What would George Orwell make of it all today?

The word Orwellian has come to mean whatever people want it to mean – borrowed and bandied about by the left and right. John Rentoul reviews a new collection of unknown works that reveal the true Orwell

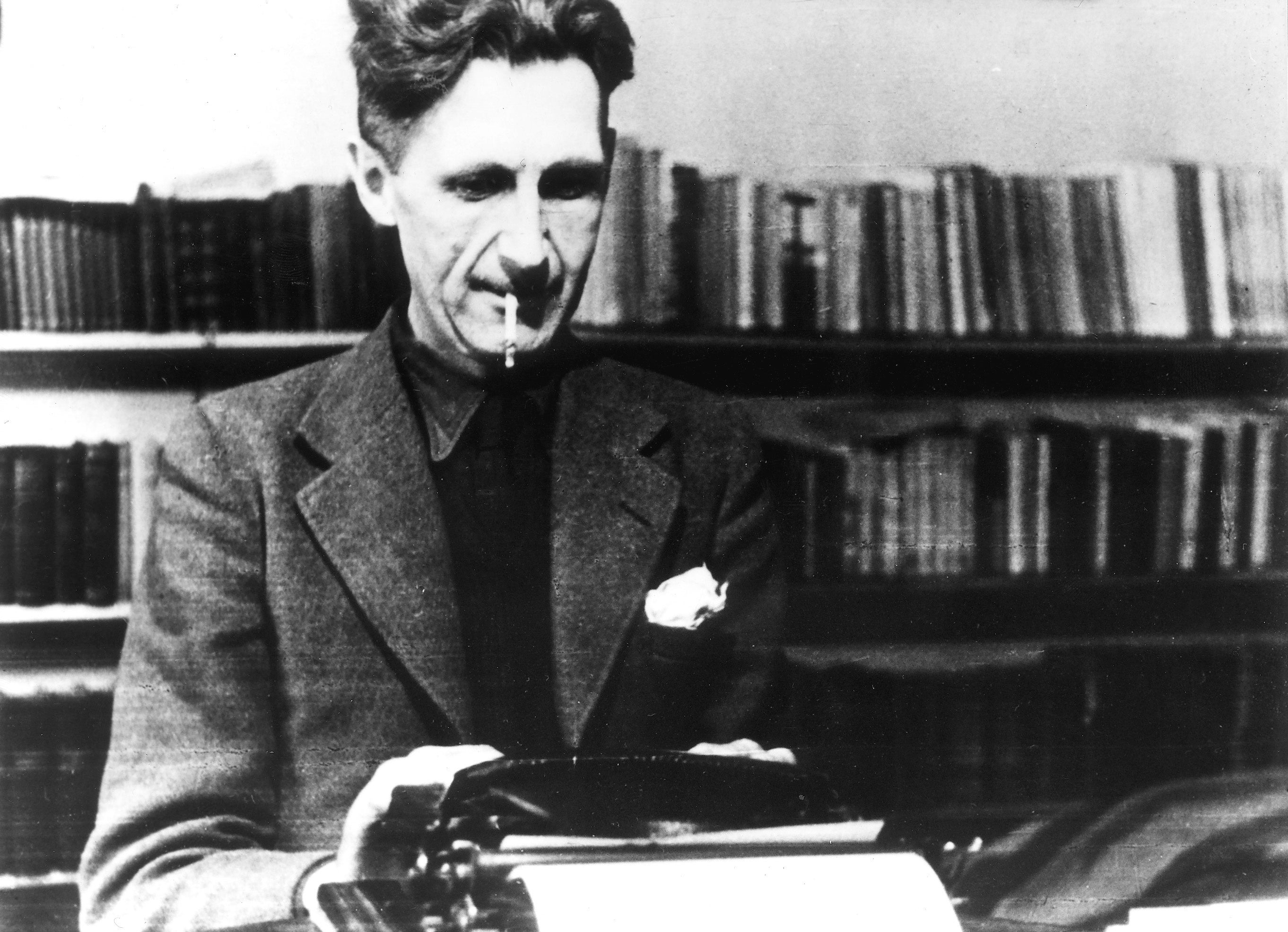

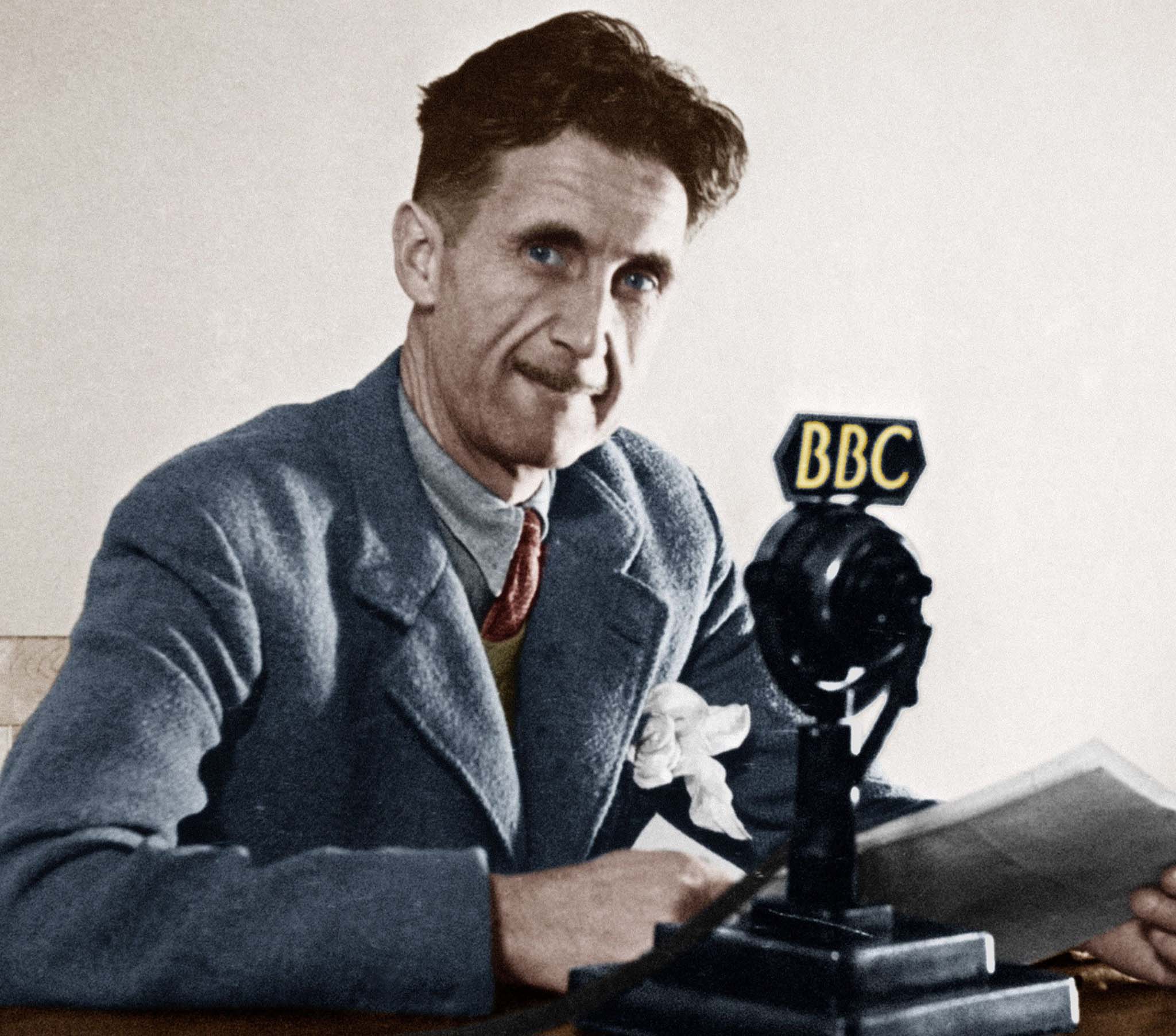

You can see why I have always admired George Orwell. His real name was Blair. He was of the left but suspicious of its extravagant and rhetorical forms. He was against totalitarianism of both left and right, but felt the betrayal of left-wing values more acutely, hence the emotional power of Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Obviously, therefore, he is a hero to those of us who thought New Labour was the best kind and that Eric Blair’s namesake was, on balance, a good prime minister. But Orwell was not a “centrist”, and I imagine he would have objected to the word. The use of words was another of his big things, and he might have had something to say about the propaganda uses of some of New Labour’s language. In fact, he did have something to say, in his 1946 essay, “Politics and the English Language”, about the word “progressive”, which was one of Tony Blair’s favourites. Orwell included it in a list of words used “in most cases more or less dishonestly”.

The way it has been taken up in just the last few years by the Bernie Sanders wing of the Democratic Party in the US makes Orwell’s point for him: it means whatever people want it to mean. “That is,” as he put it, “the person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to think he means something quite different.”

So, no, Orwell was not a centrist, or a progressive, because he would have wanted to stop forever to argue about what was meant by such terms, but he described himself as a “Socialist” (it usually had a capital S then) while being scornful of those who defended authoritarianism in the name of socialism. He was often claimed as “one of theirs” by Conservatives, his anti-communism appealing to the right during the cold war. But Clement Attlee was a resolute anti-communist.

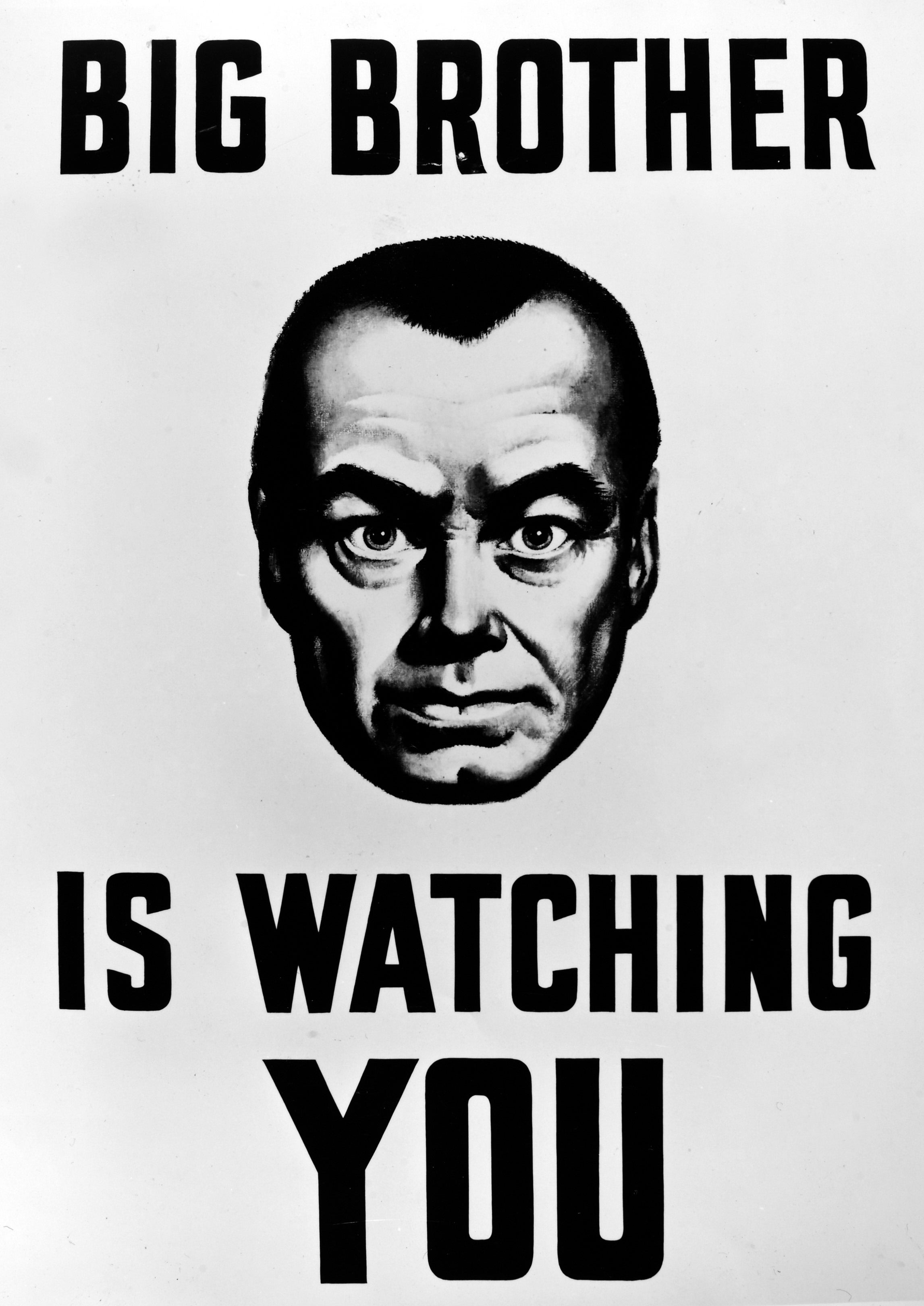

Orwell has been claimed, more recently, by libertarian Tories in their campaign against coronavirus restrictions. Before Christmas Desmond Swayne, the theatrical Conservative MP, looked up at the prime minister’s image on a screen in the House of Commons chamber and declared: “He loved Big Brother.” It is a tribute to the power of Orwell’s ideas that they are invoked by the other side, but that doesn’t make him one of theirs.

Anyone in search of the true Orwell should read a new collection of his “lesser-known short works” compiled by Cole Davis and published this month under the title Revenge is Sour. The title essay, from 1945, is a fine meditation about how, when someone to whom an injustice is done is in a position to take revenge, they no longer need to. That was no abstract philosophical question, but a practical one at the time about what to do about Germany and its defeated allies.

The book is an endlessly interesting collection for anyone who wants to go beyond the “well-known” Orwell, and indeed for anyone who wants to establish more securely whether he was one of ours or one of theirs. One of Davis’s criteria for including essays in the book, apart from “current relevance”, “rarity” and “excellence”, is that they show Orwell’s “development as a writer”.

Hence it starts with “Clink”, an odd article of first-person journalism in 1932, in which a toff pretends to be a penniless drunk in order to write about the criminal justice system: “I started out on a Saturday afternoon with four or five shillings, and went out to the Mile End Road, because my plan was to get drunk and incapable, and I thought they would be less lenient towards drunkards in the East End.” It followed a fashion at the time for slumming it for the purposes of social observation, and was a failure, in that Orwell seems to have expected it to have led to a searing exposure of the way the underclass is treated. Instead, it turned out that the police and court officials were generally quite benign, and the reader begins to wonder at the ethics of Orwell making such a nuisance of himself.

The article remained unpublished in his lifetime but, undaunted, Orwell learned from it and achieved some success with his first book, on a similar theme, Down and Out in Paris and London, published the following year. “Clink” shows a determination to take on difficult subjects and an honesty about Orwell’s feelings that appears again and again in this collection, although it is curiously un-political, despite its obvious motivation of understanding poverty in order to do something about it.

As Orwell himself put it in a later essay in this collection, his preface to the Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm: “Up to 1930 I did not on the whole look upon myself as a socialist. In fact I had as yet no clearly defined political views. I became pro-socialist more out of disgust with the way the poorer section of the industrial workers were oppressed and neglected than out of any theoretical admiration for a planned society.”

Davis’s introduction is excellent in briefly tracing the development of Orwell’s political thought: it was the Spanish Civil War that gave him clarity. “Although as usual he was interested in picking up literary material, he genuinely wanted to join in the struggle against Franco’s forces and was apparently a fearless soldier,” Davis writes. Orwell was “cavalier with his wellbeing”, getting himself shot in the neck by a sniper: “He had literally stuck his head above the parapet.”

Not only did the war turn him away from his early pacifism: the repression by Stalinist forces of their former allies in the anti-Franco movement was to lead Orwell “on the path to his almost ceaseless literary vendetta with totalitarianism”.

In “My Country Right or Left”, in the autumn of 1940, he seemed surprisingly diffident about taking up arms against Nazism: “If I had to defend my reasons for supporting the war, I believe I could do so. There is no real alternative between resisting Hitler and surrendering to him, and from a socialist point of view I should say that it is better to resist.”

As so often, there are parallels between Orwell’s writing and the controversies of today. He admitted that he was “patriotic at heart” despite his distaste for nationalism. “Patriotism has nothing to do with conservatism,” he wrote, so that he could be “loyal both to Chamberlain’s England and to the England of tomorrow”. Labour’s present confusions over the flag are not new.

His vision of the England of tomorrow, however, was not exactly a New Labour one: “Only revolution can save England, that has been obvious for years, but now the revolution has started, and it may proceed quite quickly if only we can keep Hitler out. Within two years, maybe a year, if only we can hang on, we shall see changes that will surprise the idiots who have not foresight. I dare say the London gutters will have to run with blood. All right, let them, if it is necessary. But when the red militias are billeted in the Ritz I shall still feel that the England I was taught to love so long ago for such different reasons is somehow persisting.”

The essay relates how he grew up in “an atmosphere tinged with militarism” and still felt “a faint feeling of sacrilege” if he failed to stand to attention during the national anthem: “That is childish, of course, but I would sooner have had that kind of upbringing than be like the left-wing intellectuals who are so ‘enlightened’ that they cannot understand the most ordinary emotions.”

Only revolution can save England ... I dare say the London gutters will have to run with blood. All right, let them, if it is necessary

How strange that Orwell could go in a few sentences from accepting that the London gutters will have to run with blood for the sake of a revolution to sneering at left-wingers who are out of touch with “ordinary emotions” – when he must have known what most people’s “ordinary emotions” would have been about a bloody insurrection.

Many of the essays in this collection tackle uncomfortable subjects. There is a book review of Mein Kampf, also written in 1940. As Davis comments: “Not unusually for him, Orwell is happy to take an unorthodox stance in the most unpromising of situations.” Orwell doesn’t waste much time on the book itself, but uses it to discuss why there is “something deeply appealing” about Hitler himself.

“One feels, as with Napoleon, that he is fighting against destiny, that he can’t win, and yet that he somehow deserves to. The attraction of such a pose is of course enormous; half the films that one sees turn upon some such theme.” What is typical of Orwell is that, by trying to understand the attraction of Hitler to the German people, he risks mockery by using his personal feelings to explore the subject.

He does the same in an essay on antisemitism in Britain, written early in 1945, just before the end of the war. He examines why he is “not immune to that kind of emotion”, as a way by which “one might get some clues that would lead to its psychological roots”. He writes: “I defy any modern intellectual to look closely and honestly into his own mind without coming upon nationalistic loyalties and hatreds of one kind or another … that antisemitism will be definitively cured, without curing the larger disease of nationalism, I do not believe.”

Again, there is a startling similarity between the controversies of three-quarters of a century ago and those of today. Today, Orwell would have provoked a Twitter storm; then he got letters when he wrote about antisemitism: “Whenever I have touched on this subject in a newspaper article, I have always had a considerable ‘come-back’, and invariably some of the letters are from well-balanced, middling people – doctors, for example – with no apparent economic grievance.”

I defy any modern intellectual to look into his own mind without coming upon nationalistic loyalties and hatreds … antisemitism will only be cured by curing the larger disease of nationalism

Then there was the cancel culture of the immediate postwar period, prompting Orwell to write a defence of PG Wodehouse, who – after the Germans had captured him in France, where he was living – had outraged British opinion by doing “non-political” radio broadcasts from Berlin in 1941. Orwell had little patience with the claim made in “several letters to the press” that “fascist tendencies” could be detected in Wodehouse’s books.

He wrote: “The events of 1941 do not convict Wodehouse of anything worse than stupidity. The really interesting question is how and why he could be so stupid.” Orwell’s explanation is that his success and living abroad “allowed him to remain mentally in the Edwardian age”, meaning that he was naive about the nature of Nazism.

Orwell concluded that the calls for Wodehouse to be tried for treason were a form of displacement activity: “In the desperate circumstances of the time, it was excusable to be angry at what Wodehouse did, but to go on denouncing him three or four years later – and more, to let an impression remain that he acted with conscious treachery – is not excusable. Few things in this war have been more morally disgusting than the present hunt after traitors ... In England the fiercest tirades against Quislings are uttered by Conservatives who were practising appeasement in 1938 and Communists who were advocating it in 1940.”

The sympathy for Wodehouse is what we might expect from Orwell, a socialist who despised most socialists, and who was intensely English even if, like Wodehouse, he observed the actual English as if from the outside.

This is a collection that is wonderfully varied, which captures Orwell’s distinctive smoky voice as it grows in confidence, and which offers some unexpected insights into modern controversies, such as those over antisemitism, authoritarianism and public morality.

But I was brought up short, in the preface to the Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm which I quoted earlier, by the sudden surfacing of Orwell’s personal life, as opposed to his interior life of feelings. Written in 1947, the preface is the best short summary of Orwell’s politics in his own words. He explains his disillusion with the Soviet regime in the USSR, and his frustration with western socialists who refused to see the regime for what it really was, which was his motive for writing the allegory.

At the end of the preface, though, the driving force of his argument and explanation stops suddenly and he writes: “I don’t know what more I need to add. If anyone is interested in personal details, I should add that I am a widower with a son almost three years old, that by profession I am a writer, and that since the beginning of the war I have worked mainly as a journalist.”

We are reminded how precarious Orwell’s life and work was. Animal Farm, which made him famous, was published in 1945, five months after the death of Eileen, his first wife, with whom he had just adopted a son, Richard. Nineteen Eighty-Four, which made him even more famous, was published in 1949, just before his death in 1950 at the age of 46.

This collection is a good guide to the range of his short life’s output. If there is a thread running through it, it is, as Cole Davis, the editor, comments, Orwell’s “search for moral and even emotional truths rather than political sophistication”. It was this insistence on clarity that gave Orwell’s writing its power. It was his clarity of thought, as well as his clarity of language, that made him so fierce in defending the values of democracy and equality against those who claimed to be on the left.

That is why he is so influential today. It is not just because he was the original Blairite that I admire him. It was his recklessness in taking on mushy, wishful, obscurantist thinking that made him so valuable, and that makes this collection so worth reading today.

‘Revenge is Sour: Lesser-Known Short Works’, George Orwell, edited and with an introduction by Cole Davis, published this month by Volitor, £13.85 paperback

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments