In a multilingual world, gendered language is the last stronghold of binarism

Research shows that countries with gendered languages lag behind in gender equality. It’s only a matter of time before what was once deemed ‘wrong’ is accepted as ‘right’, writes Heather Martin

It was a terrific line of poetry, guaranteed to blow the teenage mind in French class. “Je est un autre.” I is another. So wrong, but also so right. The messy complexity of lived experience running up hard against the clear-cut confines of grammar. Writing in the 19th century, French poet Rimbaud was ahead of the game. Pronouns were a problem. Whitman agreed. “I contain multitudes,” declares the “Song of Myself”.

I am not (or not only) the person you see. I am not (or not merely) the person you want, or need, or require me to be.

More immediately, “I” – as first-person pronoun – am/is ungendered. And so too are “you”, the multitudinous individual I am addressing. At least in English, and other so-called “natural gender” languages. Writing in the third person, by contrast, I, the author of this article, had to work hard in that second paragraph to avoid gendering those two poets by lapsing into use of “his”, or their gender-infused first names.

In French, or Spanish, or German, or Russian, or any other grammatically gendered language, it’s harder still. Even as a kid in school I found the novelty of “girl” and “boy” nouns paled pretty quickly. How tiresome it seemed that the girls were always second in line, along with all those neatly matching, colour-coordinated adjectives in their annoying lists of pink and blue.

Depending on how you look at it, those compliant adjectives – “agreeing” with the noun every time! – may be commendably cooperative or timidly submissive. But either way: secondary. Nineteenth-century French novelist Georges Sand wasn’t having it. I am a mother, Sand wrote in letters to Flaubert – while simultaneously eschewing all feminine forms of language.

Later, as a fully-formed linguist, I was seduced – and distracted from issues of equality – by the chimerical certitudes of grammatical rigour. Grammar was either right or wrong: you could hang your pink or blue hat on that. It was a relief in an increasingly uncertain world. Then when I began teaching Spanish to primary school children it became a point of principle to use “correct” terminology from the start. My whole philosophy was founded on confidence in their ability to rise to my belief in them: to shy away from abstract concepts would send out completely the wrong message.

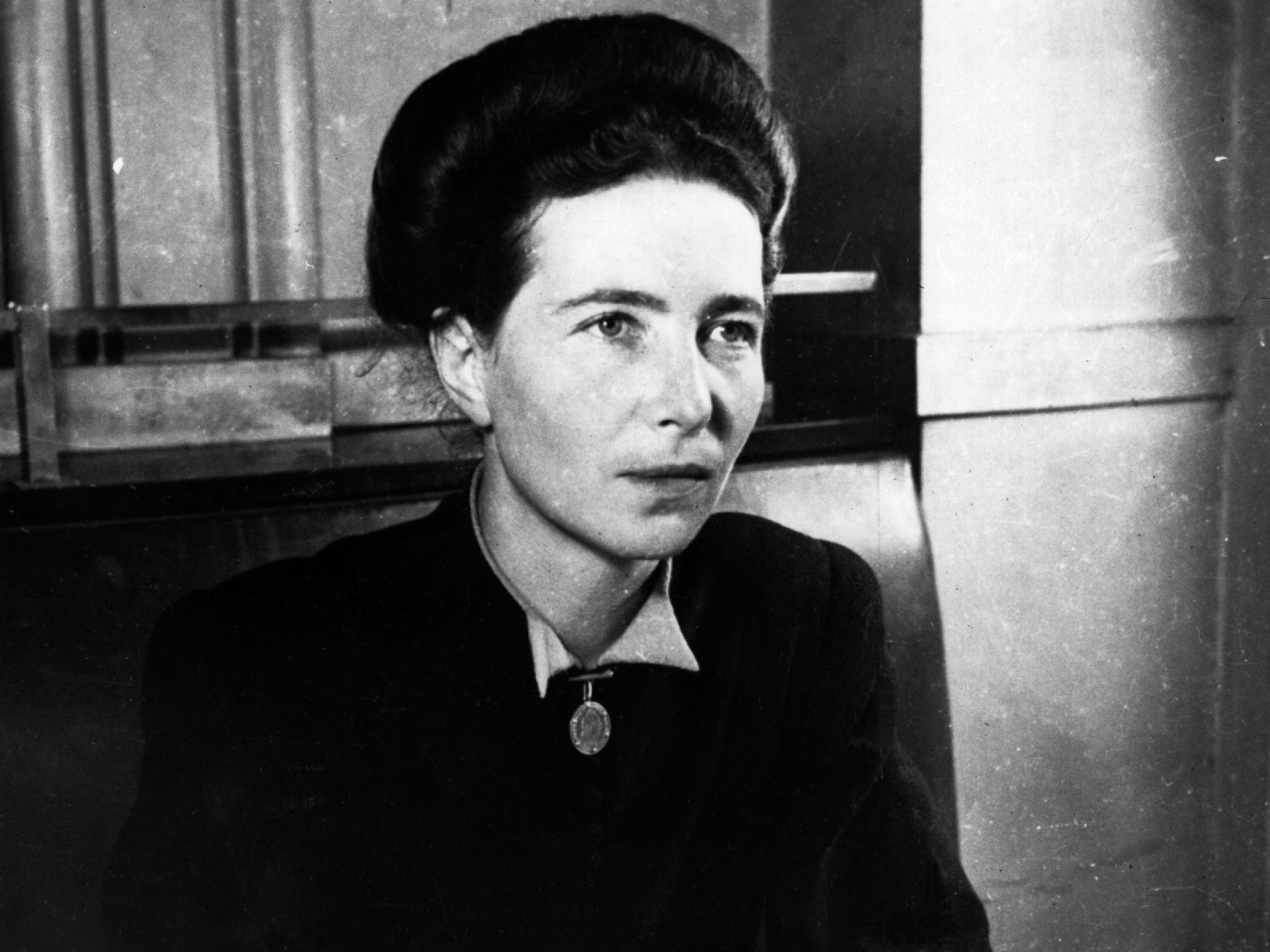

So I embraced both masculine and feminine and gave them equal billing on the page. Well, almost equal. The masculine still had pride of place on the left. The masculine was what you attended to first. On the face of it innocent, but in essence socially and culturally loaded. As Simone de Beauvoir wrote in The Second Sex: “Man is defined as a human being and woman as a female.” An add-on or ornament, a quasi-adjectival adjunct.

There was good pedagogical reason to follow the convention. It seemed as fundamental as putting the units to the right of the tens in mathematics. Tidy habits make for a tidy mind. But the truth was it didn’t really matter – except in one, very human way. Swap the order and linguistically nothing changes. But sociologically, it’s a revolution.

Like water, languages will always seek out the easiest route. Like gender, they are intrinsically fluid

It could be that gendered languages are among the last strongholds of gender binarism, and that scrupulous teachers are unwittingly colluding in perpetuating this reductive, anti-egalitarian paradigm. There are few contexts in contemporary western culture where it is still legitimate to speak unselfconsciously in terms of “masculine” and “feminine”. What useful meaning does this opposition retain? We are all more at home on the spectrum.

Maybe it’s an accidental byproduct of our compulsion to classify. But even if you argue, along with Saussure, that linguistic signs are arbitrary, that there is no necessary connection between the signifier “table” and the object it signifies, that a table might as well be labelled a chair (with no necessary reason for either of them to be either masculine or feminine), there is no escaping the semantic resonance that accrues to words over centuries of use and abuse. And no denying that gendered languages endorse a persistently gendered mindset. Grammar can be arbitrary too.

Fortunately, even at an elementary level, there are ways to subvert this absurd grammatical binarism to thought-provoking ends. Look, I told the children in my class: the Spanish noun for “people” is feminine! So too “reason” and “intelligence” and “compassion”. But yes, “love” is masculine – imagine that! And look: your hair and eyes and lips are all masculine, but your nose and mouth and ears are feminine! Where does masculine you end and feminine begin? There is no hard-and-fast division; we are all a muddle of X and Y.

As Wittgenstein said, the limits of our language are the limits of our world. Research shows that countries with gendered languages lag behind in gender equality, and that female migrants to the US who speak gendered languages exhibit lower labour force participation, with larger effects for languages with more pervasive gender elements.

At word level, a 2002 study out of Stanford University explores how the common noun “bridge” attracts different responses among German and Spanish speakers: die brücke (feminine) is perceived as “pretty” and “fragile”, el puente (masculine) as “sturdy” and “strong”. Tired associations, as burdensome to men as to women. When a word has two genders, as in the German “leiter”, the masculine referent (“leader”) is almost always more overtly powerful than the feminine (“ladder”).

Sweden introduced the gender-neutral pronoun “hen” in 1966 (formally recognised in 2014). West Germany banned official use of “fräulein” in the early Seventies; the title “Mx” appeared in the US later that decade. The avant-gardistes of the University of Leipzig now insist on the feminine plural for mixed-gender groups – one giant leap for humankind in stemming the tide of patriarchy, but a stone wall, a dead end for the non-binary.

The laudable trend towards feminisation throws up its own problems. In French, for example, it frequently undermines its own good intentions by carrying overtones of sexualisation, as in “maitresse” (for teachers), or “danseuse”. A “rouleur” is a racing cyclist, a “rouleuse” a “femme facile”. “Woman” is always already inhabited by the potential value judgement, “loose”.

In 2017 France published its first linguistically inclusive textbook. The objective was to promote use of the “middot” (was that unhyphenated neologism French or English, or something more indeterminate on the spectrum?) – or “median-period” – at the end of masculine nouns, followed by the feminine ending, and if required, the plural too, as in: musicien.ne.s. Prescriptivists denounced the initiative as an act of vandalism, and those responsible for it as idiot.e.s, but professor of Renaissance French Éliane Viennot retorted with a simple argument: “Telling children the masculine form wins over the feminine cannot contribute to shaping egalitarian minds.

The political case for the middot is incontrovertible. The practical problem is the way it clutters up the page. Marie Kondo would not approve. The well-intentioned punctuation mark, theoretically unobtrusive, makes the language harder to read, harder to spell, and harder to pronounce. A giant leap forward, but several steps backwards as well. Antithetical to the counter imperative towards simplification and plain-speaking, it was never going to fly.

Spanish has made creative use of the economical “at” symbol. “Chic@s” and “latin@s” send out a strong visual message but also trip off the tongue – “chícaos”, “latínaos” – with the added value of reversing the old world order by putting the feminine first. It’s a neat, but partial, solution, limited to words whose dictionary form ends in “o”. The popular “latinx” can be pluralised – “latinexes” – according to the natural laws of the language.

Specious objections that the designation is current only in the States, and by definition “othering”, ignore the reality that the country is by definition multilingual, with English and Spanish nurturing and nourishing each other in ways no border wall can obstruct or contain. In Spanish it is already commonplace to use the verb without a subject pronoun: perhaps they could eventually do away with pronouns altogether?

Like water, languages will always seek out the easiest route. Like gender, they are intrinsically fluid. Which is why in English use of singular “they” – as in “they are Sam Smith, an English singer-songwriter” – has won out over the more alien, disorienting neologisms “ze”, “hir” and “xem”. French already has the gender-neutral “on” (less pompous than our haughty “one”), from the Old French “hom”, which narrowed into “homme” or “man”, but derives originally from the more inclusive Latin “homo”, for “human being”.

Perfection is not in the nature of language because it’s not in the nature of human beings. But imperfection has the virtues of its vices. Unlike mathematics, languages are inconsistent and self-contradictory, but also tolerant, inclusive, and endlessly accommodating

In the schoolroom, languages aspire towards a binary, black-and-white accuracy. Increased accuracy will get you more marks, better grades, entry to a better university, a higher class of degree. But that’s not the real world. It’s all well and good to strive after perfection, but only if you accept that it’s not only unachievable but undesirable.

Perfection is not in the nature of language because it’s not in the nature of human beings. But imperfection has the virtues of its vices. Unlike mathematics, languages are inconsistent and self-contradictory, but also tolerant, inclusive, and endlessly accommodating.

You want “sick” to mean “great”? You prefer “me and my friends” to “my friends and I”? Fine, we can adapt. You want to drop the preposition “on” after the verb “to impact”? OK, why not? Less is almost always more. Hasn’t Latino Spanish dropped the “al” from “jugar [al] fútbol” (“to play football”), to go with the English flow?

Why not meet halfway? We do it all the time, out of empathy, or a desire to fit in, moulding our forms of speech to the rhythms and patterns and eccentricities of those around us. Parents copy children. We all copy those exemplary multilingual athletes who have so gloriously demonstrated that “I played good” gets the meaning across just as effectively as “I played well”. Mistake the gender of “baguette” and even the most pernickety of French boulangers isn’t likely to refuse the sale. Understanding may be enhanced by accuracy, but only rarely depends on it.

This is perhaps the greatest single benefit of multilingualism: a general increase in mutual tolerance, both human and linguistic, not exactly laissez-faire, but a live-and-let-live attitude towards our shared fallibility. Better to speak more languages imperfectly than to be mistress of a paltry one. In opening our minds to other cultures we learn to expect the unexpected, which better prepares us to embrace difference in our own.

It may be a headache for editors, but we need to be more open to experimentation and more interested in error. Play is the mother of invention. Nonsense can lead to new – and better – sense in the long run

Which is why, on a recent trip to Cambridge, it was so exciting to stumble across a pop-up museum of languages in the middle of an otherwise unremarkable shopping arcade. The Cambridge University brains behind this innovative concept seek to address anyone from four to 84 (why stop there?), but on this particular Saturday, the average age was around eight. Which seems about right: there is no more important target audience. We can learn a new language any time. It’s never too late to open our minds. But the sooner the better.

The first-of-its-kind World of Languages pop-up museum isn’t concerned with preservation, though there is a case for that. As recently as the turn of the 21st century, according to language activists Wikitongues, “as many as half of all languages were in danger of disappearing, a canary in the coal mine of humanity”. Now, they argue, we are “pushing back against forced assimilation” amid “a renaissance of linguistic and cultural diversity”, breathing life into the otherwise hollow oxymoron “global community”.

But despite this empowering vision, we are still erecting political barriers. The World of Languages invites us to transcend them. On the tried-and-tested model of the science museum, its interactive displays spark the sense of discovery that goes hand-in-hand with learning any new language: a lost-in-translation untranslatable word quest, a pool of creatures carrying words loaned to English (“emoji”, “rucksack”, and “graffiti”), a “language family” street and an “I love you” language line.

Our complacent reliance on the apparent dominance of English is sadly misplaced. Around half the world’s 8 billion people speak one of just 10 (out of more than 7,000) languages; more than 75 per cent do not speak English at all; more people are bilingual than not. We in the United Kingdom, despite the privilege of living in a richly multilingual country, are missing out. Eventually, we run the risk of being left behind, not least in trade, business and diplomacy.

It was the study of other languages, I realised, that first introduced me to the possibility of other pronouns, that induced in me a welcoming state of mind. “I” was no more or less legitimate than “je”, “yo”, “ich”, “io”. And depending on the pronoun I adopted, I was a subtly different iteration of myself, more or less tentative, assertive, reserved or demonstrative. “I” contained multitudes; “I” was another.

Unless we all opt for non-gendered Finnish, or Estonian, or Chinese, languages – and language-learning – must be allowed to get messier. It may be a headache for editors, but we need to be more open to experimentation and more interested in error. Play is the mother of invention. Nonsense can lead to new – and better – sense in the long run. Creative error is not the exclusive preserve of poets. It’s only a matter of time before some of those mistakes catch on, and what was once deemed “wrong” is accepted as “right”. Grammatical accuracy was never a guarantee of understanding between human beings. We know that from experience.

In the pop-up museum there is a listening station where a passage from Lewis Carroll’s quintessentially English Alice in Wonderland is read by seven different non-native English speakers. But no two “Englishes” sound exactly the same. Languages have different sound systems, and speakers naturally transfer some distinctive features of their hard-wired pronunciation to the new languages they learn. We should rejoice in that. The more widely a language is spoken – English, Spanish – the more fluid and accommodating it is destined to become, and the more resilient it will be.

No doubt language teachers will go on using the time-honoured terms “masculine” and “feminine”. But they can no longer do so innocently or unquestioningly. If they do, we should expect them to be challenged by their pupils. And should a class member offer the feminine plural for a mixed group of nouns, instead of the masculine as convention demands, we can no longer crudely dismiss it as “wrong”.

Once upon a time, we might say, that would have been deemed incorrect. But no longer… now, it is one among a legitimate spectrum of possibilities. Grammar is fluid. The languages you speak belong to you. It’s down to you to expand the possibilities further, to extend the limits of your world. It’s OK to care about pronouns. But people matter more.

Dr Heather Martin is an independent scholar and linguist

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments