Genetic genealogy caught the Golden State Killer – but is it ethical?

Looking for long-lost family on an ancestry website could turn you into a genetic informant. And while police in the US and Europe have caught killers using genealogy databases, this controversial practice has yet to be used in Britain. Steve Boggan investigates

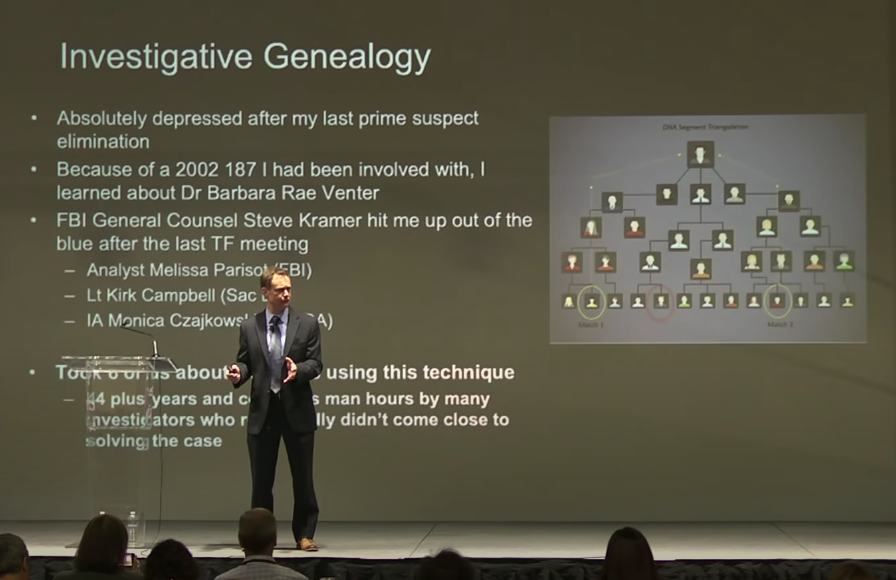

Two years ago, a wily detective on the cusp of retirement came up with a seemingly outrageous plan to catch a serial killer he had been hunting for 24 years – he would secretly plunder the fruits of personal DNA profiles shared online by amateur genealogists. In the absence of a hit on any police DNA databases, the investigator went about creating a false ID on an open source genealogy website called GEDmatch.com, and uploaded information from DNA found at the scene of a double murder. And then he waited.

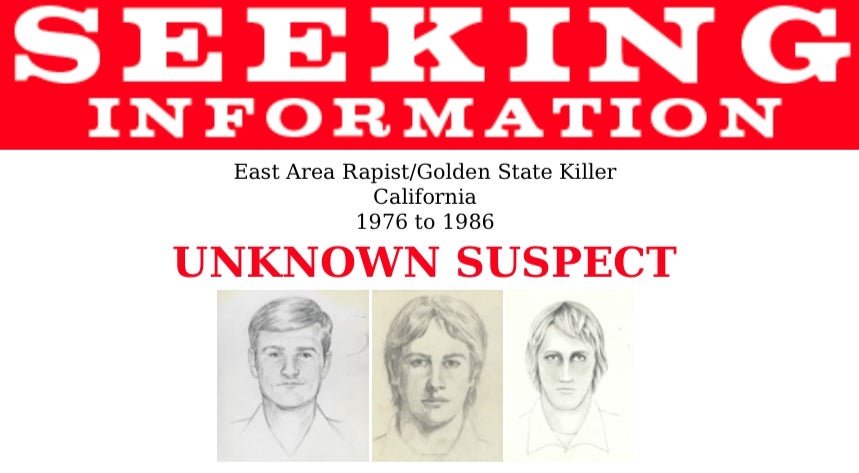

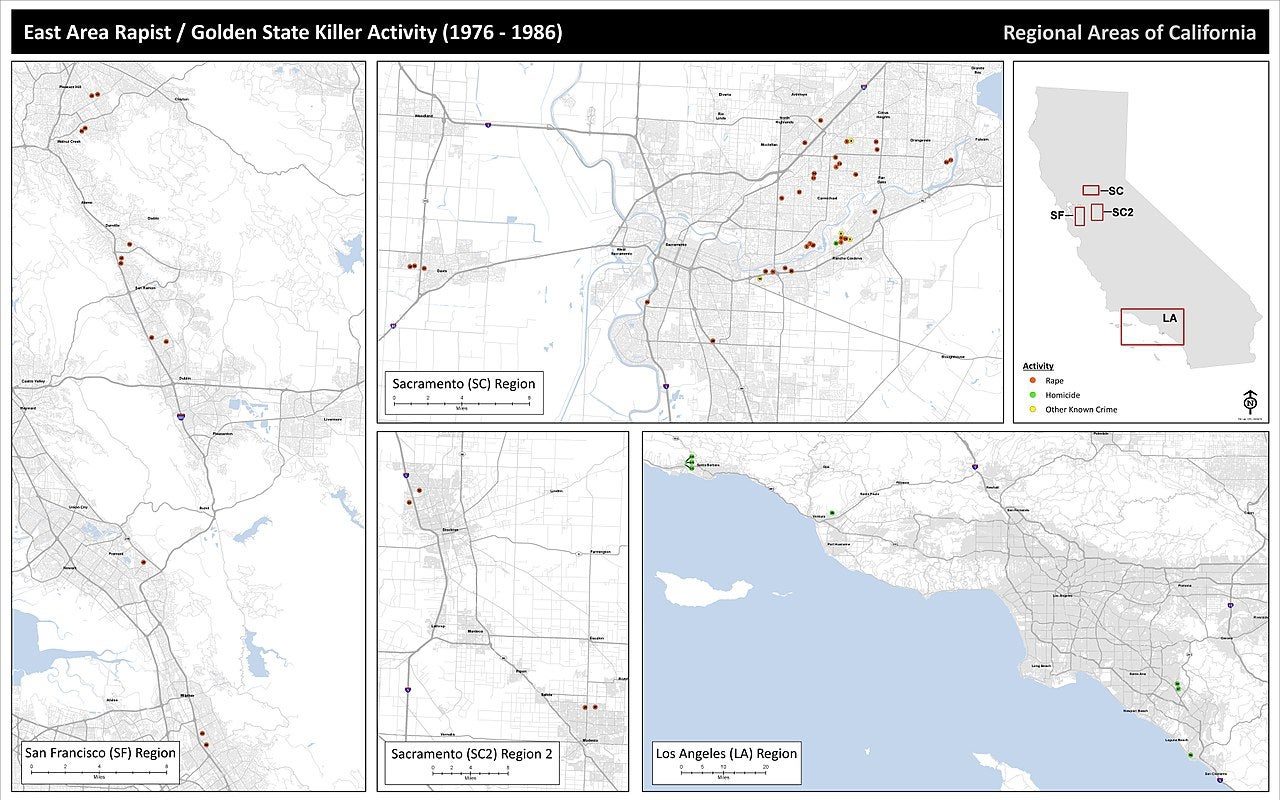

Within 24 hours, the site had identified a list of people whose DNA shared some genetic markers with the killer’s, suggesting they must be related, no matter how remotely. Then followed four months of genealogy detective work as a team led by the detective, Paul Holes, a seasoned Californian investigator, created family trees dating back to 1840 and forward to the present day until one took them to the door of Joseph James DeAngelo, a former cop who, as the ‘Golden State Killer’, had murdered more than a dozen people in the 1970s and 1980s.

This week DeAngelo, 74, pleaded guilty to 13 murders and dozens of rapes. It was the conclusion of a brilliant piece of detective work, all followed to the letter of the law without breaching anybody’s legal rights to privacy.

But to many of the people who had shared their DNA information publicly to help each other track down long-lost relatives, finding it had been used in a murder investigation has been something of a shock. Unknowingly, they have been turned into genetic informants. After DeAngelo’s arrest, law enforcement officers began to take in the potential power of this new tool in solving cold cases: they’re calling it forensic genetic genealogy, a cross between the scientific use of DNA, cross-matched with the growing amounts of public records now available online.

Others, however, have warned of a genetic Pandora’s Box being opened. Professor Stephen Mercer, a former public defender in the US state of Maryland, said at the time of DeAngelo’s arrest: “You allow that potential evidence to start being searched in these unregulated [DNA] databases, you’re casting a wide net of suspicion over many, many people.”

In Europe, police and privacy campaigners watched as some genealogy websites, including GEDmatch, revised their privacy policies, promising only to allow law enforcement to use their information where customers expressly agreed or – crucially –where the police approached them with a court order. Others, such as FamilyTreeDNA.com, made it clear to its customers that it was in favour of giving the police access to its cache of DNA information – one of the biggest in the world – to help catch violent criminals.

“The Golden State Killer case opened the floodgates for the use of this technique in the US, and we expected it to open them in Europe too, but nothing happened at first,” says Professor Turi King, the geneticist who led the University of Leicester’s identification of Richard III’s remains. “But it was simply a matter of time for it to be used elsewhere. When the DNA from a crime scene doesn’t give a hit on the DNA database, it gives the police a new avenue to pursue.

“That’s the power of this investigative approach: it doesn’t have to be the perpetrator who is in a genealogy website’s database. Distant cousins who have uploaded their DNA can also lead police to the person who committed the crime.”

Last month, it was revealed that detectives in Europe had used genetic genealogy for the first time when Swedish police announced that they had used it to solve a 16-year-old double-murder case. It now seems only a matter of “when” rather than “if” British police will be seduced by the temptation to dig into the deep well of DNA genealogy sites.

The question is whether the 4.7 million Britons who have uploaded their DNA should be worried. According to a YouGov poll commissioned by Ancestry.com last year, on top of those Brits who have already used a commercial DNA-testing service, 60 per cent of them are actively thinking about it. By 2021, more than 100 million people worldwide are expected to have provided a DNA sample to establish their ethnicity, ancestry, paternity or health prospects, according to research conducted by the respected MIT Technology Review.

That’s a lot of genetic information in the hands of a few commercial companies. The market is dominated by four main players: AncestryDNA, which has the DNA of at least 15 million people in its database; 23andMe, which has about 10 million; MyHeritage, 2.5 million; and FamilyTreeDNA, about 2 million.

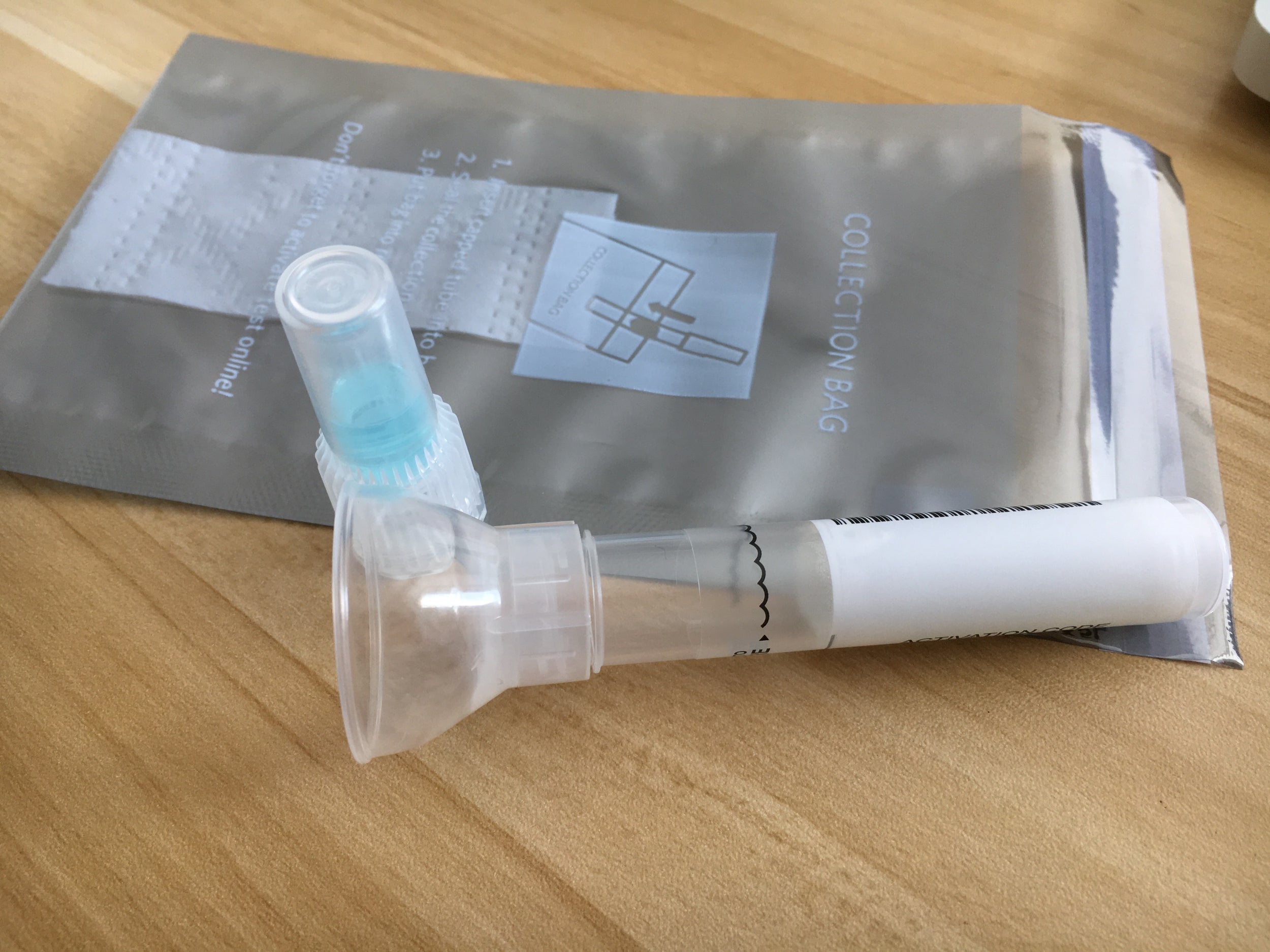

Usually, a customer provides a sample of saliva in what genealogists often call a “spit kit”. Explaining how all this works, Ancestry’s website (its Atlas spit kit costs £149) tells prospective purchasers: “Your body relies on more than 20,000 tiny blueprints, called genes. Almost every cell in your body keeps a full library of your genes in DNA molecules.

“The saliva sample that you have sent back [to the company] has cells from your mouth…Our experts use these cells to extract your DNA for analysis. Almost every cell in your body has a full copy of your DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). It looks like a twisted staircase (scientists call it a “double helix”), and it’s made up of four nucleotides: adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T).”

"Every living organism uses four-letter DNA sequences to store information as genes, which are 'hereditary': you get them from your parents. About a half of your DNA comes from your mother, the rest is from your father."

This is about as much as the average newcomer can understand. Once users begin Googling how it all works, they are likely to be overwhelmed by the mind-boggling genetic lexicon and the complex variety of analytical methods. Suffice it to say, the world of DNA testing is complicated but the websites try to make it easy for users, giving them access to a world beyond their living room and often beyond their shores.

Swedish police and prosecutors considered using genetic genealogy as soon as they heard about the DeAngelo arrest in 2018. During an interview with Radio Sweden, Bo Lundqvist, head of a police cold case review group in the southern part of the country, said: “I have a number of cases in mind to which this could be applicable.”

Yes, he told the station, there could be ethical considerations, before adding: “But if we are investigating the most serious crimes, there is probably sufficient justification. You might think its unethical, but not nearly as unethical as murder.”

There was one cold case in particular that lent itself to the technique. At around 8am on 19 October 2004, an eight year-old boy called Mohammad Ammouri was stabbed to death on his way to school in the city of Linköping, 200km south-west of Stockholm. Shortly afterwards, Anna-Lena Svenson, 56, was murdered nearby.

The killer dropped his knife and fled the scene, also leaving behind traces of blood and hair. A huge manhunt was launched, but the killer was never found. It was a classic demonstration of the limitations of DNA in solving crime: without having something or someone with which to compare it, it is useless.

When he heard that police were considering using genetic genealogy to try to crack the case, Peter Sjölund, one of the country’s foremost experts in the field, contacted the head of the investigation, Jan Staaf, to ask if he might help.

“I was fully aware of the case of the Golden State Killer but the technique had not been used in Europe and I wondered whether it would be,” he tells me. “Then, a year ago, I heard that Swedish police were thinking about trying it. I contacted Jan Staaf, and asked if he could use my help and, straight away, he said yes. That was last September [2019].

“First, we started with DNA the police already had but it was not good enough quality to use. When the police investigate, they test for 15 markers. Genealogists like me test for 750,000 markers, so we had to start from scratch and piece together better-quality DNA from hair, blood and so on, collected at the scene. That process started at the end of 2019 and was finished at the end of April, so it took about four months; the genealogy side of it took just five weeks.

‘We looked at GEDmatch but didn’t get any workable matches there. Then we tried FamilyTreeDNA and got around 900 matches of people who were related somehow to our man. Of these, 860 were extremely distant – maybe dating back to the 16th century – but 15-25 were quite good, relating to people in the late 18th century and early 19th century.

“From those, I started to identify all the people from the genealogy website. Some of them had completed family trees, while others were just names and email addresses. When I identified the best matches, I started drawing up their family trees and mapped 600-700 people from the Linköping area and found common ancestors back in the 1790s and 1820s.

“The perpetrator was descended from some of these so then I started searching forward to see where family trees intersected right down until I found living people, men born in the 1980s. At that point there were fewer than 10 men that could be the perpetrator.

“I then had to turn it around and map all of their family trees to see which ones intersected at all the right points. Once I had done this, and excluded people who were dead, there were only two brothers left.”

Sjölund had spent hundreds of hours growing his trees and then pruning them. Mostly, he worked out of an office in the local police station among detectives who often admitted they didn’t quite understand what he was doing. Now, in front of him, he had two names. It was a Friday evening and Jan Staaf was attending a graduation reception.

“I called Jan and said ‘I’ve found him. He’s one of two men’ and then it was his job to establish which brother it was. The police made preparations and on Tuesday morning they arrested the most likely brother and brought in the other one to give evidence. They tested both brothers’ DNA and one was a 100 per cent match to the DNA found at the crime scene.

“Jan was amazed that I had done it, and done it so quickly. I had conducted most of the research at the police station and he would come into my office and ask me what I was doing, but he said he couldn’t follow most of it. Even I was amazed by how quickly things moved in the week before I identified the suspect.

“The important thing to realise about this method is that it is a much more powerful genetic tool than those available to the police at the moment. The UK and Swedish police have their own DNA databases but they only work if there is an exact match or someone on it who is a very close match, such as a family member.

“Using genealogy databases, you can find matches as far away as sixth or seventh cousins and trace family ties going back hundreds of years. It is a completely different universe and a much more powerful tool.”

Using genealogy databases, you can find matches as far away as sixth or seventh cousins and trace family ties going back hundreds of years. It is a completely different universe and a much more powerful tool

Genetic genealogy is going to solve a lot of cold cases, so why should anybody be concerned? The families of the Swedish victims now know who killed their loved ones: the 37 year-old brother who was charged has yet to be convicted but he has confessed to the murders. Surely, questions of privacy should pale into insignificance?

In an interview about the Golden State Killer case, Paul Holes, the detective who cracked it (with the genealogist in his team, Dr Barbara Rae-Venter) was asked about the “closure” he had brought to victims of rape and the families of the killer’s murdered victims. He replied: “You know, this is an interesting phrase – closure. Whether you talk to surviving victims or families of the victims that were killed, they never feel closure, because no matter what, they’ve suffered a tremendous loss or a tremendous trauma.

“So, instead of using the term closure, what I say is that I’m bringing them an answer. They now know who attacked them or they know who killed their loved one, and that is huge to these people, because up until this point in time – 40 years in some instances – it’s been a big unknown, and some of these living victims have lived in fear that this guy was still out there and he was going to come back and get them.

“So, for them to understand who it was is a huge thing and a relief, and I experienced that relief first-hand in being able to tell them ‘We got the right guy. No question about it. And he’s never going to get out again’. And some of these victims just started sobbing from that relief. Biggest reward I’ve ever had in my career was talking to some of these victims.”

And yet, privacy and the security of something as precious as genetic data do matter, and not just to the people who consented to its use on DNA genealogy websites. It is also important to their relatives who didn’t consent.

“When you upload your DNA, you aren’t simply uploading your own, but members of your family’s too,” says Debbie Kennett, honorary research associate in the Department of Genetics, University College, London. “You share 50 per cent of your DNA with your siblings, 25 per cent with your grandparents and smaller percentages with second, third cousins and so on.

“So, you aren’t just putting your own DNA out there, possibly to be used in police investigations. You’re putting theirs out there too, without necessarily having their consent.

“In the US, this has led to some investigators pressuring people into uploading their DNA on to websites because they have been flagged up as a result of relatives who chose to upload. The police don’t necessarily see them as suspects but as people whose additional DNA might help them close in on a perpetrator.

“They call it ‘target testing’ and sometimes this has been done with a lack of respect. Individuals have also been harassed for information about their relatives. And once people take unintended tests, they could find out that their father isn’t their father or other family secrets could be uncovered.”

Professor King says: “Consent is a big issue. People are generally quite happy to use the DNA testing service and database matching to look for potential relatives. This doesn’t give away a person’s raw DNA sequence; it shows that people match at certain segments of their DNA. What matters here is whether people who have their DNA tested by these testing companies agree to have their DNA used by law enforcement for forensic cases.

“Another angle to consider, and this is true of all DNA databases, is how is a person’s genetic data being kept and used? How safe is it and who can use it and for what purposes? These need to be transparent so people can make informed choices.

Police were only able to get away with using the website because it had a very loosely worded privacy policy that warned users that it wouldn’t be responsible if uploaded DNA information was put to uses that hadn’t been thought of yet

“So, it’s a fantastic technique, but I think there needs to be discussion and for there to be a team of experts in this area working with the police around its possible use.

GEDmatch was so important in all of this because it was a unique, free, open-source website on to which people could upload their DNA information, regardless of whether the original test was conducted by Ancestry, 23andMe, FamilyTreeDNA or any other. It served as a kind of clearing house for genetic genealogy buffs to try to find relatives.

Police were only able to get away with using the website because it had a very loosely worded privacy policy that warned users that it wouldn’t be responsible if uploaded DNA information was put to uses that hadn’t been thought of yet. And its founders hadn’t thought of the police using a fake ID and uploading DNA from a crime scene in order to mine its resources.

The backlash from genealogists after the Golden State Killer case let to the site promising not to allow police access to members’ information unless they specifically opted-in to agreeing to do so. Of 2.1 million users, only 200,000 have subsequently agreed their information can be used in criminal investigations.

All the other sites tightened up their privacy policies too, most promising not to give access to law enforcement unless legally obliged to. Already, though, there have been a number of cases where search warrants were produced and information supplied. Ultimately, then, opting out would appear to provide no guarantee of complete privacy from the law.

In an indication of what can happen when you give your information to one entity only to see it in the hands of another, GEDmatch and all its DNA databases were bought in December last year by Verogen, a commercial company servicing, among others, the law enforcement sector. Verogen’s CEO, Brett Williams, says the company plans to stick to its “opt-in” only policy but he admitted there wasn’t much it could do if the police came knocking with a court order of some kind.

“If it is a valid search warrant you cannot not comply,” he tells me. “However, we would look to see if it was a dragnet operation or carefully targeted, and if it was just a fishing expedition, we would most likely fight it [in the courts], particularly if it impacted people who had not opted in to having their information used by police.”

He says things are picking up in terms of people opting-in their DNA for police use. This, he thinks, is as a result of a popular and recent ABC documentary series called The Genetic Detective, which features cold-case resolutions using genetic genealogy (and which is coming to the UK soon).

“Since the default setting for the site was taken back to opt-out in 2019, about 80 to 85 per cent of new customers have opted in to allowing their DNA to be used by the police,” he says. “I’m not sure how many of the existing customers – the ones who originally signed up to find their relatives – have opted in, but it’s less, and that’s their choice. I always point out that people can use an alias or a one-time email address to use our service and that means they won’t be identified even if the police got a warrant.

“You have every right to privacy, but you also have every right not to get murdered or be sexually assaulted. From a societal perspective, it is an individual’s right to decide how much they want to participate in this. There will always be people whose sense of civic responsibility leads them to opt in.

“And let’s not forget that this results in people being exonerated, too, so it cuts both ways. When you use this kind of technique it leads you down a route where you finally have to confront an individual with your evidence and make a DNA comparison. If that doesn’t match, then you’ve got the wrong guy. You can’t have false positives using this.”

Aside from the tightened-up privacy policies of the genealogy companies, your DNA information is protected by European and British data protection laws, which are supposed to prevent it being shared willy-nilly. That means it is theoretically private unless you opt in to law enforcement usage – or law enforcement uses it regardless with the say-so of the courts.

For now, police in the UK say they haven’t used genealogy websites for investigative purposes, arguing that they are happy with the UK National DNA Database, which contains the DNA of six million citizens.

When I asked the National Police Chiefs Council if genealogy websites might be mined in the near future, it said: “The guidance from the NPCC is that forces do not use commercial genealogy databases in UK criminal investigations,” before adding: “However, forces are operationally independent of us, so it is guidance only.

”Concern in America over the use of genetic genealogy in the Golden State Killer arrest and the introduction in Europe the following month of the General Data Protection Regulation, which demands opt-ins, has slowed down the growth of the sector. Some industry reports claim sales of DNA test kits are down by more than 50 per cent.

This, according to UCL’s Debbie Kennett is not a bad thing. Before sales pick up again – as they surely will – it will give us time to ask how we see our collective genetic future. “Maybe we need something like a campaign to raise people’s awareness of how their DNA could be used, now and in the future,” she says. “Perhaps there should be something like a citizens’ jury where members of the public with different views could debate the advantages and disadvantages.

“We need consent from the whole of society over how our genetic material is used, rather than from just a few people who run these websites and databases.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments