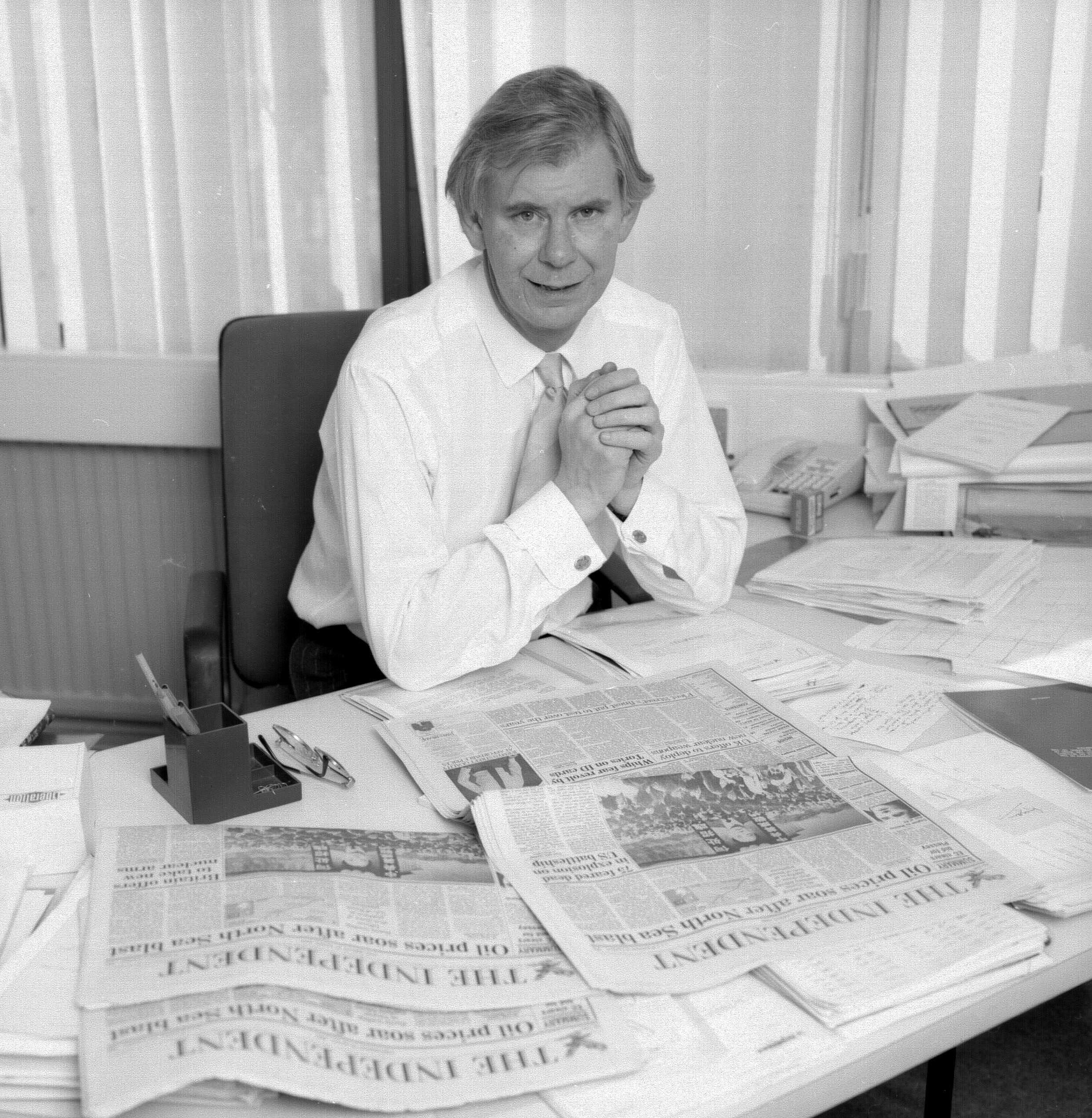

Andreas was inspiring and always approachable, which is not to say he could not be intimidating too. There was a fatwa against Salman Rushdie in February 1989, and the author had to go into hiding. I was arts correspondent by then and my byline was one of those on the story. Andreas walked over to me in full view of everyone, raised his arm and pointed at me and exclaimed: “I’m relying on you to find him!” A tall order even at a paper that broke all the rules.

And in those early days the paper was enormously popular. Despite the warnings of doom from pundits in Fleet Street (not to mention the worries of my parents!) readers loved it. The Telegraph, which had sent a wreath to us on launch day, (deposited by Andreas in Bunhill Fields near John Bunyan’s grave) had egg on its face. So sure was I of the success growing even larger that when the smashing guy who sat opposite me told me he was leaving to write books, I took him aside and gave him a stern lecture on how foolish it was to leave a triumph like The Independent to try your hand at books that were unlikely to make any waves. Fortunately, Bill Bryson ignored me.

In some ways The Independent was lucky. The Wapping dispute, when Rupert Murdoch sacked the printers and the journalists, including myself, had to work behind barbed wire, led to an exodus of experienced journalists from The Times and The Sunday Times to The Independent. There was a wealth of experience for the launch.

Readers loved it. The Telegraph, which had sent a wreath to us on launch day, (deposited by Andreas in Bunhill Fields near John Bunyan’s grave) had egg on its face

And in reaction to what was going on elsewhere in Fleet Street, Andreas championed the key vision of The Independent: balanced reporting, giving the writers their head and giving readers all points of view and trusting them to make up their minds and not be led.

The myth grew up that being independent meant being centrist, and later liberal or even politically correct. But left-wing columnists always jostled with right-wing columnists. Being Independent meant presenting both sides of the argument and trusting the readers to come to their own conclusions. A supreme example was the general election of 1987 in the year after launch. We did not even give a recommendation to readers on how to vote. We gave all sides of the political debate, and they made their own decisions.

Not every one of Andreas’s early wishes came to fruition. I recall him saying to me: “We won’t do anniversary journalism.” I don’t think that pledge lasted even until its first anniversary. He also said to a group of us executives that there was no need for sub-editors as good writers could be trusted to sub and cut their own copy. On that he had to be disabused.

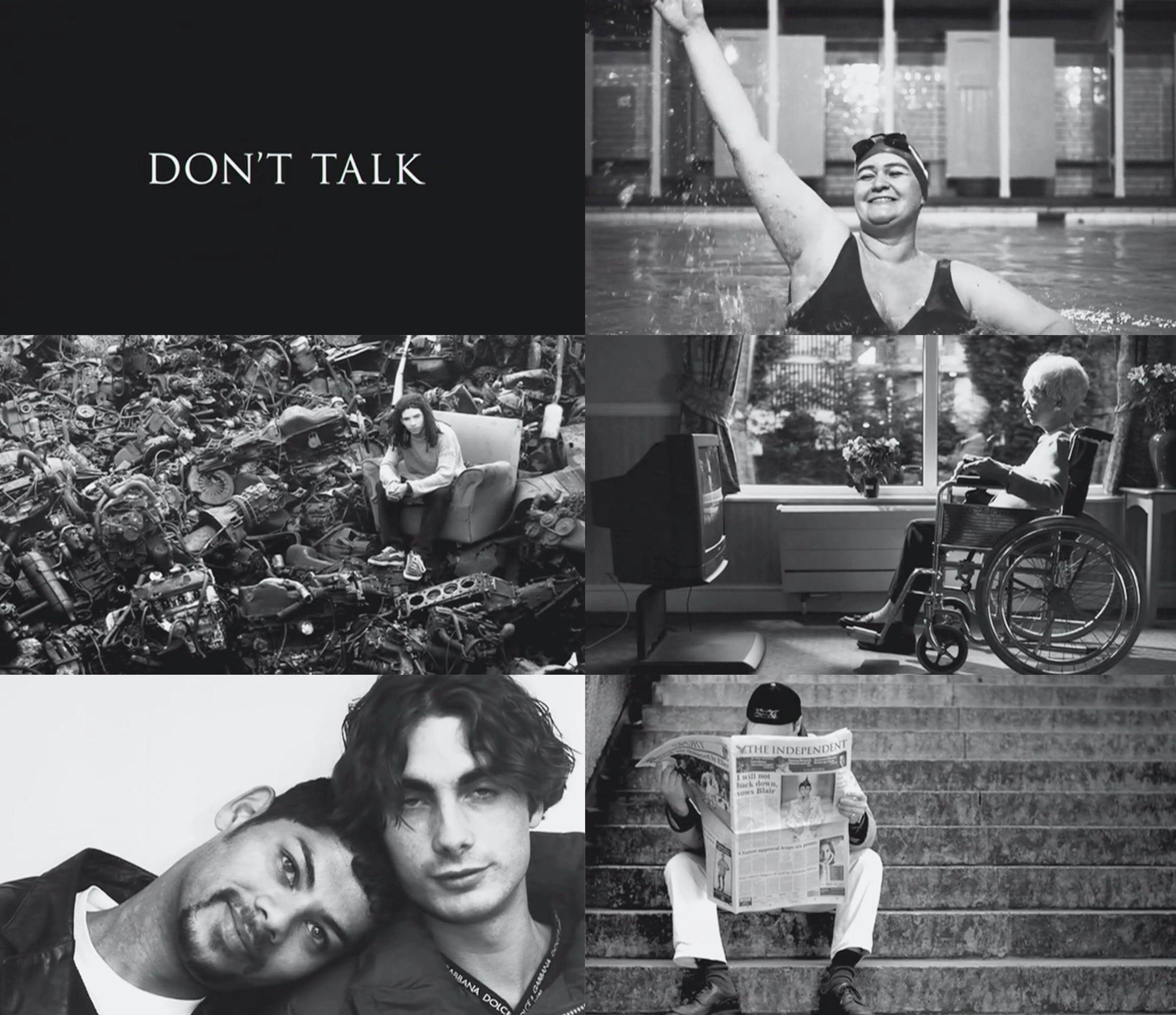

But the overarching concept of independence had to be sold. And here astute marketing had to be employed. The advertising agency Saatchi and Saatchi came up with the brilliant slogan “It Is. Are You?” We even had badges made, “I Am. Are You?”, for readers. The paper itself became a sort of badge one carried with pride, and the badges themselves drove home the message that readers belonged to a rather special club. We hadn’t expected that those badges would be worn by some members of the gay community and some gay activist movements, but they were, and we were delighted by that.

The “It Is. Are You?” concept was dreamed up by the creatives Paul Arden and Tim Mellors at Saatchi and Saatchi. It was all a bit cloak and dagger as Saatchi did major work for The Times and Sunday Times, who might not have appreciated their agency working for a rival. Meetings took place not in Saatchi’s plush offices, but in pubs, restaurants and temporary offices. Saatchi referred to the creative team working for The Independent as “the ghost squad”.

Mellors has recalled that Saatchi’s own research found the most popular name for the new paper was The Meridian. Thankfully, Andreas vetoed that.

The myth grew up that being independent meant being centrist... but being Independent meant presenting both sides of the argument and trusting the readers to come to their own conclusions

According to Mellors, “the name that researched the best was The Meridian, and I remember the glum faces in the room when the account man Robert Saville (later the founder of Mother), broke the bad news in the funny little office with its settees still wrapped in plastic, which Andreas had rented.

“The line ‘It is. Are You?’ arose out of a bit of body copy in a trade ad for The Meridian where the brief had been to talk about readers having an independent point of view,” Mellors recalled in an article in Creative Review. “So when Andreas finally got fed up with a name that he knew had researched well but that he personally hated and decided to call it The Independent, we did that agency trick and ‘repurposed’ an old line. The following day I had all the ads, posters and storyboards reworked with the new slogan so it looked like we’d meant it all along.”

The line benefitted from a touch of Saatchi surrealism from art directors Digby Atkinson and Chris Gregory. “We briefed Digby to produce posters of non-independent images, and we got Chris to make a film of sheep following each other into a butcher’s van. All very oblique but designed to appeal to the design-conscious, crossword-solving minds we pictured our readers possessing.”

Both slogan and newspaper had to be advertised on television, with the message of independence literally hit home.

Glover recalls in his deadpan style: “A young man is hit on the head repeatedly as we hear opinionated voices in the background. ‘In our opinion.’ Smack. ‘But in our opinion.’ Another smack. (Hang on. Isn’t this a bit violent?) And then a smooth reassuring voice tells us about a wonderful new newspaper which will escape the sins of the fallen world. ‘From October 7th. The Independent. It is. Are You?’”

First, though, with Meridian being kicked into touch, the name of the paper had to be chosen. The Chronicle and The Examiner were names that came up in market research. The Nation was also a name that had been flirted with, though Andreas quickly realised that it could have right-wing, even fascist, connotations. More than one person claims to have come up with The Independent, even the then cartoonist’s wife. Both Andreas and Matthew have claims, but its origins are somewhat shrouded in mystery. Research for Saatchi and Saatchi found that The Independent was seen as “a young name; quite left wing but not unbalanced; reasonably open-minded; no class bias; no bias to the professions or business; reasonable sex bias; good for both single and family people; very strong on modern outlook; low regional bias”.

Glover, with an inimitable but endearing pedantry that we would all experience from time to time in morning conference (woe betide the poor news editor reading out the list of stories who used the word refute wrongly), admits in his book Paper Dreams that his reaction was “pedantic”. “‘I’m a bit worried,’ I told Andreas, ‘that it’s not grammatical. It’s an adjective and I’m not sure that you can call a newspaper by an adjective.’ Andreas pondered this objection gloomily, then his face lit up. ‘I see what you mean,’ he said, ‘but what about Charles the Bold, where the adjective has the force of a noun? People would see the paper as the Independent one.’”

One of the rather special things about those early days was how editorial discussions could resemble debates in a university senior common room.

A key to success was that Andreas was always on the side of the reader, always concerned with what they would think. Often in those early days he would bring readers’ letters into morning conference and read them out. After all, they were the most immediate reactions to what they were doing. I have often thought how amazed readers then would have been if they had realised how much influence their breakfast musings had on the staff and direction of The Independent.

So often, it was to good effect. In concentrating on news stories, features, arts, business and the like we could forget what was also really important to readers. We knew they loved crosswords, of course. But it took a few readers’ letters to say that they would love to leave The Times for The Independent, but couldn’t do without the law reports. And so we quickly introduced daily law reports.

In time, of course, all our successful innovations were copied by our rivals. But a loyal readership stuck with us, and the name and its ethos were worth their weight in gold. I moved from the newsdesk to become arts correspondent, then arts editor and chief cultural commentator for many years, campaigning on issues such as cheaper theatre tickets and, most successfully, removing parked cars from cultural forecourts at Somerset House, the Royal Academy, the British Museum, so that those spaces could be enjoyed by the public.

Some of the values of those early days (published in a manifesto for the launch of the paper!) may have gone or been “amended” in the passage of time. The original broadsheet became a compact (we deliberately eschewed the word tabloid) and then, in 2016, the print edition was closed and The Independent became a digital offering with a large international readership. But it still campaigns, it still tries to offer an unbiased view on the world, and it is still possible to say: “It is. Are you?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments