The Glamour Boys: How a group of queer MPs fought the good fight against Hitler

In his book ‘The Glamour Boys’ Chris Bryant tells the story of a group of gay MPs who were openly supported by Churchill and fought back against the Nazis. Ed Prideaux reports

Hitler’s march through Europe appears unstoppable. Having invaded Czechoslovakia and annexed Austria, the Third Reich is placing British “appeasement” under chronic and humiliating duress. Prime minister Neville Chamberlain, the policy’s architect who is convinced of the public’s appetite for peace, is worried. His agreements with Hitler aren’t working.

And while he commands a strong current of support among Tory MPs – and an overwhelming coalition majority against Labour – a secret group of MPs is sowing discord behind the scenes. Calling for war and sounding repeated alarms about Hitler’s ambitions and abuses, the group is proving a nuisance. Chamberlain’s not sure what they’re planning but his master of dark arts, Sir Joseph Ball, is keeping tabs.

They call them the glamour boys – so-named because around one-quarter of their membership is homosexual, bisexual, or somewhere in between. Chamberlain and Ball are careful not to make public accusations without substance but “glamour” – with the phrase helpfully repeated in Westminster circles and by favoured journalistic connections – carries much of the curse. Glamour means effeminacy, vanity, anything to sustain Britain’s homophobic stains at the time. And despite Chamberlain’s escalating sabotage campaign, the glamour boys are only growing in influence. It’s just a matter of time before the guns start firing.

The tale of Britain’s entry into the Second World War is part of our national memory. We all know the story. The attempts at appeasement, the limp-wristed foibles of “Peace In Our Time”, Churchill’s succession, the “Phoney War”, Britain’s singlehanded opposition – and eventual victory – over the Nazi menace: it’s a story pumped into schoolchildren, undergraduates, and the general public alike every year in a well-oiled cultural machine. It’s a story with 75 years of pedigree and devoted practice. It’s unlikely ever to go away.

It’s also unlikely, however, that any of you will have heard of the glamour boys. Even fewer will have known that many of them were queer. It’s equally unlikely that the policy of appeasement, and our entry into the war, had ever been conceived as signposts in Britain’s LGBT history. But the facts tell us something quite different.The Glamour Boys, a new book by Chris Bryant, Labour MP for Rhondda and former Shadow Leader of the House of Commons, promises to revise everything we thought we knew. The boys’ queer identity wasn’t incidental, either. Their sexuality – forced into hiding by Britain’s rampant homophobia – motivated an empathy with Germany’s oppressed queer community and other victimised minorities, and one that led them to call the first and enduring warning shots over the Nazi threat. Yet it would consign their role to the historical dustbin.

“My basic point is that I want us to know the full story,” Bryant told The Independent. “It wasn't just Churchill who got us to oppose Hitler. Quite often when Eden and Churchill were gathering with the rebels, they were the only completely heterosexual men in the room.”

The glamour boys’ revolving cast counts a few key names. There’s Jack Macnamara, a military man who’d landed in trouble in Tunisia for a misunderstanding over a gay encounter. Ronnie Cartland, the brother of novelist Barbara Cartland, had been to Charterhouse and moved up the ranks of the Conservative central office. Victor Cazalet was a hero of the First World War, as was Harry Crookshank. Robert Bernays was tall, handsome, part-Jewish, and worked as a journalist before entering politics.

Philip Sassoon, a member of the celebrated Jewish Sassoon dynasty, had also served in the war. Bob Boothby, a parliamentary secretary to Churchill, became later-known for his affiliation with the Kray Brothers. Harold Nicolson was the oldest of the bunch, and a veteran in Middle Eastern diplomacy.

Yet despite their differing ages and disparate backgrounds, the glamour boys had a core secret in common. British life in the run up to the war was simply no place to be gay. The “abominable crime of Buggery”, the book describes, “attracted a penalty of penal servitude for life, or at least 10 years”. Gross indecency, a related charge, could get its commissioners two years inside with hard labour.

Responding to a legal challenge on “soliciting men for immoral purposes”, the Court of Criminal Appeal declared that “if ever there was a case for corporal punishment, it is for that particular class of offence”. A new Criminal Law Amendment Act gave “incorrigible rogues” two years with hard labour.

Despite liberalising pangs of cultural change, especially for women, moral panic was making the problem worse for Britain’s queer community. In London alone, The Glamour Boys shows, convictions for homosexual offences rose by more than 90 per cent from 1922 to 1937.

“You were terrified,” says Bryant, who is one of Westminster’s few gay MPs. “You couldn't write a letter to anybody because that might be inciting somebody to commit an act of gross indecency. You couldn't hold his hand. You were given advice not to be too meticulous about your clothing in case people might suspect something. You had a language of your own.”

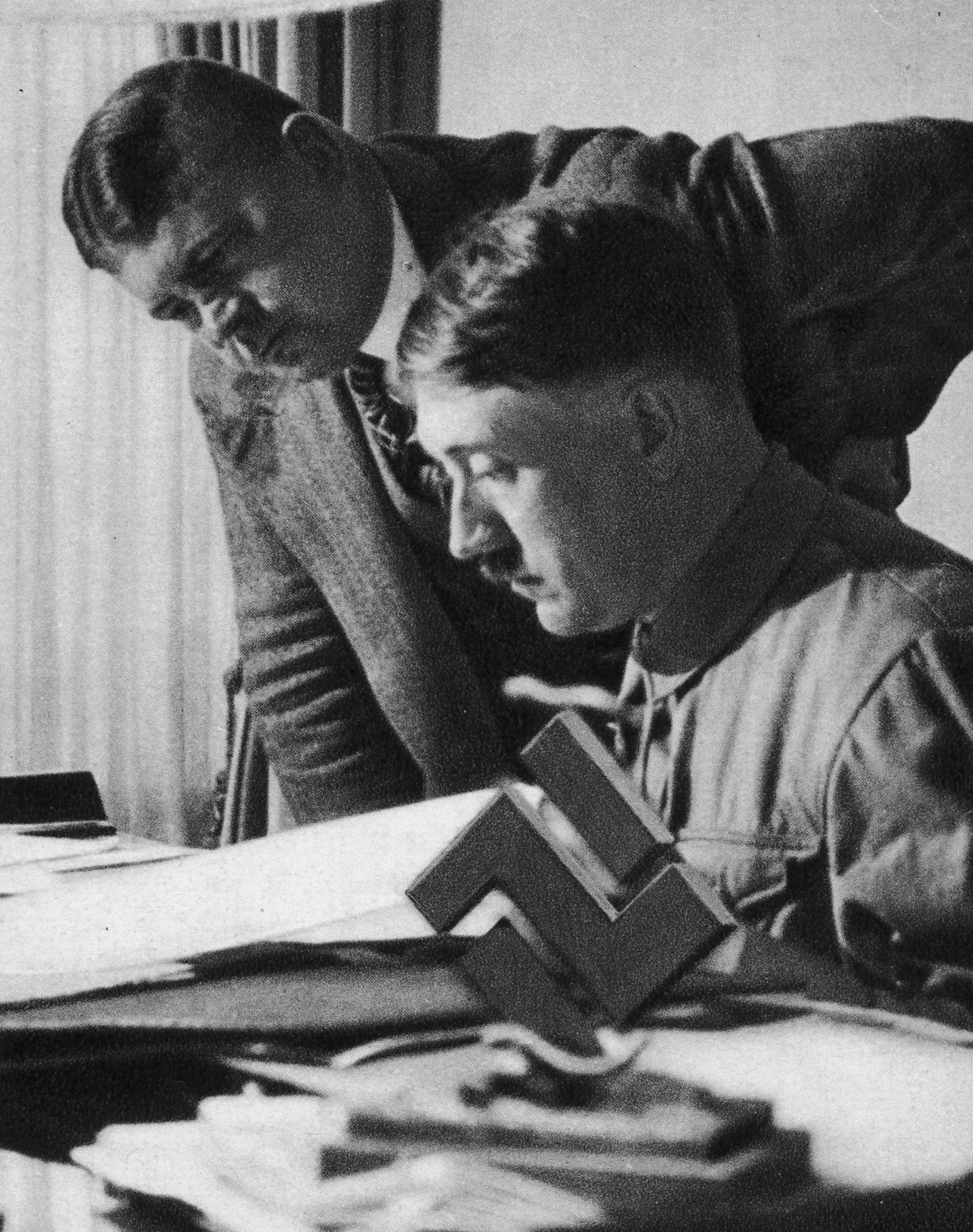

Ernst Rohm made frequent visits to the Eldorado gay nightclub where he mixed with Jack Macnamara MP

Unsurprisingly, Britain’s social climate led many queer men to look elsewhere. The destination of choice was often Germany. It was “a bugger’s daydream”, one contemporary wrote. “Berlin meant boys”. Following a relaxation in the legal environment, Berlin enjoyed an oasis of liberated sexual culture. Bars, cafes, nightclubs, Turkish baths and salons were open for all, and provided men around the world – including the glamour boy MPs – with the freedom finally to express themselves.

For the boys, trips to Germany would sometimes double as gay holidays and diplomatic missions, during which they became gradually awakened to Germany’s changing political character. Bob Boothby, for example, would found the Anglo-German Association, a consortium of MPs and Westminster change-makers who sought to normalise relations with the Weimar Republic. Boothby and the AGA were especially concerned about the ongoing effects of the Treaty of Versailles, a punitive agreement signed by Germany after the First World War that devastated its economy, gutted its industry, and stole away nationally important land.

Against the backdrop of a “gradually increasing desperation”, Boothby recognised the energetic appeal of “Hitlerism”. He even liked Hitler on their first meeting. Another glamour boy, Rob Bernays, felt the same. Hitler’s beliefs and hatred notwithstanding, something about his oratory, his charisma – which Bernays likened to a “prophet” – was darkly attractive. It only goes to show that surface sheen really can subvert the mind.

Hitler’s passion worried Bernays, though. Returning home from Germany, he was one of Britain’s first public figures to sound the alarm, and a full seven years before the outbreak of war. “In Germany today,” Bernays said in a local meeting, “there are all the elements of a resurgent militarism.” And after another trip in September 1933, Bernays emerged disgusted with the Nazis’ escalating violence towards Jews. He wrote articles and op-eds in major nationals to make the case. “If this spirit is allowed to continue”, Bernays wrote in November, “It means war in 10 years.” His only mistake was time.

Being that some Nazis were gay, a few glamour boys were acquainted more deeply with the early movement. Ernst Rohm, the puggish, facially scarred head of the SA brownshirts, made frequent visits to the Eldorado gay nightclub, where he mixed with Jack Macnamara. And while Hitler initially acquiesced to Rohm’s adventures, Nazi homophobia was predictably on the rise. Party orthodoxy declared homosexuality a “non-Aryan” indulgence. Nazi thugs protested gay films and attacked their creators. Their National Observer magazine, Bryant reports, claimed in 1929 that Jews were “forever trying to propagandise sexual relationships between siblings, men and animals, and men and men”.

In 1934’s Night of The Long Knives, an attempt by Hitler to wrest control away from the SA and purge the party’s gay members, Rohm and dozens of others were murdered. This proved a watershed for Boothby and Sassoon. “The Nazis had been shown up for what they in fact were – unscrupulous and bloodthirsty gangsters,” Boothby wrote. “In future they should be treated as such.”

Berlin in 1930 was the most liberal place in the world for gay men. And just six years later, gay men were being sent off to concentration camps, tortured and killed

That it took only a few years for German culture to reverse so strikingly has worrying implications, and particularly for countries under extreme stress. “A lot of people think today, that attitudes have changed, and all the freedoms that we've won as gay men in particular in the last 20 years will never be reversed," says Bryant. “But actually Berlin in 1930 was the most liberal place in the world for gay men. And just six years later, gay men were being sent off to concentration camps, tortured and killed.”

Since homophobia was arguably more deeply rooted in Britain than Germany, it makes our historical trajectory away from fascism seem partly fortuitous. Despite its victory in First World War, Britain’s economy and social structure likewise hung by a thread, and fascist ideologies were influential in the highest corridors of power and press barony.

The Times even declared the Long Knives atrocity an effective “cleaning up” and The Daily Mail praised “Herr Hitler” for having “saved his country”.

Oswald Mosley, the British fascist politician, had been disgusted with Berlin’s permissiveness for years. His blackshirt movement was lauded earlier in 1934 by Lord Rothermere, the owner of The Daily Mail, some of whose employees would grow a periodic fondness for attending work in blackshirt uniform. Perhaps it’s not surprising that Rothermere had attended Nazi rallies on Hitler’s personal invitation.

Jack Macnamara took longer to wake up to the Nazi threat. He was in Germany as the first British politician to visit the Rhineland, a corridor that had been demilitarised via the Treaty of Versailles, but which by 1936 was rapidly rearming under Hitler’s premiership. Macnamara’s German guides showed the MP around their new political innovation, the concentration camp at Dachau, which housed members of “undesirable” races, political prisoners, queer people, and others.

“I have never seen human beings so cowed,” Macnamara wrote.

For other glamour boys, their turn against Nazism was more personal. Harold Nicholson’s friend, Kurt Wagenseil, was under detention in Dachau for “promoting” homosexuality: a charge that pushed Nicholson to pay a personal visit to the German Embassy and demand a meeting. Victor Cazalet pulled considerable strings to ensure the escape of a friend’s Jewish gay partner to Palestine, and soon after began petitioning the Foreign Ministry for greater scrutiny of Hitler’s territorial ambition.

Oddly, though, Cazalet’s string-pulling heroism was something that, until Bryant dug through the archives, had been overlooked. A Cazalet biography written in the 1970s, extracted from the same exchange of letters, omitted crucial detail – a probable sign of Britain’s long hangover of homophobia.

“Most of them didn't have sons and daughters to carry the flame,” Bryant told The Independent. “... And sometimes families were just embarrassed, I guess. Macnamara's brother refused to inherit from him because he was gay. And Barbara Cartland, I'm told, destroyed all her brother's private papers.

“Interestingly, when she wrote a little biography of him, she included a very nice obituary that had been written about him. She carried every single sentence of it, apart from one that referred to him looking 'flamboyant' in the House of Commons. These men got edited out of history. And their sexuality got edited out of their involvement in that history.”

The Nazis’ campaign of hatred was only just beginning. Queer men were tagged with pink triangles, many murdered, and thousands of others – one estimate claims 15,000 between 1933 and 1945 – detained in concentration camps. Plus, given Hitler’s increasingly bellicose rhetoric and militarising moves in the Rhineland, it was clear that the Third Reich would not remain within German borders for long.

Westminster homophobia isn’t something that’s gone away, either. 'The Glamour Boys’ author Bryant – one of the Commons’ few gay MPs – has had his fair share

With its policy of appeasement, though, Chamberlain’s government was dithering. The Spanish Civil War was another watershed. Often called a dress rehearsal for the Second World War, the government was officially neutral between the left-leaning Republicans and Nazi-backed fascist forces, yet the latter received frequent and explicit endorsements by many Tory MPs.

Macnamara could hardly believe his ears, and not least when his attempts to rescue orphaned Spanish children were initially blocked on account of Britain’s apparently ‘unsuitable’ climate.

Change was afoot. For Boothby, Macnamara, Nicolson, Cazalet, Cartland, Sassoon, and others, the threat was clear. “How true and how right were our conclusions,” Bootbhy wrote retrospectively. “Alas! In other quarters, a different view was taken.”

The group joined forces with two other opponents of appeasement, Winston Churchill and Antony Eden, who’d just resigned as Chamberlain’s Foreign Secretary: a move that landed him accusations of mental incapacity in the House of Commons by his own Prime Minister. They began secret meetings at group members’ houses, and sought to keep things largely discreet. But this wasn’t always easy.

For one thing, being that their meetings were held close to the Commons, the to-and-fro was sometimes easy to detect – and especially when Jim Thomas’ house (another group member) was right next door to a staunch Chamberlain ally. Another problem was Boothby’s motor mouth. One Chamberlain loyalist would catch on, writing that “the H of C is humming with intrigue” and that “the so-called ‘Insurgents’ are rushing about, very over-excited.”

Their biggest threat came from Chamberlain, who tasked his chief political operator, Sir Joseph Ball, with keeping stock and sabotage. A former barrister and intelligence agent, Ball first named the new anti-Appeasers “the insurgents”, but “the glamour boys” emerged as the favoured label. The meaning was obvious. It denoted vanity, a fondness for glitter, questionable masculinity: tropes all synonymous with gay stereotypes.

The press machine got to work. The Daily Mail’s gossip column wrote of a new parliamentary spectre, the glamour boys, which contained “seven or eight youngish members of Parliament, nearly all of them good-looking... viewed with some suspicion by the party heads”.

One MP commented that the glamour boys had an unsolicited appetite for crème de menthe. This didn’t come out of nowhere, either. Ball was no doubt aware of the boys’ sexual lives, since he kept dossiers on dozens of MPs and used networks of spies to gather gossip.

While only one-quarter of the group was queer, those MPs “put the glamour in the glamour boys”, Bryant writes, “and thereby gave their powerful political opponents a stick with which to beat the whole of the group. It is remarkable that this never stopped Eden and Churchill from associating with them, but they were the closest-knit group within the wider alliance and without them the wider group would never have succeeded.”

Ball even went as far as tapping the boys’ phones. Ronnie Tree, a queer group member, wasn’t too surprised. He’d heard a strange clicking on the receiver for some time. Robert Bernays was later told that continued activism against appeasement may entail “personal difficulties”.

The glamour boys weren’t dissuaded, though. As well as risking the destruction of their personal lives – including time in prison and hard labour – their opposition to appeasement held all the signs of career self-sabotage. Simply put, the Conservative Party at the time exercised exceptional loyalty to Chamberlain’s leadership. So loyal were most MPs, in fact, that one glamour boy grew concerned about an emerging tendency towards dictatorship.

Westminster homophobia isn’t something that’s gone away, either. The Glamour Boys author Bryant – one of the Commons’ few gay MPs – has had his fair share. “Sometimes [it was] from other MPs. David Cameron, for example. And interestingly, a Conservative MP was telling me the other day that he had hung his own head in shame when his party was attacking me on the basis of my sexuality.

“In the early days, certainly from the press, [too]. And I was attacked at one point for taking part in a debate about education because I was told I would never have children of my own, being a notorious homosexual.” The problems persist more broadly, too. An analysis by The Guardian from 2019 revealed that hate crimes against the LGBT community had more than doubled since 2014, supplementing the state-endorsed homophobia seen in Russia, countries in Eastern Europe, and parts of the Middle East.

For the group, a vocal opposition to anti-Semitism also brought a layer of risk. Despite its later battle against Nazism, Britain was home to an endemic anti-Semitism that had lasted and festered for centuries.

The right-wing press especially was fond of running hate pieces and vitriol, including serialisations of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and “scientific” analysis of Jewish facial structures. Edward Doran, a Tory MP, urged the government to contain the “scurrying” tide of “alien Jews”, and Nancy Astor – a parliamentarian lauded by Theresa May and commemorated in a Westminster statue – made frequent jabs at Jewish politicians, with one particular comment irking Churchill enough to call her “that bitch”.

Again, the glamour boys were not dissuaded. In 1937, Cazalet and Macnamara founded a cross-party Commons group to investigate Eastern European anti-Semitism, and in September that year Philip Sassoon’s house was daubed with an enormous “Perish Judah” slogan. Bernays, one of the more vocal anti-fascist boys, had his election posters vandalised. “I am not, of course, a Jew,” he responded, “but even if I were, what would it matter? These stupid tactics leave me quite cold.”

Most shockingly, much of the press’s anti-Semitism was directed by Chamberlain and Ball personally from 10 Downing Street. To consolidate their media influence, Ball purchased a popular magazine, Truth, and staffed it with mouthpiece journalists at the government’s beck and call.

“Jews debauch the minds and standards of a community,” Truth wrote, alleging that a secret Jewish cabal was controlling The Daily Mirror. If anti-Semitism escalated in Britain, it would be the “Jews own fault: it’s no exaggeration to say that of every 10 swindles that come under the notice of Truth, an unduly high proportion are operated by Jews”.

Chamberlain’s sinister role in The Glamour Boys may come as a surprise to its readers. While hardly celebrated, in our popular history Chamberlain is more often an agent of impotence and poor leadership than outright darkness: a quirk that Bryant has sought to revise. “I think Chamberlain was a pretty disreputable figure,” the MP told The Independent.

Churchill’s appeasement had its first major test in 1938. Having tolerated German intervention in the Spanish Civil War – including the commission of war crimes – and large-scale remilitarisation, Chamberlain was stunned when Hitler invaded Austria and declared an annexation. The prime minister stuck to his guns – or lack thereof – and signed the Munich Agreement with Hitler soon after, agreeing to countenance the Nazi occupation of outer Czechoslovakia in exchange for a de-escalation of conflict.

The response in Westminster was tragic and absurd in equal measure. Securing an overwhelming endorsement in the Commons vote, the Agreement found disapproval and abstention among the glamour boys, who declared the paper an “unmitigated disaster”. MPs literally cried in jubilation, and some insiders even called Chamberlain the “reincarnation of St George” and “divinely Christlike in compassionate understanding”. That Chamberlain had apparently “salivated” over suspending parliament to force through appeasement should only add to our retrospective worry.

As we all know, however, the Munich Agreement didn’t last long. Hitler would encroach the Czechoslovakian mainland within months. This development was considered entirely predictable by the glamour boys, and forced the group into a newly energised offensive. They gained allies among the Tories’ senior MPs, secured the backing of its former military members, and drafted a threefold Commons resolution: conscription, a national effort to meet present dangers, and a new National Unity Government.

Macnamara and Ronnie Cartland were swiftly disillusioned by the sheer ill-preparation of Britain’s armed forces. Guns didn’t work. Tanks didn’t roll. Jeeps couldn’t run

So convinced of war’s imminence were two of the boys, in fact, that they signed up to fight. But Macnamara and Ronnie Cartland were swiftly disillusioned by the sheer ill-preparation of Britain’s armed forces. Guns didn’t work. Tanks didn’t roll. Jeeps couldn’t run. And war was due to break out any month.

Chamberlain would soon address the Commons. His speech – a chance for unity in national emergency – neglected to mention Germany, Poland, or Czechoslovakia at all. Chamberlain instead offered his critics a parliamentary recess to regain their "mental faculties".

Cartland, the new military sign-up, was disgusted. Declaring himself “profoundly disturbed” by Chamberlain’s address, Cartland’s speech would meet the full force of Chamberlain’s partisan wing. Yet amid calls to be hanged, kicked out of the party, and expelled from the House, Cartland wrote that “I regret nothing [and] I would say it all again tomorrow”.

Poland was next to fall. Appeasement looked all but finished. When news of war finally emerged, Macnamara and Cartland were already stationed with their regiments. Macnamara had busied himself recruiting new sign-ups for the London Irish Rifles, and was made a commanding officer. The other glamour boys met at Ronnie Tree’s house. Gathered around the housemaid's radio set, the boys heard Chamberlain’s chilling words in the drawing room. “Consequently this country is at war with Germany,” the prime minister declared.

The war’s declaration was a mixed blessing for the boys. While their warnings – some of which had stretched over nearly 10 years – had been utterly validated, the conflict’s flimsy prosecution was nothing if not concerning. Macnamara and Cartland, the two recruits, still reported problems of inadequate material, and Chamberlain’s campaign in Norway proved disastrous. In the campaign’s aftermath, Chamberlain’s arrogant Commons address, and what Bryant calls the resulting “toxic atmosphere”, opened a new political vista for the boys.

But tragedy was just around the corner. While defending a road to Dunkirk in 1940, Cartland was shot and killed. His death stunned Churchill. He was “so brilliant and splendid a son, whose exceptional abilities would have carried him far”, he wrote to Cartland’s mother.

Death would stalk boys further still. While on tour in the Middle East in 1943 – during which he made further calls for a Jewish state and allied with senior Zionist leaders – Cazalet died in a plane crash, rumoured to be an act of Russian sabotage. Macnamara, the second recruit, died in a German mortar explosion in 1944. And Bernays, the fearless campaigner of anti-fascism, perished in a botched crash-landing the following month.

On the war’s conclusion, a commemorative service was held at St Margaret’s Church in Westminster. Twenty-one MPs had died in the war, including four glamour boys, and their names were emblazoned on wreathed shields on the Speaker’s back wall on Churchill’s orders. The deaths haunted him. Cartland was “a man of noble spirit, who followed his convictions without thought of personal advancement”, Churchill said, and Cazalet someone for whom he “cherished such warm feelings of friendship”.

While long-deemed a national hero, Churchill’s legacy is more disputed than ever. That his role in ending appeasement was more collaborative than single-minded may complicate matters further. “Churchill got to write the history. And in Churchill's version of history, the hero is Churchill,” Bryant says.

“I don't like putting people on pedestals too much because it always ends up being exaggerated. But, for instance, Jack Macnamara, who was probably, of all the men that I've written about, the most openly 'naughty': Churchill wrote when he died, 'he was all that man should be.' And Churchill almost certainly knew that he was gay.”

“Rather than diminish Churchill, [the glamour boys] enhances him as a great man.”

Bryant hopes that The Glamour Boys will change our national understanding. That Bryant himself, the author of numerous political histories, had no idea of their story – let alone most MPs, among whom he estimates only a “tiny handful” will know the full LGBT picture – shows the editing effect of homophobia, historical revision, and family shame, even in light of laudable personal courage.

“Originally, I thought I would have to write it as a fiction because there wouldn't be many facts out there… or any private papers, because obviously that would have been dangerous. You couldn't write a letter to another man in those days without fearing prosecution and imprisonment. But in fact, I ended up finding a lot of information. Families are being very helpful.”

Macnamara, Cazalet, Cartland and Bernays have been on the Commons wall for 75 years. At long last, their role is being recognised – and especially by MPs on the same green benches: “I mean, everybody goes, ‘Gosh, I'm amazed I've never heard that story before’,” Bryant says.

“There was a perception that gay men couldn't catch a ball, couldn't hold a gun, couldn't throw,” he tells The Independent. “But actually, these people, these men, showed phenomenal bravery and courage.” Who knows where we’d be without them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments