‘A masterpiece in its own right’: How the quietest Beatle finally found his voice

Fifty years after George Harrison’s first solo album following the break-up of the Beatles, Sean Smith looks back at how McCartney and Lennon’s ‘kid brother’ broke free and found what he craved most: vindication

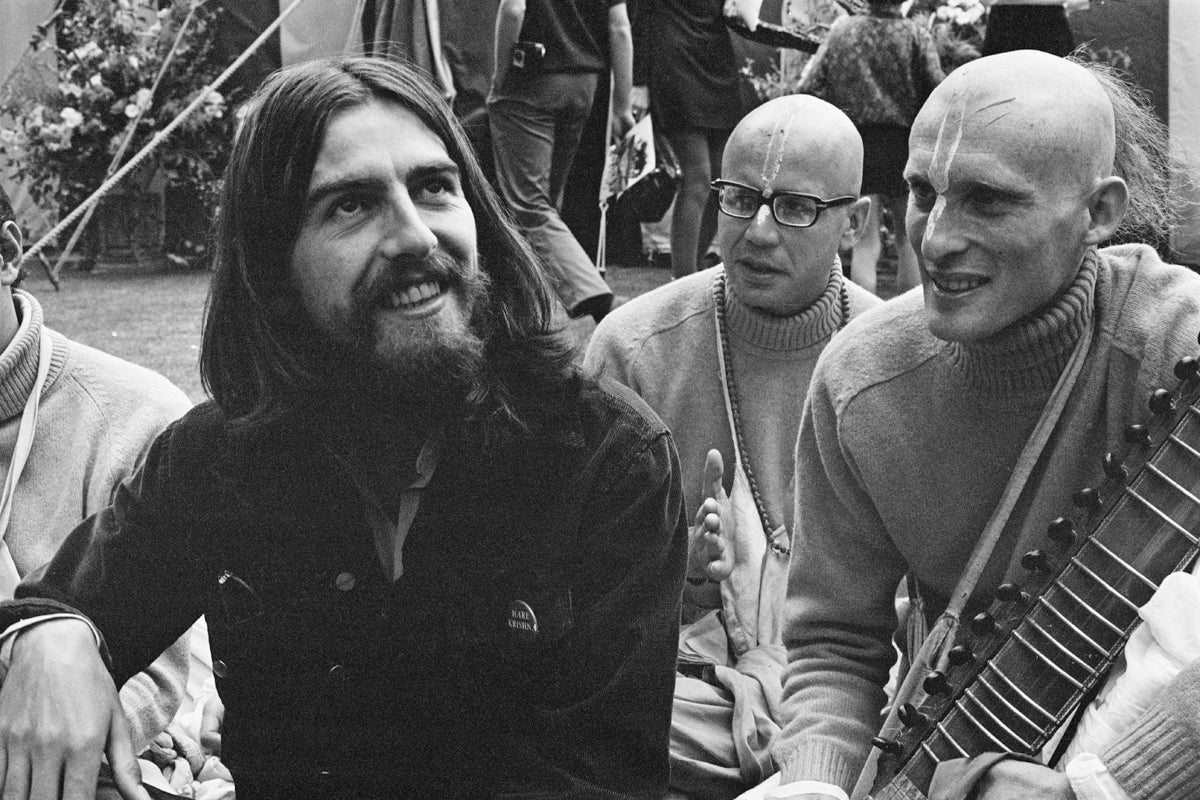

Fifty years ago “My Sweet Lord” powered to the top of the UK singles chart where it would remain for weeks, confirming George Harrison’s new status as the biggest recording solo artist in the world. All Things Must Pass had already occupied the same position in the album charts for a month. It was a treasure chest packed with the kind of Harrison compositions that the now defunct Beatles had been rejecting for years. After a decade playing third fiddle to Lennon and McCartney, the “quiet” Beatle had finally found his own voice and something he’d been craving for so long: vindication.

Resplendent in his wellies, savouring the freedom of fresh air, the album’s cover depicts Harrison with a fab foursome of garden gnomes artfully toppled at his feet. According to Harrison’s new collaborator Bobby Whitlock, the moment of true vindication came when an astonished John Lennon was “blown away” on first hearing the session tapes at Abbey Road. Whitlock remembers Harrison “beaming from ear to ear”.

For so long Harrison had struggled to break free of the group dynamic that cast him as “kid brother” to his senior songwriting siblings and at his first attempt he’d set a standard Lennon and McCartney would spend the rest of their solo careers failing to surpass. All Things Must Pass is no longer just acknowledged as the best album made by a former Beatle but as a masterpiece in its own right.

When Phil Spector was first approached to co-produce the album, he, too, had been mesmerised by its epic range: “It was endless. And each one was better than the [last].” There was so much material that All Things Must Pass became the first “true” triple studio album in rock history.

One stunned reviewer even compared his amazement to “the shock felt by pre-war moviegoers when Garbo first opened her mouth in a talkie”. But Harrison’s brilliance as a songwriter was only a revelation because Lennon and McCartney had succeeded in stifling their “kid brother” for so long.

Those tensions had always been there since Harrison had penned the promising “Don’t Bother Me” in 1963. On the event of Harrison’s premature death in 2001 an apologetic Sir George Martin admitted he’d been complicit in frustrating Harrison’s burgeoning talent.

Lennon and McCartney’s competitive rivalry was too all consuming for them to take Harrison’s early material seriously. They were “dismissive” and “indulged” him with the tokenism of a “George track” on every album.

In a candid interview given not long before his death, Lennon admitted that Harrison had succeeded despite their territorialism. He recalled how he’d reluctantly agreed to help with lyric suggestions on an early demo of “Taxman” – a song of such ominously obvious promise: “I didn’t want to do it … I just sort of bit my tongue and said OK.” Lennon admitted feeling threatened and that the songwriting partnership with McCartney was such a jealously guarded closed shop: “He came to me because he couldn’t go to Paul, because Paul wouldn’t have helped him at that period.”

As Harrison’s songwriting skills matured, they could no longer be ignored. By the time of the Beatles’ first indisputable masterpiece, Revolver, Harrison had managed to force his way onto the most fiercely contested vinyl in the history of popular music. For the first time, three of his compositions survived the cut and “Taxman” even became the lead track.

Harrison’s increasingly strained relationship with McCartney would come to define the Beatles’ final years. With hindsight you can see it as early as the Sergeant Pepper album in 1967. “Within You, Without You” is the sitar driven track steeped in classical Indian music. It’s a complete anomaly defiantly bearing no relation to McCartney’s band within a band “concept” that was meant to hold that album together.

Casual Beatle fans tend not to realise the full extent of McCartney’s influence in their gilded golden years. Without his drive and creative vision Sergeant Pepper, The White Album and Abbey Road almost certainly wouldn’t have been made. After the sudden death of the band’s manager, Brian Epstein, Lennon had struggled to maintain his interest in the band and had effectively ceded de facto leadership to McCartney.

Harrisons’s emergence as a serious songwriter coincided with the era of McCartney’s benevolent dictatorship. In an interview given much later a diplomatic Harrison described the tension with ironic understatement. It was “difficult to get in on the act. Paul was very pushy in that respect.”

I don’t want to do any of my songs … Because they’ll turn out shitty. They’ll come out like a compromise

And when Harrison started to vie with McCartney for creative control there were conspicuous clashes that made the recording of the The White Album in 1968 such an ill tempered affair. Initially, the Harrison composition “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”, had been ignored by Lennon and McCartney until Eric Clapton helped record the version that’s now regarded as one of the Beatles’ finest songs.

The decisive turning point came in November of that year when Harrison visited his hero Bob Dylan in Woodstock where he was living as a virtual recluse recording makeshift demos with his legendary backing group The Band. Harrison became inspired by The Band’s collective approach to composition and loved the way their songs magically materialised from their improvised sessions of camaraderie and friendship.

It was an approach Harrison would try to replicate within the Beatles with disastrous results. The Get Back sessions recorded at Twickenham studios in January 1969 were shelved and later re-engineered and released out as the Beatles’ underwhelming posthumous release Let it Be. Today, listening to the “fly on the wall” recordings of those sessions today is especially painful when they’re working on the Harrison composition “All Things Must Pass”. Harrison tries and fails to foster the collective creativity he’d so admired while working with The Band but the rest of the Beatles seem bemused clearly waiting for the kind of assertive lead that would be given on sessions for a Lennon or McCartney track.

Harrison is either unable or unwilling to direct the others. When it becomes clear that the track will never be finished, Harrison explodes, storms out and temporarily quits the band: “I don’t want to do any of my songs … Because they’ll turn out shitty. They’ll come out like a compromise.”

During that brief hiatus Harrison wrote a song called “Wah Wah”. The lyrics are a denunciation of the benevolent dictatorship of his senior songwriting partners: “You made me such a big star, Being there at the right time, Cheaper than a dime.” The song made clear the extent to which Harrison felt he had been made to feel pathetically grateful for his good fortune. Its ending is an assertion of independence: “And I know how sweet life can be, If I keep myself free.” Significantly, it would be the first track he would record for his new album the following year.

Harrison wrote just two songs for the Beatles’ final studio album Abbey Road, but “Here Comes the Sun” and “Something in the Way She Moves” are now regarded as two of the finest moments in their entire back catalogue.

Frank Sinatra described “Something” as the greatest love song of the past 50 years. It may have taken the band’s entire lifespan but finally a Harrison composition had been deemed deserving of a single release. Denial was no longer an option as McCartney confided to his songwriting partner. “Until this year, our songs have been better than George’s. Now this year his songs are at least as good as ours.”

But for Harrison it was a case of far too little recognition much too late. Within weeks of the Beatle’s official dissolution in April 1970, he was back in the studio working on his solo album. The symbolic significance of naming the album All Things Must Pass was not lost on his new collaborators. From the beginning of those sessions, friends and collaborators Clapton and Whitlock had seen a dramatic change in Harrison’s demeanour.

The ending is a joyous embrace of the consequences of your own actions. ‘Only you’ll arrive at your own made end, With no one but yourself to be offended, It’s you that decides’

For the initial stages of the five-month project Harrison assembled an ensemble cast of friends and collaborators. He was uncharacteristically driven, focused and disciplined as if sensing that this was his chance to put the record straight. Whitlock felt “it was like he wanted to stick it to” his former bandmates for the way they’d “rejected all those great songs”.

For all of his newfound drive, his leadership style was inclusive. After acoustic demos of his material the large band of contributors were invited to bridge their own way into his songs. Having been excluded from so many creative discussions at Abbey Road he was open to the suggestions of the contributors who spoke so fondly of those sessions. Alan White, the drummer, remembers “the really good bond” forged by collective intensity: “There was no mucking around.”

The big sound and inclusive group ethic owes an obvious debt to The Band and Bob Dylan. Its lead track “I’d Have you anytime” is one that Harrison co-wrote with Dylan and is a moving ode to their friendship. “Behind That Locked Door” is one of Harrison’s greatest songs and is an obvious homage to The Band’s distinctive alt-country rock.

That refreshing sabbatical in Woodstock had renewed Harrison’s fascination with the guitar. He had always been the Beatles’ most accomplished musician and had devised some of the most memorable lead guitar solos in the history of popular music but his riffs had always been subjugated to Lennon and McCartney melodies. But now he was free to give his talent free rein; the album saw the beginning of the slide guitar that would become his signature.

“What is Life” is the gleeful guitar-riffed stomp that Martin Scorsese chose to score the 1970s hedonism of mobsters in Goodfellas. It’s the sound of freedom. In a later self-deprecating interview he compared the glorious emancipation of that period of post-Beatles release to “being constipated and suddenly being able to get loose”.

Stockpiled rejected songs like “All Things Must Pass”, “Isn’t it a Pity” and “Let it Down” are finally given the studio time they deserved but the album’s standout moment is the truly superb “Run of the Mill”, where he shares his anger at being belittled and being made to feel second rate. Every Beatles’ session had been a missed opportunity “for you to realise me” or more often than not “send me down again”.

For too long he had allowed himself to feel as if he were “Run of the Mill”; he seems to acknowledge that he was complicit in the construction of his “quiet” Beatle persona for far too long: “Everyone has a choice, When to and not to raise their voice.”

The ending is a joyous embrace of the consequences of your own actions. “Only you’ll arrive at your own made end, With no one but yourself to be offended, It’s you that decides.” Later, it would become the favourite song of his second wife Olivia who felt it was a declaration of independence and a key staging post on George’s spiritual quest for meaning that would preoccupy him for the rest of his life.

Seven of the songs are overtly influenced by Harrison’s fascination with eastern philosophy

When it came to deciding the first UK single, “My Sweet Lord” was an unlikely choice. More of a hymn than a pop song, it subtly interchanged the refrain “Hallelujah” with “Hare Krishna” as a covert plea for greater religious tolerance before going on to namecheck a dozen Hindu spiritual leaders. Harrison had to be persuaded to release it as single and was astonished by its global success.

At 50, the song has aged as gracefully as the album from whence it came. Summoning up expansive images of air and sunlight both are perfect antidotes to the claustrophobia of lockdown. Rolling Stone lauded the album and marvelled at its epic “music of mountain tops and vast horizons”.

When Harrison died on the 29 of November 2001, Paul McCartney appeared in front of the global press to share his condolences with the world. He gave an eloquent and measured speech that was nearly word perfect. So it was perhaps a little careless to close his remarks with the one phrase guaranteed to provoke snorts of derision from his departed friend: “He is really just my baby brother.” Anyone who listens to All Things Must Pass will realise George Harrison had always been so much more than that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments