Is Hermann Hesse’s philosophical fiction ready for a revival?

Today’s society is beset by similar existential crises that haunted the German-Swiss novelist, writes William Cook. So what can we learn from his literature?

In a sunlit courtyard in Montagnola, in the southern foothills of the Swiss Alps, German author and curator Regina Bucher is telling me about her lifelong fascination with Hermann Hesse. Regina moved to Montagnola in 1996, with her husband and their two young children. In 1997, she helped to establish the Hermann Hesse Museum, here in the hilltop village where Hesse spent the second half of his long life. In 1998, she became the museum’s director, and this year she retires. It feels like the closing scene from one of Hesse’s stories – a life come full circle, a search for spiritual enlightenment that ends back in the place where it began.

When I was a teenager, in the early 1980s, Hermann Hesse was everywhere. My parents read him avidly, and they weren’t the only ones. His novels sold over 150 million copies – not only in his native Germany and his adopted Switzerland, but all across the world. Translated into 60 languages, he was a familiar figure in Britain and America, popular as far afield as India and Japan. “He writes in a way that many people can understand,” says Bucher. “He really is a Weltburger, a citizen of the world.”

Hesse’s books weren’t just novels – they were more like religious parables. You didn’t merely read him for entertainment or escapism (though his best books provide a bit of both). You read him to learn about the meaning of life. He was revered by the hippies, for whom he became a guru. For anyone following the hippy trail, across Europe and on into Asia, Hesse was required reading. No hitchhiker’s rucksack was complete without a copy of his dreamlike tract, Siddhartha. The rock band Steppenwolf, who wrote “Born to Be Wild”, the soundtrack of the ultimate hippy road movie, Easy Rider, were named after another of his novels. “Before your LSD session, read Siddhartha and Steppenwolf,” advised Timothy Leary, the Acid advocate who coined the psychedelic catchphrase, “turn on, tune in, drop out.”

Regina Bucher grew up during the Cold War, in West Germany. “We didn’t read Hermann Hesse in school,” she tells me. “It was forbidden.” Undeterred, she read Hesse in her free time instead. In her 20s, in the 1980s, inspired by his idealistic writing, she went backpacking around India, the source of inspiration for so much of Hesse’s work. In the hostels where she stayed, even in the most remote parts of India, she often found copies of his novels. “He is an international writer, and he says a lot to young people of every culture,” she says. “Everyone can get something from his books.”

Yet by the time the Berlin Wall came tumbling down, in 1989, Hesse had virtually disappeared from British bookshops. Most of his books remained in print, but nobody apart from German specialists seemed to read him anymore. It was easy to see why. For the “Greed is Good” generation, the New Age ideas of the 1960s and 1970s were now terribly unfashionable, and for most folk Hesse’s transcendental odysseys were part of that dippy hippy package.

Like Bucher, I discovered Hesse in my teens, but for 30 years I forgot about him. But then, a few years ago, I spent a night in Lugano, a pretty lakeside town in Southern Switzerland, and learnt that Montagnola, the village where Hesse lived for 40 years, was only a few miles away. I made the short trip to Montagnola, paid a fleeting visit to the museum and found it fascinating, and resolved to return there as soon as possible for a proper look around.

And then along came Covid, and all our travel plans were thwarted. Finally, three years later, I’m back again – for a few days this time, rather than a brief overnight stay. I want to find out why Hesse came here, why he made his home here, why he wrote his greatest novels here. But above all, I want to answer a question that’s been nagging away at me ever since my first visit to Lugano: in today’s troubled times, beset by similar existential crises that haunted Hesse during his own lifetime, is his philosophical fiction now ripe for a revival?

Hesse’s life was framed by the First World War and the rise of Fascism; his posthumous fame was framed by the nuclear arms race and the Vietnam War. Today we’re facing a comparable set of problems: Covid, climate change, the war in eastern Europe... Hesse would have recognised our all-pervading pessimism, what the Germans call Weltschmerz. His stories address this sense of impending doom, the fear that humanity is hell-bent on self-destruction. These ethereal fables spoke to previous generations, in the 1920s and 1930s, and again in the 1960s and 1970s. Can they still speak to us today?

Hesse rejects the Christian notion that Christianity is the one true faith. Prophets of other faiths are accorded equal worth. Hesse’s work embraces God, yet it shuns organised religion

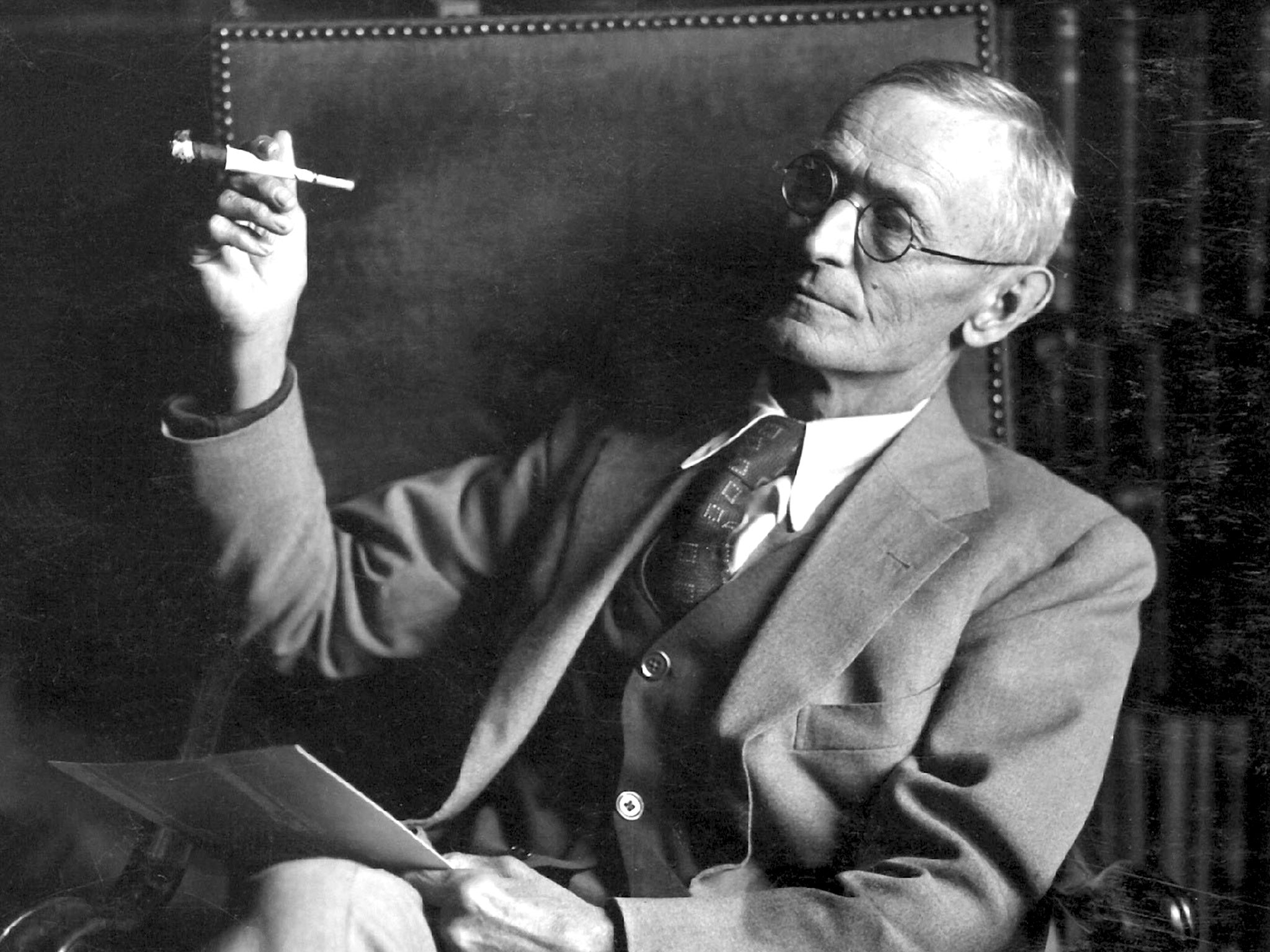

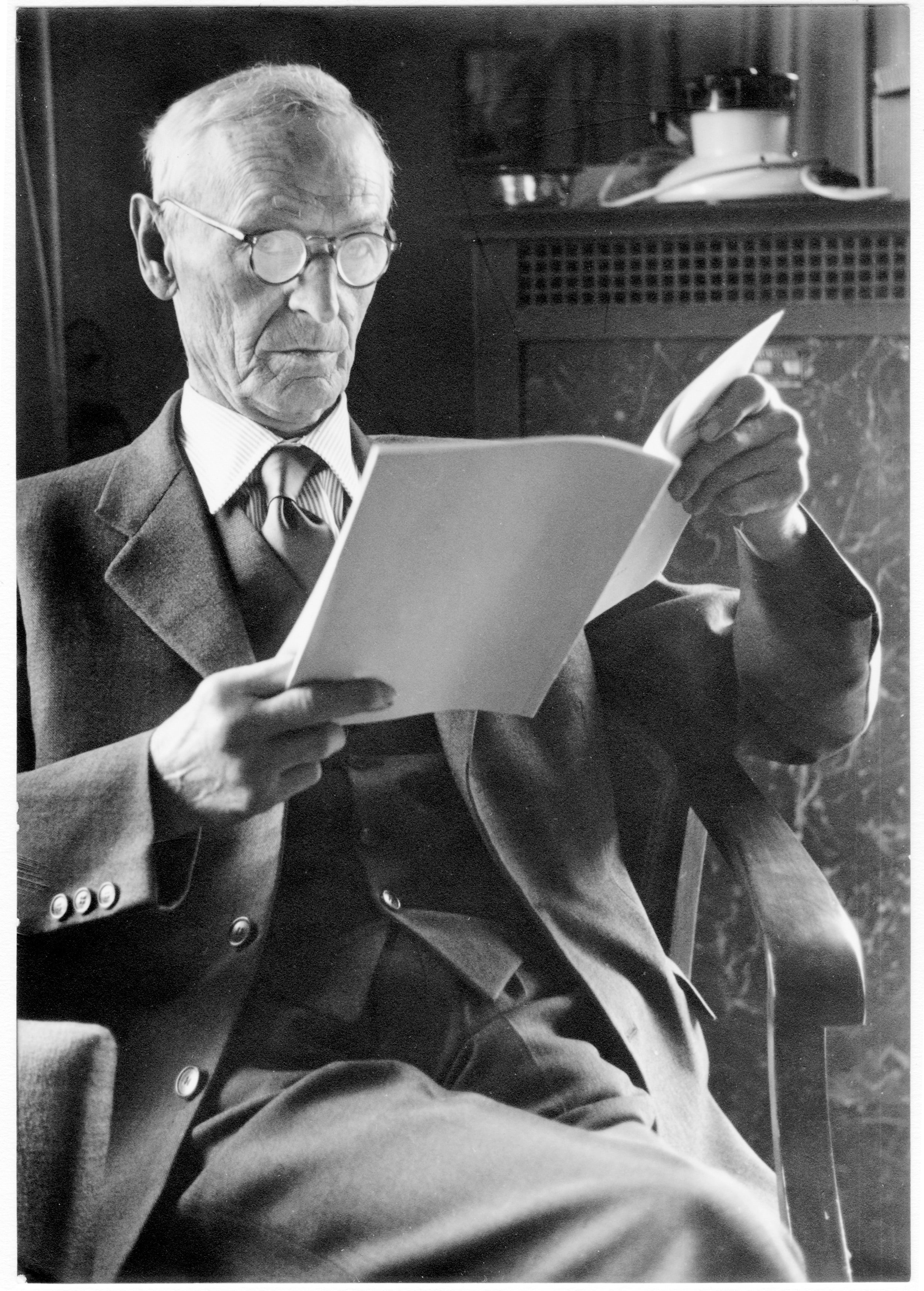

Hesse was a most unlikely hippy icon. He was born way back in 1877 and he died in 1962, before the hippy movement even started. He liked to live a quiet life. Like a lot of unconventional thinkers, he favoured conventional dress. Bookish and bespectacled, with a gaunt, ascetic countenance, he looked more like a reclusive academic than an outspoken champion of the counterculture. Yet there was something unusual and alluring about his unblinking gaze. If you looked into those penetrating eyes for long enough, you might have begun to wonder: had those eyes seen something the rest of us had never seen, a way of looking at the world anew?

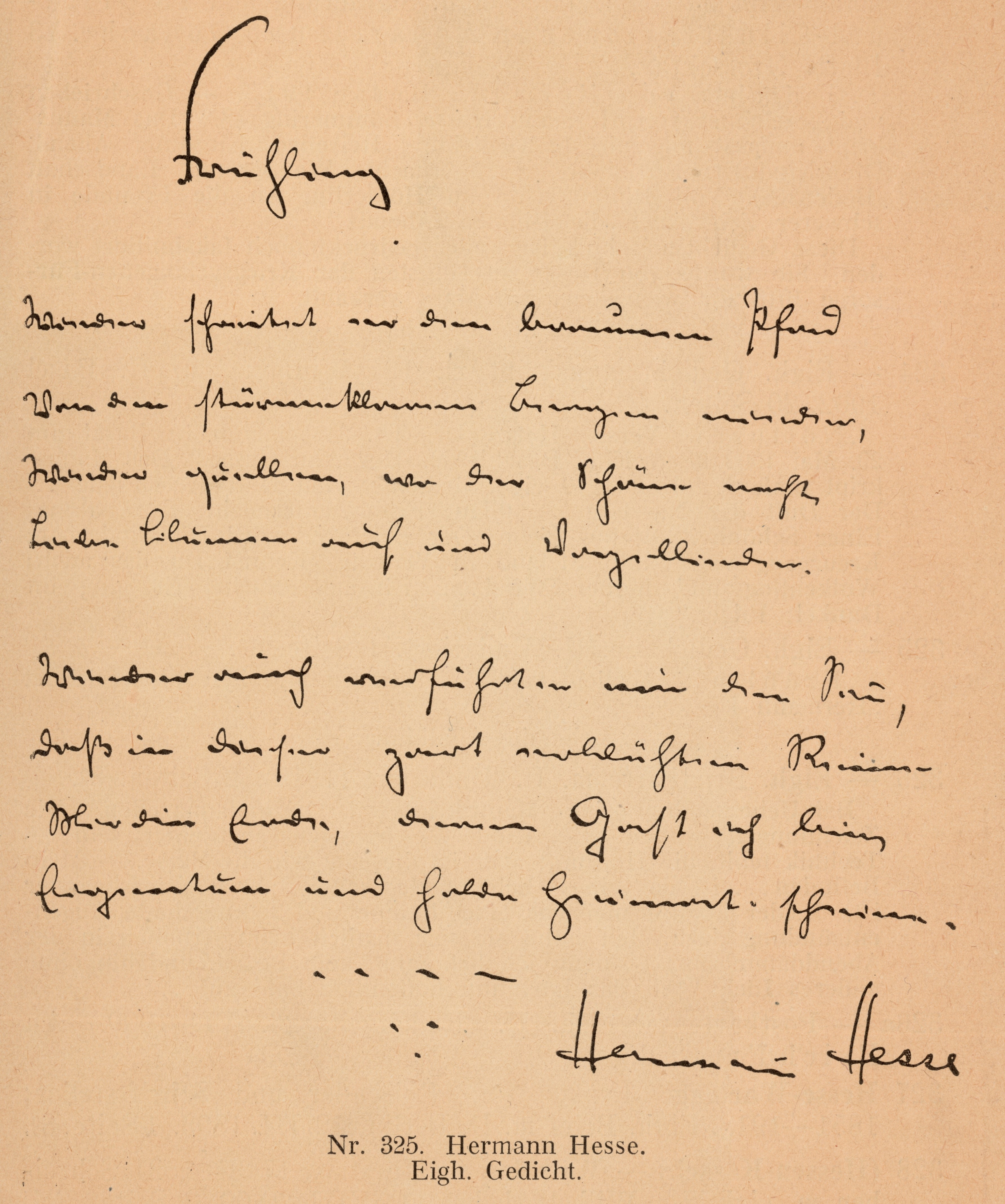

Hesse didn’t set out his ideas in a single manifesto. His philosophy is encoded in his writing – his novels, poems and short stories – and like all the best creative writing, it’s open to numerous interpretations. However, in virtually everything he wrote, one central idea cuts through: you need to find your own way through this life, even if it means refuting everything you’ve been taught to believe in: work, wealth, status, marriage, family, fidelity... Or, as Shakespeare put it: “Above all, to thine own self be true.”

This is Hesse’s first commandment, and everything he wrote stems from it, but it isn’t a license to do what you want without fear of repercussions or reprisals. In Hesse’s stories, every decision has a consequence, every action a reaction. The hippies were attracted by his espousal of alternative lifestyles, his contempt for bourgeois values, but despite his repudiation of conventional norms, his individualism was bound by its own morality. He anticipated Bob Dylan’s maxim: “To live outside the law, you must be honest.”

Many of his stories echo the teachings of Jesus Christ: love thy neighbour; judge not lest ye be judged etc. Yet Hesse rejects the Christian notion that Christianity is the one true faith. Prophets of other faiths are accorded equal worth. Hesse’s work embraces God, yet it shuns organised religion. His God is within us, and within the world around us. During his lifetime, it was his pacifism which marked him out as a radical. Rereading him today, the most radical thing about him is his reverence for nature. For him, the natural world is something to be nurtured, not exploited. In this respect, as in so many others, he was way ahead of his time.

He was born in Calw, a small town in southern Germany, into a pious Protestant family. When he was four, the family moved to Basel, Switzerland. His father ran a religious publishing house, his maternal grandparents had been missionaries in India – the tug of war between western and eastern attitudes remained a defining influence throughout his life. A clever, unruly child, he was sent to an elite boarding school, to be trained as a Lutheran minister, but he ran away, was expelled and committed (by his parents) to a lunatic asylum. Released after several months, he was apprenticed to a bookseller – a respectable trade, but a long way short of the profession his godfearing parents had mapped out for him.

Hesse published some poems in his early 20s, but his big breakthrough came in 1904, when he was 27, with the publication of his first novel, Peter Camenzind. A Bildungsroman (coming-of-age saga) about a young man searching for a raison d’etre in an unforgiving adult world, the format was familiar, but the style was something new. Hesse’s hero spoke with a modern voice, in a manner that was intensely intimate. “Other writers of his generation, like Bertolt Brecht and Thomas Mann, they are not so personal,” says Bucher. Hesse didn’t lecture you – he talked to you. The book’s success enabled him to quit his day job and write full time.

Over the next 10 years, Hesse cultivated a fairly conventional career as a fairly conventional novelist. His novels were sensitive studies of bourgeois life: unrequited love (Gertrude); the breakdown of a marriage (Rosshalde)... And then Germany went to war, and everything changed.

Hesse volunteered for the German army but was rejected, on account of his poor eyesight, and as the First World War went from bad to worse his writing was transformed. Before the war, he’d written about the real world, a world of security and certainty. Now, with dead bodies piling up in their hundreds of thousands, that old order was destroyed. Hesse responded by writing mythic tales, no longer rooted in the here and now. In Knulp, he created the archetypal drifter; in Strange News From Another Star he fashioned a series of futuristic fairy tales; in Demian, he created a sinister outsider with supernatural powers.

Hesse described Dostoyevsky as more of a prophet than a novelist. The same could be said of Hesse, and like all the greatest prophets, his lessons for living are refreshingly down-to-earth

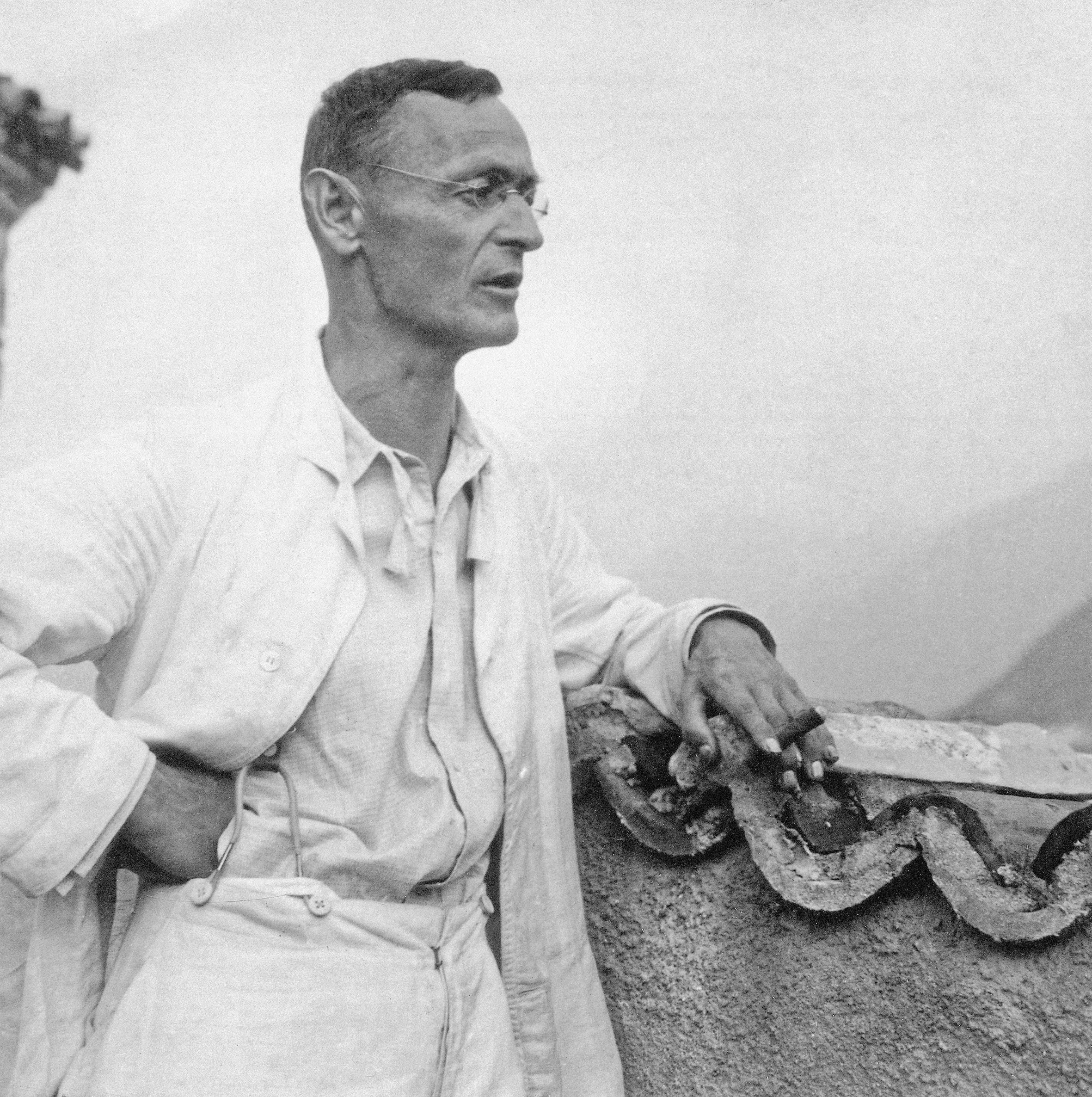

At the end of the First World War, Hesse reached a crossroads. German society had reacted angrily to the pacifist essays he’d written during the war, and now Germany was defeated and humiliated, this antagonism intensified. His first wife, who’d borne him three sons, had succumbed to schizophrenia. Hesse could take no more. In 1919 he left his family and travelled south, as far south as he could go without leaving Switzerland, to Montagnola, on the Italian border. Here he rented a few rooms in a crumbling old villa called Casa Camuzzi. It was here that he wrote the novels which secured his worldwide reputation.

Hesse’s first books in Montagnola were Klingsor’s Last Summer, a vivid novella about a painter, set in this Italianate landscape, and Wandering, an evocative collection of poems and short stories about his new homeland. “I am a nomad, not a farmer,” he wrote in an eloquent summary of the impetus for his migration. “I have wasted half my life trying to live his life. I wanted to be something I was not. I wanted to be a poet and a middle-class person at the same time.” This, he now realised, was impossible. “You can’t be a vagabond and an artist, and still be a solid citizen – you want to get drunk, so you have to accept the hangover.” Relocating to Montagnola, Hesse left his bourgeois life far behind. From now on, he lived entirely for his art.

Montagnola, and the surrounding region, Ticino, is a cultural and linguistic curio. It’s in the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland, surrounded on three sides by Italy – nearer Milan than Zurich, a historical no man’s land, seemingly neither truly Italian nor entirely Swiss. This suited Hesse just fine. Being in a place apart appealed to him: “When I see this blessed countryside again, at the southern foothills of the Alps, then I always feel as if I were coming home from banishment.” On this secluded hilltop, he could write in glorious isolation, yet Lugano was only a few miles away.

Today the Casa Camuzzi is a private residence, but the museum is in the house next door, right beside the building where Hesse wrote his greatest novels. In 1922 he wrote Siddhartha, an eternal, elemental tale of man’s search for spiritual fulfilment, which became a bible for the Woodstock generation. A novel of supreme simplicity, it could have been set in any time and place. However, his crowning glory was Narcissus and Goldmund, set in central Europe during the Middle Ages – it is perhaps the most readable of all his books, and also the most profound. Narcissus is a monk, a teacher in a monastic boarding school, and Goldmund is his brightest pupil. Narcissus is a man of letters, destined for a life of seclusion and contemplation; Goldmund is a man of action, destined for a life of travel and adventure. These were the two sides of Hesse’s personality – the two sides of all our personalities – and in this timeless tale, he created a perfect work of literature.

Narcissus and Goldmund was published in 1930 when Hesse was in his early 50s. He still had more than 30 years to live, but his best work was now behind him. As the Nazis came to power in his native Germany, he retreated from the wider world, devoting the next 12 years to his final novel, The Glass Bead Game. It’s the story of a monastic order devoted to the development of an aesthetic, cerebral game which synthesizes all the arts and sciences – the ultimate expression of human intellect and creativity. It was hailed as a masterpiece but I find it virtually unreadable.

Hesse watched the rise and fall of the Third Reich from the safety of neutral Switzerland. As a lifelong opponent of nationalism and militarism, National Socialism was a violent affront to everything he believed in, and though he was shielded from its worst effects, it was awful to see his Fatherland descend into murderous depravity, and drag the rest of Europe down with it, leaving Switzerland like a besieged island, surrounded by Fascist forces on all sides. He’d been a Swiss citizen since 1923 but Germany remained his Heimat. He had friends and family there.

In 1946, as Europe emerged from the rubble of the Second World War, and the true horror of the Holocaust became clear, Hesse was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. It wasn’t just a tribute to his writing. It also held out the hope that German, the language he’d always written in, a language traduced and tainted by Hitler and the Nazis, could become a language of beauty and humanity again.

When Hesse died, in 1962, at the grand old age of 85, Europe was in the depths of the Cold War, with no possible end in sight. “The present state of mankind springs from two mental disorders – the megalomania of technology and the megalomania of nationalism,” he wrote. I wonder what he’d make of the world today. Yet despite all the pain and suffering he’d seen, Hesse remained an optimist, and it’s this optimism that gives his writing its staying power. “Fate is not kind, life is capricious and terrible, and there is no good or reason in nature, but there is good and reason in us,” he said.

Hesse described Dostoyevsky as more of a prophet than a novelist. The same could be said of Hesse, and like all the greatest prophets, his lessons for living are refreshingly down-to-earth: know yourself, be yourself, follow your own path. You cannot change the world, but you can still strive to live your best life. “Almost all the prose works of fiction I have written are biographies of sorts,” he said. “These works of fiction are called novels. In fact, they are not novels at all.”

Towards the end of his life, Hesse was invited to review a new novel called The Catcher In The Rye by a debut novelist called JD Salinger. Hesse praised the book. “Poetry can achieve nothing higher,” he declared. He was far too modest to point out that he’d done something similar, even better, a generation earlier. In Demian and Steppenwolf, he’d created the first rebels without a cause.

After I’d looked around the museum in Montagnola, I sat outside beneath a big, old tree, and got talking to another visitor, a blind man who’d travelled here from Zurich. He’d grown up in Italy, just across the border from Montagnola, so this was a kind of homecoming, back to the place where he’d spent his childhood, back to a time when he could see. It turned out we were the same age, born one day apart. It felt like something Hesse had written. We said goodbye and he wished me Gute Heimreise (a good homecoming), and as I walked down the hill to visit Hesse’s grave, a simple stone in the local cemetery, I recalled my favourite Hesse mantra – so short and simple yet all-encompassing: “The world is beautiful, and life is brief.”

For more information about Hermann Hesse in Montagnola, visit hessemontagnola.ch, ticino.ch or myswitzerland.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments