How the Greens became a local election winning machine

The first Green Party councillor was elected in 1986, now there are 547 of them and they lead two councils. Colin Drury explains exactly how they managed it

It was shortly before midnight on 8 May 1986 when John Marjoram made British political history.

It was his daughter, Cleo, who broke the news to him. She ran across the counting hall of that year’s Stroud District Council elections. “Dad,” she shouted, “you’ve won by 44 votes.”

Thus, this one-time factory worker became the first Green Party councillor ever elected in the UK.

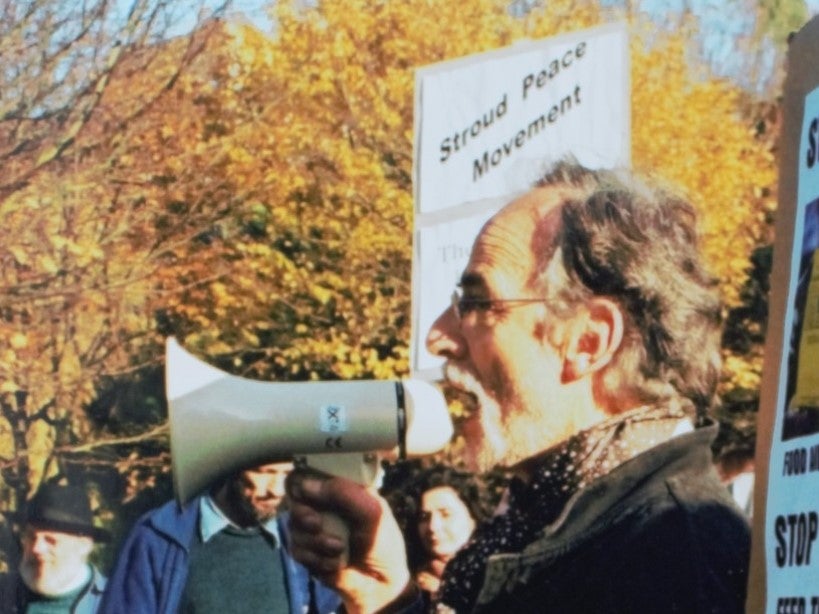

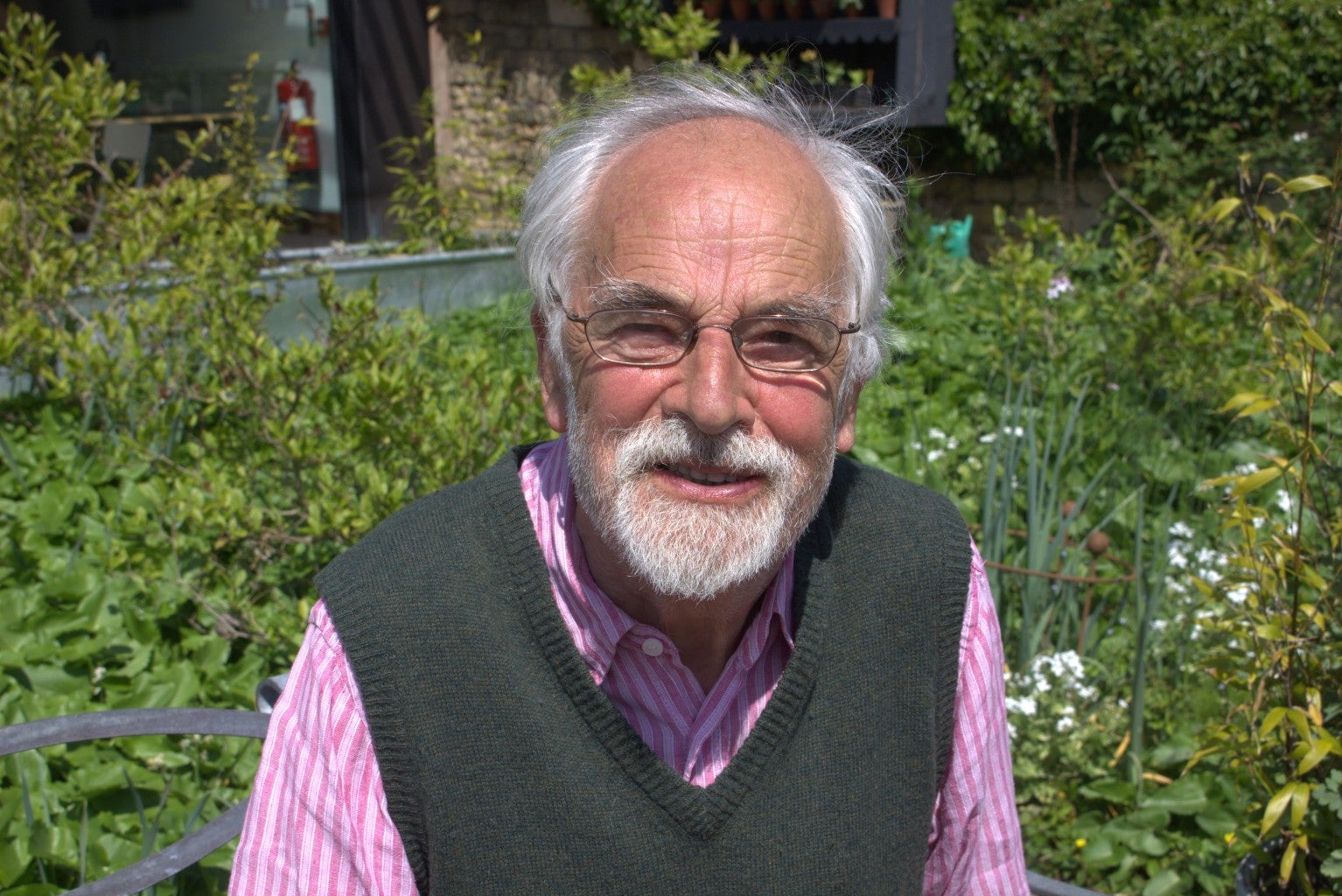

“It was an amazing feeling,” says Carol Kambites, co-founder of the Gloucestershire town’s Green Party along with Marjoram. “We never expected to win. Not that year anyway. It was the first time we’d stood. But a lot of people were already very fond of John. He’d spent years working in the community and people understood he cared about the same things as them.”

Marjoram himself – who would remain a councillor until 2021 – remembers being up all night after the result. “We were so high,” the 83-year-old says. “It felt like we’d done something unique.”

Thirty-six years on the situation is much changed.

At this month’s local elections, the Greens – led by Carla Denyer and Adrian Ramsay – won 124 council seats, taking their total to 547. While such a figure still means the party is a relatively minor concern – the Conservatives, by contrast, have more than 7,000 councillors – it shows an expansion of support that is growing all the time. Greens now sit all over, from Cumberland to Cornwall.

The party also currently leads two authorities – Brighton and Hove, and Lancaster – and is in a ruling coalition in another 13 including York and Worcester. They make up the official opposition in eight more including South Shields and Norwich.

Pertinently, there is an increasing confidence that this is just the beginning, that perhaps local election success will soon translate into triumphs in a general election. While the party still has just one MP – Caroline Lucas in Brighton Pavilion – bosses are convinced several more will join her by the end of the decade.

“There is now a pipeline of constituencies we would realistically be looking to win either next time or the time after that,” says Amelia Womack, the party’s deputy leader. “By 2030, I don’t think there’s any doubt we’ll see a Green group in parliament.”

It raises one big question. How did this party – only founded in 1972 and dismissed for years as well-meaning but fringe – become such an election winning machine?

Success did not come suddenly, or even consistently, after Marjoram’s 1986 breakthrough, it should be said. Progress for the Green Party remained slow for years – decades, even – after that.

As global warming has become more widely understood and ever more urgent, greater numbers of people have inevitably turned to the party which first warned about it

In 1993, when Marjoram himself founded the UK-wide Association of Green Councillors, the first meeting was so small it was held in his front room. Total numbers of elected members remained fewer than 40 until well into the new millennium. Even on Stroud District Council – a Green heartland of sorts – it wasn’t until 2012 that the party acquired power as a (junior) coalition member.

Real and lasting traction only came, perhaps, at the 2018 local elections when the party jumped from having 175 councillors to 362 in a single night. Plotted on a graph, the leap in numbers is so sharp, members today call it the “hockey stick” moment: the point at which a tiny upwards curve suddenly became near-vertical.

The obvious reason for this surge can, some suggest, be summed up in two words: climate change.

As global warming has become more widely understood and ever more urgent, greater numbers of people have inevitably turned to the party which first warned about it and which promises the most radical policies in tackling it.

On a sunny day campaigning with the Greens ahead of this year’s local elections in South Shields – where the party now has six councillors – The Independent heard this for itself. “The planet’s dying on its arse, man,” Paul Ahmed, a 62-year-old retired firefighter said as he promised his vote. “They were saying that before anyone.”

Yet it seems inadequate to suggest a shift in the zeitgeist alone explains the Green rise, especially when all major parties have now pivoted to prioritise climate change action – in word, if not always in deed. As Caroline Jackson, the Green leader of Lancaster City Council says: “Environmental concerns mean more people are willing to hear us out but the hardest work is then turning that into actual votes.”

As such, an equally important reason for the party’s growth over the last five years can perhaps be traced back to that historic victory in Stroud back in 1986. Wittingly or unwittingly, triumphant Greens have been following Marjoram’s templet ever since.

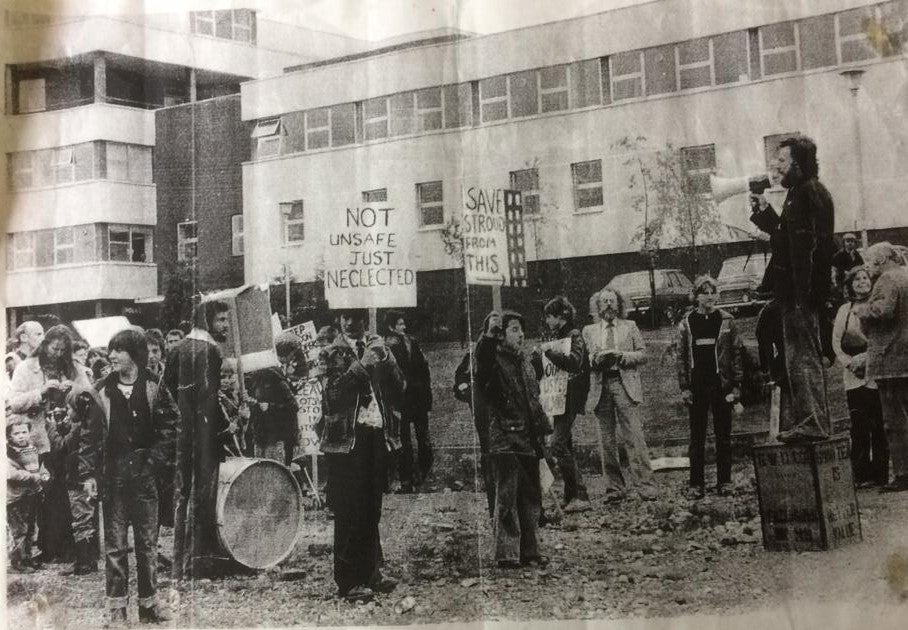

How so? Because his success came on the back not of a single campaign but of years of working in the community. Prior to 1986, he was already a well-known school governor, had run a local youth club and was instrumental in a campaign to save Stroud high street from being bulldozed. His lifelong opposition to nuclear weapons chimed in an election taking place just days after the Chernobyl disaster. Crucially, he was well-liked enough to be able to persuade a local Lib Dem candidate not to stand against him.

It meant that when he and his colleagues went out canvassing, says Kambites, they felt one step ahead of their rivals – because everyone already knew the candidate. “They didn’t necessarily know much about the party, but they knew John could be trusted.”

Fast-forward to 2022 and this is now a key part of the Green’s electoral playbook.

Potential candidates are told the surest way to secure a strong vote is to effectively behave like a councillor before becoming one. That is, to identify local concerns and get involved in campaigns to resolve problems; to engage with neighbourhood issues and stand up for the area.

The result of such action has been profound, says Chris Williams, the party’s Birmingham-based head of elections.

“It means that when we knock on doors at election time and say, ‘oh, I’m calling on behalf of David Jones, he’s your Green candidate’, before we even finish that sentence, people are already nodding along because they already know who David Jones is,” he says. “They already identify him as someone who cares for the area and gets things done. He has already won their vote in a lot of cases.”

Green success is littered with examples of this kind of graft.

Williams himself was one of a whole raft of party members elected to Solihull Council from 2008 onwards after the local party led opposition to a hugely unpopular regeneration project in the West Midlands town. In Sheffield, large electoral advances were made after party activists became prominent in the fight against the city’s now infamous tree massacre. Over in Lancaster, Jackson spent years as an anti-fracking protester before ever running for office.

“We are about doing politics with people rather than to people,” says Williams. “And we understand we don’t have to wait to become councillors to begin making a difference.”

That “shoe-leather” approach, party members say, contrasts with their Conservative and Labour counterparts who are increasingly perceived to be taking the electorate for granted, especially in so-called safe seats. Such as in Bradford.

“Labour didn’t have a challenger in some wards here for decades,” says Martin Love, the West Yorkshire city’s first Green lord mayor and one of six Green councillors. “Some of them thought all they had to do was wear a red rosette once a year and they’d be safe. So, when we came along knocking on doors, all year round, asking if people had issues – there was an element of disbelief that anyone cared.”

The party’s success in Europe, meanwhile, has added further to the sense it can be responsible in power and – a long-term voter doubt – that it can be trusted with the economy

Against this backdrop of discontent with the orthodox parties, the Greens have further enhanced their credibility by professionalising.

“I sometimes say the Green Party was set up by very well-meaning people who could see a vision for a better world and they knew they had it right,” Williams told The Independent previously. “But they didn’t always know how to explain that vision or how to make it relevant to people’s lives. So, over the last few years, this is something we’ve really focused on.”

Initiatives such as centralised training programmes for wannabe councillors and MPs and a future leaders scheme to identify young talent have been created. A dedicated staff field team now supports volunteers in running successful campaigns. Four-day bootcamps are regularly held to share best practice among members aiming to generate wider support. One stat is boasted about more than any other: pound for pound spent, the Greens claim to win more votes than any other political party.

“The idea is you create a winning mentality,” says Williams. “You get person X in, who has run a fantastic campaign, and you have them speak to other members about what they did in their area and how that can be applied to other areas. You workshop it all. You show that, once the Greens have council seats, we do great things – so the question becomes what’s the best way to get more of them?”

Everything from election literature to how members should approach doorstep conversations (“less talking, more listening”) has been overhauled in a bid to become a more efficient vote-winning machine.

Leaflets are a good example, says Williams. “We used to chuck these things out with great big chunks of dense text and no images, and then we’d wonder why people weren’t reading them. Because they’re busy and they didn’t have time to work through an academic essay.”

The answer? “From 2017, we were relentlessly saying to volunteers: use fewer words, less academic language, more graphs. You know, it’s about catching people’s attention between everything else they have going on.”

Staff numbers have increased as more donations have rolled in. Eight years ago, the party had a central office of just 12 people. Today, that number is 60. “Still tiny compared to other parties,” says Williams. “But it means we can move faster and further in getting to where we want to be.”

Not everyone, to be clear, has necessarily embraced the change.

Some in the party’s Green Left faction have voiced concerns that the professionalisation is symptomatic of a deeper shift away from the movement’s radical roots. They worry that the increasing willingness to enter power-sharing council coalitions is proof the party is embracing the status quo it professes to rail against. “Tories on bikes,” is how one former Brighton member labelled the city’s Green-led council after it tried to impose pay moderation on bin workers.

Yet Williams disputes the suggestion the party has moved away from the 1972 founding ideals of its predecessor, the People party.

“Our policies today are the same as they always have been,” he says. “We just realised we had to use more professional techniques to change how we were talking to people, to explain how we could make life better.”

He considers an analogy: “We haven’t changed what’s on our market stall, we’ve just changed how we shout about it.” What is on the market stall is clearly also a significant factor in winning votes.

Whereas the party were once considered a one-issue set-up, much work has been done over the last decade to create a broader policy base which keeps the environment at its heart while also appealing to voters on both the left and right of the political spectrum.

Successful campaigns in Conservative areas tend to emphasise the party’s objections to big infrastructure projects (it labelled HS2 an act of “ecocide”), while those in traditional Labour neighbourhoods generally focus on commitments to taxing the rich and a universal income. In rural areas, Greens calls for the protection of green space. In urban settings, rent control policies get given priority.

The party’s success in Europe, meanwhile, has added further to the sense it can be responsible in power and – a long-term voter doubt – that it can be trusted with the economy. If Greens can be part of successful administrations in Germany, Ireland and Austria, so the argument goes, why not here?

More pertinently, perhaps, the party sits above the sleaze of Westminster – Partygate, Beergate, Lobbygate – and makes much of presenting itself as an alternative to the traditional parties. No one thinks people join the Greens out of political ambition, believes Bradford’s Love.

“They see our members for what they are,” he says. “People who want to improve the place – and the world – they live in.”

That, indeed, is exactly what Marjoram was aiming for all those years ago in Stroud.

His win that night in 1986 kicked off a 35-year council career. He won re-election every time he stood until his retirement in 2021. Even now, he remains an active member of the Make Votes Matter campaign which argues for proportional representation (PR), a system that would instantly see the Greens win more seats in Westminster.

So, how does he feel looking back? Like the party has achieved a lot but that more still needs to be done.

“We are still facing a climate crisis,” he says. “We can’t rest until there is more action on that. The traditional grey parties, you hear all this talk that we have to consider the economy. What good is the economy without a planet to live on?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments